The Most Iconic '80s Disney Movie Moments

Hey, did you know that Disney had an emo phase?

The 1980s were a unique period in the traditionally cheery studio's filmmaking history. It was a period marked with bold (and repeatedly unsuccessful) creative risks, a noticeably more adult tone, and a creative funk that wouldn't waft out of the air until the end of the decade. At the time, younger audiences were seeking more sophisticated, edgy entertainment. To keep up with public tastes, the House of Mouse adopted an approach that resulted in unusually dark films, at least by the studio's standards.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the company was still reeling from the death of its founder, Walt Disney. Walt's son-in-law, Ron Miller, took over. Per James B. Stewart's excellent, exhaustive book "DisneyWar," he repeatedly clashed with other executives about the company's creative future. There was clear frustration on Disney's part that they couldn't quite crack the lucrative demographic flocking to the likes of "Return of the Jedi" and "Ghostbusters."

The result of the company's crisis was a string of films that frequently flirted with horror, moody fantasies, and more grown-up themes. In the 1980s, the bulk of Disney's output carried a subtle sense of menace; a hard edge that lacked a single definition but still left a lasting impression on those exposed to it. The most iconic moments in Disney's 1980s output reflect this dark tone, from singularly nightmarish characters and haunting third acts to boundary-pushing experimentations in emerging digital technologies.

Enjoy this look at the most exemplary and memorable moments from Disney films from the 1980s.

Popeye (1980): He Needs Me

1980's "Popeye" was a warning of sorts; the first shot fired in a decade full of weird, risky, and implacably sinister films. Directed by the infamously subversive New Hollywood visionary Robert Altman, the musical comedy sought to bring E. C. Segar's comic strip of the same name to the big screen. With its bloated production costs and uncanny valley-courting prosthetics, the troubled production and its hostile critical reception effectively banished Altman to France, despite its commercial success.

In the intervening years, one of the key elements of the re-appraisal of "Popeye" was Shelley Duvall's performance as Olive Oyl. Not only does Duvall hold her own against co-star Robin Williams (whose turn as Popeye is arguably one of the actor's hammiest roles, which is saying something), she gets the best song in the film. Duvall's solo rendition of "He Needs Me" is a sweet and dreamlike testament to her and Popeye's touch-and-go courtship. It's also one of the few welcome breaks in the film's madcap pace, frenzied pratfalls, and audio-visual chaos.

While Popeye frets about being thrust into the deep end of parenthood, Olive skips around the docks of Sweethaven in a euphoric moment of clarity: someone needs her. Written and composed by singer-songwriter Harry Nilsson, "He Needs Me" persists as the most enduring musical element of "Popeye." Heck, Carly Rae Jepsen released a remix in 2019. How much more iconic can you get?

Dragonslayer (1981): Vermithrax's lair

The second joint production between Paramount and Disney, "Dragonslayer" fits snugly alongside the glittery, armor-clad swath of sword and sorcery films that populated the decade. The key difference between the 1981 film and its sword-wielding peers was that "Dragonslayer" was created under the auspices of the House of Mouse. As such, the nudity, disembowelment, and multiple virgin sacrifices probably came as a bit of a shock to unassuming parents. Then again, it was the '80s. Were parents really keeping that close of an eye on their kids?

"Dragonslayer" is what happens when Arthurian myth and teen rom-coms get in a fender bender. Written and directed by noteworthy American New Wave contributor Matthew Robbins, "Dragonslayer" does what it says on the tin. The film tells of Galen (Peter MacNicol), a young, impetuous sorcerer's apprentice who finds himself tasked with slaying a 400-year-old dragon named Vermithrax Pejorative (no, really).

Much of the film is a delicate balancing act between medieval whimsy and abject terror, which is how you know it's a good fantasy film. As far as edge-of-your-seat thrills go, nothing beats Galen's quest into the dragon's lair. Though armed with enchanted weaponry, Galen's expedition to rescue Princess Elspeth and slay the dragon is unsuccessful. If only all failures were this spectacular: the dragon, realized by stop-motion wizard Phil Tippett and Industrial Light and Magic, is an astounding combination of cutting-edge go-motion and to-scale animatronics. The jaw-dropping fire effects are just the (smoldering) icing on the cake.

The Fox and the Hound (1981): The bear attack

Loosely based on Daniel P. Mannix's 1967 novel of the same name, the animated feature film tells the story of an unlikely friendship between a feral red fox named Tod and a hunting dog named Copper. As the two grow up, they struggle to preserve their friendship as emerging animal instincts and social pressures attempt to force them to be adversaries.

"The Fox and the Hound" marked a critical turning point for the studio's animation division. It was the last film with any hands-on involvement from one of Disney's "Nine Old Men," and it was also the first major Disney project of future heavyweights including Tim Burton, Brad Bird, and John Lasseter.

As Vincent Canby astutely notes in his contemporary review for The New York Times, "The Fox and the Hound" features "a climax that could very well scare the daylights out of the smaller tykes in the audience, though all ends well." Indeed, the final moments of the film, in which Copper and his owner hunt Tod and his girlfriend, Vixey. During the hunt, Copper and his human inadvertently provoke a bear, who threatens the lives of everyone involved. When the bear almost kills Copper, Tod fights back. When Copper finds Tod incapacitated after the brawl, he stands between his old friend and his owner's gun. It's an on-the-nose moral lesson about prejudice, and if you watched that scene as a kid, it's seared into your memory.

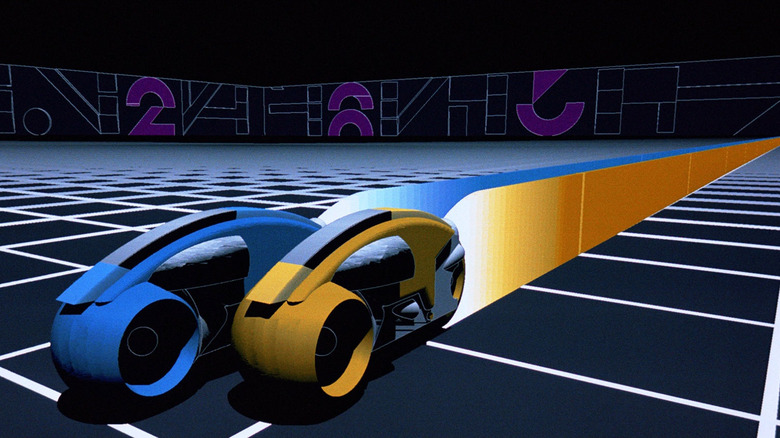

Tron (1982): The light cycle race

Steven Lisberger's sci-fi action-adventure film was one of the first films to use extensive CGI, which makes sense, considering the film takes place almost entirely inside a computer program. The film follows Kevin Flynn, a software engineer intent on proving that his former employer plagiarized his video game designs. In his quest to hack into the mainframe, which has developed into a power-hungry AI, Flynn finds himself inside cyberspace. There, he is forced to participate in deadly gladiatorial games reserved for divergent programs. In one of the most memorable scenes in the film, Flynn is forced into a light cycle match. Flynn and his digital competitors ride futuristic two-wheeled vehicles that emit solid blocks of light in their wake. The goal, naturally, is to force your competitors to smash into your trail and to remain the last man (well, computer program) standing.

The "Tron" light cycle match may look like a glorified screensaver today, but back in 1982, this sequence was groundbreaking. (Fun fact, the film was disqualified from receiving an Oscar nomination for its visual effects because the Academy felt that the use of computers was "cheating"). From the clean lines of the trailing light beams to the electric whir of each hairpin turn, the light cycle battle left its mark on science fiction, no matter what the Academy says.

Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983): The hall of mirrors

Look, if American novelist Ray Bradbury is involved, you know things are going to get weird. Directed by Jack Clayton and written by Bradbury himself — adapting his own 1962 novel of the same name — "Something Wicked This Way Comes" is a dyed-in-the-wool nightmare. A diabolical circus descends on a small American town, granting wishes for the townsfolk only to twist their deepest desires in the most nefarious ways possible. It's up to two young boys, Will and Jim, to face the circus' devilish ringleader, Mr. Dark (Jonathan Pryce) to save their town.

In the film's climax, Will's gray-haired father, Charles (Jason Robards), follows the two boys into a hall of mirrors. It is a scene ripped straight from a night terror. Disoriented, Charles frantically paws his way through the maze, searching for the children as Mr. Dark taunts him endlessly about his age and inevitable death. Fog swirls at his feet and visual reminders of his fleeting life play out between reflections of his wrinkled face. "Something Wicked This Way Comes" is ultimately a morality tale about how we should value the present over both the past and the future. This moment drives home the stakes of this thesis with unsettling and unforgettable clarity.

The Black Cauldron (1985): The army of the undead

Say what you will about "The Black Cauldron" (and trust us, there's a lot to say), but Disney deserves credit for taking a big ol' risk. The film was the first Disney animated feature to receive a PG rating, as well as one of the first Disney animated films to feature CGI. At the time, with a budget of $44 million, it was the most expensive animated film ever made. Turns out throwing that kind of money at a fantasy epic isn't exactly a safe financial gamble. The film bombed at the box office, securing its infamy as the rock-bottom of Disney's post-Walt dark ages.

In an ironic twist, the quality that condemned "The Black Cauldron" as a failure is also what makes it so distinct: Namely, the off-brand decision to take Disney animation into dark, morbid, even slightly violent territory. Disney hoped the tonal shift would attract the coveted teenage market (it didn't). Instead, early whispers of the film's intensity and scariness frightened away Disney's core audience of kids and their parents. In a cruel (or at least darkly amusing) twist of fate, nowadays it's the film's darker elements that keep it humming in the cultural conscience.

The most memorable and enduring part of "The Black Cauldron" is its loads and loads of skeletons. Bony warriors decked in rotting leather, dented armor, and residual sinew are the invincible product of the titular jet-black cauldron. The undead army arrives just when all hope seems lost, with our heroes captured and the Horned King's nefarious plot well within his grasp. It's the darkest moment in a film defined (for better and for worse) by its darkness. If that ain't iconic, we don't know what is.

Return to Oz (1985): Wheelers

You may have noticed that more than a few entries on this list qualify as bona fide nightmare fuel. But nothing, and we do mean nothing, can compete with the Wheelers in "Return to Oz." An unofficial sequel to the 1939 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer classic, the 1985 Walt Disney Film is a more accurate adaptation of Frank L. Baum's "Oz" novels — which also means that it is absolutely terrifying. While the electrotherapy (for kids!) and whatever in god's name "The Gump" is are unsettling in their own right, the Wheelers are a whole other can of worms.

The Wheelers are this film's answer to the Winged Monkeys: mischievous minions of the head-stealing Wicked Witch Mombi. With wheels where their hands and feet should be, the Wheelers are maniacs all too happy to carry out Mombi's every whim. When Dorothy Gale returns to the now-conquered Oz, she finds the Emerald City in shambles, with all its residents turned to stone. As if seeing a former place of magic reduced to rubble wasn't upsetting enough, the Wheelers show up to terrorize poor Dorothy (and the cowering audience). These psychotic and unnervingly speedy henchmen are what we think of when we think of one of Disney's darkest offerings.

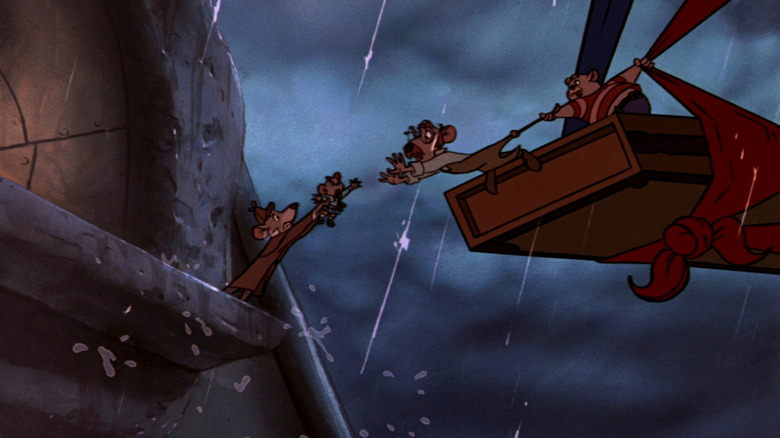

The Great Mouse Detective (1986): Clocktower finale

If "The Black Cauldron" was the film that almost killed Disney animation, "The Great Mouse Detective" was the film that saved it — or at least kept it above water until co-directors Ron Clements and John Musker's follow-up, "The Little Mermaid."

The movie was based on Eve Titus' series of children's books, "Basil of Baker Street." Like its source material, "The Great Mouse Detective" draws heavily from the adventures of famed fictional sleuth Sherlock Holmes. Set in late 19th-century London, "The Great Mouse Detective" sees detective duo Basil of Baker Street (Barrie Ingham) and Dr. David Q. Dawson (Val Bettin) on the hunt for a kidnapped toymaker. A chance run-in with the toymaker's daughter Olivia leads Basil to deduce that his nemesis, Professor Ratigan (Vincent Price), is up to something nefarious.

In the film's nail-biter finale, Ratigan and Basil crash their respective aircraft into the Big Ben clocktower. While Ratigan continues to hold tiny Olivia hostage, Basil chases his nemesis through the cavernous clockwork. It's an intense, high-stakes face-off in one of the most iconic landmarks on the planet, rendered all the more menacing and grand with the still-novel use of CGI backgrounds. And the dramatic, rain-swept, brawl on the slick hands of Big Ben's clock? Incredible. No notes.

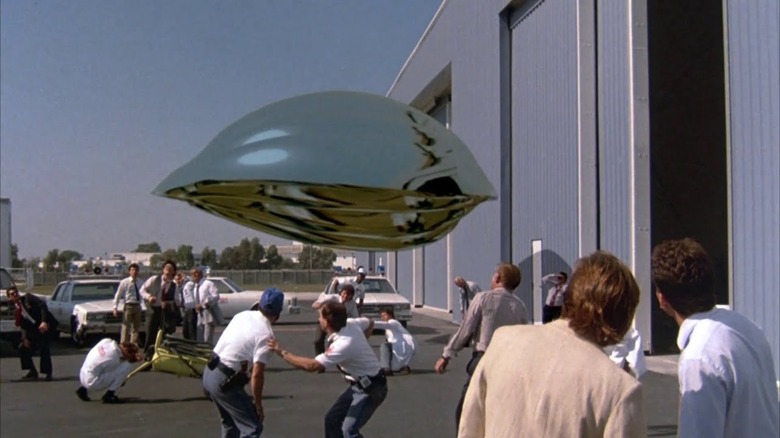

Flight of the Navigator (1986): The CGI spaceship

Plenty of Disney films in the 1980s broke new ground for CGI effects. One of those films was 1986's "Flight of the Navigator," a sci-fi adventure whose alien subject matter proved fertile ground for all manner of special effects showboating.

"Flight of the Navigator" tells of David Freeman (Joey Cramer), a 12-year-old boy who is knocked unconscious after falling into a ravine near his home in Fort Lauderdale. When David finally comes to, eight years have passed and he hasn't aged a day. When an alien spaceship crashes nearby, doctors, scientists, and David himself begin to suspect that his disappearance and the UFO are connected.

Sleek, chromatic, and thoroughly out of this world, the Trimaxion Drone Ship absolutely deserves its spot on this list not only as an iconic sci-fi vessel, but also a notable technical achievement. Created by Omnibus Computer Animation, "Flight of the Navigator" was the first film to use reflection mapping to create realistic (for the time) reflections on a simulated chrome surface. The UFO's unique look is the clear highlight of this childhood staple turned cult flick.

Oliver & Company (1988): The death of Sykes

For obvious reasons, Disney tries to stay away from on-screen deaths in its animated films. There is, however, one consistent exception: you can pretty much always expect villains in animated Disney films to die horribly. The Evil Queen in "Snow White" falls off a cliff and is crushed by a boulder. Maleficent gets stabbed through the heart and falls to her death. Gaston also falls to his death, and Judge Frollo too. There's a lot of falling to one's death, okay?

We're used to seeing animated Disney villains bite the dust. But there's something especially jarring and brutal about the demise of Bill Sykes (Robert Loggia), the immoral loan shark and primary antagonist of "Oliver & Company." Based on Charles Dickens' novel "Oliver Twist," the Disney film tells of an adorable, homeless kitten who joins a gang of rough-and-tumble New York street dogs while Billy Joel songs blast in the background.

In the film's final act, the bumbling shenanigans of the pickpocket Fagin (Dom DeLuise) stoke Sykes' ire. A chase ensues, and the vehicular chaos suddenly careens into the New York subway tunnels. After Sykes' two Dobermans are electrocuted (!) on the subway line, our heroes are mercifully thrown out of harm's way before Sykes is struck and killed by an oncoming train. Maybe it's Sykes' white-hot murderous intensity or the way his pupils constrict in sheer terror in the bright light of the train's high beams, but good gravy, that man getting pancaked by a subway is one of the wildest things Disney has ever done.

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989): Antie

Joe Johnston's "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids" has a whimsically literal title: The plot follows what happens after an eccentric inventor (Rick Moranis) accidentally shrinks his children. As you'd expect, being shrunk down to a quarter of an inch turns even the most mundane things into huge hazards.

But hey, being small does have its advantages. A humdrum oatmeal creme cookie becomes a veritable feast when you're little enough. After miraculously surviving their backyard (which, from their point of view, is a jungle), the kids are thrilled to finally find what is, let's be real, every kid's dream: a cookie that is bigger than you. Enter Antie, the worker ant who interrupts the kids' meal only to become their very best friend, following, protecting, and even sacrificing themselves for the tiny children. Antie, you're a disturbingly moist-looking, hairy legend. You made a whole generation of kids think of ants from a different perspective.

The Little Mermaid (1989): Poor Unfortunate Souls

"The Little Mermaid" represented a pivotal shift in Disney's animated output, kicking off the "Disney Renaissance." A key element of the film's success can be attributed to Alan Menken and Howard Ashman, the creative team behind the film's music. Menken and Ashman were noted for their work as the writers of the enormously successful stage musical "Little Shop of Horrors." The pair brought their Broadway sensibility and lyrical flair to the film's musical sequences.

Nowhere is this more apparent than the villain song of Ursula, the sea witch. "Poor Unfortunate Souls" is, effectively, a drag number, allowing Menken and Ashman's familiarity with the New York queer scene to shine (indeed, Ursula's character design was based on the legendary drag queen Divine). As Ursula details the essential service she provides to those in desperate need of her witchy ways, she uses her eels like a feather boa, chews the scenery like it's made of ham, and is, in a word, iconic. "Under the Sea" can take a hike. "Poor Unfortunate Souls" isn't just the best song in "The Little Mermaid"; it's one of the all-time best Disney songs, period.