The Craziest Details About For All Mankind's Alternate Timeline

The competition between the United States and the Soviet Union to be the first to launch a human being into space — and later, to the moon — was an era-defining event of the 20th century. The two nations, locked in an escalating Cold War, were racing to establish the high ground in preparation for a global nuclear conflict that, thankfully, has never come to pass. The space race excited the imaginations of ordinary people around the world, and yielded advancements in both military and consumer technologies. After American astronauts landed on the lunar surface in 1969 and the Soviets failed to do the same, the competition for space dominance gradually fizzled out, as did enthusiasm and funding for space exploration in general.

The Apple TV+ sci-fi series "For All Mankind" depicts an alternate version of the space race in which Soviet cosmonauts were the first to land on the moon. Rather than concede the contest to its communist rivals, the United States sets a new goal: establishing a permanent moon base. The continued competition between the two global superpowers changes the course of history, impacting not just the future of the space program but the grander shape of international politics. Each season of the series follows this alternate history into the following decade, and by the time the show's timeline reaches 1995, the world is significantly different from what we remember.

While the focus of the show is on America's astronauts and their families, "For All Mankind" — with the aid of its supplementary specials "One Giant Leap" and "Another Giant Leap" — reveals how the supercharged space program has influenced the lives of billions in ways both superficial and profound.

There are some different faces in the White House

One of the first indications that the timeline of "For All Mankind" diverges well beyond the history of the space program comes in the first episode when a news anchor announces that in response to the Soviets' surprise moon landing on June 26, 1969, Senator Ted Kennedy has cancelled his planned trip to Chappaquiddick Island. In our timeline, Kennedy's visit to Chappaquiddick to meet with some of his late brother Robert's campaign staff took a shocking turn that resulted in the death of a young woman. On July 18th, 1969 — two nights before the crew of Apollo 11 landed on the moon — Kennedy was behind the wheel of a car when it careened off a bridge and into the pond below. His passenger, 28-year-old speechwriter Mary Jo Kopechne, drowned in the vehicle. The storm of controversy surrounding the incident led Kennedy to cancel his plans to run for president in 1972. Instead, the Democratic Party ran Senator George McGovern, who was defeated in a historic landslide by Republican incumbent Richard Nixon.

In the "For All Mankind" version of history, Ted Kennedy remains in Washington for the Apollo 11 launch, avoids the Chappaquiddick disaster, and consequently defeats Nixon in the election of 1972. This has a ripple effect that shifts the result of every subsequent U.S. presidential election. Controversy still finds Kennedy during his first term, leading Republican Governor Ronald Reagan to win his first presidential bid in 1976 with running mate Richard Schweiker, instead of in 1980 with George H.W. Bush. Neither Bush nor his son become national figures. After two terms, Reagan is succeeded by Democrat Gary Hart, and then by (fictional) Republican and former astronaut Ellen Wilson in 1993.

The U.S. is closer to gender equity

In the "For All Mankind" timeline, the Soviet Union not only lands a man on the moon before the United States, but it also follows up this achievement by landing a woman on the moon in its very next mission. This mirrors the trajectory of the USSR's real-life orbital program, which launched cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova into orbit in 1963, 20 years before Sally Ride became the first American woman in space.

In the first season "For All Mankind" episode titled "Nixon's Women," the image of (fictional) female Soviet cosmonaut Anastasia Belikova on the moon becomes an overnight sensation and a symbol of female empowerment, even in the United States. Rather than allow the appearance that the communists offer greater opportunities for women than capitalist America, President Nixon orders that NASA's 1970 class of astronaut candidates to be all-female. The class' four graduates, Molly Cobb (loosely based on real-life aviator Geraldyn Cobb), Danielle Poole, Tracy Stevens, and Ellen Wilson become worldwide icons.

The promotion of women into the high-prestige, high-pressure world of the space program helps to rally public support for the Equal Rights Amendment, which is ratified in 1974. The real-life Equal Rights Amendment, which would federally codify that no rights can be denied or abridged on the basis of sex, passed in the House of Representatives and the Senate in the early 1970s but was passed by only 35 of the 38 state legislatures required to become a constitutional amendment. The ratification deadline officially expired in 1982.

Just as the real-life space program has helped to lift four NASA astronauts into public office, Ellen Wilson of "For All Mankind" makes the leap from space flight to politics in the mid-1980s. In 1992, she is elected the first female president of the United States.

Technology is decades ahead

In our timeline, the space program's demand for technological advancement has led to the invention or improvement of many technologies that are now considered commonplace. We have space exploration to thank for today's solar power cells, memory foam mattresses, household insulation, insulin pumps, and even the cameras on our cell phones. The Apollo program also jump-started the mass-production of microchips, which brought about our modern digital age. Our world now depends heavily on satellites for communications, navigation, and weather monitoring.

"For All Mankind" posits that a continued, sustained space race would require more and more ambitious technologies to match, speeding the pace of innovation such that the world would enjoy some advancements decades ahead of schedule. Live desktop video teleconferencing is utilized by U.S. government officials as early as the 1980s. Characters can be seen using iPods (in case you forgot this is an Apple show), which debuted in 2001 in our timeline, as early as 1995.

In an interesting twist that's only been explored only in the show's companion web series "Another Giant Leap" so far, this accelerated pace of consumer technology does not extend to the Internet. In fact, in the "For All Mankind" timeline, the U.S. government has refused to lift restrictions on civilian use of their computer network, denying the public the ability to create a true World Wide Web. We're not given a specific justification for this, but one imagines that it has something to do with heightened security during the now-endless Cold War with the USSR. Removing the Internet from history will make the "For All Mankind" version of the 2000s — which we are likely to see in the show's fourth season – totally unrecognizable.

Communism catches on across the globe

Along with the military implications of mastering local space, the public competition between the Soviet Union and the United States to achieve superior space technology was also seen as a demonstration of the relative value of their respective economic systems. The mid-20th century saw many nations that had previously been colonized by European and East Asian powers gaining their independence, and both superpowers wanted these nations to adopt their way of life. By beating the Soviets to the moon, the United States government hoped to prove that capitalism could outpace communism in building the 21st century.

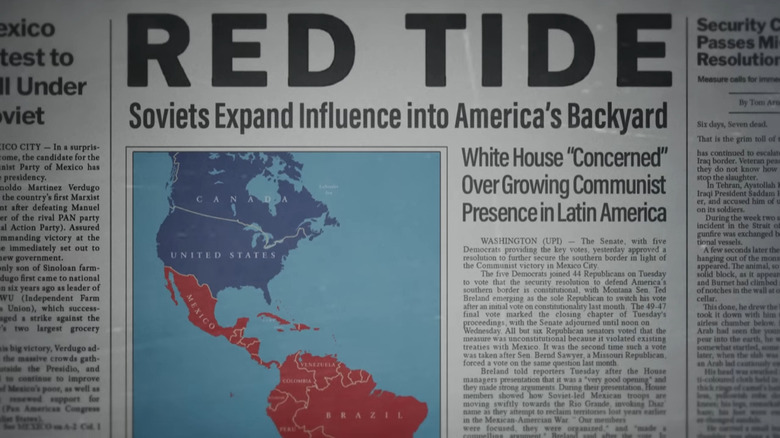

In our history, the Cold War between capitalist and communist nations essentially ended in 1991 with the dissolution of the USSR. In the timeline of "For All Mankind," the Cold War is still going strong in the mid-1990s, as the Soviets' influence keeps expanding into Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Global confidence in communism is at an all-time high as the U.S. and USSR are neck and neck in the race to land on Mars in 1995.

The impact of the space race on the "For All Mankind" timeline is much more than symbolic, as both superpowers choose to deprioritize military proxy wars in favor of the conquest of space. Neither government seems interested in invading countries that threaten a transition away from their favored economic system, with the U.S. pulling out of Vietnam three years ahead of schedule in 1970 and the Soviet Union deciding not to invade Afghanistan in 1979. "Another Giant Leap" reveals that the Communist Party is elected into power in Mexico and joins the Soviet coalition in 1989. American President Gary Hart declines to cut ties with Mexico, signaling a commitment to coexistence between capitalist and communist neighbors.

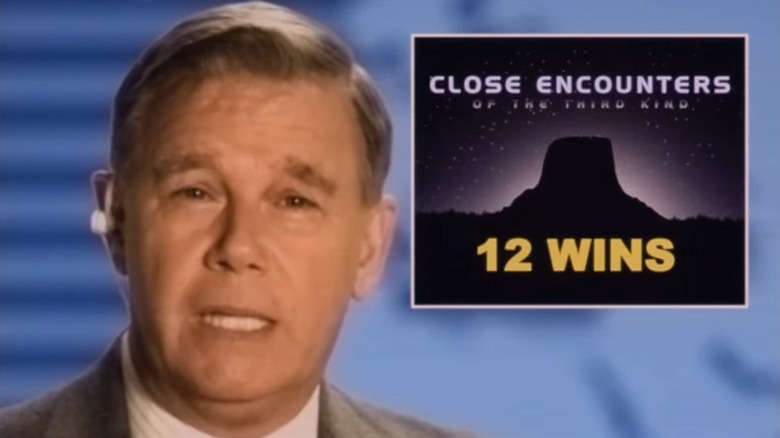

Close Encounters wins best picture

The continued focus of national attention on the space race slightly alters the history of popular culture. In a segment of "For All Mankind's" companion series "One Giant Leap," a 1978 news broadcast reveals that, in this universe, Steven Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" sweeps the Academy Awards, winning all 12 of the categories in which it's nominated, including best picture and best actor for Richard Dreyfuss.

In the real 1978 Academy Awards, "Close Encounters" won a single Oscar for best cinematography, but lost its other seven categories, including best director for Spielberg. Oddly enough, Dreyfuss still won best actor, but for the romantic comedy "The Goodbye Girl." Spielberg would lose best director two more times before finally winning for "Schindler's List" in 1994. Taking home an Oscar much earlier — and for a science fiction film, no less — would likely alter the course of his entire career, and of American film history in general.

The events of "For All Mankind" themselves also become the subject of hit movies in their universe, most notably "Love in the Skies," in which Meg Ryan and Dennis Quaid portray "For All Mankind" original characters Tracy and Gordo Stevens. The film is a blockbuster success, though we're not told whether or not it takes home Oscar gold.

The U.S. goes nuclear

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, many power companies in the United States pursued a transition from coal and oil-based power plants to the relatively new technology of nuclear fission. While nuclear power had always faced vocal opposition on various fronts — citing safety, environmental, and economic concerns — the most devastating blow to nuclear energy in the United States came in March of 1979, when the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, nearly experienced a total meltdown. The accident greatly reduced public confidence in nuclear power and slowed the country's move away from fossil fuels.

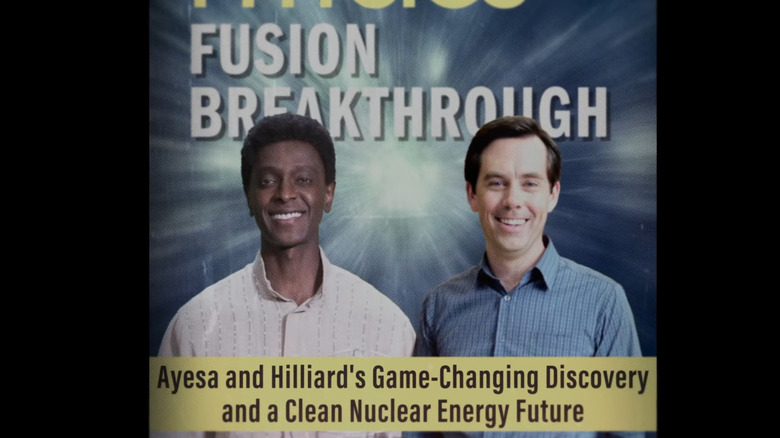

In the time jump montage that opens Season 2 of "For All Mankind," we learn that their universe's Three Mile Island accident is averted thanks to technology developed for NASA's nuclear-powered Jamestown moon base. Nuclear fission remains a popular alternative to fossil fuels, and the U.S. continues to invest in it. Lunar mining also yields the new resource of Helium-3, which eventually allows for the development of cleaner, more powerful nuclear fusion technology.

In the news flashes at the start of Season 3 of "For All Mankind," we are explicitly told that the course of climate change has significantly slowed due to the reduced use of fossil fuels, possibly avoiding the greatest existential threat to the planet Earth in the 21st century.

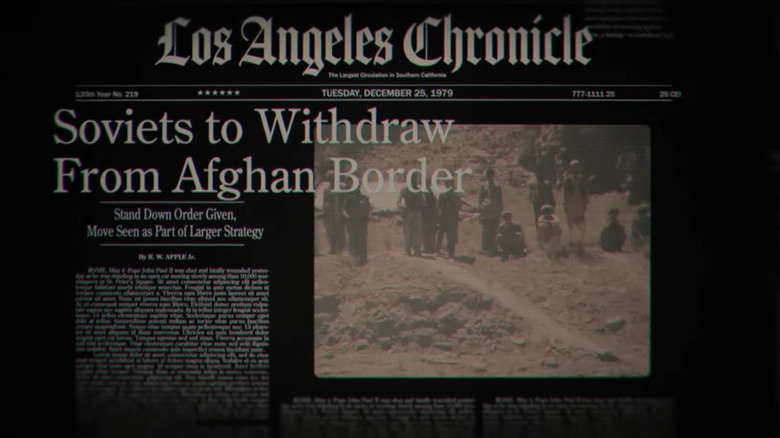

Middle East politics are totally different

In order to prioritize their space race budgets, a number of capitalist-communist proxy wars of the late 20th century do not appear to take place in the version of history that unfolds on "For All Mankind." Explicitly, the Soviet-Afghan War that tore up Afghanistan for decades is avoided when the Soviets retreat from the border in 1979. In our timeline, this is one of the most pivotal conflicts in modern history, snowballing into a series of bloody civil wars in the country that eventually installed the Taliban into power. The United States would later invade Afghanistan in 2001, citing the Taliban government's sheltering of terrorist leader Osama bin Laden as cause, leading to another 20 years of war. U.S. President George W. Bush expanded his "War on Terror" to justify invading Iraq two years later.

Avoiding the Soviet-Afghan War would have a massive historical impact on the as-yet-unseen 21st century of the "For All Mankind" timeline, where it is likely that the global "War on Terror" does not occur, at least not in the form we have experienced it.

This isn't the only change in Middle East politics seen in "For All Mankind." The Season 2 premiere's time skip montage reveals that the 1978 Camp David summit between Egypt and Israel fails to end in a treaty. In our timeline, the Camp David Accords stabilized relations between the long-warring neighbors and established the right of the Palestinian people to govern themselves. In addition, "Another Giant Leap" explains that U.S. President Gary Hart, who is in office instead of George H.W. Bush, decides not to intervene in Iraq's 1990 annexation of Kuwait. It's likely not a coincidence that, by the early 1990s in the "For All Mankind" timeline, the United States has pivoted to nuclear power and is no longer dependent on foreign oil.

The Beatles go on a reunion tour

Some of the changes in the "For All Mankind" universe cannot be easily traced back to the events of the show's core space race narrative. Instead, a few of the details of the show's alternate history can only be attributed to the butterfly effect – distant and unpredictable ripples caused by a single, seemingly unrelated change in the timeline. In the opening montage of "For All Mankind" Season 2, which catches the audience up on world events between 1975 and 1982, we learn that musician and activist John Lennon survives an assassination attempt in New York in 1980. The companion series "One Giant Leap" expands on these events, showing two uninterrupted minutes of a news broadcast from that evening.

In this news break, a reporter speaks to a fellow musician who is present when Mark David Chapman fires a revolver at Lennon. The (fictional) keyboardist recalls seeing Chapman aim his weapon and diving on him as he fired, upsetting Chapman's aim. Lennon's wounds prove to be nonfatal in this universe.

In the following season's catching-up montage, which covers 1984 through 1992, we see a glimpse of another news broadcast about a Beatles reunion tour kicking off in front of a massive outdoor audience in Chicago in 1987, seven years after the band's singer and guitarist was killed in our timeline. This event doesn't seem to have had any long-term seismic effects in the world of music — when the season kicks into gear, it's still the age of grunge — but it is, nevertheless, a cool "what if?" in the alternate history of "For All Mankind."

Margaret Thatcher and Pope John Paul II are assassinated

One of the ways that "For All Mankind" differentiates its timeline from ours is by reversing the results of various political assassination attempts throughout the second half of the 20th century. The Season 2 premiere's array of news broadcasts briefly highlights three such changes, though they don't all pass close scrutiny as logical events in the show's revised timeline. First, in 1981, Pope John Paul II is successfully assassinated in St. Peter's Square. In our timeline, Turkish mercenary Mehmet Ali Ağca's attempt to kill the pope fails. However, the real Ağca's stated justification for the attempt was a protest against the Soviet Union and United States' proxy wars in El Salvador and Afghanistan, at least one of which does not take place in the universe of "For All Mankind."

We also learn that Egyptian President Anwar Sadat survives an attempt on his life that same year. In our universe, Sadat was shot by officers in his own military on October 6, 1981. Their disenchantment with his leadership has been attributed, in part, to his treaty with Israel signed two years earlier. In "For All Mankind's" timeline, this treaty is explicitly never signed.

This same montage also tells us that British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher does not survive the "For All Mankind" version of the 1984 Brighton hotel bombing, a real-life assassination attempt, for which the Irish Republican Army claimed responsibility. This event seems largely divorced from the larger political narrative of the series, though it's conceivable that it will have ramifications for future seasons of the show.

Michael Jordan plays for the Portland Trail Blazers

The world of sports is also affected by the reverberations of the "For All Mankind" alternate history, as revealed through newspaper and television headlines during the show's seasonal time jumps. For instance, the "Miracle on Ice," in which the U.S. Men's Hockey Team defeated the dominant Soviet Union in the 1980 Olympics, doesn't happen. Instead, the USSR takes home the gold.

In 1986, the FIFA World Cup Final between England and Argentina has a different result, as Diego Maradona's infamous "Hand of God" goal is (properly) ruled as a foul. In our universe, Argentina's Jorge Valdano kicked the ball towards teammate Maradona, who deflected the ball into the goal with what, to the referees' eyes, appeared to be his head. To the viewing audience at home, it looked much more like Maradona used his hand, which is illegal in football. The referees upheld the goal, making it one of the most controversial scores in all of sports. In the "For All Mankind" universe, some eagle-eyed official disqualifies the goal, and England wins the world cup.

The most seismic change to U.S. sports history, however, comes in 1984 when the Portland Trail Blazers use their first-round draft pick to sign Michael Jordan, just one pick before the Chicago Bulls. Portland passing on Jordan in favor of center Sam Bowie was a huge mistake in hindsight, as Jordan became a cultural icon who led the Bulls to one of the most successful runs in the history of basketball. How the existence of a moon base helped the Blazers come to their senses, we'll never know.