I Love You, You Hate Me Director Tommy Avallone On Adults' Dark Obsession With Their Childhood - Exclusive Interview

This interview contains references to suicidal thoughts.

When most people hear the phrase "Barney the dinosaur," they picture the happy-go-lucky dinosaur that primarily lived on TV screens between the late '80s and early '00s. Yet some people have much darker memories of the purple dinosaur that preached love and acceptance. Adults have this tendency to bash — often literally — content that's not made for them. Other times, they appropriate it in disturbing ways. Tommy Avallone's new Peacock miniseries "I Love You, You Hate Me" dives deep into the concept of adults needing to protect their childhoods by hating on any children's content that comes after.

The documentary covers everything from Barney-bashing events, beating up Barney at baseball games, parental hate groups, and homophobia against the purple dino, to how this seething hatred affected the children (and adults) involved with "Barney" both on and off the screen. Before tackling the seedy underbelly of "Barney," Avallone directed documentaries like "The Bill Murray Stories: Life Lessons Learned from a Mythical Man," "I Am Santa Claus," "Waldo on Weed," and "Community College."

During an exclusive interview with Looper, Avallone dissected the psychology behind the adult hatred of Barney, the evolution of trolling, the cult mentality of fixating on hate, and how this phenomenon spawned into harassment toward young actors like Jake Lloyd, who played young Anakin Skywalker in "Star Wars: Episode I."

The psychology of Barney bashing

This documentary is such a wild ride from start to finish. What personally made you choose this subject?

I saw this video on Instagram. It was an old 1993 news broadcast of a Barney-bashing event [at] the University of Nebraska. All these college kids were beating up Barney. It was an event where they were hitting him with a hammer, and all these dudes with mullets [were] throwing darts and ripping up Barney. At the end, the newscaster was like, "Well, that's the future of our country right there," and it's like, oh my god, we're living in that future right now. Why don't we explore that hate that's going on, but we could tell it through this rise of Barney the dinosaur? "Barney" came out [on] PBS in '92 — [the] early internet [days]. There [are] so [many] things that we can explore about [the] first times we [went] online to collectively bash something.

Did you uncover anything you didn't expect throughout this process?

Totally. I didn't know anything about "Barney." As far as some of the traumatic stuff that happened with the family of the creator and also the way it was created, you would think a character like this [came] from some big shot in New York or Los Angeles. But it was two moms — two school teachers created "Barney." They saw that their children needed something to watch that was educational and could keep their attention, and they did it. They made eight tapes. These are the tapes right here, and then they became so successful [that] PBS put them on TV, and they blew up.

A slew of iconic children's TV hosts

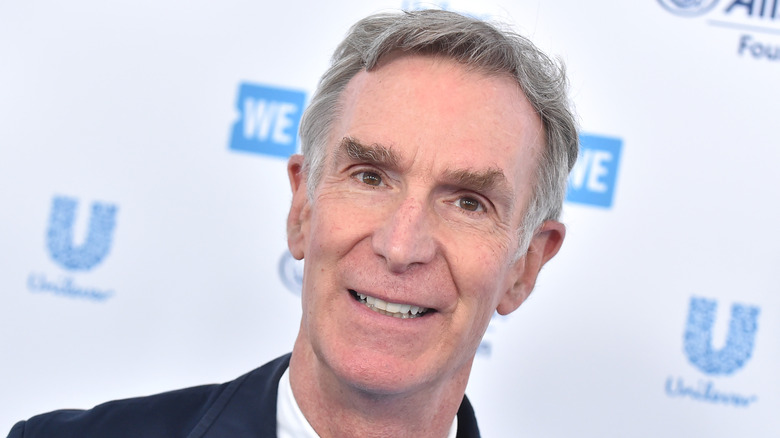

You got some really big names to offer insight, like Bill Nye, Steve Burns, and Al Roker. Did it take any convincing to get quotes from these names, or were they game to jump on right away? Was there anything that you tried to get that you weren't able to?

Yeah. I don't want to say it was difficult, but it was just scheduling. Thankfully, it was friends of a friend, some of the people who have seen some of my other documentaries or someone on their team [had] seen some of my stuff, or I worked with them before. It was a lot of that boring [networking], and it all worked out.

We did try to get Tinky Winky in this. We interviewed him on Zoom, and he was great, but he was in Europe at the time, and it was going to be difficult to get him out.

I'm not sure how young you are, but if you remember Stick Stickly, Stick Stickly was this interstitial thing on Nickelodeon. It was like a Popsicle stick with googly eyes. If you Google it, you'll see. We interviewed Stick Stickly and the voice of Stick Stickly. I've never interviewed a stick before. It was fun to interview him in that. We talked to him about serious stuff like where he come[s] from, and the stick answers, and it's so beautiful. But we interviewed a character that comes with a copyright, so we couldn't use it in there. Yeah, we tried to get a murderers' row of children's programming people.

The OG fandom trolls

Something that really stuck with me is the comparison Gavin Edwards makes between people having this writhing hatred of Barney and the energy people spend going after actors like Jake Lloyd, who played young Anakin in "The Phantom Menace." I think people often dissociate from the fact that behind every one of their favorite or least favorite characters in pop culture, there's a real person. What are your thoughts on this phenomenon and things like harassing actors and review-bombing feminist, LGBTQ+, or diverse shows and films?

We wanted to get a little bit more detail in our talking with them, but I was thankful we at least got to do as much as we did because even with two hours, there's still so much you had to put in there. I find it very interesting how people feel the need to protect their childhood, as if their childhood is all in danger. In doing so, particularly for "Episode I," "Star Wars: The Phantom Menace," Jake Lloyd is maybe eight, a young boy playing Anakin Skywalker. All these "Star Wars" fans from the original movies are bashing the movie, bashing him and Jar Jar Binks. The actor for Jar Jar Binks almost killed himself. But particularly, they're saving their childhood. "You're ruining my childhood, George Lucas." But in doing so, they actually ruined Jake Lloyd's childhood. This kid got bashed nonstop [in] high school [and] college. It's very upsetting to see what happened to him all because he did this movie and [the actions of] "Star Wars" fans.

Going into this documentary, I expected a bit more drama and scandal behind the scenes of the show, but instead, most of the tensest moments come from the public's hatred of this purple dinosaur. Did you go in expecting that, or were you also surprised that there wasn't a bit more scandal?

I'm not an ambulance chaser. I wasn't trying to find that sort of thing. A lot of people talk about the dark side of "Barney" from our trailer, but it's not the dark side of "Barney"; it's the dark side of us. Why [does our] culture need to do these things or feel that we have to do this? "Barney," more or less, played it straight. There [are] some weird characters, and I'm using "weird" as a positive way that worked on "Barney," so there is some stuff there. But here's this character that was created to teach us how to love, and we said, "No, thank you." Why was that? The tagline, love, hugs, and American rage — and that's the American way.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

When people need something to hate

We've had this trend of adults engaging with children's content in the past couple of decades — whether it's adults making videos beating up Barney or people sexualizing cartoons like "My Little Pony." What are your thoughts on this phenomenon, and where do you think people need to draw this line?

I think sometimes people don't realize who is seeing some of the stuff they're doing. When "Barney" came out, I was ten years old, so I was too old for "Barney." Then later in life, [my friends I], I'm thinking early teens, we would make videos. My aunt made a Barney costume for me, and my friend, Timmy, dressed like Mister Rogers and beat me up as Barney. It's a little skit. We thought we were funny. We weren't, but we [tried] to be like Mad TV at the time. Actually, a snippet of it is in the documentary. [In] the very beginning, there's a [clip of] Mister Rogers beating up Barney. That's me. But we did it. It was just to make ourselves laugh and whatever, but once that transcends into, well, who's watching it, like the San Diego Chicken going to these baseball parks?

The San Diego Chicken is a mascot that would beat up Barney as a part of his act for anyone going to see baseball games. The "Barney" people, rightfully so, were like, "You shouldn't be doing that in front of children." I think a lot of times, it's like, okay, my son loves Blippi. Yeah, sure. Do I find Blippi annoying? [Yes.] But I would never openly say anything bad about Blippi in front of my kid because it's something that he loves and adores. And if his dad is then saying it's annoying, then he has to question his love for something.

It's a lot of that stuff. It's okay to find something irritating. It's okay not to like something, but when you openly lead with hate, it's not the best thing possible. Talk about weird characters. We interviewed a former neo-Nazi in this — underline the "former" [of] "former neo-Nazi."

She left that life behind and has now gone and helped people get out of that stuff. She definitely knows where hate comes from. In our documentary, she talks about what you mean. These are weird comparisons, but it's like, why be the person that hates grapefruit? Be the person that loves avocado. Don't define yourself by the things you hate. Be the one that's enlightened by the things that you love. Follow the thing that makes you happy and go that way [as] opposed to going, "I need to break this thing down."

The homophobia tied to Barney-hating

It's interesting that you brought that up because I just had a thought that it's almost like a cult mentality, this [phenomenon of hating Barney. Everyone is] connecting over this one hatred, and it's almost difficult to get out of that mindset because that's one of the singular things that you're focusing on.

Yeah. If there [are] certain things about yourself that you don't like, you form an identity around that thing you hate. Shannon's identity at that time was neo-Nazis, and she was searching for herself, and she thought she could find herself there. Thankfully, she got herself out. In doing so, she sees all these traps [that] people can fall into, like, "Oh, I don't like this, but this person says this is okay. I didn't get this in my life because of this, and I should hate that." It's quite easy to fall into a hate group, but thankfully, she does what she does to get people out of it.

One of the most disturbing parts of the documentary for me was the link between the homophobia against Barney's flamboyancy and the AIDS epidemic that was going on at the time. It seems like more people were engaging in this kind of useless, misplaced hatred than actually doing anything to help an entire population that was suffering. It doesn't seem like we've learned much from it, either. Can you speak on that a little bit?

My production partner for this was Scout Productions, and they win multiple Emmys every year for "Queer Eye" and "Legendary" and the shows like "The Hype" and stuff. Especially with producing "Queer Eye," they identify a lot with exactly what you're saying. Here's this purple dinosaur. Rob Eric, our executive producer ... he was too old for "Barney," but he would hear someone else talk about Barney, like, "Oh, was your kid gay? He likes Barney" ... And Tinky Winky got it the same way because he was purple [and] he had a purse, or he danced in a weird way. People need to attack these characters or attack the people that like them. You look at the T. rex, this scary "Jurassic Park" thing, and now the show softened that and made it smile and purple. For some reason, people get upset about that stuff.

The evolution of adults hating on kids' content

Adults seem to dissociate from the fact that they're attacking children. [They're] putting these labels and saying these things about children. You're not attacking this TV show; you're attacking the kids watching it.

Yeah. I think a lot of people think some of their behavior is harmless. By showing these things that we're putting in this documentary ... They might seem harmless, but let's look at some of the results that actually do happen, so it isn't that. I don't think anyone thinks it when they do it, but when you're old enough for children's programming to not be made for you, there is this element of this fondness for your childhood and knowing that it's gone, meaning that children's programming is no longer made for you. You're too old for that, and there's a sadness there. "It was better when I was a kid." It's [a] reminder that we are getting older and we are so much closer to death.

When we talked to Travis, who did the Barney-bashing event [at] the University of Nebraska, he's like, "My character was Big Bird, and I wanted to protect Big Bird. I don't want some other character coming in and being number one." There is that element of, "Why do you feel the need? Why do you feel that responsibility to protect Big Bird?" I think Big Bird will be fine. But the idea of, "That wasn't my children's character. Now I'm too old." I think there's a lot going on.

How do you think that this concept of hating on children['s] shows and finding things to hate has evolved from the time that this originally happened for this particular show, and how do you think that it seeps into other aspects of life that we deal with today?

You mentioned Gavin Edwards. He's a great journalist. He wrote a bunch of books about Mister Rogers, and he actually has a book about Samuel [L.] Jackson. So different. He talked about [how] when there's a character that seems perfect, it reminds us that we aren't. There is this, for some reason, need to break that down to make these almost fake things, urban legends [about] Mister Rogers, [like], "He had tattoos." "He was a military man." "He shot children." People made things up about him. Steve from "Blues Clues" — "He died of a heroin overdose." "He died of a car crash." Then Barney — "He killed himself in a suit." "He hid drugs in his tail." "Play the song backwards; it's satanic." There are all these urban legends that people make up to somewhat make [themselves] feel better.

What's next?

Have you noticed yourself approaching media, especially children's media, in a different way after doing this documentary?

Totally. My son watches Blippi, and my [two-year-old] daughter's been watching people dress like Anna and Elsa, and then they do these weird things. A part of me is like, "This is weird," but I say to my wife ... we say to ourselves every once in a while, "Don't be a Barney-basher."

Is there anything else that you wanted to touch on with the documentary or upcoming work or how you want to approach this subject in the future? I think I saw another documentary in the works that was Barney-related.

No. That's IMDb being weird. For some reason, they threw our project up in three different ways. [My upcoming] documentary is called "The House From..." It's all about what it's like to live in a famous house from a movie or TV show, so what's it like to live in the "Golden Girls" house, "Friday" house, "Twilight" — all these [famous] houses. We talked to all the people that live there, and we're making this documentary about it.

We have a Kickstarter right now, thehousefrom.com. Barney's the big project. This house project is something a little bit smaller, but it's something we thought was interesting. What's the inside of the "Full House" really look like? What is the inside of "Friday" really look like? I'm not sure if you're a "Friday" fan, but there [are] people who've stuck their head in this woman's window and said, "Break yourself." People throw pizza on the roof [of] the "Breaking Bad" house. People attack "The Goonies" house. It's some crazy stuff that happens.

"I Love You, You Hate Me" is now streaming on Peacock.

This interview has been edited for clarity.