The Ending Of The Humans Explained

The particular brand of indie horror repped by American distribution company A24 has developed a very unique reputation over the years. For the genre's fans, the "A24 horror" tag — as typified by movies like "Under the Skin," "The Witch," "It Comes at Night," "Midsommar," "Saint Maud," etc. — is synonymous with slow, arty, near-impenetrable fare, sometimes more unsettling and bizarre than out-and-out scary.

Even by those standards, though, "The Humans" can be a tough pill to swallow. Described as a horror movie by various film critics during its festival run — Matt Zoller Seitz of RogerEbert.com wrote that it occasionally "feels like 'Hereditary' without the supernatural elements and gore" — the latest star-studded effort from A24 will surely test the patience of anyone who goes into it hoping for an adrenaline rush. For nearly the entirety of its runtime, "The Humans" is really more of a straightforward family drama, following the interactions of a loving yet conflicted middle-class family over one Thanksgiving day; what little "horror" there is in it is limited to the jittery, jump-scare-prone sound design and the quietly ominous style of director Stephen Karam, who wrings the holiday gathering's typical tension and discomfort for all they're worth.

It's not until its final minutes that "The Humans" crosses a line from "vaguely creepy" to outright stomach-churning. It's a climax so intense that it's hard to even process, let alone make sense of. As it happens, that nightmarish closing scene is pretty simple in and of itself; what complicates it, and makes it really terrifying, is the meaning behind it.

The Humans is defined by the looming specter of mortality

To understand the swerve made by the ending of "The Humans," we must first understand what the movie had been doing up to that point. Based on writer-director Stephen Karam's own Tony Award-winning play, "The Humans" is a fraught text that uses its Thanksgiving framing to explore some of the headiest issues surrounding the life of the average American: faith, matrimony, post-9/11 paranoia, post-2008 economic insecurity, the meaning of success and happiness, etc. But there's one theme that hovers above it all as the piece's defining source of anxiety: death.

In adapting his deceptively-simple play to the screen, Karam apparently opted to emphasize the subtext of the specter of mortality with cinematic tools. The critics have a point: "The Humans" is, indeed, shot like a horror movie, with whole sequences that ratchet up the tension via careful camera movements and lighting. The reason it doesn't entirely register like a horror movie is that there is no tangible, immediate threat for the characters to face. Instead of a killer or a poltergeist, the evil haunting Brigid's (Beanie Feldstein) rundown apartment is the very tragedy of the human condition.

This is apparent everywhere, from the characters' own repeated discussions on the topic to the ailing health of Aimee (Amy Schumer) and Deirdre (Jayne Houdyshell) to the oft-referenced near-death experience Aimee and Erik (Richard Jenkins) had on 9/11. In fact, the theme of death is the whole reason the movie is set during Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving brings the anguish to the forefront

Why do some scenes in "The Humans," even before its bleak finish, feel so creepy and despondent? The answer: because of the tragic ironies undercutting them. Thanksgiving is America's official day of mandatory cheer, camaraderie, and gratefulness, the day everyone gets together to celebrate the bounty of life. But the unspoken truth of Thanksgiving is that it's a day tinged with despair, a forceful celebration of the necessarily ephemeral. It's a day in which people spend time with the loved ones they know they'll lose one day, gorge on delicious food while earthly pleasure is available, and give thanks because they know, deep down, that nothing is guaranteed — not even the next Thanksgiving.

Moreover, it's a day on which people force themselves to have a good time even as life, in all its shiftiness and mystery, nearly pulls them apart, both at the seams, and from each other. If family is "all we've got in the end," as Erik repeatedly insists, then Thanksgiving, with all its squabbling and frustration, brings the additional irony of exposing just how fickle, how ultimately precarious, even the institution of family is. On no other day do we dangle closer to the abyss of existence's inherent loneliness.

That is the bogeyman of "The Humans." And, once the screenplay has alerted us to it, Karam's haunted-house directorial tactics make us feel it. It's like a physical menace; the darkness, the noises, and the negative space are reminders of the existential dread the characters are doing all they can to ward off.

The horror builds slowly

For most of the movie, Karam just lets that horror — of being helpless against the passage of time, of not knowing what's coming, of being aware that we all die alone — linger. The script takes many avenues to explore the characters' thinly-veiled agony: Erik laments what little a lifetime of work has come out to, Aimee admits that marriage is just "choosing to be unhappy with someone else," and Richard (Steven Yeun) contemplates waiting for his trust fund and starting life at 40 years old. Meanwhile, two ghosts — one real, one imagined — haunt the apartment. The Alzheimer-riddled matriarch Momo (June Squibb) represents a kind of death in life, constantly reminding the characters of the impermanence of sentience whenever they look at her. There's also Erik's story about the faceless woman of his nightmares — herself an avatar for his 9/11 trauma — who clues us into what he may be seeing and dreading in all those big dark voids.

Then, as the evening draws to a close, the characters are naturally pushed to confront the finality of life at large. Specifically, that Thanksgiving will end, as all things must. It's at this point that Karam accelerates the proceedings by staging a series of heavy moments in which the subtext nearly becomes text: Momo briefly goes missing; dessert is served but never eaten; Deirdre feels spooked out on her way to the bathroom; a confrontation breaks out between mother and daughter. You can almost sense the horror movie finale coming. And yet it's still a shock when it does.

The ending's events are pretty clear-cut

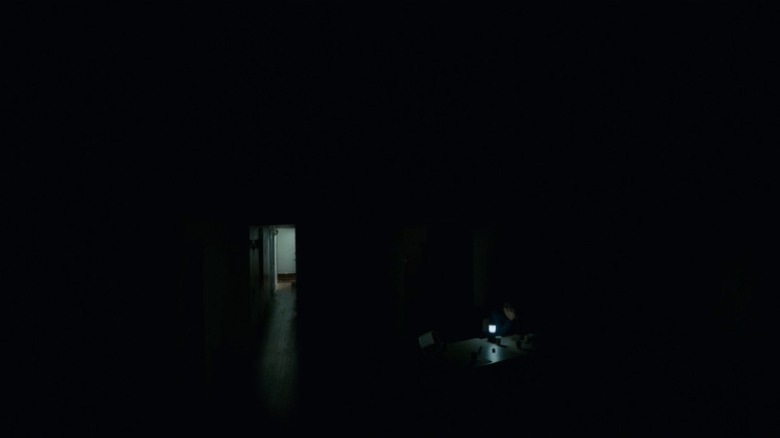

What happens at the end of "The Humans" is quite straightforward. Left behind in the apartment as Deirdre and Momo make their way to their ride, Erik suffers a panic attack when the power goes out and darkness engulfs him. The noises that have been droning on all night appear to become louder, he feels alone and helpless, irrational fear sets in, and he's reduced to wailing and praying to the Virgin Mary until Brigid comes calling and snaps him out of it.

The film's realism is not breached at any point by that final sequence. After all, the loud noises are just a reflection of Erik's panic, and the old lady who walks past the front door is just an inoffensive neighbor. But it hits like the scariest, most nightmarish movie scene of the year.

There are many reasons for that. The first, simply put, is that it's a highly effective slice of horror direction. Karam deploys the empty space and the pale lantern light masterfully, getting us to fill in the dark with our own fears. The second is the specter of the faceless woman. If she's the one Erik could bring himself to open up about earlier, we can only imagine what other nightmare figures have been percolating in his head. The moment the lights go out, it's like he's been physically placed in a room with all the unspeakable things he's spent the whole movie refusing to describe.

But the main source of the scene's horror is even deeper — cinematically, and existentially.

Erik is left to face the void alone

The defining irony of "The Humans" is that, for all their effort to be together, the characters constantly find themselves completely alone around Brigid's empty, oversized two-story apartment. Each moment of sudden isolation is like a nudge on their — and our — shoulders: Even while sharing the same home, we're reminded, humans are constantly drifting away from each other.

That cold, crushing loneliness the characters keep returning to is the whole precipitating factor of Thanksgiving — and, by extension, of all our quests for love, companionship, respite from ourselves, respite from the void. In a sense, "The Humans" tells the story of a bitter struggle, a persistent and coordinated effort by the Blakes to keep the void at bay.

This, more than anything, is why the final scene is so gut-wrenching. Erik's family was just with him seconds ago, and suddenly there he is, all alone, with none of his loved ones to help him face his demons. The paradox between physical proximity and existential seclusion apparent throughout "The Humans" finally comes to a head as the camera pulls far back, revealing that Erik is positively suffocated by nothingness, in a place where just moments ago there was warmth and love. Even his trembling, last-resort prayers could be said to illustrate the necessary — yet limited — solace of religion for us humans. After all, we are like Erik, fumbling our way through the dark, holding on for dear life as the noises we've walled off get louder. If only our troubles were so simple as horror movie monsters.