Everything Elvis Gets Wrong About The True Story

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

No one's life story can be fully told in a two-and-a-half-hour movie, especially not a life as remarkable as Elvis Presley's. The Tupelo, Mississippi-born singer became a worldwide superstar at age 19 and remains one of the 20th century's most enduring icons; 45 years after his death at age 42, Presley is still among the highest-earning celebrities of all time. His life has been written about dozens of times in films, television shows, books, podcasts, and in the hip-swivels of countless Elvis impersonators. Depending on the telling, Presley is a symbol of rebellion against post-war puritanism, a cautionary tale about the ravages of addiction, or the ultimate example of racial appropriation.

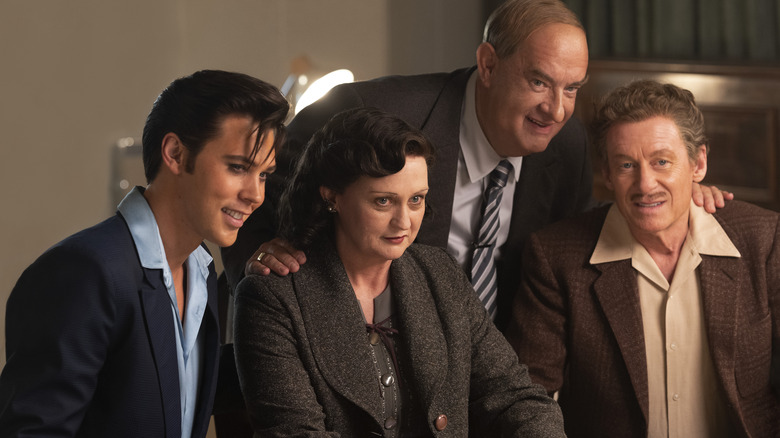

In 2022, "Moulin Rouge!" and "The Great Gatsby" director Baz Luhrmann released "Elvis," a high octane birth-to-death-and-beyond re-imagining of The King of Rock and Roll (Austin Butler), told through the eyes of his scheming, infamous manager Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks). As with Luhrmann's dizzying trips to 1890s Paris and 1920s New York, "Elvis" plays fast and loose, using maximalist style and anachronistic elements to convey the jolt of energy Presley brought to 1950s America. The broad strokes of Presley's life, from Memphis to Hollywood to Vegas, are presented more or less as they happened. But several elements of the film stray from real life, either for dramatic effect or to further Luhrmann's own theories about what Elvis represents in the 21st century. Let's look at what "Elvis" gets wrong about the true story.

Hank Snow

As the film begins, Elvis has already cut his first hit record, "That's All Right, Mama," but it's his appearance on the syndicated country music radio show "Louisiana Hayride" that makes him a star and brings him to the attention of former carnival barker turned music promoter Colonel Tom Parker. The headliner on "Hayride" is longtime country star Hank Snow (Luhrmann regular David Wenham), who is aghast at the way Presley gyrates in front of the crowd. Later, when Parker convinces Elvis to strike out on his own, Snow seems all too eager to see the young man gone.

Snow's reaction works as a symbol of how the musical establishment of the day was threatened by Presley specifically and rock and roll in general, but in real life Snow was no prude. Both he and Parker saw the moneymaking potential in Elvis early on, and the two in fact co-managed Presley's career for a short time. As his son Jimmie Rodgers Snow noted years later, Snow had every financial reason to make Elvis as successful as possible, even allowing Elvis to close out their shows.

Snow's exit from the Elvis Presley story in real life came at the hands of Parker, who, according to biographer James Dickerson, used Snow to sweet-talk Presley's family into signing a new contract before cheating Snow out of his share. "Hank Snow said that Parker was the lowest human being that had ever walked the Earth," Dickerson told the New York Post in June 2022.

Elvis Presley Enterprises

The contract that in real life cheated Hank Snow out of managing Presley's career is presented in the film as a kind of deal with the devil, as Parker pours honey into the ears of Elvis' parents Gladys (Helen Thomson) and Vernon (Richard Roxburgh). Parker at this point has already masterminded Presley's move from the regional Sun Records to major label RCA-Victor, and he solidifies his control over the entire family by having them sign into existence a new business called Elvis Presley Enterprises, of which Vernon (who had been jailed for check forgery when Elvis was a boy) would be business manager. Gladys is skeptical of the Colonel, and would remain so up until her death in 1958, but signs the contract anyway when Parker coos about Elvis having the strength of two men — a knowing reference to Elvis' stillborn twin brother Jesse.

Parker did indeed have Elvis and his family under contract, and Vernon was indeed manager of Elvis' personal business (and would later be executor of his estate). But the business venture known as Elvis Presley Enterprises (or EPE) wouldn't be formed until after Presley's death. EPE was founded by Vernon, the Presleys' longtime accountant Joseph Hanks (no relation to Tom), and Elvis' ex-wife Priscilla as a way to preserve and manage his estate. EPE opened Graceland for tours in 1982 and over the years has developed the area around the home into a shopping destination, concert venue, and resort.

Elvis and the King

One of the most controversial aspects of Presley's life and legacy is his relationship with blues music and southern African-American culture in general. Luhrmann's film clearly states that Elvis' use of Black music and culture was appreciation, not appropriation, and works hard to convey that Presley came by his love of blues and gospel sincerely. Flashbacks show a young Elvis feeling the spirit in a Black Pentecostal church in Mississippi, while the scenes of his early days in Memphis show him on Beale Street, surrounded by the sounds of Black contemporaries like Little Richard, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and Big Mama Thornton, whose hit song "Hound Dog" would become one of Elvis' signature tunes.

The film also gives him a friendship with blues legend B.B. King (Kelvin Harrison, Jr.), already a well-known musician and DJ at the time, who views Presley's fame with a certain wry detachment. According to biographer Alanna Nash, however, this relationship seems to have been extrapolated from a famous photograph of the two men together backstage at a Memphis charity show that King was headlining. Presley did not play at the show, but appeared briefly on stage at the request of emcee Rufus Thomas and gave the crowd a little leg shake. In real life King appears to have been fond of Presley on a personal level, if ambivalent about the success Elvis and other white artists had adapting Black music, but there is no evidence that the two had a friendship like what the film portrays.

Uppers and downers

The extent of Presley's addiction to prescription drugs wouldn't come to light until after his untimely death at age 42, of a heart attack that was likely caused by his persistent substance abuse. His reliance on amphetamines (or "uppers") to keep up with his daunting tour schedule and barbiturates ("downers") to help him sleep, especially in the last decade of his life, is now well-documented, but it's never been confirmed exactly how early in his career his drug use began. "Elvis" establishes that the pill habit began on Presley's very first backwoods tour in 1955. One scene has Elvis in the car with his band, fighting to stay awake. Bass player Bill Black (Adam Dunn) offers a white pill to Presley, claiming it will put "some pep in your step."

Many theories about the origin of Elvis' addiction have been shared over the years. In 1979 the New York Times quoted anonymous sources speculating that Presley's pill habit began in the 1950s, possibly due to Presley's religious aversion to alcohol and his feeling that prescription drugs were more "legitimate" than street narcotics. Another rumor is that he was snatching his mother's diet pills long before that. According to Presley biographer Peter Guralnick (via the Washington Post), it was a fellow soldier who introduced him to amphetamines during his two-year stint in the Army from 1958 to 1960. Whatever the truth may be, there seems to be no evidence that Black was his first supplier in real life.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Don't change, Elvis!

In just a few short years at the end of the 1950s, Presley went from transgressive provocateur to clean-cut all-American family entertainer. In the film, this is orchestrated by Parker against Elvis' will, starting with a humiliating performance on "The Steve Allen Show" where he performs "Hound Dog" with an actual dog on stage. Protesters line the streets outside Graceland waving signs that read "Don't Change, Elvis!" and "We Want the Old Elvis Back!" At a pivotal show at the Memphis Fairgrounds, after being warned against wiggling by both the Memphis police and Parker, Elvis' performance is so intense that it causes a riot. Elvis is taken away in a police car and is threatened with either a stint in the Army or in jail.

While the "Steve Allen" performance is based on a true story, the Memphis fairground riot is a composite of several different concerts, most notably one in Jacksonville, Florida where a local judge warned Presley against any lewd behavior. But the film gives the impression that Parker neutered Elvis' image under the threat of blackmail from shadowy establishment forces, which according to Alanna Nash is ridiculous. Parker welcomed any and all controversy as good publicity. The Army stint was indeed meant to give Presley a more family-friendly image, but for a much simpler reason: career longevity. "Neither Elvis nor Parker thought rock and roll would last," Nash told Variety. "Elvis, especially, thought that it might even be over by the time he got out [of the Army]."

Priscilla and Elvis

Priscilla Presley has long been the public face of her ex-husband's legacy, serving as a producer and/or consultant on many of the films made about Elvis' life, running EPE for years, opening up Graceland for tours in 1983, writing a tell-all memoir about their turbulent relationship, and in general being available to talk about Elvis any time, anywhere. It's a little surprising, then, how little she figures into Luhrmann's film. Priscilla as a character, played by Australian actress Olivia DeJonge, has just three major scenes: Elvis and Priscilla's courtship when he's stationed in Germany, the moment in 1972 when his infidelities and drug use become too much to handle and she leaves, and a final conversation in 1975, as Elvis, on the downslope of his career, worries aloud that he has accomplished nothing in his life.

The film's inaccuracies when it comes to Priscilla are for the most part sins of omission. The film leaves out the damning detail that she was just 14 years old, 10 years his junior, when she and Elvis met, or that after leaving the Army Presley arranged for Priscilla to live with him at Graceland and complete high school in Memphis. The film also omits the bizarre episode late in their marriage when Priscilla had an affair with her martial arts instructor Mike Stone, who Elvis reportedly considered having killed.

Memphis is burning

From 1956 to 1969 Presley starred in over 30 Hollywood movies; his film work, both as an actor and as a singer, dominated his career for the bulk of the '60s, which Baz Luhrmann glides over via a zippy montage. The film seems to believe that Elvis' Hollywood years were filled with hokey kitsch that bears little resemblance to the transgressive, inherently political artist he was at heart. In 1968, however, his conscience is stirred by the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April and Robert F. Kennedy in June. After King's assassination in Memphis, both Priscilla and Presley's bodyguard Jerry Schilling (Luke Bracey) feel that Presley should release a statement; "Memphis is burning," Priscilla implores.

While King's murder sparked riots and violence in major cities across the country, the public reaction in Memphis was more muted. As author Hampton Sides wrote in the 2010 book "Hellhound On His Trail" about King's murderer James Earl Ray, the first night in Memphis after the murder had isolated incidents of violence and looting, including the police shooting of a 26-year-old Black man. But where the riots in other cities lasted nearly two weeks after King's death, Memphis fell into an eerie calm, or perhaps a deep mourning, such that King's widow Coretta Scott King was able to safely visit the city four days later to continue his work with the Memphis sanitation workers' strike.

The comeback special

When Robert Kennedy's assassination occurs in June 1968, Elvis and company are in the midst of filming a television concert special. Colonel Tom Parker has explicitly sold the show to NBC as a Christmas special to be aired in December, forcing Elvis to wear ugly sweaters and constructing an elaborate North Pole set for him to perform on. Elvis and the special's director, Steve Binder (Dacre Montgomery), have different plans however. Elvis wants to use the special to get back to his down and dirty rock and roll roots and chart a new way forward in his career. Against the Colonel's wishes, they ditch the sweater for a black leather jumpsuit and forget about the North Pole. The resulting concert film, commonly known as the '68 "Comeback Special," is a smash hit and latter-day triumph for The King.

Much like the last time that Presley and Parker clash over the direction of his career, this dynamic is largely invented for the film. In real life, according to biographer Alanna Nash (via Variety), the special was never meant to be a Christmas special, other than by virtue of airing in December. "There was never a Christmas sweater or fairy-tale Christmas set. That's Luhrmann being a showman." Likewise, the idea that Presley and Binder would rebel against Parker in the midst of filming is not terribly realistic to either Elvis' relationship with Parker or how producing a television show works.

Death threats

After the success of the 1968 "Comeback Special," Presley is riding high and dreaming big. He announces plans to finally tour the world, but first Parker books him into a weeks-long gig at the brand new Hilton International Hotel in Las Vegas. The Vegas residency is a huge hit and gets extended. Presley continues to plan his global tour, but Parker has grave concerns about securing Elvis' safety overseas, especially once startling death threats start showing up in the mail.

What Presley doesn't know, however, is that Parker is purposely delaying the start of the international tour because he is an illegal immigrant and fears being deported if he ever leaves the country. The film heavily suggests that the death threats against Presley were staged by Parker in order to support his bogus security concerns.

We may never know if some of those death threats were forgeries by Colonel Tom, but thanks to the FBI, we know that many of them were in fact real. From his earliest days on the national scene, the FBI kept careful tabs on Elvis and his activities, as director J. Edgar Hoover feared that he might be a corrupting influence on the nation's youth. The FBI's extensive file on Presley contains a death threat sent through the mail in 1956, as well as confirmations of threats made to Presley and his associates in the 1970s.

Colonel Tom fired on stage

After years of languishing in Las Vegas while his dream of touring the world gets pushed further into the distance, things finally come to a head between Presley and Parker in 1974. An anonymous letter sent to Jerry Schilling has revealed the truth about Parker at last: His Dutch birth, his illegal status, and the fact that he in essence sold Elvis to the International Hotel in exchange for unlimited credit on the casino floor. An overcome Elvis collapses backstage before a show; he is given a shot of amphetamines to revive him at Parker's command. On stage in the middle of the performance, an inebriated, slurring Elvis introduces Parker to the crowd warmly (as we'd seen him do in an earlier scene), but then turns cold and sarcastic. In a loud, dramatic turn he fires Parker in full view of the audience.

There is a larger inaccuracy at play in this scene that we'll address later, but to begin: This never happened. There was an incident that year in which Presley made disparaging remarks on stage toward hotel owner Barron Hilton, who had fired one of Presley's favorite hotel employees. That resulted in he and Parker getting into a shouting match backstage and nearly dissolving their relationship, but that is as close as real life ever got to matching the movie's onscreen meltdown. "Elvis would never have been so crass as to have fired Colonel from the stage," writer Alanna Nash said.

The mystery of Andreas Cornelius van Kuijk

The larger issue in the onstage firing scene, and the film as a whole, is what exactly Elvis — or anyone — knew about the true identity of Colonel Tom Parker. For decades he claimed to be a good old boy from Huntington, West Virginia who ran off to join the circus as a youth, which is where he picked up an ever-so-slight European accent. Despite making enemies left and right in the music business (such as former client Hank Snow), no one seemed to mind terribly where this carnival barker came from, as long as the money kept rolling in.

"Elvis" is told from Parker's perspective, and weighted by the revelations about his life that only came to light after Presley's death. It wasn't until the early 1980s that it became widely known that Parker was actually Andreas Cornelius van Kuijk, a Dutch immigrant who had briefly served in the U.S. Army but had never become a naturalized citizen. He fled from the Netherlands in 1929, possibly after being implicated in the murder of a woman named Anna van den Enden, and he still had family in Europe that he had broken all contact with. The filmmakers know all of these things, and to an extent they assume that the audience does as well, which is perhaps why Tom Hanks affects a thick Dutch accent so pronounced that no one, not even a credulous kid from Mississippi, would have ever bought that he was just a West Virginia hillbilly.