Things That Happen In Every Toy Story Movie

The iconic "Toy Story" series from Pixar Animation Studios is anchored by four theatrical films spanning from 1995 to 2019. There's not a bad pick among the bunch, with the franchise's lowest critical score on Rotten Tomatoes belonging to "Toy Story 4" at a still-impressively high 97%. (For what it's worth, the lowest audience score of the four movies is for "Toy Story 2" at 87%.) These four movies shine as exemplary examples of the art of animation and the power of storytelling. The films connect with audiences in ways that few sagas are able to achieve, strangely reaching the core of our human selves through narratives built around pieces of sentient plastic.

While it would be belittling to reduce a franchise as prestigious as "Toy Story" down to a formula, since each film succeeds in being a worthy tale on its own merits, there are still patterns one can notice by taking a closer look across all four movies. Here are some of the things that happen in every "Toy Story" movie.

You've Got A Friend In Me

It was nominated for an Oscar after its inaugural appearance in the first "Toy Story" in 1995, and became the anthem for the entire series going forward, played not once, but twice in every "Toy Story" movie. "You've Got A Friend In Me," a song written and performed by Randy Newman, opens "Toy Story" with a sweet montage of Andy, a young boy, affectionately playing with Woody, his favorite toy. Over the four films, the song takes on new meaning as its lyrics come to embody the friendship of a number of different kids and toys.

Not only does Newman perform the song solo in "Toy Story," but he also sings a duet version of the tune over the end credits with Lyle Lovett. In "Toy Story 2," the song is heard within the in-universe "Woody's Roundup" vintage television show and again at the finale of the film, with a big band rendition performed by Robert Goulet voicing Wheezy the penguin. "Toy Story 3" places the original version by Randy Newman over a flashback montage from Andy's childhood and also places the song in its epilogue — this time in Spanish to go along with Buzz's newfound "Spanish mode," performed by Gypsy Kings, Nicolas Reyes, and Tonino Baliardo. "Toy Story 4" features the original Newman track once more in an opening montage that sees the passage of time from Andy to Bonnie, the toys' new owner now that Andy is grown up.

A deeply sad moment

Pixar creates notoriously emotional films, from "Up" to "Inside Out." The "Toy Story" movies are among their most thought-provoking, each with a moving moment that will undoubtedly elicit reflection and maybe even tears from the audience.

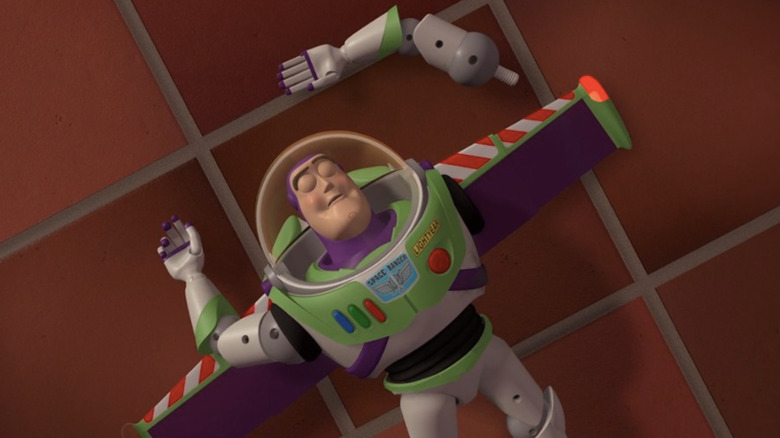

"Toy Story" sees Buzz, in his delusion of being a space ranger, jumping from a flight of stairs and losing his arm, subsequently crushed by his defeat and his entire worldview being shattered. Jessie's flashback song, "When She Loved Me," in "Toy Story 2" is among the saddest moments ever put onscreen, showing the doll's heartbreak over a child growing up and forgetting her. "Toy Story 3" faces the reality of Andy himself getting older and passing his beloved toys on to a new owner, the transition bringing reflection on the fragility of time and youth. "Toy Story 4" once more packs an emotional punch at its conclusion, which sees Woody departing from his lifelong friends to begin a new life with Bo Peep.

Each of these moments doesn't shy away from the matter at hand. They viscerally confront raw, complicated emotions that audience members can equate to their own life experiences, thus making the sequences in question all the more poignant. One thing's for sure: when watching a "Toy Story" film, make sure to have tissues nearby.

Tense story moments get interrupted by a human

Toys are alive within the world of the "Toy Story" movies, but they can't let humans know that. Anytime a human enters their presence, toys freeze, usually assuming a posed, smiling position that their manufacturer assigned them upon production. This often means high-stakes moments in the plot are interrupted if a human enters the room, which happens in all four movies.

In "Toy Story," Andy enters his room just after Woody accidentally pushes Buzz out the window. The pause in the action doesn't give Woody the time to explain what happened or make it right. A critical moment in "Toy Story 2" comes when Woody is nearly successful in convincing Jessie and Bullseye to come with him and be Andy's toys rather than be shipped to a museum in Japan. However, just as Jessie makes up her mind, Al enters the room and packs the toys up for their big flight.

Bonnie takes Woody home with her from the daycare center in "Toy Story 3," and Woody spends the pauses between her playtime to try to figure out where he is and how to leave. "Toy Story 4" includes a madcap chase in the antique store with Gabby Gabby and her henchmen running after Woody and Bo Peep, only to be halted by humans walking through the store aisles. These moments provide Pixar with creative opportunities to give audiences unique pacing that they won't find in other movies.

Toys intervene with human affairs

Sometimes for their own safety and livelihood, toys have to take matters into their own hands and intervene with something in the human world. Without being able to talk to humans or reveal that they're alive, the toys go to great lengths to save the day.

Pixar uses this device as a means to "explain" why nonsensical things might happen to us. It might just have been a toy making it happen all along! At the end of "Toy Story 2," Andy thinks his mom has bought him new toys — Jessie, Bullseye, and three squeaky Pizza Planet aliens — to welcome him home from camp, but his mom did no such thing. Likewise, the conclusion of "Toy Story 3" sees Woody writing on a Post-it note that Andy should donate his toys to Bonnie, and Andy thinks his mom wrote the note. In "Toy Story 4," to stall for time at separate points in the film, Jessie slashes the tires of the humans' RV and Forky messes with the RV's locking-unlocking mechanism, both much to the frustration of Bonnie's dad, who is dumbfounded at his rental vehicle's issues.

The one example of this thread that serves as an exception to the toys' strict rule of secrecy comes in the original "Toy Story," when Woody leads a coup against resident toy torturer Sid, Andy's neighbor. Woody scares the living daylights out of Sid by coming alive, but hopefully Sid learns his lesson.

The toys narrowly evade death

Life as a toy is apparently exhausting and often morbid. In every single "Toy Story" film, the toys find themselves in mortal danger that could have ended unpleasantly each and every time, but they always manage to survive and see another day to be there for their kid.

From the very beginning, there's no easing into this concept. We dive right in, with the first "Toy Story" showing nothing less than Buzz and Woody chasing a moving truck in the middle of the road before igniting an exploding rocket and careering through the sky. Talk about commitment — these toys' loyalty to their kid is unmatched. "Toy Story 2" again sees the gang placing themselves in harm's way in the middle of the road, this time while walking underneath traffic cones and causing a huge wreck in the process. Later in the same movie, they hijack a Pizza Planet truck and drive it through traffic. In "Toy Story 3," they nearly melt in an incinerator, just barely escaping doom.

Lastly, "Toy Story 4" shows Woody jumping out of an RV while it's moving to save Forky, and the movie concludes with Buttercup the unicorn trying to take control of the RV's driving from Bonnie's dad. Any one of these situations could have ended in peril, whether for the toys or for the humans they actively put in danger in the process, but of course, everything always turns out all right in the end.

A toy rejects their former dream

Toys have a lot of trauma. In every "Toy Story" movie, a character's dreams don't materialize the way they thought they would and they must confront their past aspirations to decide who they want to be from that point. Some of them become better toys in the process. Others become much worse.

Buzz realizes he's not a real Space Ranger in "Toy Story" after he attempts to fly and his arm falls off. Questioning everything he thought he knew about who he is, he quickly becomes depressed as he waits in Sid's room for the bully to destroy him. Woody gives Buzz a pep talk and helps him realize that just because he's a toy, that doesn't mean he doesn't have purpose. In "Toy Story 2," Jessie grieves for her former life with Emily, her owner who lost affection for her, but finds new hope in discovering she can start over with Andy.

"Toy Story 3" shows Lotso the strawberry-scented plush bear being accidentally abandoned by his owner, Daisy. Upon traveling back to her and realizing Daisy's parents replaced her original Lotso with a new bear, Lotso is filled with rage and is never quite the same. In "Toy Story 4," Gabby Gabby hopes she'll finally be adored by a girl named Harmony after her voice box gets fixed, but Harmony rejects her. Defeated, Gabby Gabby all but gives up until she helps a lost girl find her parents and fulfills her destiny as a toy.

Lost toys

Whether by fault of a human or their own meddling, toys wind up separated from their kid in every "Toy Story" movie. Woody and Buzz accidentally get left behind at the gas station in the original "Toy Story," finding themselves taking a detour at Pizza Planet and Sid's house before finally reuniting with Andy. In "Toy Story 2," a greedy toy collector steals Woody from Andy's house, and the other toys lead a rescue mission to get their pal back. Andy's mom mistakes a bag of toys for a bag of trash in "Toy Story 3," and the gang spends the length of the movie figuring out where they belong and how to get back. The third installment also shows a girl named Daisy accidentally abandoning her favorite plush toy, Lotso, at a roadside picnic.

"Toy Story 4" subverts the notion of a lost toy altogether by placing the subject as the thematic core of its narrative. Not only does Forky project himself out of an RV window, rendering him lost to Bonnie, but Woody discovers Bo Peep has been living as a lost toy for years, independent and without an owner. Her freedom shifts Woody's entire worldview, and he eventually chooses to go live with Bo. Being a lost toy — something he once lamented as his greatest fear when he was left at the gas station in the very first movie — is now a lifestyle he willingly chooses, his perspective shifted and his mind opened.

Real-life toys

In addition to the many eclectic toy characters that Pixar filmmakers create to serve the plot of each "Toy Story" film, the crew also includes real toys that audiences may have played with in real life. Every movie in the series features real toys among the ensemble.

For starters, among the main cast in all four movies is Mr. Potato Head, memorably voiced by the late Don Rickles, who's joined later in the series by Mrs. Potato Head, voiced by the late Estelle Harris. The Mr. Potato Head toy was first sold in 1952, but only included the detachable parts. You had to provide your own potato!

A number of real-life toys populate the series throughout, including the drawing tablet Etch-A-Sketch providing a map to Al's Toy Barn, a collection of Troll toys being cast as orphans on a runaway train during Andy's playtime, Barbie and Ken dolls playing a prominent role in taking down Lotso's dominion at Sunnyside Daycare, a vintage Chatter Telephone giving Woody an inside scoop on how to help his friends, and a plush depicting the main character from the Miyazaki film "My Neighbor Totoro" among Bonnie's toys.

While Rex didn't exist in the real world as a toy prior to "Toy Story," his manufacturing has quite a bit of backstory. He tells Buzz that he's from Mattel, before correcting himself to explain, "Well, actually, I'm from a smaller company that was purchased by Mattel in a leveraged buy-out."

Mr. Potato Head disassembles

It must be a proven audience-pleaser to have Mr. Potato Head get knocked over or otherwise completely misalign all his detachable features, because it happens in one way or another in every "Toy Story" adventure. The toy is well-known and beloved for its creative ability to mix and match different variations of the spud's eyes, ears, arms, nose, mouth, shoes, and hat, and Pixar utilizes all four films to leverage this unique character trait, whether through a quick gag or as a plot device.

At the climax of the first "Toy Story," Buzz and Woody blast into the air attached to a rocket, and drop off Andy's remote-control car in a moving van as they careen skyward. The rest of Andy's toys watch the spectacle unfold from the moving van, whose back door is wide open. Of course the toy car violently smashes right into Mr. Potato Head, sending his parts flying every which way. In "Toy Story 2," as the gang navigates an elevator shaft in Al's apartment, Rex slips and falls right on top of poor Potato Head, sending his parts everywhere.

"Toy Story 3" has the character becoming Mr. Tortilla Head, briefly abandoning his potato body for the sake of escaping the daycare. Rex's long tail clumsily knocks over Potato Head in "Toy Story 4," spilling his parts all over Bonnie's family's RV. Funny, clever, and evergreen — Mr. Potato Head is a guaranteed laugh.

New music written by Randy Newman

While the Oscar-nominated "You've Got A Friend In Me" remains an anthem throughout the entire "Toy Story" series, Randy Newman also wrote additional songs for all four movies.

The soundtrack for the original "Toy Story" includes the peppy "Strange Things," which scores a montage showing the ways Buzz makes himself at home as a new toy in Andy's room. The more somber "I Will Go Sailing No More" plays later when Buzz accepts the reality that he's not a Space Ranger. "Toy Story 2" debuts both the Oscar-nominated "When She Loved Me," the ballad sung by Sarah MacLachlan as Jessie reflects on her former life with Emily, and "Woody's Round-Up," a zippy theme song for Woody's vintage television show.

"Toy Story 3" features the Oscar-winning "We Belong Together" playing over its epilogue, tying up the loose ends of the movie and showing the characters as they begin their next chapter. Finally, "Toy Story 4" spotlights the Oscar-nominated "I Can't Let You Throw Yourself Away," performed by Newman, as Forky attempts on numerous occasions to literally throw himself in the trash. Also in the film is "The Ballad of the Lonesome Cowboy," performed by Chris Stapleton over the end credits, as a melody meant to emulate Woody's journey.

In addition to writing and often performing these songs, Newman also composed the background score for all four "Toy Story" movies.

Woody gets angry

Woody is a headstrong character who likes to make a plan and stick to it, often while neglecting to empathize with the well-being of his friends. In every "Toy Story" movie, at some point, Woody gets angry and stomps away, but he always comes around in the end.

The arrival of Buzz in Andy's room pushes Woody to his limits in the first entry in the series. Frustrated with Buzz getting more attention from Andy than himself, Woody concocts a plan to trap Buzz behind a dresser, but accidentally knocks Buzz out the window instead. In "Toy Story 2," rather than rejoicing when Buzz and the rest of the toys arrive to rescue him from being flown to Japan, Woody gets rather testy and turns his back on his friends, choosing (temporarily, at least) to go to the museum. "Toy Story 3" shows Woody having an outburst in which he accuses the other toys of not being loyal to Andy, when in reality they'd just rather move on with their lives instead of being cooped up in an attic.

"Toy Story 4" includes another signature Woody argument as his plan to bust out Forky from the antique store goes horribly wrong, with Buzz, Bo Peep, and the others deeming the situation too dangerous to attempt again. Woody vehemently disagrees, and tells them so. While his judgment is frequently clouded, the perspective of a friend always helps Woody find his center, apologize, and make things right.

Toys reveal themselves to animals

While there is a strict, unspoken rule among toys to never reveal themselves to humans, this doesn't seem to apply to animals. The toys openly behave as living beings in front of dogs and cats throughout every "Toy Story" movie.

Sid's dog, Scud, threatens Woody and Buzz's chances of making it back to Andy in the first "Toy Story." The dog chases them down the street, and the toys' madcap escape ultimately ends with the animal trapped, but safe, as a car wreck blocks him from pursuing them any further. "Toy Story 2" and "Toy Story 3" both involve Woody enlisting the aid of Andy's dog, Buster, to help Woody inconspicuously travel from Andy's room to the front yard. The lengthy time gap between those two movies, though, means that Buster ages quite a bit between appearances.

By "Toy Story 3," he's older and not quite as spry in his ability to maneuver Woody around the house. "Toy Story 4" breaks tradition, but only slightly, by featuring a cat instead of a dog. Pet of the antique store owner, the feline goes wild as Woody and the others attempt to rescue Forky. The cat even swallows Giggle McDimples, only to cough her up a few minutes later.

When all is said and done, it's hit or miss whether animals are helpful or traumatizing for toys, but the good must outweigh the bad, as the playthings to continue to let themselves be seen by them.

A schtick for Buzz

Constantly discovering new layers of himself is Buzz's ongoing character journey in every "Toy Story" movie. With comedian Tim Allen as Buzz's voice actor, Pixar writers provide fresh, funny material with each new adventure. Interestingly, each installment's "Buzz schtick," if we were to call it that, stays contained within its film and doesn't spill over into any other entries in the series.

The comedy of Buzz in the first "Toy Story" comes in him believing he's really the character his toy depicts: Space Ranger Buzz Lightyear, hero of the galaxy. Before this plot point becomes a dramatic philosophical conundrum, it lends itself to some hilarious moments as Buzz approaches mundane life with the attitude of an interplanetary hero. "Toy Story 2" has Buzz meet his double, a newer, shinier model of the toy with an advanced utility belt, who also happens to believe he's a Space Ranger. Buzz spends the movie trying to settle things with his twin while also evading a toy of Zurg, known in the Buzz Lightyear universe as a "sworn enemy of the Galactic Alliance."

The toys accidentally activate Buzz's Spanish mode in "Toy Story 3," making him emulate the language and movements of a romanticized Spanish flamenco dancer. Lastly, in "Toy Story 4," Buzz makes a habit of letting his "inner voice" guide him, which really just means he's allowing his toy's built-in catchphrases to advise his actions like a magic 8-ball.

Playtime

Given that the entire series revolves around kids' relationships with their toys, at least one scene in every "Toy Story" movie naturally showcases playtime, from the imaginative to the rough and tough.

In fact, playtime is the very first thing we see in the entire "Toy Story" series, as Andy plays make-believe with his toys in the style of a classic Western. His next door neighbor, Sid, is equally creative in a completely different way, using playtime as an opportunity to pretend he works in a number of occupations — from doctor to rocket launcher — that mutilate, disfigure, or altogether explode toys. "Toy Story 2" has Andy casting his toys in an adventure facing off against the evil Dr. Porkchop, a role he's cast for Hamm, and in "Toy Story 3," Pixar even uses animation as what Andy imagines in his head rather than what's actually happening in his room.

"Toy Story 3" also shows how toddlers at the daycare completely wreck havoc in their playroom, but ends on a gentler note with Andy giving the toys over to Bonnie and having one last playtime with them. Like Andy, Bonnie has a vivid imagination and comes up with fantastical scenarios for her toys, which continues in "Toy Story 4." Unlike Andy, though, Bonnie casts herself as an active character within the stories she creates while playing with her toys. She participates in the world within her mind right alongside them, whether saving a haunted bakery or opening a hat shop.

Animation advances

The original "Toy Story" debuted in 1995 as the world's first computer-animated feature film, while "Toy Story 4" was released in 2019. Within the elapsed 24 years, we can track leaps of technological advancement in animation as the series progresses.

For starters, take a look at the humans. While perhaps advanced for the time, Andy and his mom look rather startling in "Toy Story" in comparison to their more detailed renderings in "Toy Story 4." The look of everything just gets better and better with each successive film. The stitching of the individual threads of Woody's checkered shirt becomes more pronounced. The dents and smudges evident on the toys' surfaces from years of active playtime become visible. The result is each "Toy Story" movie being a more complex work of art than the last, with each of them retaining a charm that embodies the era in which they were created.

Just creating a full-length computer-animated film would have been unachievable a few years prior to the production of "Toy Story." Likewise, its sequel's impressive space-adventure opening would have been a tall order for its predecessor. The third installment's dappling trees in the sunlight of Bonnie's yard would have looked cruder had they been shown in the second film. The fourth movie's rainstorm might have been avoided had it been suggested for the third entry. Each Pixar film leaps forward technologically, and that's evident with a series that's been going strong for over two decades.