Horror Films That Were Ruined By Revealing Too Much

The genre of horror is rooted in the unknown. It's what makes a scary movie scary to begin with. We don't know what lurks behind the closet door. Nobody can figure out why all of the children in town are acting strange. That guy with the machete and hockey mask that just killed your best friend? Okay, yeah, that's scary, but why did he do it and where did he come from? But it's a double-edged sword.

Fear in horror stems from questions, but the answers paradoxically make that fear vanish. Recent films like The Babadook and It Follows have struck this balance between questions and answers perfectly and been acclaimed for it. It's like a magic trick. The thrill is in being fooled. In fact, revealing too much can ultimately make a movie less effective, and sometimes downright bad.

The House on Willow Street (2017)

Nothing ruins an innovative premise like contrived exposition, and The House on Willow Street falls victim to this around the middle of its second act. It's a shame, because the film's concept is extremely cool. A gang of somewhat hapless criminals kidnaps the daughter of a rich family intending to hold her for ransom. But they quickly realize that something is off about her. When they discover that her parents have been brutally murdered, it becomes clear that the daughter is responsible and that she may be possessed by some otherworldly force.

Unfortunately the momentum built up by this premise grinds to a screeching halt when halfway through the film the criminals conveniently stumble across information explaining in explicit detail what's going on: the daughter is possessed by a demon with a very specific goal and a very specific set of weaknesses.

From there on out it goes from cool indie horror flick to something resembling a bad made-for-TV movie, right down to the lousy special effects. Had the details been kept more under wraps, the film could have salvaged its intriguing premise. Unfortunately, they aren't, and what could have been a great new horror movie is instead a landmark example of squandered potential.

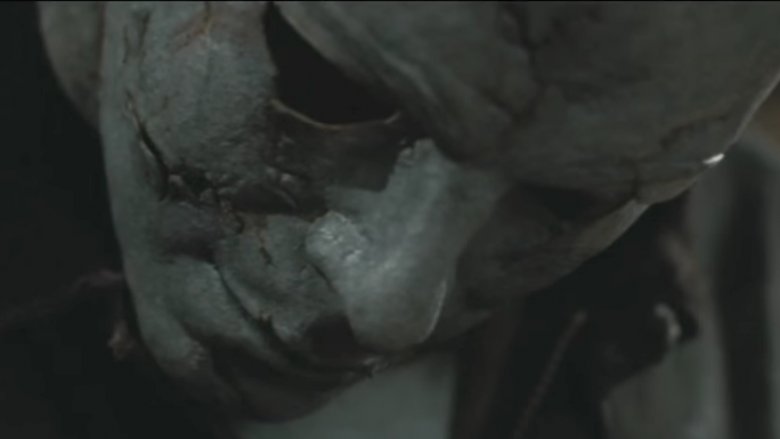

Mama (2013)

All things considered, Mama isn't too shabby as far as horror movies go. It's got a killer cast led by Jessica Chastain and everyone's favorite jerk with a heart of gold from Game of Thrones, Nikolai Coster-Waldau. Director Andy Muschietti does a perfectly solid job in his feature film debut (and clearly showed studios enough promise to be trusted with that killer clown movie everyone seems to love so much). And with the guiding hand of Guillermo del Toro, it should have had all the makings of a modern horror classic.

The problem? Once we actually get to see the titular Mama, it's a letdown, to put it mildly. The creature isn't actually all that scary at the end of the day. Sure, it has a misshapen face and contorts its body to all kinds of weird angles, but there's a lack of menace once Mama is actually revealed. Simply put, it might look weird, but it's nowhere near as scary as the buildup to its reveal is. Perfecting that balance between buildup and reveal can admittedly be difficult, and while the buildup in Mama is great, the reveal of the ghosts' design is ultimately a letdown. It damages the reputation of what could have been an otherwise great horror film.

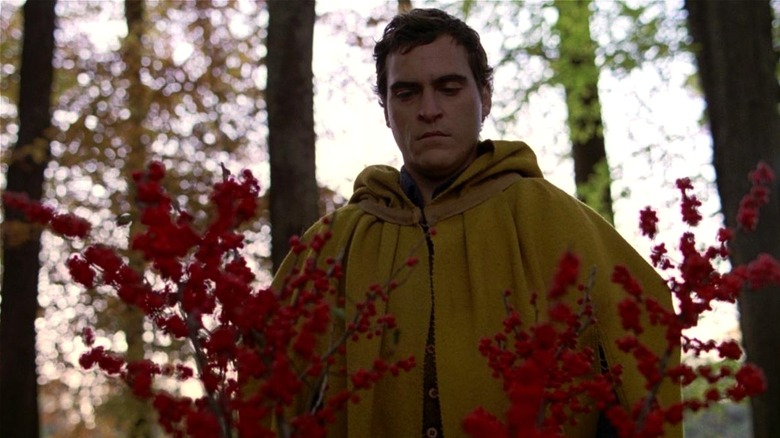

The Village (2004)

Generally, a plot twist improves the overall quality of a movie, turning already-good movies into great ones. But then there's the other end of the spectrum, which is where you'll find M. Night Shyamalan's The Village. It's a film that sharply diverts from the story it purports itself as telling, that being the tale of a village in the 1800s terrorized by a race of creatures living in the forest surrounding it. But as the film progresses, it's revealed that this is not the case. Not only are the creatures a fabrication created by the village elders, but the village in question actually exists in the present, acting as a sanctuary from the outside world constructed, again, by the village elders.

Is the twist bad in and of itself? No, but the execution of the twist does the film no favors. It creates a situation in which every single detail of the film's mysteries are revealed. And yes, mysteries do need answers in order for a film to be satisfying. But they don't need full-on exposition monologues delivered onscreen by the film's director (which, yes, happens in the movie courtesy of an M. Night Shyamalan cameo).

That degree of on-the-nose explanation pulls back the curtain entirely, leaving no ambiguity for the viewer to ruminate on. The Village is beautifully shot and very well-performed. But its ending reveal belongs in an episode of Scooby Doo, not a period-piece horror flick.

Halloween (2007)

The original Halloween worked as well as it did for...well, a ton of reasons, if we're being honest. But one of its most important traits is the way it handles the man who would become a horror icon, Michael Myers. While he doesn't go full-on Friday the 13th and make the identity of the killer a total mystery, original director John Carpenter knows what the audience needs to know about Myers and gives them exactly that, nothing more and nothing less.

The remake, directed by Rob Zombie, takes the opposite approach. Revealing the entirety of Michael's backstory fails to make him more compelling and actively makes the film less scary. Zombie already had an uphill battle to fight when it came to this facet of making the film. Fans going in likely knew plenty about Michael's backstory from previous Halloween films, making it difficult to make him as mysterious a character in the way that the original did.

But rather than find creative ways around that, Zombie leans entirely into making Halloween a full-on origin story for Michael Myers. It works to the detriment of both the film and the character. By the end of the film, we know far too much about Zombie's version of Michael to be nearly as scared of him as we could be.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning (2006)

If there's one character out of the slasher cinema rogue's gallery that doesn't need too much of a backstory, it's Leatherface. While the beginnings of characters like Freddy Krueger and Michael Myers both tie into how they became who they are in a way that's compelling for audience members and relate to the plot of their films, the beauty of the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre was that Leatherface didn't need that. He and his family are sadistic backwoods maniacs. That's really all you need to know. And the last thing a chainsaw-wielding-human-skin-wearing maniac needs is a sympathetic origin.

Unfortunately it seems that the filmmakers behind The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning thought otherwise. Not that horror origin movies have too stellar a track record, but The Beginning stands out as especially horrid among the flock. The film strips away Leatherface's menace and replaces it with a tragic origin in which everything from his parentage to his real name is spelt out in concrete detail.

Furthermore, there's an active effort to make him a tragic character — sympathetic, even. The film paints him as a victim of circumstance and a pawn in the evil schemes of his adoptive family, who are just as evil as he is. It fails entirely both as compelling fiction and as horror cinema. Origin stories may be easy money in any genre, but nobody going into a Texas Chainsaw movie needs or wants to feel sympathy for a psychopath with a skin mask.

Insidious: Chapter 2 (2013)

Horror sequels are tough, especially when they're the follow-up to a movie as wildly successful as James Wan's Insidious. Insidious: Chapter 2 isn't a total failure by any means, but it definitely falls victim to lifting away the curtain a bit more than it should. It builds on the original movie even more than your average horror sequel, directly following up on the events of the first and expanding on them and the world they established. The problem is that the events of the first movie didn't really need any further explanation.

Insidious was a great, fresh concept upon its original release and nothing makes something fresh seem stale like over-explaining it, taking away anything left for the viewers to ponder over. By elaborating on the experiences of Patrick Wilson's Josh as a boy in the Further and giving a direct origin to the phantom that has followed him for his entire life, Wan spells out what already made perfect sense.

Less is often more in horror films, and while the first film did a lot with very little, the second tries to do a lot with, well, a lot. It doesn't make for a bad movie per se, but it builds an entire cinematic world around simple concepts that might have been best left alone when Wan perhaps should have been doing what he does best: forging new ground.

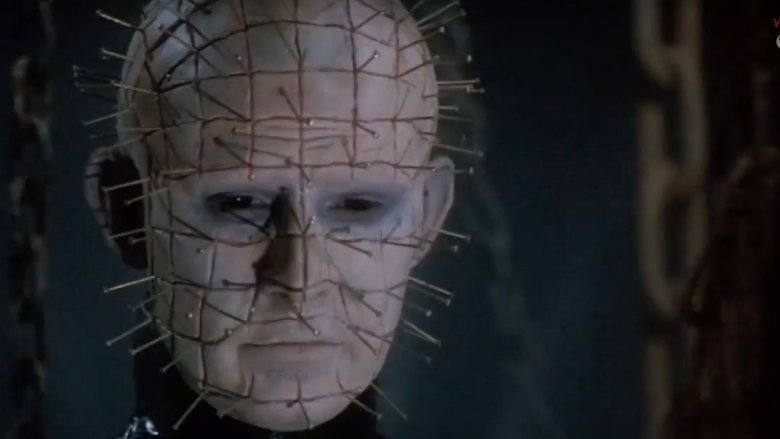

Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988)

No need to dance around this one: did anybody really need to see Pinhead's origin?

The original Hellraiser set up the Cenobite leader Pinhead as the Boba Fett of the horror genre. He's only onscreen for a short time, but he's so cool and compelling in that short appearance that he immediately became iconic. Giving him more screen time wouldn't necessarily damage or strip away his mystique, but Hellraiser 2 does everything it shouldn't with his expanded screen time, including outright revealing his origins. It reveals that he used to be human and depicts his encounter with the Lament Configuration, which turned him into Pinhead. It's one of the most egregious examples of a horror film revealing more than it needs to.

Pinhead, more than most horror movie villains, was perfect largely because of how little there was to know about him. What the audience is shown in the first film is more than enough for him to be effective as a villain. The viewer could extrapolate what they wanted from what they were shown and draw their own conclusions. Spelling out his origins as a human very nearly ruins everything that was great about him to begin with.

Don't Be Afraid of the Dark (2011)

There's a particularly common trope in the horror genre that even the best movies turn to sometimes: in order to figure out what's going on with whatever sinister force has invaded their lives, the protagonists turn to the local library, where either microfilm or a mysterious old book conveniently contains a massive exposition bomb telling them (and the viewer) everything they need to know to stay alive and defeat said sinister force. It's cliche, yes, but a movie isn't automatically bad for using it.

However, in the case of director and comic book artist Troy Nixey's remake of the 1973 film Don't Be Afraid of the Dark, it's handled especially poorly. The scene grinds the momentum of an otherwise pretty okay film to a halt and just reads as the filmmaker realizing it's time to spill the beans to the audience and let them know what's been going on.

And then there's the reveal as to what has been going on: tooth fairies? Admittedly, the film is a remake, so the content of the reveal is out of Nixey's control. But it's telling that the original feels far less guilty of overplaying its hand than the remake does, nor does its reveal slow the film's momentum. That the remake is only enjoyable up until this particular moment is a clear-cut instance of a reveal not being handled in a way that does any favors the film it's in.

A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987)

We're not saying "the son of 100 maniacs" isn't a great origin for a slasher movie villain. It's just that Freddy Krueger already had all the origin he needed. In fact, the original Nightmare on Elm Street struck the perfect balance between expanding on a horror villain's backstory and keeping it mysterious to a slight degree. Krueger's origin ties directly into the kids he's hunting but doesn't explain how his methods work or how to defeat him. It really is as perfect an origin as you can get.

And while Dream Warriors is actually one of the better Elm Street sequels, it gives even more backstory on Krueger that viewers don't need. Knowing about the tragedy of his conception just creates conflicting emotions about a character who's otherwise a pretty cut-and-dry villain. That he was conceived the way he was adds nothing to the character, and while it might not actively detriment Freddy's allure as a villain, it doesn't help it.

Viewers need horror villains to remain mysterious in some way or another, lest they become more familiar to them than the supposed protagonists of each sequel. By revealing more than necessary about Freddy's life, the Elm Street franchise took its first step down a path that would lead to Freddy being a comedian with knife hands that couldn't scare viewers if he tried.

Saw II (2005)

Admittedly, the blame for revealing too much about Jigsaw isn't entirely on Saw II. That easily falls just as much on the rest of the sequels in the Saw franchise. But Saw II was the first one to begin revealing far too much about its infamous villain to its fanbase.

It's sometimes easy to forget that in his original appearance, Jigsaw's identity was a twist ending. The man born John Kramer had been in the room with the protagonists the whole time posing as a dead body. It was a perfect moment for the character. Throughout the film his motivations are well-established, and through them we learn everything we need to know about the character. By the end, we get the slightest glimpse at his true identity, and it's done in a way that elevates everything we already know about the character. And it's what the audience needs to understand about a horror villain: motivation and method. Anything that doesn't tie into those is superfluous.

But Saw II gives him a tragic backstory and a concrete, fleshed-out identity. He's no longer a mysterious, faceless presence. He's just a man. A very smart one, but a man. And the information it gives us about him is redundant given that we already know why he does what he does to his victims. It just makes his story more concrete, more defined, and far less intriguing. A faceless killer is terrifying. A cancer patient with a backstory is not.