The Untold Truth Of The Grinch

Of all the many Christmas-themed movies, books, and TV shows that audiences can readily consume and re-enjoy each and every November and December, a handful are non-negotiable. Millions of holiday revelers will make time amidst the hustle and bustle and eschew so many other entertainment options to cozy up with Dr. Seuss's "The Grinch," be it in the form of the 1957 storybook "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!", the 1966 animated TV special, the 2000 live-action film, or the 2018 animated movie.

While each take on the character and the story is executed a little bit differently, the endearing and enduring gist remains the same. The Grinch, living a lonely life with his dog Max on a mountain as chilly as his heart and soul, has his fill of the cheerful yuletide spirit of the Whos of nearby Whoville, and he steals Christmas — all of it, every light, decoration, and even the roast beast. Of course, he learns the real meaning of Christmas by the end, and he comes to love the holiday and all it represents.

He's a mean one, that Mr. Grinch, but he's one of the most famous holiday characters of all time. Here's a look into the long and delightful history of the notorious green guy.

The Christmas-thieving Grinch was not Dr. Seuss's first Grinch

"How the Grinch Stole Christmas!", the original book and its assorted adaptations for television and film, include the most famous and definitive usage of the word "Grinch," the personal and species name of the titular holiday-hating monster — but it's not nearly the first or only time Dr. Seuss employed its use. "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" was first published in 1957, but in a summer 1955 issue of Redbook magazine, according to the Smithsonian, the author published and illustrated a poem called "The Hoobub and the Grinch." In this instance, the Grinch is a huckster who sells a piece of string for the exorbitant price of 98 cents to a furry, yellow, sunbathing boor.

And while that Grinch isn't too far removed from the latter one, character-wise, Dr. Seuss used this made-up word in his 1953 children's book "Scrambled Eggs Super!" Withdrawn from publication due to offensive content concerns (per CNN), it concerns a kid named Peter T. Hooper who makes scrambled eggs from the shelled, edible leavings of various exotic birds. Among the creatures he encounters is the "Beagle-Beaked-Bald-Headed Grinch." Resembling a vulture but covered in a thick layer of Big Bird-yellow fur, its eggs aren't scrambled because on the day Peter encounters him, it isn't laying any.

Dr. Seuss didn't have to look far to find inspiration for The Grinch

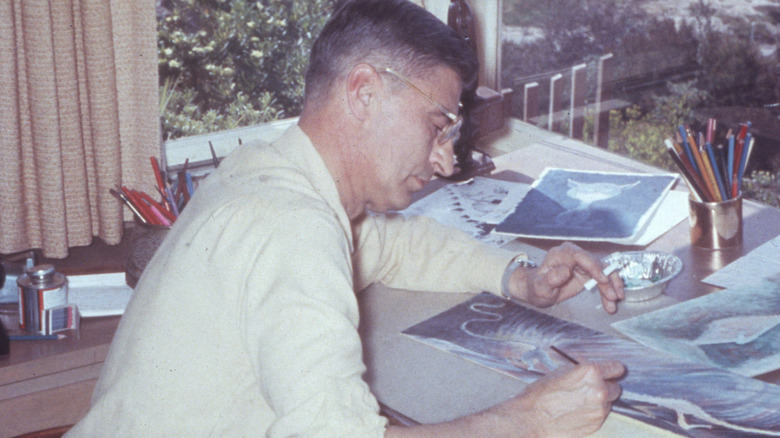

Fortunately, "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" is not directly based on true events. No town called Whoville was ever besieged by a furry green malcontent from the mountains (and his dog) who robbed all of their homes on Christmas Eve. Unfortunately, The Grinch himself is based on a real person — his creator, children's literary icon Theodor Seuss Geisel, who wrote under the pseudonym Dr. Seuss.

Geisel was brushing his teeth on the morning after Christmas in December 1956 when he noticed he didn't feel right. "I noted a very Grinchish countenance in the mirror," he told Redbook (via "Dr. Seuss: American Icon") upon the publication of "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" in 1957. "Something had gone wrong with Christmas, I realized, or more likely with me." That inspired Geisel to write the classic Christmas tale, as did the motivation to "rediscover something about Christmas that obviously I'd lost."

According to Biography, it took Geisel just a few weeks to make the "Grinch" manuscript, the only trouble coming when he needed an ending — he didn't want it to be overtly and explicitly religious, and settled on the scene of the title character and some Whos dining on "roast beast" together.

The book helped make Dr. Seuss into a literary titan

The Grinch has factored into the celebration of the end-of-year-holidays for millions, for a really long time — and in various ways. Two big-screen movies depicting The Grinch's drive to eliminate (and then embrace) Christmas were huge hits. Ron Howard's 2000 live-action "How the Grinch Stole Christmas" starring Jim Carrey was the #1 grosser of 2000 and earned a total of $345 million, outpaced in 2018 by Illumination's animated take (featuring the voice of Benedict Cumberbatch), which took in $514 million. Annual event airings of Chuck Jones' 1966 animated TV special routinely draw in millions of viewers, too, but Dr. Seuss's original rhyming, illustrated children's storybook continues to be a publishing phenomenon.

"How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" was first published in 1957, a breakout period for Dr. Seuss. Twenty years after the publication of his first kids' book, "And To Think That I Saw it On Mulberry Street," Seuss enjoyed blockbuster sales for "The Cat in the Hat." According to the Smithsonian, Random House anticipated such demand for Seuss's next book, "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" that it ordered a hefty first run of 50,000 copies. It's since sold 7.5 million copies as of this writing, per Forbes, placing it among the most popular children's books of all time.

The Grinch was Dr. Seuss's favorite of his creations

Dr. Seuss (real name: Theodor Seuss Geisel) is arguably the most famous, beloved, and influential children's book author of all time. Over a career that spanned more than 50 years, he wrote and illustrated dozens of books for young readers, a good number of them classics of the form, including "Green Eggs and Ham," "Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories," "Oh, The Places You'll Go!," "And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street," and "If I Ran the Zoo." Along the way, he invented hundreds of characters that became better-known than even their source material, like The Cat in the Hat, Horton the Elephant, and The Grinch, a nasty green monster who successfully steals Christmas from a small town. But he loved one more than any other.

"The Grinch was Dr. Seuss' favorite character, it was his all-caps vanity license plate," Seuss biographer Brian Jay Jones told the Smithsonian. Jones also related the story of two kids from New Jersey, Bob and David, with the unfortunately coincidental last name of Grinch. They wrote a letter to Dr. Seuss complaining that they got teased around Christmas every year because they shared a name with a monster. "Seuss wrote them back and basically said, 'No, the Grinch is a hero, a changed man. Tell those other kids, it's not where you start, it's where you end up."

Dr. Seuss didn't want to make a TV special at first

As one of the best-known and most widely-read American authors of all time, it's notable and surprising that Dr. Seuss's works weren't adapted into big-budget, sure-to-hit feature films until the 2000s — about a decade after the writer's death in 1991 — among them "The Cat in the Hat," "Horton Hears a Who!", and "The Lorax."

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, when Seuss was at his creative peak his books were selling millions of copies, the author was reluctant to allow anyone from Hollywood to turn his books into screen-based entertainments. According to Biography, veteran Warner Bros. director Chuck Jones met Dr. Seuss during World War II — Jones made cartoon instructional videos for the Animation Department of the U.S. Army's First Motion Picture Unit, commanded by Dr. Seuss (a.k.a. Theodor Geisel). The personal connection opened the door for the 1966 adaptation of "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!", which hit TV nine years after the book version was first published. Still, Seuss still had reservations during preproduction, namely that he thought Jones too closely modeled the animated version of The Grinch after himself.

How The Grinch got adapted for television

Dr. Seuss's original 1950s text of "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" comprises just over 1,300 words and 64 pages. The 1966 TV special runs 26 minutes, a significantly longer chunk of time than it takes to read the entirety of the book, even at a slow pace. It fell on director-producer Chuck Jones, screenwriters Irv Spector and Bob Ogle — and a big assist from Dr. Seuss himself — to pad, stretch, and massage the skeletal story so that it could fill out a half-hour time slot.

Songs aren't merely a hallmark of both holiday specials and children's television, they can eat up a lot of screen time, too. "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" includes nine musical performances, including "Welcome Christmas" and the three-part "You're a Mean One, Mr. Grinch," both which feature lyrics written by Seuss. "It was poetry to him," biographer Brian Jay Jones told the Smithsonian. "In the archives, I found handwritten notes with all these various scratched-out iterations. You could see how much fun he was having coming up with 'stink, stank, STUNK!'"

One other big move that extended the running time and fleshed out the story: the writers elevated Max the dog, The Grinch's long-suffering sidekick, to major character status, requiring many bits of plot development and reaction shots.

Why The Grinch is green

Only a few cultural phenomenons are impactful enough to permanently alter the public's perception, and create a connection with, something naturally-occurring or pre-existing like a color. Dr. Seuss's Grinch character is just that famous and popular — colloquially, and also in the worlds of professional colorists and paint creation, the Christmas hater's unique body color of sickly, pale yellowish-green is known as "Grinch Green." It's actually one element of the well-realized character that Dr. Seuss didn't personally conceive. The original "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" storybook from 1957 was printed primarily in black and white, with some Christmas-appropriate red spot illustrations added throughout. The Grinch himself is black and white; not green at all.

The Grinch acquired his definitive green when Chuck Jones adapted the Dr. Seuss book into the 1966 holiday TV special of the same name. Television had switched to color by that point, and according to Biography, Jones injected some vibrancy into the material in the form of shades and hues to depict the Grinch and Whoville. He made the Grinch green, and that particular shade of green, inspired by a running joke in his real life. Every time he rented a car in the years preceding production on the special, Jones found, the agency would give him a vehicle in that sickly, pale yellowish-green color.

Audrey Geisel wielded much power over the Grinch movie

After Dr. Seuss died in 1991, his wife, Audrey Geisel, became a fiercely protective guardian of her husband's literary works. The first feature film adaptation of one of those books, "Dr. Seuss's How the Grinch Stole Christmas," directed by Ron Howard and starring Jim Carrey, arrived in 2000, two years after multiple Hollywood power-players entered an intense pitch-fest in a Beverly Hills conference room presided over by Geisel. According to Newsweek, Tom Shadyac, John Hughes, and a team-up of Brian Grazer and Gary Ross all failed to impress Geisel with their theoretical "Grinch" adaptations, with the latter wanting the titular Christmas thief to travel into other Seuss books along the way. Geisel allowed Grazer to return in two days with a pitch more faithful to the source material, and he enlisted Howard, his producing partner and frequent collaborator. Howard developed an outline during a flight to California and that won Geisel over — on the contingency that they could get Carrey to play The Grinch.

Once filming began, Geisel kept creative control and exercised her veto power. She made filmmakers eliminate a somewhat anti-Semitic joke about a non-Christmas-celebrating Whoville family named The Who-Steins, a "Who-venile delinquent" teenage character, and a lot of potty humor. "There were too many bathroom jokes," Geisel said. "That's not the Seuss world, not at all."

The Grinch might be a python

Like so many other fantastical, fictional characters, The Grinch is solely the invention of children's book author Dr. Seuss, and he's a loner whose "otherness" is explicitly depicted by an appearance and physicality that doesn't match anybody or anything else. The Grinch is said to have a heart "two sizes too small," which could be very influential on his physicality and mental state. "You're going to have that small heart beating twice as fast" to pump enough blood around the body, Johns Hopkins University cardiology professor (and Grinch scholar) Dr. David Kass told KPBS. Such a physical issue could lead to grumpiness, Dr. Kass theorized.

But then The Grinch's literal heart, when he lets Christmas into his metaphorical heart, is said to grow "three sizes." This isn't unheard of in nature. "He's really a snake. I mean not just any snake, he's a python," Dr. Kass explained. A Burmese python's heart, specifically, rapidly and significantly grows right after eating. The cardiologist points to two textual clues that suggest The Grinch is this kind of snake — the heart growth occurs around the time of a large meal of "roast beast," and when he meets Cindy Lou Who, the character "slithered" around, all serpent-like.

Music is very important to The Grinch

The various and assorted Grinch projects boast an impressive and high-profile musical pedigree. The 1966 made-for-TV animated special "How the Grinch Stole Christmas!" included songs co-written by Grinch creator Dr. Seuss (and memorably sung by deep-voiced vocal actor Thurl Ravenscroft), and the 2000 live-action feature film "Dr. Seuss's How the Grinch Stole Christmas" included a slew of original songs performed by the likes of superstars of the era such as Smash Mouth, Barenaked Ladies, *NSYNC, and Faith Hill.

When Illumination went into production on 2018's feature-length, big-screen animated "The Grinch," the studio commissioned music from Danny Elfman, Oscar-nominated composer of scores for "Batman," "Beetle Juice," "The Simpsons," and "The Nightmare Before Christmas." For a contemporary take on the old special's famous central song, "You're a Mean One, Mr. Grinch," Illumination teamed up Elfman with genre-bending rapper and songwriter Tyler, the Creator. According to Entertainment Weekly, the duo traded takes on the song until they worked it into something they both liked. Tyler then outdid himself, turning out a whole EP's worth of songs about and inspired by The Grinch and classic Christmas music.

The Grinch returned for two now obscure animated specials

The Grinch is the centerpiece of a bankable franchise, the subject of multiple feature films as well as numerous specials made for broadcast television. While the 1966 TV cartoon "How the Grinch Stole Christmas" is the best-known and easily most popular of small-screen Grinch fare — and 2020's critically-savaged, little-watched televised stage show "Dr. Seuss's The Grinch Musical" starring Matthew Morrison is the most recent — the character appears in two other largely forgotten one-shots.

"Halloween is Grinch Night" first aired in 1977. With a teleplay by Dr. Seuss, the special is a prequel to the Grinch's other, better-known story, and this time the nasty character tries to bring chaos to Whoville on Halloween (not Christmas), only to be thwarted by local boy Euchariah Who (instead of Cindy Lou Who). Five years later, The Grinch came back, his taste for mean-spirited mayhem focused directly on fellow Seussian character The Cat in the Hat. In the crossover special "The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat," The Grinch sets out to torment the mischievous feline. Both specials were reasonably popular and acclaimed upon their initial releases. "Halloween is Grinch Night" and "The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat" won Emmy Awards, for Outstanding Children's Special and Outstanding Animated Program, respectively.

Why The Grinch hates Christmas

Every medium featuring The Grinch, be it book, live-action film, animated film, TV special, or stage musical, is character-driven — they all depict the methodical, calculated, and cold process of a monstrous figure who lives alone and plots to cancel Christmas celebrations for an entire town of joyful innocents. The Grinch remains, by and large, inscrutable, however — the purveyors of different Grinch projects have tried to find the reasons or motivations for why he endeavors to steal Christmas.

In Dr. Seuss's original 1957 book, no reason for The Grinch's grinchiness is given, a notion upheld in the 1966 TV special adaptation. That story is a short one, and when adapted into the feature-length, live action "Dr. Seuss's How the Grinch Stole Christmas" in 2000, filmmakers suggested a link between the Grinch's tough childhood and his hatred of Christmas — he was abandoned and bullied in holiday-obsessed Whoville. In the 1982 TV special, "The Grinch Catches the Cat in the Hat," it's explained that the character's resentment of Christmas stems from tragedy and trauma — his mother died when he was young, which left him permanently sad and mean.