I Love You, You Hate Me: The Craziest Things We Learned From The Barney Docuseries

What comes to mind when you think of "Barney & Friends," the hit PBS kids show from the early 1990s? Does your brain populate with images of a friendly purple dinosaur? Do you immediately get an earworm, singing one of the show's gentle songs? Do you remember some of the series' most famous celebrities, like Selena Gomez and Demi Lovato, who started their careers on the show?

No matter the answer, one thing is clear: When you think of Barney and his associated series, themes of love and positivity are likely at the center of whatever you remember. You probably don't think of lawsuits, scandals, and death threats. But for the cast and crew who developed Barney into a preschool phenomenon, troubling situations and disturbing incidents became directly connected to their experiences on the other side of the camera.

Peacock's new two-episode docuseries, "I Love You, You Hate Me," examines the dark side of this beloved children's franchise. Though you might scoff at the mere idea of a gritty Barney docuseries, "I Love You, You Hate Me" more than proves its worth before Episode 2 is over: There are many shadowy depths to plumb in the world of the docile dinosaur. The series contains multiple moments that are downright disturbing, which contrasts creepily with the smiley façade Barney still maintains. Here are the craziest things we learned from watching "I Love You, You Hate Me."

Barney almost wasn't a dinosaur

If you grew up watching "Barney & Friends," you may recall that it doesn't ever portray Barney as a real entity. As his theme song puts it, "Barney is a dinosaur from our imagination." Each episode shows kids seemingly bringing Barney, an inanimate dinosaur plush toy, to life in their heads.

Even though actual dinosaurs don't match Barney's friendly demeanor, it's hard to imagine the character as anything but a prehistoric pal. However, "I Love You, You Hate Me" reveals that a few other ideas were on the table before Barney was finalized as a dinosaur. Pat Reeder, the original head writer of Barney's first incarnation, developed scripts from the crew's treatments. "The original treatments that I saw, they were very rough. It wasn't even Barney the dinosaur yet," Reeder says. "If I recall, they had different toys coming to life. One was a bear, I think. One was a clown doll. I didn't want to do the clown doll."

In an archived clip, creator Sheryl Leach confirms Reeder's recollection that Barney was initially a teddy bear. Leach goes on to say that when the Traveling Dinosaurs exhibit came to her hometown, her young son suggested she change Barney into a dinosaur.

One of Barney's performers is now a tantric energy healer

While Bob West voiced Barney, David Joyner was his physical performer, operating inside the purple dinosaur costume for about a decade. You may have heard rumors about Joyner over the years, perhaps even on the playground from kids looking to blow their peers' minds. In "I Love You, You Hate Me," the actor shares his side of the story.

After he moved on from Barney, Joyner continued acting here and there, but his true passion was in something known as tantric energy healing. This interest was something Joyner's Barney contract directly prohibited him from pursuing during his run on the show. What is tantric energy healing, exactly? Joyner describes it this way: "As a tantric energy healer, I help goddesses reconnect with their sexual energy on a spirtual level." He continues, "You study white lotus tantra, you learn sexual energy is not for physical gratification. It's for spiritual elevation. The fees for my services are basically for the energy work and the massage and the meditation. Anything beyond that, there's no extra fee." An offscreen documentarian then directly asks Joyner if he has sex with his clients, to which Joyner replies, "Not necessarily. Not all the clients have a full session, with what you consider sex, but in tantra, we consider it spiritual intimacy."

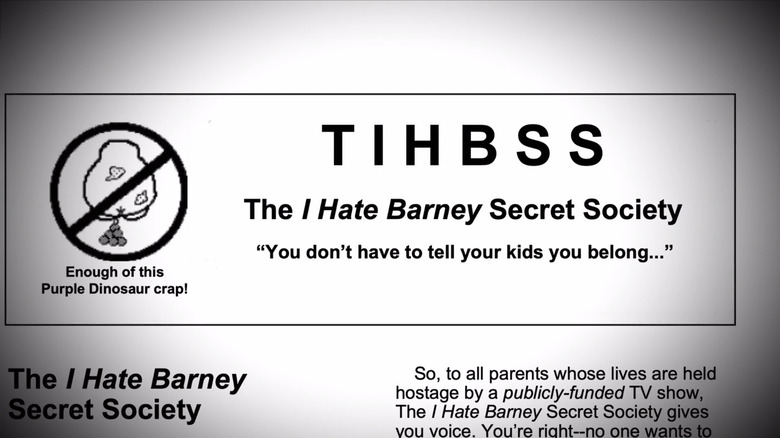

An angry dad created a newsletter to cope with Barney overload

Much of the runaway success of "Barney & Friends" came from the fact that the program understands its preschool audience. It doesn't try to be a children's show that also appeals to parents on a secondary level — it goes all-in on its target demographic. That means lots of repetition, an abundance of positivity, and a collection of songs designed to engage kids as active participants, not just passive viewers. For preschoolers, it's heaven. For some parents, it's torture.

Robert Curran, whose daughter was Barney-obsessed in the early '90s, took action. "Parents couldn't share Barney with their kids," Curran says in the docuseries. "Barney just drove all the parents crazy. I realized I had to do something." Curran created the "I Hate Barney Secret Society," a newsletter that frustrated parents could subscribe to for 50 cents. Upon launching, Curran received 7,000 subscribers in just six weeks.

Inspired by his previous experience with Alcoholics Anonymous, Curran approached the treatment of Barney fans with techniques similar to the ones people use when recovering from substance addiction. In an age before access to anything like social media, parents felt seen by Curran's project. "With the 'I Hate Barney Secret Society,'" Curran says, "I just gave voice to all the fears of all the parents who were having problems with Barney."

College students hosted Barney bashing parties

The more layers that "I Love You, You Hate Me" unearths, the more the viewer realizes this story is about much more than Barney. It speaks to the core of outrage culture and the dark relationship many adults have with their childhood.

Seemingly angry that Barney took the place in kids' pop culture that was once held by characters of their own youth, college students of the early '90s held parties where attendees hit, smashed, and otherwise destroyed Barney dolls. "Barney bashing," as it came to be called, was originated by Travis Fox at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 1993. "I was born in 1970, so my character was Big Bird," Fox says in the docuseries. "I think the reason that we specifically went after Barney was he was the replacement to our 'Sesame Street.' He was encroaching on our childhood, so we decided that we would kind of push back." Among the activities involved in Barney bashing were hitting a Barney piñata, and watching a brawl between people wearing knock-off costumes of Barney and Big Bird.

Barney bashing is yet another reminder of the strange dichotomy of Barney existing as an emblem of peace within his own series and Barney inspiring multiple hate movements in the real world. The contrast between these understandings of Barney could be a focus of the "Barney" movie in the works from producer Daniel Kaluuya, though it's unlikely that Barney bashing itself will have anything to do with the story.

Barney's music producer received death threats

"Hate-watching" is a common enough practice to deserve its own name. There's a line, though, between hate-watching and the dangerous territory Barney hate often crossed into. Disapprovingly consuming content for the sake of discourse might be petty, but at least it has the opportunity to remain civil. Negativity surrounding Barney often went far beyond simple criticism into straightforwardly disturbing incidents.

Bob Singleton was the music director on "Barney & Friends." In the docuseries, Singleton discusses how some adults' hatred of Barney went too far and affected him personally. "I was nominated for a Grammy and I was interviewed by a local radio station. The phone calls came in, and there were people saying, 'His music drives me crazy. Man, I'd just love to get my fingers around that's guy's neck.' I was surprised that they felt like they wanted to do me physical harm."

This response wasn't just annoying — it was scary. "I was in fear," Singleton recalls. "I got actual death and dismemberment-of-my-family emails." This was something much deeper and darker than destroying plush toys or writing annoyed letters: The safety and well-being of people involved with Barney was put in question, all because some grown-ups found the songs a little irritating.

Barney was made for its creator's son

Sheryl Leach created Barney to entertain her then-toddler son, Patrick. The longer that Barney's programs aired and the bigger the franchise became, the more Leach's family faced troubling circumstances. The docuseries stops short of coming right out and saying it, but it heavily encourages the viewer to ponder the juxtaposition of Barney's rise to fame with the hardships of the Leach family.

The more success Barney enjoyed, the more involved Sheryl Leach became in keeping the business afloat creatively. This seemingly putting a strain on her marriage. She and her husband separated, and he eventually died by suicide. Furthermore, while Barney was created for Patrick Leach, he resented Barney as he got older. This was not simply because of Barney's preschool-oriented nature, but because of the way the character captured so much of his mom's attention. In adulthood, Patrick Leach attempted to murder his neighbor and served jail time for his actions.

The documentary presents this information and lets the viewer decide what to make of it. While it never directly ascribes Barney's creation to Patrick Leach's attempted crime, the series does ask the viewer to consider the effects a mega-franchise might have on a child whose parent is in the thick of its success.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

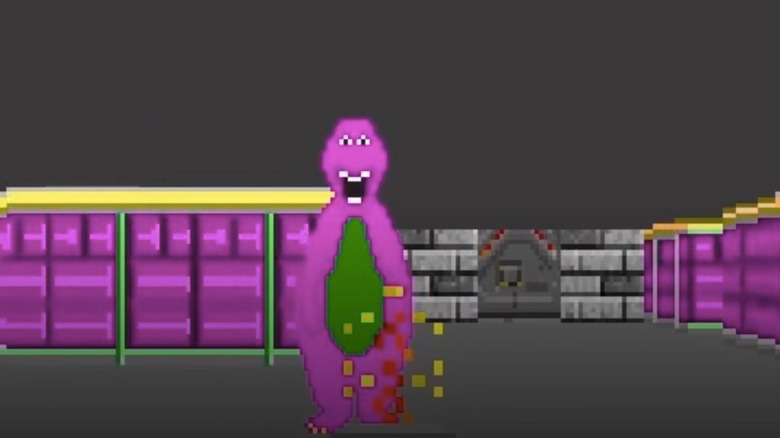

Destroying Barney online

Barney's meteoric rise to fame and the hate movement it spawned happened to align with the advent of the World Wide Web. One of the first 15,000 web pages ever created was dedicated to giving people an outlet to channel their Barney anger into outright killing the big purple dinosaur. It was called "The Jihad to Destroy Barney," and it's probably still one of the creepiest video games ever made.

While he didn't create the web page, a man named Sean Breen came to enjoy the game and eventually became its last leader. In the docuseries, he says, "'The Jihad to Destroy Barney the Purple Dinosaur' is a collaborative roleplay session where we were super-soldiers fighting a shadow war against Barney the dinosaur." Breen continues, "Our criticism of 'Barney' was that it was all about conformity and consensus, and that's absolutely a very '90s attitude. On the Internet, we were all rebels fighting against the stifling conformity of the normies." He seems to say that last part half-jokingly.

The game's guide elaborates on the players' opinion of Barney: "The hell worm Barney, the jihad's primary adversary, the top villain, the great demon, sits on a throne of skulls. Some call him a minion of Satan. Barney must be destroyed. All else is irrelevant."

The voice of Barney brought two other kid-favorite characters to life

Throughout the collective 22-year run of "Barney and the Backyard Gang" and "Barney & Friends," two actors voiced the titular character, splitting their work around the halfway mark of the franchise. Bob West voiced Barney from 1988 to 2000. While families with young kids in the '90s might not have realized it, they heard West's voice in another popular children's production that blew up around the same time: A pizza-arcade-playground fever dream owned by a certain Charles Entertainment Cheese.

West lent his talents to Chuck E. Cheese establishments as the voice of two robotic figures who perform concerts for birthday party attendees: Jasper T. Jowls, the banjo-playing dog, and Pasquale, the pizza-maker. If parents took their kids to Chuck E. Cheese to get out of the house and enjoy a break from constantly playing "Barney" tapes, it's quite possible that West inhabited their entire day, albeit anonymously.

West certainly didn't expect voicing Barney to define his career. "Getting the role of the voice of Barney, it started out as just another audition," he shares in the docuseries. "It was 1988, and I came up with a voice just right off the top of my head." The rest is history.

Barney sued the San Diego Chicken

The San Diego Chicken is a popular mascot character who has amused attendees of sporting events for decades with his humorous antics. In the '90s, though, the mischievous bird had a lawsuit on his hands — er, wings. Around the same time as many other hate-driven Barney movements swept the nation, the San Diego Chicken introduced a bit into his sideline schtick where he tackled another mascot meant to look like Barney. Naturally, the crowd cheered. The Chicken continued performing the bit for nearly two years without any pushback.

Sheryl Leach, Barney's creator, had ignored other instances of Barney hate up until this moment. But the San Diego Chicken proved to be a tipping point. The Barney team sued the Chicken, citing that there had been no authorization to include the Barney-esque character in the bit, which was seen by hundreds of thousands of people. But Barney's crew lost the lawsuit, due to the intricacies of parody law. The Chicken's inclusion of Barney had always been to make fun of the character, not to imply that its version was the official Barney, or communicate on behalf of Barney's owners. On those grounds, the Chicken won.

Barney kids were bullied

While Barney and his dinosaur pals Baby Bop and BJ are prominent throughout "Barney & Friends," most of the show's cast members are child actors portraying the kids who play with Barney each day after school. After the show's first few seasons, the initial group of child actors aged out of their roles, departed, and were replaced by other kids.

As the first round of actors tried to return to normal life as teenagers, bullies at their schools made it difficult to do so. Pia Hamilton, who played Min, reflects, "I remember feeling excited to go back. I just wanted to be a normal kid, do all the normal things like everyone else was." Leah Montes, who played Luci, affirms this sentiment, saying, "I was excited to get to go back with my friends that I'd had forever and also have this Barney experience with me, but it was not well received."

"There was always those people that were kind of the Barney haters," Hamilton recalls. Hope Cervantes, who played Tosha, agrees, saying, "Kids would call me Barney lover and they would come up to me and say Barney must have molested us or something. I'd get that all the time. It really was painful given my history of actually going through that. It stung." Some kids may have loved Barney, but many didn't love those who palled around with him.

Barney was marketed by moms

While Barney eventually came to be a major franchise belonging to a large media company, the character's beginnings were homegrown. He was built from the ground up by creator Sheryl Leach and her small team. At the time, "Barney and the Backyard Gang" was nothing more than a handful of low-budget adventures sold on videotape. Without a formal marketing department dedicated to selling Barney videos, a special group of superheroes took to the phones to spread the word: moms.

"In the early days, we didn't have enough money to make the videos and spend money on marketing," Leach says in a 1993 interview included in the docuseries, "so we decided to hire a group of our neighborhood mom friends. We called those moms the 'mom blitzers.'"

Eventually, positive word-of-mouth about Barney caught the attention of two key players in the character's global success. Sloan Coleman's friend recommended she rent a Barney video to entertain her son. Coleman loved it so much that she contacted Leach about marketing the tapes, and ultimately became senior vice president of Barney's live events and stage show productions. Meanwhile, Larry Rifkin, head of programming at Connecticut Public Television, couldn't help but notice his daughter's obsession with Barney videos. Seeing the potential of the show beyond videotapes, he pitched Leach a leap to PBS. This move expanded the show's reach exponentially.