How Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory Differs From The Book

Roald Dahl's children's books, with their unique mixture of bleakness, absurdity, and innocent positivity, pose a challenge to adapt to film. Dahl's work toes the line between the kaleidoscopic whimsy of childhood and the terror of a grotesque world that's beyond a child's comprehension; deeply tragic backstories and villainous adults are as common as magical creatures and fantastic scenarios. This is one reason that, despite several Dahl adaptations that followed it, 1971's "Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory" is the most iconic and enduring version of one of Dahl's books, enjoying decades of revered status on television and home video.

Even though Dahl himself reportedly disliked Gene Wilder as Willy Wonka and the film's overall sentimental tone, the movie holds a place in our culture that was in no way threatened by the 2005 Tim Burton/Johnny Depp remake, and it will likely outlast any subsequent versions, as well. However, while Mel Stuart's film mixes musical numbers, impeccably colorful design, and a brilliantly mad lead performance from Wilder to capture something largely true to Dahl's vision, it also takes plenty of liberties with its source material, up to and including a tweak to the original title. Here are all the ways "Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory" differs from the book.

Whose chocolate factory is it, anyway?

The first immediately noticeable difference between book and film is the swapping out of the book's title, "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory" for the film's title, "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory." Different reasons have been cited for the change — Paramount claimed it was done to emphasize Wonka over Charlie, but Mel Stuart later claimed that the name "Charlie" had some unfortunate racially-loaded subtext in 1971 that he wanted to avoid. Or might have just been for corporate synergy, as the Quaker Oats Company was financing the film and preparing to make their own "Willy Wonka" chocolate bars. But whatever the reason, the title does reflect a general de-emphasis on Charlie in the narrative, which results in Gene Wilder's Wonka really stealing the show.

Charlie is still the focal point and hero, but where he's in just about every scene of the book, the first 45 minutes of "Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory" cut away to the other Golden Ticket winners, to the news media, and to various one-scene gags depicting the global Golden Ticket frenzy. And once the tour of the titular chocolate factory starts, it's Wonka's show, as Wilder gets a mixture of lines from the book and new verbal tics and habits invented for the movie, while Peter Ostrum's Charlie is pretty much the same earnest, simple character he is on the page.

Charlie's family is less absurdly poor

Roald Dahl's depiction of the Bucket family is downright Dickensian. Out of the family's seven members, only Charlie's father is gainfully employed, and early on in the book he loses his job and the whole lot of them become stretched thin and gaunt from hunger. It's a bleak, harsh situation that the movie mostly just feints at without having the stomach to actually tackle.

The film does decide to kill off Charlie's father off-screen before the opening scene, adding a maudlin backstory element, but Charlie and his mother both bring in income as a paper boy and laundry worker, respectively. The family has to eat cabbage stew, but they seem generally rosy-cheeked and healthy, and they even have a couple of extravagances the book Buckets would never dream of — they watch the news on a small television, and they've knit Charlie a nice red scarf for his birthday in addition to his annual candy bar. In making the Buckets' situation slightly more palatable, the satire of the gluttonous Augustus Gloop or the wealthy and entitled Veruca Salt gets slightly softened in turn.

Singing: not just for Oompa Loompas

As if the process of merely adapting the book wasn't enough of a challenge, "Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory" is also a musical, meaning several more characters get to sing than in the book, which only features four long, somewhat preachy songs from the Oompa Loompas. Wonka's "Pure Imagination" is the most memorable, but the candy store owner's rendition of "The Candy Man" and Veruca Salt's "I Want It Now" are also iconic bangers.

Ultimately, the scattered songs don't really amount to much in the way of advancing the plot or any character development and seem artificially inserted into the narrative. Charlie himself doesn't even get a song, and the only ones that have any real meaning are the short, one-minute versions of the Oompa Loompa songs, which, just like in the book, are presented as morality lessons after each non-Charlie child has been undone by their own impulses.

The electronic media plays a bigger role

In the book, the pitifully poor Bucket family have only the newspaper to keep them updated on the first four Golden Tickets being found. It's implied that there are dozens of reporters swarming each child, but only in the movie adaption do we get a true sense of the media frenzy and global hysteria surrounding Willy Wonka's opening of the factory. Several different news broadcasts are interwoven with one another as the Buckets glue themselves to the news, and pedestrians huddle around TVs in shop windows and rush to get the newspaper from the newsstand.

The movie also cuts away to completely new characters that are only around for ticket-centric gag scenes. A woman hesitates to hand over her case of Wonka bars for her husband's ransom, and Queen Elizabeth herself shows up to the auction of the last case in the UK. "Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory" takes full advantage of the visual medium to hype up the idea of the mythical chocolate factory, depicting a hyperbolic fervor that the book can only hint at. It's one of the more effective sequences that's entirely unique to the film.

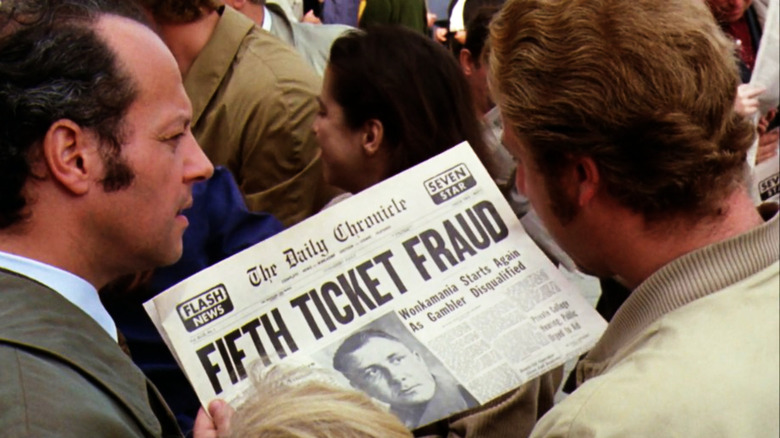

The fifth ticket hoax

One story beat that's added for the movie version is the fake-out involving the fifth Golden Ticket. At first it's reported to have been found in Paraguay, but within a day or so, this is revealed to be a hoax. The subplot is brief, but it adds a crucial element to the character of Charlie, who finds money in a sewer grate and uses it to buy two Wonka bars, the second of which turns out to have the real ticket. Even without the possibility of the Golden Ticket, and after being in tears the night before when the last one is allegedly found, Charlie still loves chocolate and Wonka products.

The movie may have been looking for a way to make the scene as touching as it is in the book, in which there's no hoax and Charlie finds the money when his family is even poorer than normal, buying two chocolate bars impulsively when he knows he should save the money for food. With less desperate of a protagonist, the film found a different way to give the magical moment when Charlie strikes gold its own subtext.

The Oompa Loompas are different

The most memorable images from "Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory," beyond Wonka himself, perhaps, are the unforgettable orange faces and green hair of the Oompa Loompas. They're significantly different than their book counterparts. The book's Oompa Loompas are "no larger than medium-sized dolls," and are frequently laughing and beating drums. In the movie they're taller, wear matching outfits, and are reserved and quiet when they're not singing.

They serve the same function in both stories, which is to delightfully roast each of the children after they break the rules and succumb to their terrible fates. In the movie, they keep each song to about a minute, with a dozen or so lines each, but Dahl's Oompa Loompas go on for pages and pages at a time, really driving home Dahl's distaste for gluttony, gum-chewing, greed, and tv-watching, in what are basically four long editorials snuck into a children's book in verse form. It's to the movie's credit that it bullet-pointed these diatribes into four catchy, succinct numbers.

Willy Wonka is significantly more terrifying

In a performance truly for the ages, Gene Wilder brings an astonishing number of different textures to Willy Wonka. He's warm and open-hearted at times, casually dismissive at others, and downright mean for one memorable moment at the end of the movie. But in his delight in (more or less) torturing his guests, he brings a level of malevolence and straight-up terror to the character that the goofier, bouncier book version of Willy Wonka doesn't quite have.

Wilder apparently demanded that he be allowed to perform the slow, seemingly crippled walk that Wonka does when his character is introduced, only to reveal with a somersault that he's energetic and spry, so it would never be clear whether or not he's lying from that point on. His face flashes with a transfixed sort of glee when terrible things befall his child guests, and he takes the tour group on a route seemingly designed to disorient them. Book Willy Wonka is like a chaotic but friendly cartoon character — Wilder's Wonka is all but a sociopath, an overgrown child that delights in his complete control over his strange and unsettling domain.

The boat ride becomes a true nightmare

In "Charlie & The Chocolate Factory," the boat ride to the Inventing Room is a two-page affair in which the Oompa Loompas row the boat frighteningly fast along a normal-looking tunnel, and Willy Wonka laughs while reciting a rhyme about it. "There's no earthly way of knowing / Which direction they are going..." Wonka sings. Then he turns on the lights before eventually stopping the boat. It's unsettling, kind of — the other parents all start calling Wonka crazy, though the Buckets are unphased — but more or less in line with his general vibe thus far, and pretty brief.

In the movie, the boat ride is a full-on bad mushroom trip freakout that more or less comes out of nowhere. Eerie red lights glow on Wonka's face as he begins the same rhyme, but with a calm, creepy tone to his voice that's far more terrifying than laughter. As images of death and animals devouring each other appear in flashes on the tunnel walls, Wilder starts to hysterically shout the final lines of the poem, making the entire sequence a crescendo of discomfort that's wildly different in tone from the book. If this is Willy Wonka's idea of a fun time, you can kind of see why he's never given tours before.

A fizzy lapse of character

One of the movie's strangest additions to the story is Charlie and Grandpa Joe's experience with the Fizzy Lifting Drink. Wonka mentions the new product briefly in the book, even including the fact that you have to burp to reverse the lifting effect, but no one attempts to drink it, and the group moves on. In the movie, Joe just blurts out "Let's take a drink Charlie, no one's watching!" to which Charlie enthusiastically agrees without even hesitating. Considering that Charlie's good behavior compared to the other children in the book is what earns him the chocolate factory in the end, this lapse in judgment is arguably the biggest departure the movie makes.

With this one scene, Charlie is essentially just as bad as the other children — he just manages not to get Ooompa-Loompa-ed off the premises because no one's around to see. When Wonka eventually finds out, it's only the act of returning the stolen Everlasting Gobstopper that puts Charlie back in Wonka's good graces. But considering how specifically the other children are faulted for their indulgences during the tour, this change really muddles the story's attempted lessons.

Geese are easier to train than squirrels

Veruca Salt's fate, and the room she meets it in, are the biggest changes to the story from a pure plot standpoint. In the book, she recklessly charges into the Nut Room, a room full of specially-trained squirrels that can crack walnuts whole without splitting them. As is her habit, she demands that she be allowed to have one, but they swarm her, tap on her head repeatedly "to see if she's a bad nut," and toss her down the garbage chute when they decide she is.

In 1971, neither CGI technology nor squirrel-training methods were up to the task of depicting the Nut Room as written, so the geese that lay golden eggs stand in for them instead. Geese, or at least puppets that look plausibly geese-like, sit high above scales that determine good eggs from bad eggs, and after a jaunty musical number, Veruca falls down the trash chute just the same. For the spoiled, rich Veruca, the geese are probably a more fitting instrument of her demise than the squirrels.

The mysterious Mr. Slugworth

A small but pivotal change from the book is the appearance of the enigmatic Mr. Slugworth, one of Wonka's rivals. Mentioned but never seen in the book, the film version first appears as a scar-faced man who approaches each Golden Ticket finder to whisper in their ear. He eventually asks Charlie to steal an Everlasting Gobstopper from the factory for him, which seems like a somewhat facile test — if any of the children wanted to get rich, they could just sell their Golden Tickets — but Slugworth turns out to be the key to Charlie's happy ending.

It's only when Charlie leaves behind his Everlasting Gobstopper that Wonka reveals the secret: Slugworth was actually his employee, testing the children for their loyalty, and Charlie is the only child that passed the test. As previously mentioned, the entire plotline detracts from the book's emphasis on the children's bad behavior, but since Charlie also slipped with the Fizzy Lifting Drink, the movie needed a way for him to emerge victorious anyway.

We get no confirmation the other kids are okay

One important touch near the ending of the book — that the film excises — is a brief glimpse of the four "disqualified" Golden Ticket holders as they leave the factory. In classic Dahl fashion, when Charlie, Wonka, and Grandpa Joe glimpse the unfortunate quartet of children from the great glass elevator, we learn that they have indeed survived their various fates, and will receive a lifetime supply of candy as promised, but they're each grotesquely disfigured by their experience. Augustus Gloop has been squeezed thin in the tubes, Violet Beauregarde has been "de-juiced" but remains purple in the face, Veruca Salt is covered in trash, and Mike Teavee has been stretched 10 feet tall (but thin as wire) by a chewing gum stretching machine. Wonka takes a moment to laugh one more time at each one of them.

In the movie, we are simply left to wonder, and allowed to take away the very real possibility that all four could just be dead. Did Augustus drown in chocolate? Did Violet pop? Is Veruca incinerated? Did Mike Teavee get smushed in his mother's purse? Who knows, they all failed the test. The movie opts for the coldly casual mystery instead of Dahl's final bit of whimsical distortion.