12 Biggest Things That Went Wrong With Lost

"Lost," which debuted in 2004, broke boundaries and redefined the capabilities of broadcast television. Its influence on serialized storytelling is arguably second only to "The Sopranos" in ushering in the "Golden Age of TV." It was often gripping on both a character and plot level and full of unexpected moments that kept fans speculating wildly from week to week.

Yet "Lost" was and remains a frustrating show that never adds up to anything greater than the sum of its parts. Much like Oceanic Flight 815, "Lost" broke apart before pulling off anything close to a landing, as all six seasons turned out to be building to a supremely polarizing finale. It was either an ending you didn't understand or one very far removed from what you really wanted to see. The finale and the choices that showrunners Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse made with "Lost" cast new light on the weaker parts of the earlier seasons, making it clear in many ways how little of a plan they had as they went along. Here are the 12 biggest things that went wrong with "Lost."

The writers were as lost as the characters

"Lost" suffered from its own groundbreaking nature in a certain way. The model of network television has historically let series run as long as viewers are still tuning in, sometimes for decades in instances like "M*A*S*H*" or "Law & Order." The creators of "Lost" originally planned on just three seasons (via Collider), and then found themselves in a strange reverse negotiation with the studio to actually let them plan on ending the show. Until that deal was hashed out, they had to stall for time and add more mystery elements without revealing too much of the endgame too soon. ABC's initial offer was to let the writers end "Lost" after 10 seasons, so it's relatively fortunate Damon Lindelof negotiated them down to six.

As a result, after a propulsive and well-paced first season based on the mystery of what was in the hatch, the middle seasons of "Lost" begin to feel like a small amount of butter spread over a whole loaf of bread. Lindelof in particular took this lesson and applied it to future projects that he kept relatively short and sweet, often to critical acclaim, like the single season of "Watchmen" or the three seasons of "The Leftovers."

The flashbacks

For all the cliffhangers and inexplicable polar bears, the main appeal of "Lost" is its cast of characters. It finds a successful formula right off the bat, with most episodes telling the story of the survivors on the island intercut with flashbacks to one of their pre-crash lives, often with dramatic parallels to what they're facing in the present. It was such a successful formula that "Lost" ran it all the way into the ground over the next few years.

Arguably the flashbacks are all diminishing returns after "Walkabout," where we learn that Locke was formerly paralyzed, but it's indisputable that the narrative device is fully dead by the time we learn Kate used to be married or waste an hour with an outright disastrous episode about what Jack's tattoos mean. Especially as the mystery in the present dragged on without answers, it became fatuous to tell us that Locke used to live in a commune or whatever. The flashbacks never technically stop, but beginning with Season 3's brilliant surprise flash-forwards, they become mercifully less and less frequent.

Endless cliff-hanging

"Lost" apologists say that the show was always more about its dramatis personae than its plot and so shouldn't be judged harshly for all of the holes and unresolved storylines it left behind. But that's denying the basic reality that "Lost" is a cliffhanger-delivery mechanism: nearly every week, some new mysterious element is introduced or explored, and the cut to the ominous title shot at the end of each episode interrupts viewers desperate to see what's about to happen.

Each season finale is perfect evidence of this bad habit. "Lost" isn't structured in a way that makes any season particularly satisfying as a story on its own; instead, each is designed to fold into the next, giving us a trail of cliffhangers like breadcrumbs to follow to the big series finale. What's down the hatch? What's going to happen to the survivors captured by the Others? How did John Locke die? What happened when the bomb went off? If "Lost" wanted to be about character, it wouldn't have made us sit with so many distracting questions between episodes and seasons. It implicitly makes the show dependent on the outcome of the plot, and while it's eminently gripping, by design it makes it harder to enjoy the journey to get there.

Where there's smoke there's disappointment

There's truly no greater mascot for "Lost" and its spirit of general incoherence than the smoke monster. Initially, it's pretty accurately named, as it appears to be a sentient cloud of black smoke that kills Oceanic 815's pilot and knocks over trees menacingly. But soon, it starts appearing as the characters' dead relatives. Locke describes it as "beautiful" but doesn't explain beyond that. Later, it robs us of a great character in Mr. Eko by killing him seemingly at random in Season 3.

A more accurate name would be The Smoke Monster Slash Dead Relative Ouija Board, although it also appeared to several people as Jack's dad Christian Shephard, even though only Jack would recognize him. Finally, after many more confusing events, we learn that it was The Man in Black all along. The evil brother was locked in conflict for centuries with the equally mysterious Jacob and had been stuck in smoke form since an encounter with the bright light known as "the Heart of the Island." The point being, The Man in Black/Smoke Monster was less of a character or villain than a conceptual dustbin into which the writers of "Lost" swept disparate plot threads they couldn't otherwise explain.

Everything concerning Walt

The most memorable quote from "Lost" should be one of its many portentous and gasp-inducing lines: "Not Penny's boat" or "We have to go back!" or something similar. But because of the time it devotes to one father's search for his missing son, and then subsequent near-complete lack of follow-up when the character disappears from the show, fans mostly remember Harold Perrineau's constant yelling of "WAALLLLLLTTTT!!!"

Granted, actor Malcolm David Kelley aged a whole year from season to season, when only a few days would have passed on "Lost," so it's understandable that the writers needed him to fade from the narrative. On the other hand, the writers probably should have considered that when they made him such a key figure of concern in the first few seasons. The willingness to pivot away with a shrug from the endless amount of time spent on Walt was a sign of many issues to come. What were Walt's abilities? Why did he warn Locke not to open the hatch? What did the Others do to him while they were holding him? What did he know? WALT!!!

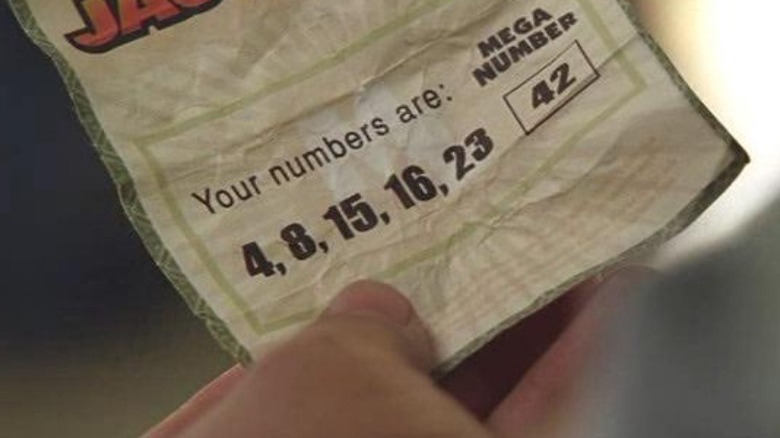

The runaround with the numbers

Much like Walt, the recurring string of numbers holds significance mostly just because "Lost" says so. The show's universe includes the sequence 4, 8, 15, 16, 23, and 42 in so many disparate places that it defies any sort of causal logic and functions almost more as an in-joke for the writing staff of the show, or a mildly fun Easter Egg hunt for the most devoted fans. They ultimately and most significantly correspond to the various "candidates" of the survivors to replace Jacob as protector of the island.

There are several strange steps between that supposed origin and Hurley's encounter with them in a mental hospital, which leads him to win the lottery and ultimately believe they're cursed. They're also the serial number on the hatch and the numbers Desmond has to enter, and on and on and on. By the time you start hearing about "The Lost Experience" AR game and something called "The Valenzetti Equation," it's clear the numbers are just a magic spell connecting disparate parts of "Lost," like a chaotic and tangled spiderweb.

Dueling love triangles

For all of its groundbreaking diversity, "Lost" spent a depressing amount of time boring us with the love lives of conventionally attractive straight white people. For a couple of seasons, leading man Jack and leading lady Kate seemed destined to lull us to sleep with TV's least-compelling "will they or won't they?" riff. Fortunately, the scruffy, wisecracking Sawyer swooped in to break up the moon-eyes and get together with Kate (although the romance awkwardly began while they were locked in a cage by the Others with Jack watching nearby).

Later, it's Sawyer and Juliet that have an actually pretty compelling, time-travel–bonded romance, but we have to put up with Kate and Jack on the fringes making everybody insecure about things. This annoying love quadrilateral even factors into the motivation to detonate the hydrogen bomb, as Jack is supposedly so heartbroken he wants none of this ever to have happened, and Juliet can't get comfortable with Sawyer's ex. What are we, in middle school? People's lives are at stake, "Lost." You could have spared us the gossip.

The Others were a real bother

The Others are another great encapsulation of what made "Lost" so frustrating on the whole. For two seasons, they're mysterious bogeymen. Are they feral inhabitants of the island, perhaps native to it? Nope, there's been one posing as a crash survivor the whole time. They kidnap Claire and Walt, and their leader, Ben Linus, is obviously a duplicitous and evil person. In Season 3, we learn that while they're a little kidnap-happy, they're not entirely evil. They're normal people trying to protect the island, and the real threat is from the outside.

For the rest of the show, they gradually become indistinguishable in purpose and practice from the Oceanic survivors, even though the drama of the show thus far has been thinking of them as, well, "the others." By the time you're trying to understand the incomprehensible rivalry between Ben Linus and the wealthy Charles Widmore, which seems to have arbitrary "rules" of engagement that mirror the rules between Jacob and the Man in Black, you get lost in how the Others fit into the story in the first place. The Others get a new leader in the end, but don't really factor into the endgame of "Lost" in a significant way. They're just a feint for the first half of the show while it was figuring out what to do.

Conspiracy versus cosmology

"Across the Sea," the second to the last episode of "Lost," should have been a triumphant moment in storytelling. After the better part of six seasons, answers about the larger conflict happening outside the survivors' comprehension are finally revealed. But almost as much as the finale, the episode was met with confusion and frustration from a galvanized viewing public. The whole story of "Lost" is a quasi-biblical story about brothers in eternal, supernatural conflict? And the Island is little more than a fairy-tale backdrop for this story? What?

The episode lays bare something fundamental about the calculus of "Lost." The show spent six years puzzling our minds with questions that presumably had rational explanations. What were the numbers? What was the smoke monster? What was the DHARMA initiative trying to accomplish? But in the end, the vast majority of the machinations of the plot are a result of supernatural, irrational powers and actions by two characters whom we barely even know. The reliance on a deepening mystery that supposedly takes place in a universe like our own governed by familiar laws of physics turns out to be a bait-and-switch for a larger allegorical conflict. As preparation for the finale, "Across the Sea" does its job by softening the blow; but as a long-awaited curtain pull on the story at large, it's a shocking and abrupt turn.

What about the hydrogen bomb?

We'll get to the specific nature of the flash sideways in Season 6, but "Lost" is supremely frustrating in that it saves the big reveal until the series finale. Season 5 ends on a huge cliffhanger, as Juliet detonates a hydrogen bomb meant to sink the Island and alter time itself so that none of the events of the show ever happened. As Season 6 unfolds, it seems very plausible that they're depicting that alternate timeline, as it depicts all the major characters living different lives that have little to nothing to do with the Island.

Of course, to put it mildly, that's far from what they turned out to be. So "Lost" essentially revises the key to one of its biggest cliffhangers, and in the process completely invalidates the sacrifice of one of its best characters. It also raises a lot of questions about how the Island is even habitable if a hydrogen bomb went off in the '70s and the timeline remained the same.

In the afterlife

The flash sideways scenes in Season 6 turn out to be glimpses of the afterlife. Regardless of the particulars, in retrospect, it seems like a fundamental misstep for "Lost" to confirm that an afterlife exists, because it cuts the basic dramatic tension of every scene in the show off at the knees. "Lost" is at heart a tale of survival. Part of its huge popularity is that it taps into a primal drive, like a "Far Side" cartoon about people trapped on a deserted island.

But if there's a confirmed afterlife within the world of "Lost," what drama is there to re-watching it and worrying about the characters being in danger? They'd just be getting an earlier ticket to the chill afterlife where Jack's dad explains everything calmly and everyone smiles at each other. The "Lost" afterlife isn't just saccharine and unnecessary, but also robs viewers of the chance to find meaning in the characters' deaths. It condescendingly takes the emotional processing out of our hands and says, "Don't worry, this is how it was meant to be."

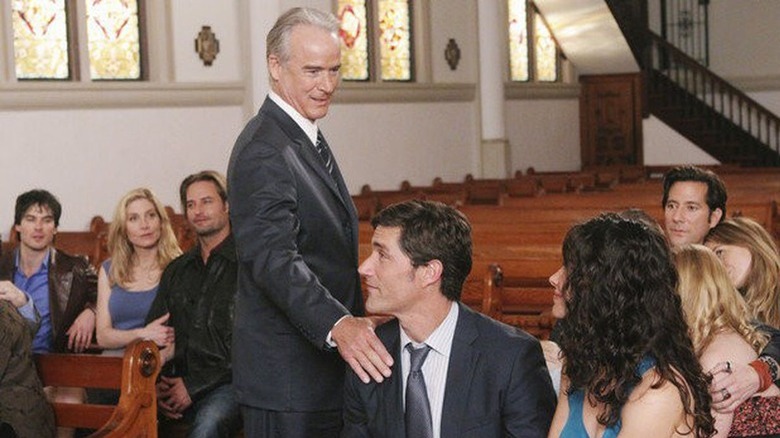

One of the worst finales of all time

Even if you're on board with the flash sideways world as a strange New Age purgatory, "Lost" handles it pretty terribly in a finale that intercuts mildly confusing action sequences with what just seems like the cast wrap party. It becomes impossible to care about the battle between Jack and The Man in Black/Zombie Locke once you get the reveal anyway, because your head is spinning with too many metaphysical questions about the weird Unitarian church that all the island survivors go to.

Why is everyone smiling like they're on laughing gas? Why is Sayid with Shannon, whom he dated for like two months? The explanation—that everyone has gathered (once they're all presumably dead in the future) in this place because they knew the time they spent on the Island together was special and significant—is pat and unsatisfying. It feels like "Lost" insisting on its own profundity, which is in no way earned and makes an assumption of goodwill on the part of the viewer. "Lost" had so many loose ends and rabbit holes that no finale would please everyone, but "The End" really feels like it was specially crafted to anger the most people by raising more questions than it answers.