The Sinner: How The Series Lost Its Way

Fans of "The Sinner" just got the worst news. The anthology series ended with the recently released fourth season, and while USA's shift away from premium scripted series was the nail in the show's coffin (per Deadline), the series had been limping through its penultimate and final installment well before its death. All four seasons of "The Sinner" are filled with brilliant performances and stunning cinematography. Still, the compelling and layered narratives of Seasons 1 and 2 gave way to — and further highlighted the flaws in — a confused and meandering storyline in Season 3 and a tired and trope-driven ghost story in Season 4.

When "The Sinner" debuted in 2017, executive producer Jessica Biel's dark horse of a whydunit — based on Petra Hammesfahr's novel and starring Bill Pullman as the central mystery's flawed but dogged sleuth — became the most-watched new cable series of that year (per Variety), and earned Biel an Emmy nomination for her alternately gutting and restrained performance. Season 2 had much to live up to, and as its series high 97% critical score on Rotten Tomatoes suggests, it met and exceeded expectations. Vulture's Jen Chaney called the sophomore return "instantly addictive," adding that "one of the greatest strengths of this season is its confidence in the compelling nature of the story itself to carry the day."

The observation is as accurate for Season 1 as it is for Season 2. Unfortunately, "the story itself" takes a backseat in Season 3, and in Season 4, it fails to live up to the series' premise and promise.

Season 1's true reveal is its exposure of our species

Season 1 ("Cora") offers a fresh twist on the detective-vs-killer exercise in psychology. We assume Jessica Biel's Cora suffered some trauma at the hands of her victim Frankie (Eric Todd), but the reveal isn't your typical abuse or assault story. Not only does it explore the consequences and mechanics of living with PTSD — a disorder film and television rarely depict in anyone but soldiers — it forces us to face some ugly truths about humanity.

Season 1's devastation comes not from bad, evil men doing bad, evil things but from otherwise good men who — when their well-being and comfortable way of life is threatened — decide that Cora's health, sanity, and (ultimately) her freedom aren't worth as much as their own. It's a story that dissolves the comforting myth of the supernaturally "Evil" perpetrator. It reminds us that polite society is forever willing to sacrifice those it deems "less than" if it means staying in control. What's more, the pay-off is worth the wait and no less shocking for the seamlessness with which the puzzle pieces fit together. The rug is pulled out from under us, and we're left to think about where the sin of complicity (Frankie's sin) falls on our list of secular commandments.

Season 2 ("Julian") engages the viewer in similar, even more complicated, ways. There are no true villains (not even Jack Novak, who is the absolute worst character on "The Sinner") in the series' second installment, and the complexity of its mystery combined with its nuanced reflections on big ideas make it the series' best chapter.

Season 2 asks us to rethink the L word

There's no obvious (assumed) explanation for one of the most disturbing parts of "The Sinner" Season 2; Julian's (Elisha Henig) murder of two innocent people. And as the story unfolds and we get to know his "mother," Vera (Carrie Coon), we're also forced to question our assumptions about "people who join cults." Early on, it becomes clear that under Vera's leadership, Mosswood is far from the straightforwardly nefarious, often deadly high-control communities we imagine. The outside world doesn't have the space and time to deal with past trauma (as Season 1 reveals), so the members of Mosswood seek to create one (with varying degrees of success).

In the end, Julian's tragedy isn't the tragedy of a cult survivor but of a child rejected by his father (who, like our Season 1 antagonists, sacrifices others to save himself) and is unwittingly torn between two mothers. And much like Solomon, we find we have sympathy for both. (Season 2's Biblical undercurrent may not be as apparent as Season 1's, but it is there). Julian's story forces us to look at the uglier elements of love, exploring it as an emotion-driven by selfishness, loneliness, and the need to possess. We see it in both of Julian's mothers, in Jack's lecherous assault, and in Heather's (Natalie Paul) inability to put Marin's (Hannah Gross) needs as a friend before her feelings of attraction.

Heather also brings balance to Ambrose (Bill Pullman). Since we've already seen him fill one side of the "push-pull" in Season 1, giving him a worthy partner allows his personal story more room.

Season 3 tackles one too many concepts

Unfortunately, and to the detriment of their story, Seasons 3 and 4 make too much room for Ambrose. Bill Pullman gives brilliant performances in both, but without a worthy narrative to ground his turmoil, it feels like repetitive filler.

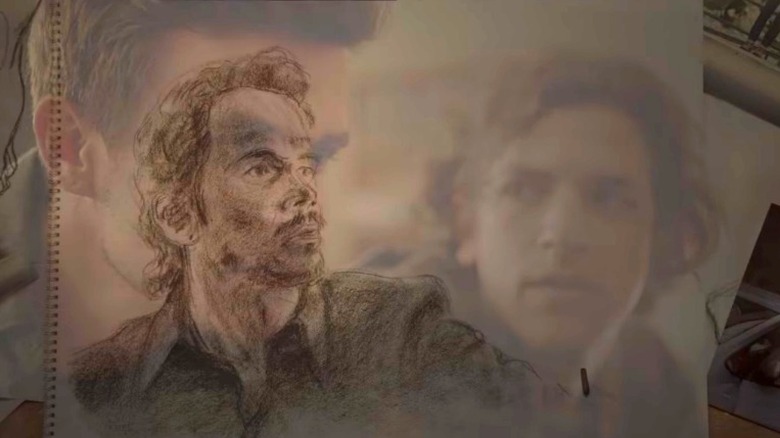

Season 3 of "The Sinner," like 2002's "Murder by Numbers" before it, is a reimagining of the case of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, with Ambrose filling in for the notoriously shabby but skilled Clarence Darrow and Matt Bomer's Jamie serving as the more sympathetic Leopold. Given the series' established concern with motive, the inspiration isn't all that surprising. But Darrow's lengthy closing argument in the trial took twelve hours to deliver (per Chicago Sun Times) and still couldn't fully explain the boys' actions. And yet, "The Sinner" Season 3 attempts to do just that, all while biting off more than it can chew.

Not only does Season 3 attempt to explore and, as Film Inquiry's Reyzando Nawara points out, "[articulate] male vulnerability," it also delves into (in no apparent order of importance and with wildly inconsistent focus and effect): the privileged classes' increasing struggle with depression (per APA), arrested development, a litany of jumbled philosophies, including Nietzsche's Übermensch, Kierkegaard's theology, Jung's "shadow self" (a concept already explored in Season 2), the meaning of life, and, repeatedly, the call of the void, or "l'appel du vide."

Jamie Burns is no Julian Walker

The series misrepresents the last of these, ignoring its reality as a passing, biologically-driven impulse and playing it up as romanticized suicidal ideation instead. This is important because it further speaks to Jamie's (and Leopold's and Loeb's) reductive and confused understanding of these ideas. Still, the distinction is buried under so many other concepts that it becomes difficult to distinguish the series' reality from Jamie's.

Because the series needs us to know that it doesn't support Jamie and Nick's (Chris Messina) understanding of Nietzsche, we're given several lengthy scenes of Jamie waxing philosophical while delivering the same Holden Caulfield-meets-Ted Kaczynski sermon over and over again. We may relate to Jamie's loneliness, sorrow, longing for meaning, and rejection of artifice. Still, this white, privileged, highly educated male's firm belief that the rest of us (well, everyone but Ambrose) don't relate to those things isn't just juvenile; it's insulting, which is curious because we don't need another reason not to like him. What we need, and what the season lacks, is a story. In the end, we don't understand Jamie's actions more than he understands basic philosophical concepts.

Despite its muddled thesis and barely there tension, Season 3 manages to explore some relevant and fascinating themes. Sadly, the same cannot be said for Season 4. In the series' most recent installment, the central investigation is over before it begins. Our sinner Percy (Alice Kremelberg) exists in the flesh for just a few minutes, after which she dies and is relegated to the land of other people's flashbacks and conjured conversations with Ambrose.

Season 4: The road to hell

Ghost Percy acts as our intrepid male detective's conscience, consoler, cheerleader, and sounding board, all embodied in the form of a tragic and lovely young white woman who lives in his head. In short, she's the proverbial Dead Girl, an archetype the season attempts desperately to atone for even as it insists it can be elevated ("... not all Dead Girl narratives ..." it tries, and fails, to argue).

In "Dead Girls: Essays on Surviving an American Obsession," Alice Bolin explores the trope and our love for it. Season 4 goes all in on Bolin's theory of the Dead Girl, but with a handful of tweaks and an uneven veneer of self-awareness that unintentionally makes its enthusiastic use of the device ironic.

For instance, Percy dies by suicide and not murder, and her grandmother Meg Muldoon (Frances Fisher) is the actual (traditionally untrustworthy) patriarch of the Muldoon family. What's more, Percy points out that she exists solely in Ambrose's head (in an attempt to call out the trope without having to sacrifice its catalytic efficiency), and her murder of Donald Heng's Bo Lam gestures toward exposing an ugly reality of the (traditionally white) Dead Girl. That is, as Bolin writes, "Dead Girls help us work out our complicated feelings about the privileged status of white women in our culture ... The white girl becomes the highest sacrifice, the virgin martyr, particularly to that most unholy idol of narrative" (21-22).

Of course, the series spends most of its time asking us to love and have sympathy for Percy so that by the time we learn she "accidentally" killed Bo and "had to" help her family cover up the smuggling of faceless and nameless immigrants, the gesture is as useless as it is gutless.

... is paved with paradox and low stakes

The fact that this dead white girl is aware of her invisibility in death doesn't make her more alive, and her awareness of (and guilt over) her privilege in life doesn't excuse or negate her complicity. That the series posits itself as a "different kind" of Dead Girl story can't save it from the device's inherent implications or the season's boring and tangled storyline.

Since Percy is dead from the get, Ambrose has no sinner to save, and since his superfluous investigation literally can't help her, it's a puzzle he takes on wholly for himself. The stakes couldn't be any lower, a reality Season 4 tries to work around by tying the story in so many knots and injecting so many twists and turns that by the time the whole story comes to light, it's impossible to trust. The writers knew the plot would prove exhausting because it ends on an expositional exchange that wouldn't pass muster in a police procedural.

"Do you understand it all now?" Ambrose's imaginary Percy asks him before adding (in case we're unclear), "... why I jumped?" (at which point, Ambrose proceeds to recap everything we've just watched — out loud and to himself).

Finally, unless one truly believes that suicide is a "sin" on par with murder, the show spends most of its season without a sin to vindicate. Until it's revealed that Percy killed someone, Season 4's premise fails to live up to the series title — and to what made Seasons 1 and 2 of "The Sinner" so compelling in the first place.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

The Sinner turned away from us

For reasons ranging from the admirable (we want to believe humans are good) to the borderline narcissistic (we want to be assured that we could never do such a thing), we're obsessed with motive as viewers. And, as the popularity of serial killer stories suggests, we're far more interested in the killer than the victim. Seasons 1 and 2 of "The Sinner" acknowledged this in an interactive and reflective way.

With each revelation in the first two seasons, we're forced to think about what it would take to sympathize with the killer. We're asked how much you need to agree that this murder is morally "okay?" It's a question that reveals as much about the viewer as the story, and in both seasons, we're given a "sinner" who is ultimately redeemed. In Seasons 3 and 4, our sinners are complex, flawed, and layered but ultimately fully responsible. The series knows this, and instead of focusing on how its story might carry and punctuate the mystery and redemption of the seasons' central sin-tagonists, it relies on a distracting pile of concepts, ineffectual twists, and Ambrose's inner turmoil instead.

Narratively and thematically speaking, the last two seasons ask no more of the viewer than an episode of Forensic Files and less than an episode of "Law & Order." In relief of the consistently interactive first two seasons, it feels a bit like the series abandoned us. And it's this, along with the latter two seasons' failure to add anything new to the genre or construct a compelling story, that sent "The Sinner" down a path from which, like Percy and Jamie, there is no redemption.