The Ending Of Netflix's Resident Evil Season 1 Explained

Let's address the inevitable right off the bat. Although an encyclopedic knowledge of Capcom's "Resident Evil" game series — or even a relative familiarity with the incomprehensible narrative at play in the IP's film franchise — may help you appreciate a number of the flourishes and references in Netflix's "Resident Evil," such knowledge is neither necessary nor ultimately that helpful when it comes to understanding the meaning behind the just-released reboot. If you're looking to understand how directly the series draws from or relates to its source material, IGN's "Resident Evil: The Story So Far" and Netflix's breakdown are both excellent places to start. If, however, you're attempting to decode the chilling and hyper-relevant commentary embedded in the reimagining's through-line and ending, you're better off directing your attention to the basic theme the story has been addressing, consistently, for just under three decades now.

Created and co-written by Andrew Dabb (of "Supernatural") and starring Lance Reddick ("Bosch," "John Wick") as a very different iteration of Raccoon City's longtime antagonist, Albert Wesker, the series approaches the apocalyptic narrative via two separate timelines. The first takes place in New Raccoon City in 2022, over two decades after the eradication of (old) Raccoon City. The second brings us to 2036, and a post-apocalyptic London overrun by (what else) T-virus-created zombies. That Dabb sets the better part of his story in our current world is of no small consequence. In fact, it tells us everything we need to know about the not-so-subtle message his ending relays.

Netflix's Resident Evil honors the game's thematic origins

Since the "Dawn of the Living Dead," the zombie apocalypse has been used by artists across a variety of mediums to act as a cautionary tale regarding the dangers of an era's current path. While Romero's sequel exposed the willful ignorance of the Regan era, Capcom's "Resident Evil," released in 1996, spoke to a society grappling with the consequences of the Greed is Good '80s, The Gulf War, and an increasing awareness of the not-always-benevolent nature of big pharma. Elizabeth Wurtzel's "Prozac Nation" had come out just two years prior, and a newly-public company called America Online had just leapt, in the course of a year, from 1 million to 5 million members (via CNBC). The disillusion of the '60s and '70s had returned, but in the form of a general malaise and cynicism, aided by a boom in technology that was evolving rapidly, forever altering the mechanics of society with each new update and offering.

The malevolent entity at the center of "Resident Evil," the Umbrella Corporation, brilliantly encapsulated the era's simultaneous dependence on, and wariness of, profit-hungry corporations, while the game's various monsters made tangible the worst-case-scenario fears of an increasingly skeptical generation. While the game evolved with each of its numerous iterations and spin-offs, this thematic core remained the same. And while the "Resident Evil" films get a lot wrong about the games and have an otherwise convoluted and confused the storyline, even they've been unwavering in their game-honoring subtext and message. Dabb's reimagining of the now well-worn zombie yarn does this as well, but with one very important tweak.

Resident Evil speaks to some of today's most relevant threats

Again, you don't need to sift through the chaotic timeline of the "Resident Evil" films to appreciate Netflix's new series, but that doesn't mean its devoid of any and all cinematic reference. Oddly enough, however, the two films that feel like the most predominant influences on Dabb's take have nothing whatsoever to do with the IP, or, for that matter, with zombies, though they're no less horrifying for it.

The revelations provided in 2021's "The Crime of the Century," a two-part documentary detailing Purdue Pharma's lethal and fraudulent role in the opioid epidemic, and 2020's "The Social Dilemma," an exposé on Surveillance Capitalism, growth hacking, and for-profit behavior modification (aka "persuasive tech"), both loom large over the eight-episode series. Through dialogue, imagery, and a litany of not-so-subtle allusions, Dabb's series, and its ending in particular, directly reference the realities laid out in these films, otherwise known as our current, actual reality.

In doing so, Netflix's contribution to the story does something the games, films, and spin-offs have not. Though the underlying antagonist in the "Resident Evil" games has always been a greedy, profits-over-people corporate machine invested in global domination achieved through a monopoly on the mechanisms of modern warfare, it's mostly maintained a kind of facelessness, a vagueness that allowed it to serve more as a template than a direct commentary. Netflix's "Resident Evil," on the other hand, imbues its central villain with a clear and unnervingly recognizable specificity.

Netflix's Resident Evil is a big tech-big pharma cautionary tale

"Resident Evil" is not, therefore, a portrait of a dystopian future (or reminder of a misstep in the past, like "Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City"), but a reflection on an increasingly dystopian present. The notorious and much-discussed T-virus is still the deadly substance that kicks-off the zombie apocalypse, but Umbrella's path to power and domination has evolved along with our world. Forget unleashing un-killable mutants (or "bio organic weapons") on other countries. In 2022, the ability to control a population via medications and devices upon which its people are wholly dependent is a much more efficient, unstoppable weapon (for the latter, see: Russia's involvement in the 2016 U.S. election, or the crisis in Myanmar).

In "The Social Dilemma," big tech turncoat Tristan Harris explains the result of persuasive tech: "two billion people," he says, "will have thoughts that they didn't intend to have because [of a] designer at Google." The product our apps are selling, then, isn't simply data, but the ability to manipulate our thoughts and actions. This is happening to each and every one of us every time we reach for our smartphones, and it's echoed directly by Paola Nuñez' Evelyn Marcus (an Umbrella legacy and its new CEO), who wants to use the company's new T-virus-laced anti-depressant, JOY™ , to take this real world mind control to a whole level. "F*** Google," she says, "F*** Zuckerburg — they deliver eyeballs. Umbrella will deliver minds." Both her underlying motivation and her rush to bring the drug to market play a major role in the series' ultimate thesis, as does the drug's less secretive use.

Dabb makes direct references to real corporations

Despite Wesker insisting that the T-virus element in JOY™ is still too unstable to bring the drug to market, Evelyn demands he make it happen within the next six months, so that she might successfully bring the flailing company back to life. At one point, a reporter explains Umbrella's past and present as follows: "A company besieged by legal scandal, and falling stock prices, is now trying to reinvent itself with a major push into direct-to-consumer drugs. Critics say that the company is operating at a dangerous burn rate."

The allusion to both Purdue and Insys Therapeutics (the now-bankrupt company responsible for Fentanyl, per The Wall Street Journal) is both clear and cutting. Equally clear in their commentary are the opioid withdrawal-mirroring side-effects of JOY™ (aggression, sweating, rapid heartbeat, hallucinations) and the "zombifying" effect that high doses of the drug elicit. When Evelyn callously says, "So, we know what goes on the warning label," the reference to big pharma consistently blaming the user of a drug while ignoring their own irresponsible marketing and prescribing of that drug (via CT Mirror) is blindingly apparent.

That Umbrella's two different uses for their latest "weapon" involve manipulation and control through dependency (rather than monstrous brute force) marks a major turning point for the narrative — one that's brought into clear relief in the series' final two episodes. But in addition to this fresh and relevant twist on the story, there's an important thematic tie-in to the series' source material.

Gaslighting and good intentions are a rough combination

One of the more insidious elements of bad corporate behavior explored in both Netflix's "Resident Evil" and the games and films is the gaslighting upon which such capitalistic endeavors rely. "It's for your own good," Umbrella insists, as do our real world ads, apps, and pharmaceutical companies (see: this eerily dystopian Meta ad, wherein we're told that personalized ads help us find "something missing in [our] lives"). Combine this sales tactic with the initially good intentions that spark so many advances in science and tech, and you create a dynamic wherein both seller and buyer are locked in a one-way "road to hell."

This idea is most thoroughly highlighted by the last two episodes of "Resident Evil," wherein we learn that for all her flippant disregard of JOY™ users, and for all her power-hungry ambition, Evelyn might genuinely believe that her creation could "change the world," as she says several times, for the better. There's more than a few shades of the tragic tale of Theranos in Evelyn's repeated use of that phrase, but in having the Umbrella CEO allow her ambition to overtake her regard for human life and autonomy, "Resident Evil" is once again presenting us with a cautionary tale.

In the penultimate episode, we learn that Evelyn has been drugging her wife with JOY™ (by crushing it up, one of the most common misuses of Purdue's OxyContin, per the FDA), in order to keep her compliant. This marks the point of no return for the wife and mother, who'll later continue her mission despite the loss of her son.

Netflix's Wesker is riddled with meaning

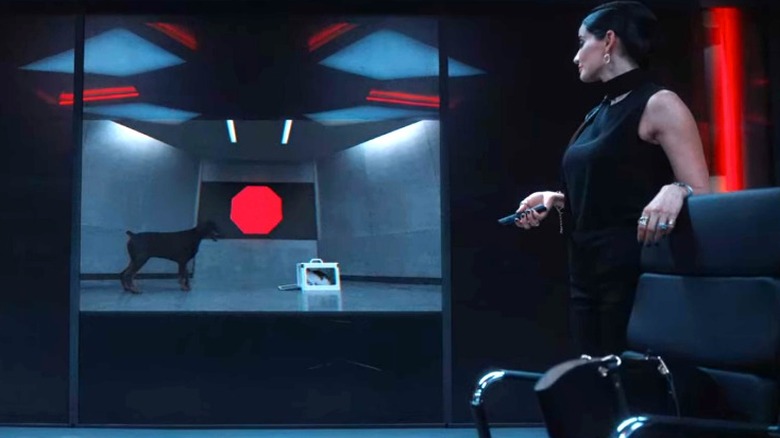

In contrast to Evelyn, the Wesker of Netflix's (admittedly polarizing) "Resident Evil" reboot never loses his humanity. This Wesker differs wildly from the one-dimensional villain of the games and movies, but with good reason. The hard-working dad with whom we're presented for the majority of the series is not, we learn in the end, the actual Albert Wesker. When Wesker needed a team of scientists to help him advance the virus, he created a handful of Wesker clones. Only two of these clones survive — Bert (whom Evelyn keeps locked up) and Albert (the dad we believe is Wesker for most of the show) — but they have serious health problems as a result of aging instantaneously.

In order to stay alive, Albert created his two daughters, Billie and Jade (in the 2022 timeline, Siena Agudong and Tamara Smart) using the latter's blood to stave off his symptoms. It's a simultaneously nasty and nuanced kind of parental need. Albert does love his daughters (whom Evelyn refers to as his "blood bags") as evidenced by his willingness to do anything to protect them. Here, again, the series is highlighting the not-so-straightforward nature of our push-pull relationship with scientific progress.

Yes, Wesker is using Jade, but he has no choice in the matter if he wants to live. He does, however, have a choice as to whether or not he'll sacrifice himself for her. This gap in what he can and can't control — his human weakness vs his human strengths — openly mirrors society's complicated need for pharmaceutical breakthroughs. Similarly, Umbrella's need to be both the disease and the cure mirrors our current technological conundrum.

Billie's decision boasts some major subtext

In the end, we learn that Adeline Rudolph's adult Billie (who was bit in 2022 and developed T-virus symptoms) decides to side with Umbrella, eventually finding a way to control even Evelyn, upon whom she was once dependent. Jade has gone in a different direction, working for a rebel university and studying the behavior of the zombies that now encompass the planet. Sister is pitted against sister as it's revealed that Billie, like her clone dad before her, needs Jade's blood in order to survive. In one of the most important final scenes of the series, we witness Billie's decision. "If I am sick, can you help me?" she asks Evelyn in the 2022 timeline. "I'm the only one who can," Evelyn says.

It's not hard to see this cause-of-the-sickness, owner-of-the-cure game-referencing dynamic in the call for companies like Facebook to fix the monster they created. Unfortunately, as data scientist Cathy O'Neil points out in "The Social Dilemma," this is a misguided ask. "We are allowing the technologists to frame this as a problem that they're equipped to solve," she says, adding, "that's a lie."

Evelyn and Umbrella may be able to keep Billie alive, but they do so at the cost of her very humanity. In the end, Billie's decision to rely on the corporation leads to her willingness to shoot her sister in the stomach, leave her for dead, and kidnap her niece to mine for blood.

Albert's death is heavy with visual commentary

You can't, the ending of reminds us, extinguish a fire with more fire. Billie is "alive," but no longer able to act or think beyond her own survival. This addiction-investigating ending is foreshadowed in a scene in the series' penultimate episode. As the girls' father Albert struggles to reject Evelyn's control in the build-up to the outbreak, she reminds him that willpower has nothing to do with his current situation.

"You need your medicine," she says, adding, "in about an hour, maybe less, the pain will become unbearable, and you'll give in."

Later, as he lays dying on the floor, begging his daughters for forgiveness, Evelyn leans over him and places a syringe of Jade's blood in his hand. It's a heartbreaking scene, and one that directly reflects the dynamic between an addict and their family, and an addict and their supplier. Purdue may not have literally put heroin needles in the hands of users, but through its lies and greed, it created an uncontrollable outbreak (not unlike a zombie outbreak) of individuals so addicted to over-prescribed opioids that they had little choice but to turn to the less expensive street drug when their dependence overtook their bank account (via CDC).

Despite the gutting symbolism of Albert's final few moments before he sacrifices himself to free (or, attempt to free) his daughters, the series eventually leaves us with some semblance of hope.

Resident Evil's ending pits preservationists against progressives

When Ella Balinska's adult Jade unleashes a mountain-sized, mutated Crocodile on Umbrella's basecamp, it's not simply a reptilian display of gamer fan service. The confrontation of past and future, of nature and technology, and of history and progress, are all brought to the foreground in the series' final moments. The fact that Umbrella's technology is able to tear at and destroy the very fabric of the origins of our world (literally, here, by tearing at the body of a creature that pre-dates our existence) is of obvious symbolic import. What's more, Jade aligning herself with the university — aka, the preserver of "the past" — is meant to stand in direct contrast to her sister's alignment with Umbrella. In their final exchange, Billie literally says, "I'm the future."

The series stops short, however, of implying the past is, by default, wholly superior. Yes, this future is heartless, bleak, infected, and driven by a manufactured dependence on a malevolent corporation. Yes, we got here (in the series, and, potentially, in reality) by allowing our complex need for progress to make us reliant on such a corporation, but this doesn't mean science and progress are, in and of themselves, a bad thing. The crocodile doesn't attack Jade's daughter, and though we've yet to learn why (there's always Season 2), it's strongly implied that Jade altered her DNA or used some form of science or technology to otherwise protect her offspring.

So, where does this leave us with regard to the message of Dabb's interpretation?

Bert's message informs the ending of Resident Evil

Plot-wise, it's a series finale that leaves us with more questions than answers. We don't know if Jade survives. We don't know if Billie will harm her own niece (though it certainly looks that way). We don't know what's special about Jade's daughter, and we don't know much about Billie's plans for Umbrella. We also don't know what will become of Evelyn, the university, or the world's remaining humans. Thematically speaking, however, the series finale ends on a fairly conclusive note — one that's simultaneously chilling and motivating.

By setting the onset of the apocalypse in our current year — and by focusing on two very real, very powerful yet complicated threats to our society — "Resident Evil" gives us the most terrifying apocalypse of the entire IP. This is happening now, it says. We carry this threat, this loss of independence through dependence, around in our pockets, charge it and feed it (and feed off of it), even as it feeds off us; even as it feeds, more specifically, off our brains.

Nevertheless, beneath the doom and gloom of the series' finale, there's some hope to be gleaned from Bert's guileless speech to a young and still-mostly human Billie. "No one's really okay," he tells her, "we're all just doing our best. In a world where it's way too easy to do your worst." In the end, this most recent installment of "Resident Evil" simply reminds us that while corporations aren't people, people still are. At least, for now.