The Untold Truth Of The Matrix

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

When The Matrix debuted in March 1999, filmgoers knew they were seeing something important, even if they weren't sure exactly what. The film melded an incredibly heady sci-fi premise with Hong Kong-style kung fu action and bizarre special effects of the type that hadn't really been seen onscreen before, and word of mouth quickly spread about the film and its mysterious creators, the Wachowskis.

Of course, we now know the legacy of The Matrix—it's widely considered one of the greatest science fiction films of all time, and its surprise success spawned two sequels and other various media while profoundly influencing the sci-fi and action genres immediately thereafter and to this day. But in the early '90s, Hollywood had very little reason to take a chance on two untested and unconventional filmmakers with an idea for a film that—purely in conception—must have sounded completely insane. Let's take a closer look at how one of the most influential films of modern times made it to the screen, the untold truth of The Matrix.

It only exists because of a bad action movie

It's safe to say that The Matrix never would have come to be if not for one really crappy film: 1995's Assassins, a lazy action vehicle for Sylvester Stallone and Antonio Banderas, directed by Richard Donner in full paycheck-cashing mode. The Wachowskis' second completed script (their first, Carnivore, garnered them attention but was never produced), Assassins was optioned by legendary producer Dino De Laurentiis, who promptly sold it to Warner Bros. for five times what he paid. The Wachowskis' first real Hollywood experience didn't get any better from there: screenwriter Brian Helgeland (who would go on to write L.A. Confidential and Mystic River, among many others) was brought in to overhaul the script, doing so with all the subtlety of a jackhammer.

Lana Wachowski claimed that Helgeland's rewrite did away with "all the subtext, the visual metaphors... the idea that within our world there are moral pocket universes that operate differently." The Wachowskis even lobbied unsuccessfully to have their names removed from the credits, but it wasn't all bad: Assassins paid for a renovation of their parents' house, and earned the pair a deal with Warner Bros.

Their manager Lawrence Mattis remembered that "nobody got" The Matrix when he first sent out the script in 1994, saying that Warner bought it "half out of the relationship with [the Wachowskis] and half because they thought something was there." But once the deal was done, the filmmakers took steps to make sure that creative control wouldn't get away from them again.

The Wachowskis almost didn't direct

The Wachowskis had developed a relationship with Assassins producer Joel Silver, whom they showed their script for The Matrix early on. According to to Wired, he was immediately blown away. "The minute I started reading the script for The Matrix, I wanted to see it," he remembered, "but then the [Wachowskis] said, 'And we want to direct it.' That was going to be tough." Instead of taking a gamble on a script that was obviously going to take a beefy budget to realize, Silver took a more cautious approach: he greenlit Bound, a smaller piece about lesbian lovers on the run from the mob, which the Wachowskis would write and direct.

The conventional mythology is that this amounted to an audition, but Lana Wachowski disputes this, telling Buzzfeed that Silver "made that up." But the film, made on a tight $6 million budget, was a hit with critics (if not at the box office) and was almost enough to convince Warner Bros. to let the newly-minted directors proceed with their passion project. There was just one problem: while everyone seemed to agree that The Matrix was a great script, nobody understood the Wachowskis' vision in the least.

The storyboards were extensive

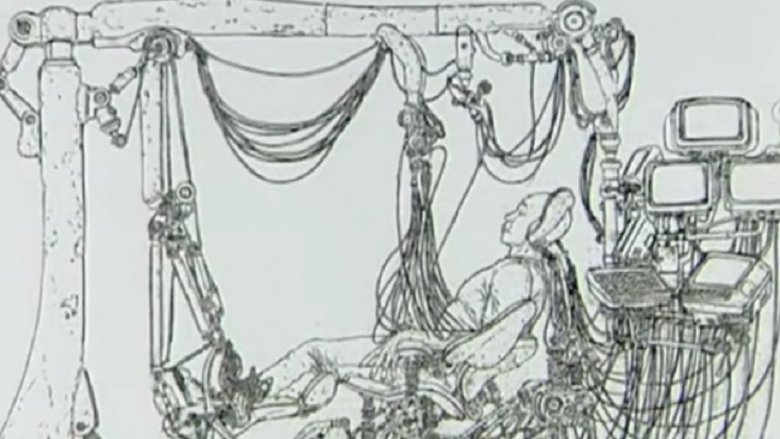

Lana Wachowski joked in the same Buzzfeed interview that producers were so confused by the premise of The Matrix that nobody understood why the heroes couldn't just blow the Matrix up "like the Death Star." Obviously, it was going to take more than words on the page to illustrate the Wachowskis' shared vision, so they sensibly turned to a pair of dynamic illustrators—Steve Skroce (who had worked for Marvel on Amazing Spider-Man and Gambit, among others) and Geof Darrow (best known for his work on the Frank Miller series Hard Boiled). Working in close conjunction with the Wachowskis and several additional artists over three months, the duo created storyboards and concept art that finally, decisively sold Warner Bros. on the project.

Skroce handled the storyboards, illustrating scenes in a dramatic, noir-like style with a heightened sense of motion and impact—over 600 individual illustrations were created. Darrow handled concept art and, for the first time, executives were able to visualize how this crazy script would translate to the screen.

It was enough for Warner Bros. to greenlight a $60 million budget for The Matrix, and it's easy to see why. Many of Skroce's bold illustrations are stunningly similar to shots in the finished film, and Darrow's detailed and elaborate concept art perfectly nails the film's visual aesthetic. The pre-production artwork was so impressive that it was collected in a hardcover volume, The Art of the Matrix, in 2000.

The entire cast was almost different

While the suits were now fully on board, it didn't mean they were ready to relinquish full creative control. The cast, in particular, would basically be decided by Warner Bros.—and it's not like the Wachowskis didn't have opinions of their own on the matter.

In a Matrix Fans interview with series composer Don Davis, it was revealed that the casting process was extensive and considered nearly every hot actor in Hollywood at the time. Davis asserts that Keanu Reeves was not the Wachowskis' first choice for the role of Neo—that would have been Johnny Depp—and that the studio wanted Brad Pitt, but he turned down the role, as did Val Kilmer and Will Smith. Neo's casting was eventually whittled down to a choice between Depp and Reeves (who Warner Bros. preferred) before Reeves was ultimately cast. Samuel L. Jackson was considered for the role of Morpheus, as was Gary Oldman—but the studio's choice was Sean Connery, who revealed that he was offered the role but turned it down, leading to the casting of Laurence Fishburne. For the supporting characters, all kinds of lesser-known names were considered, as the studio apparently wanted a less expensive supporting cast (Carrie-Anne Moss has stated that she had "no career" before she was cast as Trinity).

It's easy to imagine an alternate universe—perhaps one even more real than our own—where The Matrix had a completely different cast, but at least one alternate Neo has no regrets. Will Smith has said that he's glad he turned down the role, as Reeves ended up being "brilliant."

It was filmed on location in Australia

Even a couple decades ago, $60 million was a pretty modest budget for a large-scale sci-fi action movie. In order to maximize the production budget, the decision was made to shoot The Matrix on location and on sound stages in Sydney, Australia.

As producer Silver put it, "Filmmaking expertise, competitive costs and a great spirit of cooperation all enhanced Sydney's appeal." The city also offered another distinct advantage—its layout and multitude of architectural styles made it perfect for depicting the nameless, anonymous city where most of the action within the titular Matrix takes place.

As for the sets, a total of 30 were built, most of them for the more futuristic-looking settings such as the interior of Morpheus' ship, the Nebuchadnezzar. But the largest set stood in for a more mundane location—the government office building where the insane second act shootout takes place. The set took up an entire block and required a translight (a backdrop which is lit from behind to look totally realistic) roughly half the length of a football field and four stories high.

They didn't really gamble the movie's entire budget

It's an often-quoted piece of trivia that Warner Bros. initially budgeted the film at $10 million, which the Wachowskis realized would never be enough to bring their vision to life. So, in an incredibly bold gamble, the pair promptly spent the entire greenlit budget on the film's iconic opening scene to impress executives into forking over their entire requested amount of $60 million. It's a great story, but unfortunately it isn't true. Like most myths, however, it contains a kernel of truth.

On the DVD commentary for The Matrix, special effects supervisor John Gaeta discusses what really happened. The production had been scheduled for a 90-day shoot, and it became obvious at a certain point that it was falling significantly behind. Executives were growing frustrated, so the Wachowskis and Gaeta hatched a plan: over a weekend, they cleaned up the opening sequence and its visual effects, added in some temporary sound effects, and sent it to the studio to let them know just how production was coming.

According to Gaeta, the gambit worked: Warner Bros. immediately backed off, "and at that point, they totally supported the movie." The shoot ended up taking 118 days to complete—nearly a month longer than scheduled.

Fight choreography was straight from Hong Kong

The Wachowskis envisioned the fight scenes in The Matrix being heavy on fast-paced, close-quarters martial arts combat with elements of wire work, of the type normally seen in Hong Kong action epics. In order to accomplish this, they knew they would need expert help—so they decided to appeal directly to the world's foremost authority in martial arts choreography, Yuen Woo-ping, director of such classics as Drunken Master and the man who made Jackie Chan a star. Of course, the master wasn't particularly receptive at first.

Speaking on a DVD featurette, Yuen remembers, "I really don't know how they got my number... [I] got a call from Hong Kong saying that these two brothers were really interested in talking to [me]," but he felt he was too busy at the time to take on the project. The Wachowskis fell back on a reliable ploy to change his mind—they sent him the script, and unlike Warner Bros. executives, Yuen "got it" immediately.

He agreed to bring his crew of trainers to the production, where his work began months before cameras ever started rolling—to the initial dismay of the cast, who may not have known quite what they were in for.

The leads spent months training

The decision was made early on that the actors would perform their own stunts, but they weren't exactly chosen for their extreme physical fitness or knowledge of martial arts. In order to accomplish the film's fight scenes, Reeves, Moss, Fishburne, and Hugo Weaving (Agent Smith) were subjected to an absolutely brutal training regimen that would have tested even seasoned professional athletes.

Speaking on the DVD featurette, Fishburne remembers, "We started training in October of '97, trained all the way through 'til March of '98. That was on, like, an everyday basis." Weaving adds, "It was a very involving, exhausting process... I initially thought we were going to be doing kung fu for maybe four or five weeks, something like that. It ended up being months and months of training."

Yuen related that it was his challenge to make these rank novices look like they'd been performing these maneuvers all their lives, and injuries to Reeves (neck) and Weaving (leg) further complicated the process. The cast also received a crash course in Hong Kong-style wire work, in which stunt crews use special harnesses connected to wires—which are digitally erased in post-production—to assist actors in performing superhuman leaps and flips of the type seen in the film. Weaving said of Yuen and his team, "Initially, I think [they] took us on and saw we were useless, which we were, hopeless at kung fu. But they slowly realized after a couple of weeks that maybe we were going to be able to get to a level where we'd be halfway decent."

A new photography technique was invented for "bullet time"

One of the most memorable and readily identifiable contributions made by The Matrix to popular culture required a completely new photography technique to achieve onscreen. It's the effect known as "bullet time," and although it's been referenced, imitated, and parodied a million times in the years since, it was absolutely stunning in 1999—because no effect quite like it had ever been seen before. "Bullet time" creates the effect of a shot moving into extreme slow motion—slow enough to track the trajectory of whizzing bullets—while the camera appears to pan around or track the events at a normal speed.

Effects supervisor Gaeta had two specific influences in creating the concept—the Japanese film Akira and director Michel Gondry. Speaking to Empire magazine, Gaeta said, "His music videos experimented with a different type of technique called view-morphing... our technique was significantly different because we built it to move around objects that were themselves in motion... rather than the static action in Gondry's music videos with limited camera moves."

This was accomplished with a special set constructed completely from green screen, into which a circular array of 120 still cameras and two motion cameras was built. Each sequence that employed the technique was first digitally simulated, then meticulously staged with the camera array programmed to shoot in a specific sequence with precise timing. While there's nothing keeping all those ripoffs and "homages" from copying the technique, they have to call it something else—the phrase "bullet time" is a registered trademark of Warner Bros.

It shares sets with a strangely similar film

When The Matrix began production at Fox Studios in Sydney, another production had just wrapped up work—Dark City, which was released in 1998 and has been noted as being very similar to The Matrix in some of its themes, as well as its visual design. At least the latter is no accident; some of Dark City's sets, including the rooftops over which Trinity makes her initial escape from the Agents, were re-used for The Matrix.

Among the first to note the thematic similarities between the two films was the great Roger Ebert, who gave The Matrix a moderately favorable review while all but accusing it of ripping off the earlier film—highly unlikely, since the Wachowskis' script was completed long before 1998. But Ebert never fully let go of this notion, consistently comparing The Matrix unfavorably to Dark City, which he considered to be one of the greatest films of its time.

In a 2005 retrospective, he made his feelings clear: "[Dark City] preceded The Matrix by a year... and on a smaller budget, with special effects that owe as much to imagination as to technology, did what The Matrix wanted to do, earlier and with more feeling."