Things You Only Notice In Die Hard After Watching It More Than Once

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"Die Hard" is one of the most iconic action movies of all time. It has a great villain, a strong lead, amazing action sequences, and even some emotional heft for a good measure. Due to its enduring popularity — the franchise has grossed more than $1.4 billion as of 2020 — "Die Hard" has firmly earned a spot in the endlessly rewatchable movie hall of fame. Like most rewatchable movies, "Die Hard" has a straightforward story, but is colored in with deeper, brilliant details that make it so much more complex upon closer inspection.

Bruce Willis plays NYPD Detective John McClane. When McClane goes to Los Angeles to visit his estranged wife Holly at her office Christmas Party, a gang of terrorists take over the building. But again, it's not the "what," "why," or "where" that makes the 1988 John McTiernan flick so engaging. It's the "how."

By lavishing care and attention on a movie that could've just been another run of the mill actioner, the folks behind "Die Hard" made something special that is a unique mix of brawns and brain. With that in mind, here's a list of "Die Hard" details you only catch after multiple viewings.

A not so simple plan

While there are many things to love about "Die Hard," one that stands out is the villain and "exceptional thief": Hans Gruber. Hans is smart, smarmy, and played to perfection by the late, great Alan Rickman. It was Rickman's very first movie role (after years of being a stage actor), and the performance is so strong it redefined what audiences expected from a villain in an action film. Prior to "Die Hard," most villains were brawny bullies; in the decades since, the most effective villains have largely been those with enough brains to engage the protagonist in a chess match with the highest of stakes.

But, maybe Hans wasn't as brilliant as we all remember. The more frequently you watch the film, the more his heist plans feels based on happenstance, flimsy logic, and details that left him wide open for a "fly in the ointment" to take the whole operation down.

In order to open the Nakatomi vault and get his hands on $640 million in negotiable bearer bonds, he must open the seventh lock (which utilizes an electromagnetic seal) — and to pull off this Christmas miracle, he has planned all along to have the FBI cut the power to an entire city grid. If the power stays on — if the FBI simply makes one different decision that Hans has not anticipated — the entire mission is a failure and the terrorists either die or go home empty-handed. Hans is a confident guy, but that feels like a heckuva lot to leave to chance.

Both McClane (Bruce Willis) and Al Powell (Reginald VelJohnson) seem to realize that cutting the power will give Hans exactly what he wants; in theory, if either of those men were leading the FBI response, it would be game over right there for Hans. Of course, fortunately for the ex-member of the Volksfrei movement, Hans is instead engaged in a cat-and-mouse game with the agency's resident trigger happy dopes, Agents Johnson and Johnson, who play right into his hands.

This isn't the only convoluted part of Hans' plan. He's also "playing" terrorist to essentially stall for time, planning to blow the roof off the building and — in the aftermath of the carnage — smuggle a team so large they warranted a semi-truck for transportation out of Century City ... in an ambulance? Hans' plan gives the movie its narrative twists, sure — but with so many convoluted steps, it's no wonder it only took one cowboy to bring it down.

Trading a white hat for a white undershirt

"Die Hard" is one of the rare films that fulfills multiple requirements of iconography. It contains iconic performances from Rickman and Willis, an iconic premise that kicked off its own subgenre of films ("Under Siege" is Die Hard on a Boat, "Sudden Death" is Die Hard in a Hockey Stadium), and multiple iconic lines. Perhaps none is more iconic, however, than McClane's delivery of "yippee ki-yay" with a bad word thrown onto the end to punctuate the point.

But, the radio conversation between Han and McClane about "John Wayne, Marshall Dillon" and the rest — building to that famous line — is far from the film's only shout-out to the Western genre. In fact, "Die Hard" is nearly filled with as many Western references as a Clint Eastwood retrospective.

Following the back-and-forth over America's obsession with cowboys and the lone man with a gun narrative, McClane takes on the alias "Roy" after '30's/'40's/'50s cinematic singing cowboy Roy Rogers. Later, when McClane confronts Hans in their climactic showdown, Hans tells McClane, "This time John Wayne does not walk off into the sunset with Grace Kelly."

As McClane is quick to point out, Hans incorrectly referenced 1952 Best Picture nominee "High Noon," a Fred Zinneman classic that actually starred Gary Cooper. Looking back on "Die Hard" after multiple viewings, the moment where McClane barks: "That was Gary Cooper, a–hole," could be interpreted as an early indication that when it comes to this impending showdown, Hans Gruber is already out of his element.

The movie then ends with a quick draw and — surprise — the guy who not only has the training of a police officer but has clearly watched many more Western movies wins. McClane prove he has the fastest trigger finger in Nakatomi Plaza, and all that remains is the mandatory shot of him riding off into the sunset on his horse ... er, Argyle's busted limo.

The benefits of a classical education

The Western, however, is not the only narrative tradition referenced in the film; there are also plenty of references to the classics.

Some appear to be overt, like when Hans looks at the Nakatomi models in the executive suite and seemingly quotes 1st-century Greek scholar Plutarch (specifically, his "Moralia" essay "On Tranquillity of Mind"), saying: "... And when Alexander saw the breadth of his domain he wept, for there were no more worlds to conquer." There's only one problem here: Hans butchers the quote, which in the generally-accepted 1579 translation indicates not that Alexander wept because there was nothing left to conquer, but because "there are an infinite number of worlds, [and] I am not yet the lord of one." When Hans Gruber attributes his smug quotation to "the benefits of a classical education," while inadvertently making the point that taking Nakatomi Plaza doesn't make you the king of anything, it's a wonder Nakatomi CEO Joseph Takagi (James Shigeta) didn't feel the need to stifle a snort.

Other references are built into the machinations of the plot. Hans needs to crack seven seals to break into the Nakatomi vault, for instance, seemingly a nod to the Seven Seals of God from the Book of Revelations. This may appear to be a stretch, but the locks are specifically referred to as seals in the movie and when the vault is finally opened, Hans is bathed in a golden heavenly light.

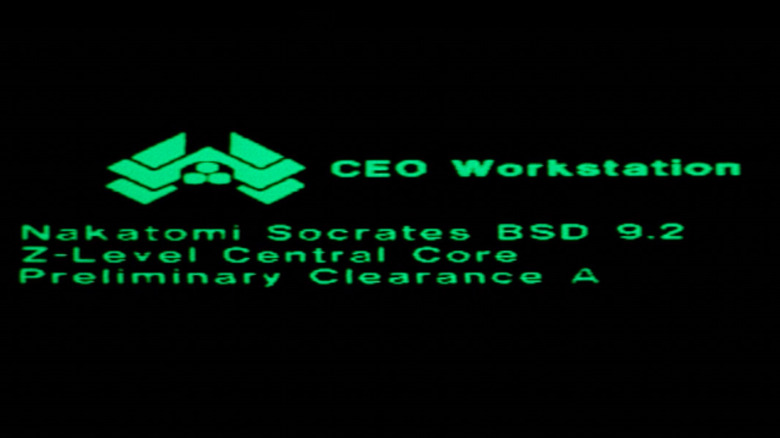

The operating system on Takagi's computer screen at 28:55 seconds into the movie clearly reads "Nakatomi Socrates BSD 9.2," referencing the Greek philosopher. When Hans and company finally raid the Nakatomi vault, the camera lingers on the 19th-century French Impressionist Edgar Degas' painting "Ecole de danse" (supposed estimated value: $4-8 million) at the 1:44:10 mark.

While it is sometimes hard to say with certainty that "Die Hard" is directly alluding to some of these references, it could be argued that if they do exist they are emboldening the film's emotional core: An estranged hero's trial to return to his wife. This narrative touchstone may date back to the last act of "The Odyssey," but it nonetheless holds up after multiple re-watches of "Die Hard" as well.

A rival's education

Takagi doesn't make it terribly long before Hans offs him in the first act. However, in the limited screen time he does have, the Nakatomi CEO makes a lasting impression. Could it be because he's the only one at Nakatomi (besides Holly) who shows McClane any real kindness in the opening? Or is it because he bravely stands up to Hans in an effort to protect his employees? Either way, his brief scenes hold enough weight to merit a few re-watches where attentive viewers may notice Takagi has some pretty impressive credentials.

As an intimidation tactic (and as a power play to show he has studied his prey), Hans goes over the CEO's background while eyeballing the captive crowd. He mentions that Takagi attended University of California Berkeley in 1955, received a law degree from Stanford University in 1962, and finally an MBA from Harvard University in 1970. While Takagi's education is beyond impressive — UC Berkeley was recently listed in the first spot in Forbes' 2021 Top Colleges List, while Harvard and Stanford are Ivy League (and Ivy League-caliber) schools — it's interesting to note he did attend rival schools. UC Berkeley and Stanford have been in bitter competition since their openings and have one of the longest running rivalries in college football. It's too bad Takagi didn't get enough screen time to reveal who he rooted for in the annual "Big Game."

The Lloyd Wright of it all

It's hard to know when a movie will really resonate with audiences the way "Die Hard" did. However, it becomes a bit easier to immerse yourself in the world of a film when it receives so much thoughtful detailing.

One of the best examples of the way this film sets itself apart from other action thrillers is its unique Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired set. According to a "Daily Variety" feature on the set from 1988 (via American Film Institute Catalog), the upper floors of Nakatomi Plaza were a three story set constructed on Stage 15 of the Twentieth Century Studio Lot with a "Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired waterfall."

The waterfall and the combination of rock slabs and long pieces of wood featured on the set are all characteristic of the iconic architect's work. Particularly the waterfall, which feels like a spiritual cousin to one of Lloyd's most recognizable pieces, Fallingwater.

The set design isn't the only thing connecting Lloyd to the film; one of his actual pieces is in the movie. During the walk to Takagi's computer, Hans stops and admires a model bridge displayed in Takagi's office. This model is of Wright's "Butterfly Bridge." Wright proposed the design in 1953 to serve as a bridge between the city of San Francisco and the East Bay cities, but it was never built. While it may take a few viewings to catch little things like these, the production team's attention to detail is beyond admirable.

Where credit is due

While McTiernan should be recognized for his master class in how to film an action movie, the director isn't the only one responsible for a movie's unique look and feel. Luckily for McTiernan, his squad of creative collaborators was even better armed for the challenge than Hans' own crew. His movie operation included production designer Jackson DeGovia, screenwriter Steven E de Souza, and cinematographer Jan De Bont.

Each man contributed mightily to the "Die Hard" phenomenon, as the dialogue, set design, and look of the movie are each cornerstones of its endless watch-ability. In a nice nod to all three men, their names are included on the Nakatomi office directory in the scene when McClane speaks with Hans, who pretends to be "Bill Clay." Just under the name "CLAY," you can see DEGOVIA, DESOUZA and DEBONT.

The directory can be spotted over the shoulder of "Bill," even getting a brief close up. The name come and go quickly on screen, but it's a cool shout out to the sort of key contributors whose roles often go overlooked.

Ode to Gruber

Movie scores and soundtracks can often define an entire production. Simply put, a movie's music has the potential to remain with an audience as long as its characters, action, or dialogue. While this may not always be the case with "Die Hard" after a single watch, multiple viewings reveal some fascinating needle drops that both illuminate and inform several key scenes.

The "Die Hard" score is divided between John McClane and Hans Gruber. When John is making his way through the building, sneaking around, and fighting terrorists, the movie's soundtrack is generally the original score composed by Michael Kamen, which incorporates everything from plucked strings to jingle bells to create a sense of ominous, festive, twisted thrills.

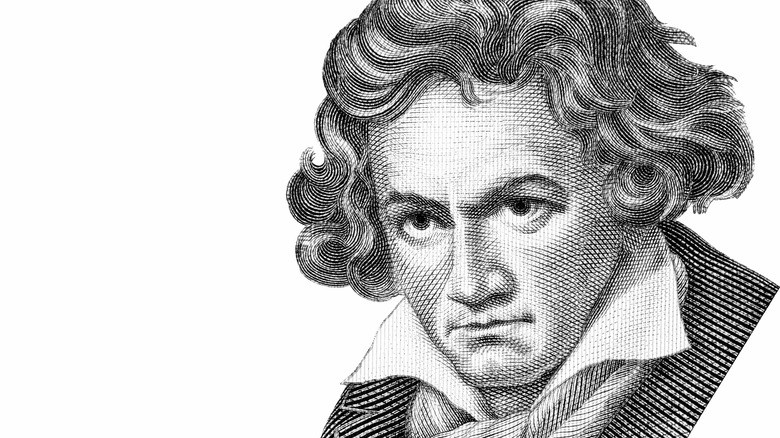

From the first moment Hans and the robbers arrive on screen, however, their presence is marked by the familiar sounds of Beethoven's "Ninth Symphony," which ends in the "Ode to Joy." Kamen weaves pieces of the "Ninth Symphony" in and out of his action score, and Hans even hums the tune a few times over the course of the film. This all culminates with the transcendent vault opening scene, when a bombastic "Ode to Joy" comes roaring over the soundtrack just as Hans lays eyes upon his prize, wind blowing through his hair — a moment foreshadowed more than an hour earlier when we first see the truck entering Nakatomi Plaza to Beethoven's subtle, cello/bass-derived, harmony-removed intro to "Joy."

For the audience, this creates the sensation that Hans has won. His plan is a success, and everything apparently is gravy for Hans going forward. This supposed victory, upon the first viewing, gives the final showdown between him and McClane a unique feeling. There are plenty of famous final showdowns, but how many are prefaced with the bad guy getting the loot while Beethoven roars triumphantly in the background? Upon multiple viewings, however, the music offers so much more.

Painful sounds

Sound design — under appreciated art though it may be — can make or break a movie. For example, imagine if Darth Vader made any sound other than he does while breathing in "Star Wars." It would give the screen legend an entirely different image. While "Die Hard" doesn't may not have any sound design queues as immediately recognizable as Vader's inhaler, a few rewatches reveal how the movie's sound helps builds its tension.

McTiernan leverages sound to place the audience in John McClane's position. The gun shots are loud, the floors make different sounds depending on their surface, and the distinctive elevator ding alerts McClane to the presence of incoming baddies, hatchet men, and stooges.

The movie's sound design also punches up its brutal fight scenes. For example, when McClane and henchman Karl duke it out in the third act, the sound design specifically makes body contact with different materials sound unique. So when McClane tosses Karl into a pile of barrels or the pair land on a stack of steel beams, the individual noises the objects make create a visceral sensation for the audience. Plenty of action movies may bill themselves as "hard hitting," but "Die Hard" is among a special few that implemented specific effects so the audience could get a sense of just how hard those hits are.

Keeping your place

Clever sound design isn't the only way the creative team behind "Die Hard" sucked fans into the action flick. The movie also has clear sign posts on each set to map out where the action is taking place. Nakatomi Plaza is an enormous building — however, the movie's action is mostly isolated to a few floors: the parking garage, the lobby, the 30th floor, the 31st floor, the 33rd floor, the elevator shaft, air duct, maintenance access locations, and the roof.

While McClane takes advantage of the structure of the Nakatomi building to avoid the terrorists, the audience never feels lost, due to subtle place markers in each location. For example, the audience knows John is approaching the air duct whenever he passes the same lewd calendar (he even kisses it when passing the second time, acknowledging it as a breadcrumb), or the audience recognizes the 30th floor as the location of the waterfall and hostages. As the movie progresses, these place markers become key signals for where the action is taking place — and where the next threat to John might come from. These markers even note McClane's location as the building begins collapsing around him.

Much like the sound design, this attention to tiny details does some subtle-but-vital heavy lifting to make the film more engrossing — yet, never disorienting — for the audience. It encourages the viewer to think like McClane, taking stock of which bad guy is where and how "we" might be able to get the drop on them later. Few things make a movie as involving as being able to play-call the protagonist's next move.

Given away by the light

In the back half of the movie, Hans famously pretends to be a Nakatomi employee named Bill Clay when he unexpectedly runs into McClane (the result of McTiernan and crew desperately wanting to engineer a reason for the hero and villain to come face-to-face before the end of the film). The ruse appears to work for a while, because McClane and Hans have only spoken over a radio at this point in the movie. So, when John hands who he thinks is Bill a gun for protection, the audience is on the edge of their seat. If you're watching "Die Hard' for the first time, it looks like the hero has just made his first — and last — mistake.

Of course, the rest is movie history. Hans puts the gun on John, pulls the trigger, and surprise, the gun's empty. But how did John know to give Hans an empty gun?

Some might argue John is — rightfully — paranoid. After all, when he first encounters "Bill," he does ask "What the f–k you doing up here?" in a tone that seems to indicate some suspicion.

However, there's a blink-and-you'll-miss-it detail that may have increased John's suspicions even further. Earlier in the movie, as McClane relays information to the LAPD, he notes that the bad guys are mostly European "judging by their clothing labels and cigarettes." Later, when McClane offers a cigarette to "Bill" (notice how he hands him the entire pack so it is clearly visible to him) the villain in disguise doesn't blink an eye at what would be a harsher, unfamiliar cigarette brand for any red-blooded American.

It's a brief moment, but perhaps one where Hans gives himself away. In a film that frequently plays like a chess match, McClane stays one step ahead.

Silent recognition

The "B" plot of "Die Hard" depicts the redemption of Powell (still grieving an on-the-job accident that resulted in the death of a child), achieved through his friendship with McClane. One of the strongest parts of the movie, Willis and VelJohnson have chemistry most actors would kill for, achieved somehow through scenes where they speak to each other on a radio. When the audience finally sees these two battered, bruised survivors come face to face, it's arguably as powerful a meeting as when McClane reunites with Holly.

However, after multiple viewings of "Die Hard," one question about the pair's relationship might bother some viewers. At the end of the movie, when John walks out of the Nakatomi building, how do he and Al instantly, silently recognize one another? We see McClane scanning the crowd, making eye contact with Al and mouthing something, and the officer nods in recognition as they walk towards each other.

Is it simply an unspoken bond that has developed? At the very least, the scene plays like an acknowledgement of both how sharp these men are, and how close they've become. While figuring out who John is may be easy enough using context clues (Al has likely seen a photo of the McClane's at that point, as Thornburg has been shining the bright light of the media on the family; also, he's the guy hugging his wife, who looks like he just took on a dozen terrorists), there's a sea of LAPD officers running around outside (what's left of) the Nakatomi building by the movie's end.

But that's the good thing about any excuse to look deeper into this and all the other minutiae described above — it gives you an excuse to watch "Die Hard" yet again.