How Historically Accurate Is Munich?

Steven Spielberg has cast his lens over many chapters in history, for the purpose of transferring them onto the big screen. From the presidency of Abraham Lincoln to the D-Day landing and the Holocaust, these theatrical time capsules have showed — for better or worse — moments in civilization that should never be forgotten. Incredibly, though, his 2005 film "Munich" was one entry that, while receiving a decidedly warm welcome (it stands at 78% on Rotten Tomatoes), turned out to be riddled with historical inaccuracies.

The film follows the true story of the Israeli Government's strategic response following the murder of 11 Israeli athletes during the 1972 Olympics in Munich. Determined to bring the terrorist group to justice for their acts, Avner Kaufman (Eric Bana) leads a small team of men to track down and eliminate the targets linked to the murders. In doing so, though, the death toll slowly starts to weigh on Kaufman, along with other members of the team who question their duty and the actions demanded from it.

As much of a critical success as "Munich" may have been — and even boasting five Oscar nominations, via IMDb – there's a lot of rewriting of history on display. Various individuals with links to the event said that specific details bound to the story were, in fact, completely false. So, just how much fact outweighed the fiction in "Munich," and where did the skewed story elements to Spielberg's gripping thriller originate from? Let's take a deeper dive.

Spielberg went by the book for Munich ... in all the wrong ways

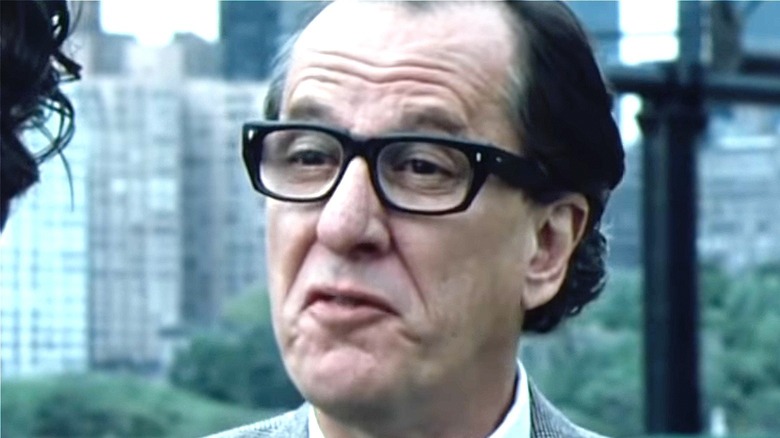

In a Today report in 2005 following the film's release, former field agent Gad Shimron quickly picked apart Spielberg's thriller — that fumbled at the first hurdle, with the team the film focused on. As great as Bana's performance was as Avner, how he was selected and the group that followed him was, it seems, grossly inaccurate.

"Munich" sends Avner off on his mission after being hand-picked by Israel's then Prime Minister Golda Meir, which Shimron assured would not have happened. By introducing 007-like elements to add to the drama (well, Spielberg has always been a Bond fan), Shimron called out the plot point saying, "I know it's tempting to see Golda as a sort of Zionist version of 'M' from the James Bond films, but she had nothing to do with Mossad personnel."

While the recruitment may have been fabricated for dramatic effect, the lead character was already up for debate, as well. Spielberg's most prominent point of reference was George Jonas' 1984 book "Vengeance." The story followed Yuval Aviv (who went by the alias Avner), who gave a personal account of his mission to assassinate those responsible for the Munich killings. However, the book itself was criticized by the Israeli Intelligence Community, who disputed Jonas' source (via HNN). This was later fortified by a report from The Guardian confirming Aviv never operated within Mossad or any other Israeli intelligence for that matter, fortifying inaccuracies with the leader, and his team.

Eric Bana's team should've been bigger and faster than in Spielberg's thriller

While the film "chronicled" the journey of this small group of Mossad agents enacting vengeance against those responsible for the Munich tragedy, it also detailed the mental impact on those involved. A crucial element to the film is the toll taken on members of the group, Avner in particular, as their kill count slowly grows. This is only amplified thanks to the team's lengthy time away and the isolation that spawned from it. The truth, however, is that the research, strategies applied, and time spent prepping the mission took far longer with much greater numbers than the small band of tortured assassins we meet in the film.

An anonymous retired Mossad deputy chief told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, "There was never a single list of targets drawn up, and certainly never a single hit-team assigned to handle them." Instead, agents from being on the lookout for tracking down those responsible for the Munich attacks and report back so that the mission could be a swift one. "It was a matter of putting out the word to our people who were posted in various countries to look out for top Black September members." the anonymous source revealed. "When these were located, then we sent out the right agents to take care of business, on a more ad-hoc basis."

It would've taken more than men to get the job done in Munich

In one of the final hits in Spielberg's historically iffy thriller, Avner and his team take down a contract killer after assassinating one of his own team, Carl, played by Ciarán Hinds. What follows is a cold and remorseless murder by the team as the female threat clings to her last breath before dying on a boat. Of all the prominent female characters in the film, she is the only one who poses a threat to Avner and the hit squad and is far closer to reality than the team after her.

Besides having a network of spies and researchers that aided the actual team that tracked down the terrorist group, Gad Shimron also explained that there was more likely to be women in the field than a team comprised entirely of men. Logistically it makes perfect sense as an effort to avoid attention. "In espionage, like in police work, there is nothing better than having a woman accomplice on hand," Shimron explained. "If you are on a stakeout — say, waiting in a car — and have a lady with you, you are far less likely to be questioned." It's a crucial factor that could've drastically changed Spielberg's film and would've provided more fortified truth to a movie that, in retrospect, was lacking dramatically in it.