Questionable Things We Ignore In The Mummy

"The Mummy" is one of those movies you can watch any time. It's exciting and funny, and it stars some incredibly charismatic actors at the peak of their powers: Brendan Fraser, Rachel Weisz, John Hannah, Arnold Vosloo, Oded Fehr, and plenty of others. It changed the action movie game for the better. It even has one of the all-time best movie romances: Rick and Evy forever! And on top of all that, the CGI still holds up surprisingly well.

But because "The Mummy" is so great, it's a very re-watchable film ... and eventually you're bound to notice a few things that may have been initially brushed aside in the throes of appreciation. Some of them are just ordinary plot holes and nitpicks — others are more troubling aspects, more visible now than they were when the action blockbuster hit theaters in 1999.

Even if there are a few spots that might raise some eyebrows, that doesn't detract from one of the best action films of its decade. Sure, "The Mummy" has its faults, but audiences can simultaneously acknowledge them and still appreciate the finished product. Here are some aspects of "The Mummy" — both big and trivial — that you have to get past if you really want to strap in and enjoy the ride.

Colonialism hangs over everything

From a contemporary vantage point, it's hard to watch "The Mummy" without noticing the specter of colonialism: The movie literally wouldn't happen if the English and American characters didn't reflexively feel that it was their right to go to Egypt and do whatever they wanted.

Evy (Rachel Weisz) and Jonathan (John Hannah) are reportedly part-Egyptian, via their mother, but they're played by white English actors using English accents and clearly "read" as essentially English. Like many characters in the franchise, they see the riches of Egyptian civilization as being largely a thing of the past — and a culture that is a free-for-all, to be acquired and be sold by whoever happens to get to it first. Imhotep's rise acts partly as a commentary on all that: When you blunder into a culture and history you don't fully understand, you can unleash more than you intend to.

You can also see the lingering presence of other empires' interference in the histories of Rick (Brendan Fraser) and Winston (Bernard Fox); the former first comes across Hamunaptra when he's serving in the French Foreign Legion, and the latter is a former British officer hanging around in Egypt because he misses the daring battles of his glory days. Egypt isn't quite home — it's a place where you're supposed to have colorful, dangerous adventures that take you out of your ordinary life. And for just about all the white characters, Egypt mostly exists as a playground, where you can establish yourself and potentially make your fortune.

Cursing Imhotep was an awful idea from the start

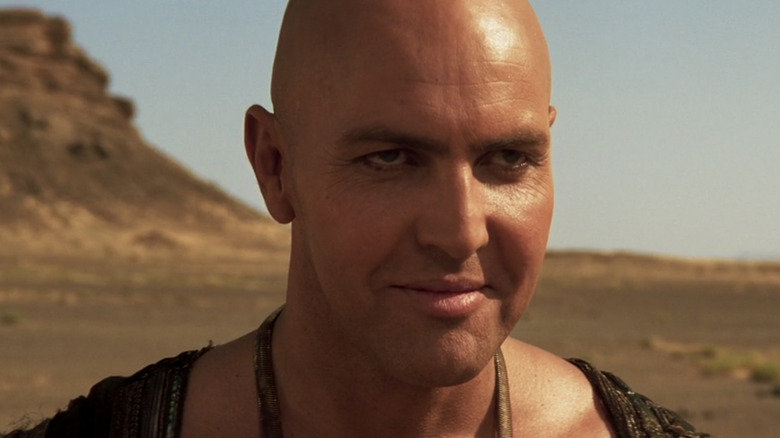

It's great that the Medjai dedicated their lives to making sure Imhotep (Arnold Vosloo) didn't rise from the dead; for thousands of years, they kept the mummy's curse at bay. But all of this could have been avoided if their ancient predecessors simply hadn't used the dreaded Hom-Dai curse in the first place.

Imhotep's priests were mummified alive too — isn't that punishment enough? Did someone really need to include flesh-eating scarabs and serious magic to make Imhotep's death just a little bit worse than it would be already, when the consequences could be so dire?

If you have two means of slow, gruesome, and painful execution to choose from, it seems that you should always choose the one that can't potentially backfire and give your enemy immortality, invincibility, and a destiny to destroy your country (and possibly the world). Honestly, why risk it? For years, everyone apparently dreaded the Hom-Dai too much to actually use it — and that was definitely the smarter, safer course.

Most of the Egyptian characters are punchlines

"The Mummy" certainly supplies several vivid and prominent Egyptian characters. Oded Fehr's Ardeth Bay is skilled, charismatic, mysterious, and even funny — one of the best little grace notes in this movie is his total glee at getting to ride on the wing of Winston's airplane. Imhotep is a compelling, well-motivated villain with terrific screen presence. Even Dr. Terence Bey (Erick Avari), the museum curator (and secret Medjai) who is Evy's beleaguered supervisor has some great scenes.

But it's hard to avoid the fact that a lot of the other Egyptian characters are basically jokes — and those jokes often have a nasty racial component. The Warden (Omid Djalili) is the unwanted travel companion who is constantly the butt of the movie's humor; it's particularly uncomfortable that Jonathan keeps saying that he smells bad. Even his death by flesh-eating scarabs, which sounds horrific in theory, hits like a comedic beat, since the main characters only see what's happening when the Warden comes tearing into the room and runs smack into a wall, seemingly killing himself. When Imhotep's return to life and power seemingly convinces most of Cairo to go along with him, their mass mumbled chanting and lifeless shambling seem like a visual gag: They're essentially zombies.

It's great that the movie boasts some bold, interesting characters of color. It's just unfortunate that some of the supporting characters — especially the ones portrayed en masse — fall into ugly stereotypes.

That's some really long-lasting papyrus

Nobody should quibble too much about the technical details in a film that includes mummies, resurrection spells, and ancient curses ... but seriously, the map to Hamunaptra is still intact after more than 3000 years?

Actually, that isn't as unlikely as it may seem. The University of Michigan's Papyrus Collection explains that thousands of bits of Ancient Egyptian papyrus have survived into the modern day, thanks to the arid Egyptian weather. While the paper might decay quickly in more humid environments, it's much safer in the desert. But if you've raised your eyebrows at that pristine map, your suspicions weren't completely unfounded; there's a little bit of Hollywood clean-up going on here. Papyrus documents have survived into the present day — up to 4500 years, in the oldest cases — but they don't tend to be in such sparkling condition. These tattered, fragmented examples from the Metropolitan Museum of Art are more typical.

Shouldn't Imhotep be nearsighted now?

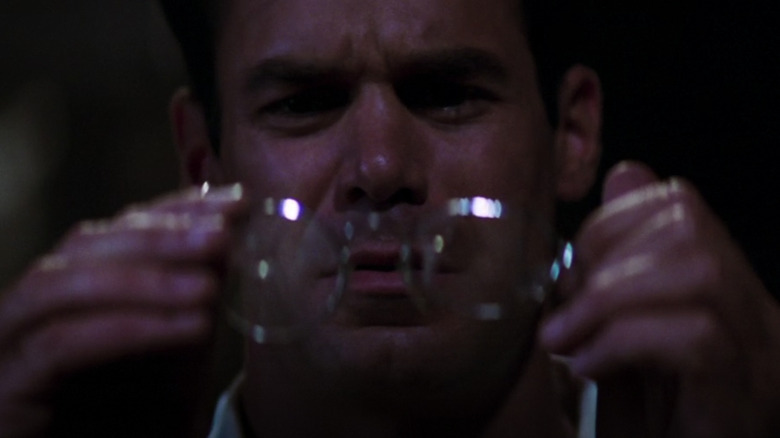

Uncharacteristically, when Imhotep takes poor Mr. Burns' eyes, "The Mummy" misses the chance for a great — if slightly cruel — gag. Burns (Tuc Watkins) says early on that without glasses, he couldn't even see well enough to play cards ... and when his glasses get broken in the mad scramble after Imhotep rises, we see that he wasn't exaggerating. His view of the world is a blurry mess.

Of course, Burns' vision is about to get even worse: Imhotep rips out his eyes and tongue to replace his own, kickstarting his journey back to life. The film only shows the aftermath, but it's surprisingly harrowing. It also inevitably raises a big question: If Imhotep took Burns' eyes, shouldn't he have Burns' terrible, swimmy vision? A cursed mummy who's barely able to see his own crumbling hand in front of his decaying face is exactly the kind of comedic beat "The Mummy" would usually like, so it really feels like a scene got lost here.

The best the audience gets is a hint, not a full-on plot point. While Imhotep is getting used to his new eyes, he squints at Evy (Rachel Weisz), which feels like a nod to Burns' poor eyesight. But it's not quite enough payoff, after all that great set-up. Oh well, sucking the life out of a few more members of the resurrecting party would most likely sharpen his vision permanently, so nearsighted Imhotep was always going to be a short-lived phenomenon anyway.

Free will isn't really a factor

What makes Imhotep evil? From a modern-day standpoint, it's hard to condemn the fact that he slept with the Pharaoh's mistress: Imhotep and Anck-su-namun were genuinely and passionately in love, while the Pharaoh seemed to only treat her as property. Even though it's almost always a bad idea to dabble in resurrection magic, Imhotep's initial quest to bring Anck-su-namun (Patricia Velásquez) back to life feels like a grand romantic tragedy, not the beginning of serious villainy.

But when he comes back from the dead, he's just cruel. He seems to take pleasure in causing fear and suffering, and his ultimate plan is to take control of the world. Why did he escalate like that?

Answer: the Hom-Dai. The curse that was inflicted on him didn't just give him the potential for superpowered resurrection — it fated him to bring about death and even all the plagues of Egypt. In essence, the Hom-Dai dooms the world partly by taking away Imhotep's free will. He literally can't change his mind and decide to pursue another course of action.

Our heroes take other people's deaths in stride

"The Mummy" is rollicking good fun and a total delight of a movie — but part of what makes it so ceaselessly enjoyable is that it never really dwells on any of the carnage that happens along the way. That works well for the movie's tone, but after a certain number of rewatches, it's hard to not notice the lead characters are pretty blithe about all the deaths happening around them. When the Warden — admittedly not a friend, but at least a member of their own expedition party — dies, they're not shaken so much as confused. Within minutes, Jonathan (John Hannah) is cracking a joke at the Warden's expense; within an hour or two, Rick and Evy are having a flirtatious interlude by the fire.

The same lack of emotional response is present when the American expedition team starts dying off, as well. At this point, our heroes have interacted with these people a fair amount, both on- and off-screen, and you might expect them to feel something about it. Or you might think they would feel wrenching guilt at having inadvertently kickstarted Imhotep's devastating reign of terror. In both cases, not so much.

It's all just a side-effect of trying to tell an adventure story that combines non-stop entertainment with high stakes and a sense of danger. Sometimes you have to ignore a few deaths, in the name of having a good time.

Everybody's a grave-robber

How long does someone have to be dead before it's okay to rob their grave? This is an awkward question that you might now want to throw into any random conversational lull, but it's also something to think about while watching "The Mummy." After all, all the main characters kick off the action by infiltrating a notoriously forbidden gravesite and excavating a corpse. Some of them are hoping for treasure, and others — more purely motivated — are just hoping for knowledge. But all of them are trespassing on a sacred cultural site and disturbing a grave. Is that really the proper, heroic thing to be doing?

Honestly, the outcome of events in "The Mummy" suggests that it's probably not. Yes, the lead characters eventually escape healthy, whole, and in possession of plenty of treasure and sequel potential ... but look at what they had to go through to achieve that happy ending, and look at how many of their fellow historical grave-robbers got lost along the way.

Imhotep's powers are horribly ill-defined

The Hom-Dai guaranteed Imhotep the power to summon the plagues of Egypt, and even before his death, he was already skilled in the art of resurrection. And the life-sucking abilities that let him take on new body parts and eventual immortality also seem closely tied to the original curse. But where do the sandstorms come from?

When Winston is flying Rick, Ardeth Bay, and Jonathan in to try to rescue Evy, Imhotep does some impressive glowering, conjuring up a massive storm to try to knock the plane out of the air. It's sort of a callback to something that happens when Rick — still in the French Foreign Legion — first came across Hamunaptra: He witnesses random bursts of sand flying into the air, and eventually, it all seems to form a giant, despairing face. It's a great visual, but when you stop to think about it, why is Imhotep a master of the sand ... and why can he control it when he's still technically dead? Or, why he would want to, when phenomena that drive people away from his burial site could actually wind up preventing his resurrection.

He can also turn into sand, pouring through a keyhole and even whisking himself away in a sudden flurry of wind. Again, it's a cool effect. But where does it come from?

Whatever happened to the last plague?

The prophecy predicts that a revived Imhotep will bring the return of the ten plagues of Egypt. Most of them hit quickly: All the water turns to blood, flies and frogs swarm, boils strike most of the population, and an eclipse blots out the sun. We see most of it on-screen, and can guess that more is happening elsewhere. But the plague progression still leaves the viewer with some unanswered questions.

For starters, why doesn't the main cast get affected by things like the plague of boils? Evy and Jonathan are both half-Egyptian, and in "The Mummy Returns," we find out that Rick is actually descended from the Medjai. All of them — including Winston, the pilot who helps them — have apparently lived there for years. Shouldn't they be getting hit by all of this?

But the biggest issue is with the tenth plague: the death of the firstborn sons. The movie never mentions this one, even though the looming specter of it could provide some amped-up third act stakes: What if they had to race to stop Imhotep, partly to keep this plague from devastating Egypt and potentially killing Jonathan, the source of comedic relief? Instead, it just never comes up, making for an odd plot hole.

Egypt bows to Imhotep with record-breaking speed

A sudden rash of plagues might convince people of a lot of things. Perhaps they could shrug off a sudden infestation of frogs, but it's harder to rationalize all the water suddenly turning into blood. But even though it's easy to understand why the modern Egyptians in "The Mummy" immediately believe that Imhotep's return is a serious issue, it's a little amazing that so many people immediately convert to Imhotep-worshipping zombies. Shouldn't more people should be trying to take this guy out?

At the very least, it's surprising that so many people not only fall in line, they take to the streets as a mob chanting the name of the new boss. It's especially weird because it's hard to know how Imhotep rallied all these followers in the first place. Was Beni (Kevin J. O'Connor) hitting the street corners and explaining the situation? Why would anyone believe him? Did they have to get a look at Imhotep's half-eaten-away face before they were convinced? Or was the legend of Imhotep and the Hom-Dai just that well-known to native Egyptians?

Of course, this could all make sense. Any of these explanations seems semi-plausible. But it's a lot to have happen off-screen, and it unfortunately continues the movie's pattern of ignoring almost everything that happens with its Egyptian characters.

For a fun action-adventure movie, it's startlingly dark

The 1932 Boris Karloff version of "The Mummy" — which the 1999 "Mummy" very loosely remakes — was an out-and-out horror movie, and some of its chills remain in this otherwise cheerful, colorful update. This "Mummy" leans more towards old-fashioned adventure than horror, but it doesn't hesitate to incorporate more than a few skin-crawling scenes. Some of them are very dark, and even brutal.

For one thing, if you have a fear of being buried alive, the prologue is a torturous experience. Seeing Imhotep and his priests mummified alive and sealed into their coffins is bad enough, and the cruel cherry on top is the later revelation that Imhotep — despite being slowly eaten alive by scarabs — stayed conscious long enough to scratch a message into the inside of his coffin. Then there are the scarabs themselves: giant bugs that immediately burrow under your skin.

But the most wrenching scene might be the sad fate of Mr. Burns, one of Imhotep's first victims. As if it's not bad enough that the poor guy loses his eyes and tongue, he then has to unknowingly entertain his attacker. With bandaged eyes and awkward speech, clearly still getting used to his new injuries, he's clumsy, overwhelmingly grateful for company and kindness, and eager to be polite. When Beni reveals that "Prince Imhotep" is actually there to finish the job he started at the dig site, Burns' terror is devastating.