The Untold Truth Of Finding Nemo

It's rare to find a movie both parents and kids can love equally, especially when said kids are likely to force said parents to watch it somewhere in the range of 10,000 times. But that tricky balance is where Pixar excels, and "Finding Nemo" hits it beautifully. For almost 20 years, kids have loved its cute animal characters and zany comedy, especially the antics of Ellen DeGeneres as the amnesiac regal blue tang Dory. But like its richly realized underwater world, "Nemo" has a lot more going on underneath the surface. With its neurotic protagonist Marlin (Albert Brooks), it offers one of the movies' most powerful stories of parenthood and all the terrors that come along with it. Before "Up" solidified Pixar's reputation as a sob factory, "Nemo" makes the tragedy of a father separated from his son heartbreakingly real even if it plays out with cartoon clownfish.

Pixar spent years hammering out "Finding Nemo" to get all these elements just right, and it can open up a whole new level of appreciation for this masterpiece to see just how much creativity went into it. Here are just a few of the strangest stories from behind the scenes and under the sea.

Finding Nemo is based on a true story

What sets Pixar apart from every other animation studio is just how personal their stories feel. At least in the case of "Finding Nemo" writer-director Andrew Stanton, that's because it is. In his introduction to "The Art of 'Finding Nemo,'" Stanton recalls how the movie began taking shape all the way back in his childhood: "I remember going to my family dentist, who had this funky fish tank in his office ... I assumed, when I was a child, that all fish in tanks were originally from the ocean and wanted to go home."

That story stayed in the back of Stanton's mind for decades as he grew up and began working for Pixar. A trip to Marine World with his son Ben convinced him fish were the perfect subject for the new computer animation medium, but he still needed a story that "mattered to me emotionally." Once again, an outing with Ben provided the answer. One day, Stanton took his then-five-year-old son for a walk to the park, and he caught himself spending the whole time panicking about all the ways Ben might get hurt. He realized his fear for his kid's safety was stifling both of them, and that realization soon grew into the driving conflict of the film for Marlin and Nemo.

Pixar had a macabre method of digitizing fish

The Pixar crew are some of the biggest perfectionists in the business. In his audio commentary, Stanton describes spending six months on a scene that comes and goes in a second with only a little regret. The "Making Nemo" documentary describes the crew going through weeks of field research and technological development to make the underwater "set" look real — and then doing too well and having to dial it back so it could work in a cartoon.

That documentary also reveals the unexpectedly macabre way Pixar brought their cast of lovable talking fish to life. Art director Robin Cooper doesn't sugarcoat it: "Tropical fish die a lot, unfortunately. So they always have a good supply, at fish stores, of dead fish." This gave the animators plenty of specimens to study, and in her words, "slap it on the scanner" for future reference.

Sharks are more than a little too big to fit on a scanner, though, so the process for researching Bruce and the gang was even spookier. "The Art of" describes how Dr. Adam P. Summers, an ichthyologist at the University of California at Irvine, gave the crew access to an "Indiana Jones-like warehouse ... full of prehistoric fish and specimens from the 1800s." Those elderly shark carcasses were invaluable for Pixar's design team, giving them their best shot at an up-close look at the apex predators with all their body parts intact.

Pixar repurposed its hair and cloth software to make the anemone

In many ways, computer animation seems a lot easier than the painstakingly hand-drawn and hand-painted animated movies of past generations. Instead of deliberately placing every line and brushstroke, the Pixar crew can run complex simulations that allow the computer to do most of the work for them. On paper, that seems to take much less creativity. But sometimes figuring out how to get the computer to do the work takes quite a bit.

For instance, the 10th anniversary roundtable reveals how they were able to animate the hundreds of waving tendrils of Nemo and Marlin's sea anemone home. Technical lead Oren Jacob explains: "Somebody said, hey, on 'Monsters' they're doing fur, so why don't we take a tennis ball, stick a bunch of foot-long fur on it, and turn gravity upside-down? We're like, oh! And we had an anemone the next day." The final version combined that with other textures — software developer Andy Witkin describes them as "cloth sacks" — to allow Pixar to use its old tools to create a creature its designers had never touched before.

That's not the only time they used a similar approach. Jacob challenged the other filmmakers to guess how he rendered the ocean floor. The answer: He took the wave simulator and froze it.

The sharks began life as an explosive volleyball team

Marlin and Dory have barely left home when they run into a nasty-looking great white shark named Bruce who takes them to a ruined submarine surrounded by floating mines. Fortunately, he turns out to be a nice enough guy. As he reminds his AA-style group for sharks, "Fish are friends, not food" — at least until he gets the scent of blood and chases after Marlin and Dory after all.

Dory confuses the round mines for balloons, but the writers originally had a different visual pun in mind. As he explains in the commentary, Stanton's original idea was that the sharks were such natural thrill-seekers that their idea of relaxing was using the mines as volleyballs, and Dory would get her answer the hard way when she asked why it was so important not to drop them.

But the writers' room was concerned that the scene needed more action, and that submarine was just sitting in the background doing nothing when it could instead be the perfect location for a chase scene. Fortunately, the animatic — storyboards combined with a temporary voice track — is still available on Disney+ for viewing. Even more fortunately, the mines stayed in the movie, leading to one of its most hilarious moments when a stray torpedo hits one with an understated "ping!" that quickly escalates into a cacophonous explosion when it sets off a chain reaction blowing them all up at once.

Bruce the shark was named after a classic prop from Jaws

Pixar is unique in the animation field for being equally beloved by general audiences (kids and adults) and movie buffs. Maybe that's because the Pixar crew are such big buffs themselves. Fans may recognize nods to past animation classics like "Bambi" and "Pinocchio," along with more left-field choices like "Psycho," "The Birds," and "The Shining." Most of these are pretty small and straightforward, but there's also a major character whose significance you might miss without some knowledge of backstage lore.

The blockbuster success of "Jaws" changed the movie industry forever, but for a long time, it looked like it would barely reach the screen at all. Unlike Pixar, director Steven Spielberg couldn't create his ocean-based thriller from the safety of his computer. He schlepped his whole crew out to film on the real thing, which proved so difficult they frequently only filmed a few hours a day. But the ocean didn't cause half as many troubles for the human crew as it did for the life-sized mechanical shark, whose delicate inner workings didn't mix well with saltwater. That turned out to be a blessing in disguise, forcing Spielberg to get creative by suggesting the shark without showing it and making a masterpiece of suspense. The director nicknamed his uncooperative star after his lawyer, Bruce, and "Jaws" in turn passed the name on to the ringleader of the "Finding Nemo" shark gang.

Gill lost a subplot

While Nemo's father is searching for him, Nemo plays out a parallel plotline in the fish tank of a dentist's office where he meets an alternative father figure. Played by the always-reliable "Spider-Man" and "Last Temptation of Christ" star Willem Dafoe, Gill made a big impact on a generation of kids despite his relatively brief appearance, introducing them to the archetype of the stoic badass with a troubled past.

But for a good chunk of the development of "Finding Nemo," Gill was none of those things. In the same way that Marlin grows past Nemo's vision of him as a loser into a larger-than-life hero, Gill's bravado was originally conceived of as nothing but an act. Like Nemo, he wants to escape because he originally came from the ocean, but a deleted scene would have revealed that his history was one big lie, as Nemo discovers when he learns Gill stole it all from a picture book in the waiting room. On the commentary, co-director Lee Unkrich explains why that subplot had to go — it made Gill too unlikable, and it ate up valuable screen time, tipping the balance between the parallel storylines too far away from Marlin. "For taking that out," Stanton says, "We ended up cutting the amount of tank sequences in half."

Not every fish survived the animation process

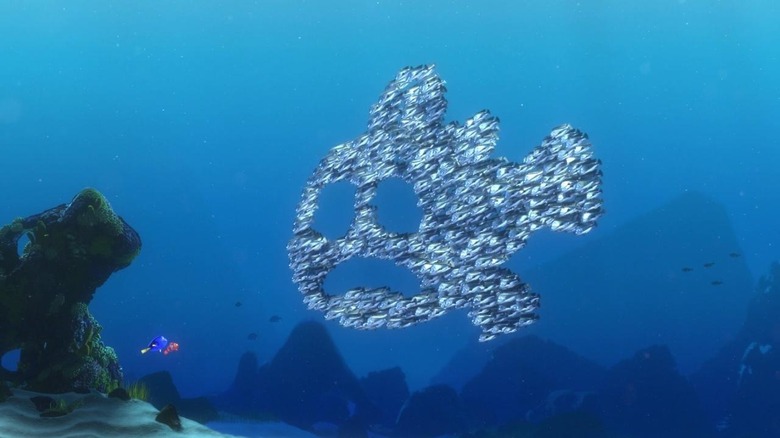

Computer animation is a difficult mix of technology and artistry, and several scenes in "Finding Nemo" proved equally challenging from both sides. One of the most difficult sequences introduced a school of moonfish that move as a unit to form shapes like a lobster, a ship with working cannons, and a nasty caricature of Marlin. This and similar scenes were so complicated that the crew included a dedicated "crowds lead" named Justin Ritter. In the original DVD's unique "visual commentary" — which interrupted Unkrich, Stanton, and writer Bob Peterson's comments with mini-documentaries and other visual aids — Ritter explains how the production simulated fish schools' movements. But each of the moonfish's shapes required different numbers of fish, a process Ritter gives a hilariously dark description: "We would put a lot of fish in and then just kill the ones that were misbehaving. So, basically, hundreds of CG fish died to make this movie."

Finding Nemo led some big stars to some undignified places

"Finding Nemo" brought together an all-star cast led by Albert Brooks, best known for roles in films like "Drive" and "Taxi Driver," as well as directing himself in classics like "Defending Your Life" and "Modern Romance," along with sitcom star and talk show host Ellen DeGeneres. That star power goes all the way down the line to the bit parts, like Brad Garrett from "Everybody Loves Raymond" as one of Nemo's tankmates and future "Hulk" and "Munich" star Eric Bana as a shark. This could sometimes be a surreal experience: Stanton remembers directing Allison Janney of "The West Wing" as Peach the starfish: "You're standing there having Allison Janney, this Emmy award-winning actress, reading these lines and going oh my gosh, okay, I hope you're not offended that I'm having you read about the AquaScum 2003!"

It was even weirder working with Geoffrey Rush, who had won an Oscar for his role as a pianist recovering from a mental breakdown in "Shine" and would be nominated for three more, including "Shakespeare in Love" and "The King's Speech" — though you may know him best for the scene-stealing villain he played in the "Pirates of the Caribbean" movies. For "Finding Nemo," Stanton says, "He had to do dialogue as a pelican with water in his gullet, and it just wasn't sounding right, so we had him hold his tongue ... and I remember just having this flash moment going, I just told this Oscar-award-winning actor to hold his tongue and read this line and he's doing it, wow."

That's the director playing Crush and the seagulls

Not every role was right for a celebrity voice. Before most of them were cast, the crew recorded a temp track with their own voices, and a lot of those temporary voices worked so well they were never able to find anyone else who could do them better. That's how some behind-the-scenes talent found themselves on the cast list, including writer Bob Peterson as Nemo's enthusiastic, singing teacher Mr. Ray and co-writer Joe Ranft as Jacques the cleaner shrimp.

As it turns out, some of the most memorable voices in "Nemo" came from its director. Stanton appears as both Crush the surfer-dude sea turtle and the chorus of seagulls, who, even in a world of talking animals, still can't express any thought more complex than "Mine!" In the commentary, Peterson asks him, "Were you going to let anyone else do voices in this film?"

In fact, Stanton resisted using his own voice for Crush as long as he could, trying to hunt down the perfect actor all the way through the first test screening. That first audience liked his performance so much that it finally stayed in. Based on Unkrich's description of the recording sessions, it's no wonder: "A lot of the Crush dialogue was just one two-hour session in my office. ... [Stanton was] just a vessel for a higher surfer that day. It all started flowing, it was great. I just got out of [his] way."

The crew spent a day in the sewer for a scene that got cut

Pixar went to great lengths to make sure "Finding Nemo" was believable. Producer John Lasseter says in "Making Nemo" that he saw to it that everyone on the crew was scuba-certified so they could animate life under the sea from experience. Not all of their research was that pleasant — and sometimes it all went to waste anyway.

In the roundtable, producer Graham Walters remembers going on a tour of the San Francisco sewage treatment system with Stanton to make sure they captured it accurately for a planned sequence of Nemo escaping into the ocean through the dentist's toilet. As anyone who's been in smelling distance of a sewer, let alone inside one, can tell you, it couldn't have been much fun. Stanton pressed their guide to see if there was any way for a little clownfish to safely get through all the machinery. The answer was a flat "no."

They pressed on with the sequence anyway. But when the time to animate it came around, the writers' room agreed it was slamming the brakes on the movie's emotional climax, when Marlin thought Nemo had died, instead of moving the story forward. In the final film, it's cut down to a few seconds.

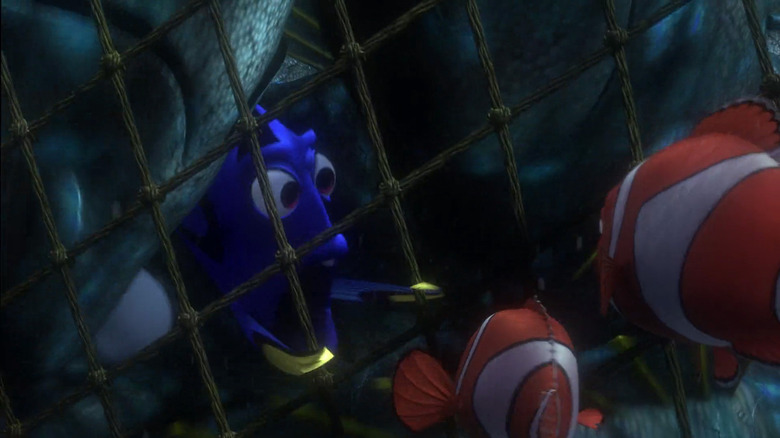

A news story inspired the climax

Marlin and Nemo are finally reunited in the Sydney harbor, but they barely have time to say "hi" before they're in peril again and Dory gets swept up in a fishing net. Nemo gets to use the skills he learned with the tank gang to lead the fish to swim down until they overwhelm the net, and Marlin gets to atone for his overprotectiveness by trusting Nemo to take that risk. Nemo's plan works, but that has to be pure Hollywood fantasy, right?

Well, no, it doesn't. In fact, if it hadn't happened in real life, it never would have happened in the movie. In the commentary, Stanton explains the origin of the sequence. When he was first outlining the plot, the director struggled to think of an ending that would live up to the spectacular adventures along the way when the answer presented itself: "I found this little article in the back of the paper ... about these cod fishermen in Norway who tried to pull up a whole net of fish, and all the cod didn't want to go on the boat, and they all sort of swam down in unison and capsized the boat. And I just thought that was fascinating, just the collective might of all these fish." That's pretty much exactly what made it into the film, with one major change: Disney executive Roy Disney told Stanton, "Do me one favor. Don't capsize the boat. It's bad luck for sailors."

The computers had some trouble with the net scene

The net contains hundreds of fish, and once again, Pixar had to turn to simulations to handle them all. On the commentary, Peterson describes the sequence as "so easy that we're still working on it right now as we speak." This segues into another mini-documentary, where Oren Jacob breaks down how he was able to augment the hand-animated "hero shots" (close-up and medium shots) with computer simulations.

But the computer wasn't working at quite the same level of genius as Pixar's human side. Sometimes fish would get stuck outside the net, and Jacob describes the surreal image of watching them try to get back in while all the others are trying to escape. As with the moonfish, the solution was to "kill" the fish on the wrong side before anyone outside the studio could see how the computer had goofed. Even with the technological help, it still took a "whole team of folks" to correct the program, one fish at a time, in collaboration with the animation side of production managing the fishes' "acting" to get that right note of panicked frenzy.