Belfast Review: The Troubles Of Childhood

We're at a strange period in Kenneth Branagh's career. Introducing himself to the world as the director and star of several major Shakespeare adaptations, the filmmaker has found himself becoming more synonymous with underwhelming director-for-hire gigs in Hollywood. His take on "Henry V" bagged him Oscar nominations for his work on both sides of the camera. Just over 30 years later, his latest film, a project holding the poisoned chalice that is being this year's awards season frontrunner, falls between an "Artemis Fowl" adaptation with a single-digit Rotten Tomatoes score and a Poirot sequel causing headlines thanks to the controversies surrounding several members of the ensemble. He may be capturing critical attention once again, but within his filmography, his latest still finds itself in the shadows of the anonymous, derisively received films he has increasingly made his bread and butter.

Which is something of a shame, as "Belfast" is his most resonant work in years, a movie oozing warmth but resisting cheap sentimentality at every turn. Many critics have already had their knives out for the film (a time-honored tradition for any film unfortunate enough to be the Best Picture favorite), and understandably so. Upon finding out the film was a comedy, I naturally worried this would be an insufferably quirky coming-of-age story set against a bleak backdrop — "Jojo Rabbit" relocated to Northern Ireland at the height of the Troubles. Thankfully, the way Branagh finds levity within this child's-eye view of one of the darkest chapters in the country's recent history has far more in common with a film like John Boorman's 1987 film "Hope and Glory." It's a director recapturing some of the most pivotal moments of his childhood, without ever overlooking the grit that helped shape many of them.

Coming of age in a civil war

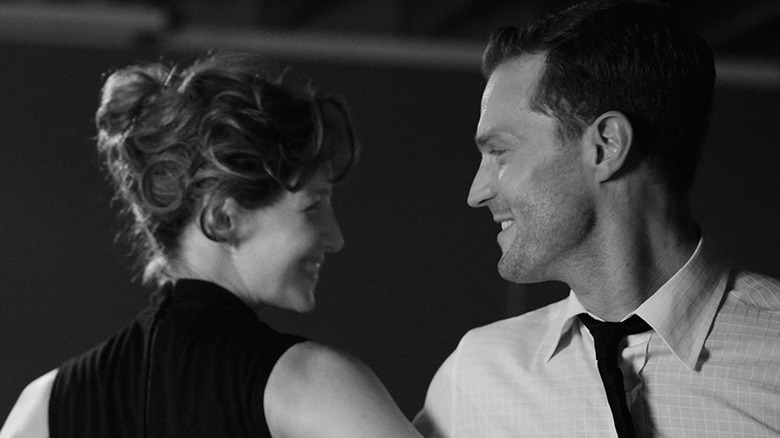

Naturally, the film is a semi-autobiographical one for its director, who relocated from Belfast to southern England as a nine-year-old. His big-screen avatar is Buddy (played by newcomer Jude Hill), who we're introduced to playing in his mixed neighborhood of Catholics and Protestants, seconds before rioting protestants arrive to vandalize the homes of his catholic neighbors. As we're seeing the drama from a nine-year-old's perspective, don't expect any larger insights into this turbulent period beyond this simplification of cultural tensions in the country — a choice that has provoked some ire, even if it's still approached with sensitivity. As Buddy sees his neighbors forced into turning against each other, his Protestant family (Jamie Dornan and Caitríona Balfe as his parents, and Judi Dench and Ciarán Hinds as his grandparents) make a stand against the division, refusing to see their friends and neighbors as anything less than equals. But the violence only continues, leaving Buddy's father to desperately look wherever he can for an escape route.

While many of the real harrowing events have been softened for the big screen, they remain unnerving precisely because of the more relatable coming-of-age story they're contrasted against. This is where it is most clear Buddy is Branagh's avatar, as we see him falling in love with theatre and the movies in pivotal experiences, as well as ticking off all the expected beats you'd expect from a character study set in this stage in childhood; first loves, school, and those first brushes with crime (aka: stealing candy from a shop) that are staples of youthful, mischievous behavior.

The approach to the subject matter may make some hesitant, largely because of just how sharp the contrast is between a harrowing tragedy and a more broadly comedic look at family life during the period. But this is exactly how the film reminded me of Boorman's Best Picture-nominated classic, a coming-of-age story set at the height of the WWII Blitz in London that found humor and optimism in the midst of hopelessness, all from a young pair of eyes that couldn't fully comprehend the scale of events around them. It's the lived-in memories of someone who now understands the full extent of the situation, looking back at how these factors he couldn't properly fathom were crucial to shaping the man he became.

Black and white and going for gold

People have been far quicker to compare "Belfast" to Alfonso Cuaron's "Roma," another black-and-white, personal tale set against the backdrop of devastating events. This comparison doesn't hold water beyond these surface level similarities, not least because Branagh has made a more populist crowdpleaser. Furthermore, several critics have already complained that Haris Zambarloukos' cinematography is nothing more than a gimmick to appear prestigious, taking inspiration from Cuaron's film without a deeper artistic purpose for its utilization. I couldn't disagree more, as Branagh inventively contrasts these visuals with color cinematography in several sequences, such as Buddy visiting the theatre to see a production of "A Christmas Carol." It's a straightforward visual motif to highlight the moments the director had his passion for creating art awakened as a child, but I found it effective nonetheless.

The film is far from flawless — a soundtrack comprised entirely of numbers from vocal anti-vaxxer Van Morrison proves to be jarring in every scene with a needle drop, the jaunty Celtic folk and soul numbers clashing with Branagh's more considered approach to depicting the period. And his attempt at an unsentimental approach, cutting between scenes as if leafing through pictures in a scrapbook, does mean many sequences just abruptly end before we arrive at the next vividly recreated memory. Although I'm not as critical of this as some others are, it does mean there are several moving moments ever so slightly undercut by a director not wanting to overplay his hand, detracting from powerful scenes in the character drama he's more than earned the right to linger on. It's easy to admire his directorial restraint, but in a film aiming to win over a broad audience, it seems like a minor miscalculation.

By the end, I was fully won over by "Belfast," an against all odds return to form from a filmmaker whose glory days seemed long behind him. At its best, it's a wonderfully realized portrait of childhood in a time of civil war, where the conventional coming of age experience is upended by forces far outside of your control. It's broadly moving, but never becomes saccharine, or cheapens its subject matter — which is more than you can usually say about the early Oscar season frontrunner.