The French Dispatch Review: The Best (And Worst) Of Wes Anderson

Nothing in "The French Dispatch" is going to change your opinion on Wes Anderson. The director's latest film operates as a greatest hits package of his various stylistic and thematic impulses, although his approach to playing the classics is unlikely to win over many who weren't on board already. And as his latest is a triptych, he can dip in and out of the stories he predominantly tells at ease. There's the lovelorn teenage romanticism of "Rushmore" and "Moonrise Kingdom," the prison capers of "The Grand Budapest Hotel," and all the meticulously designed stylistic quirks of those films and every one that came in between. If you find his approach to storytelling off-putting, there's nothing I can say that will convince you to give him another chance — but even as someone who is usually warm towards his films, I found myself growing cold and distant rather quickly.

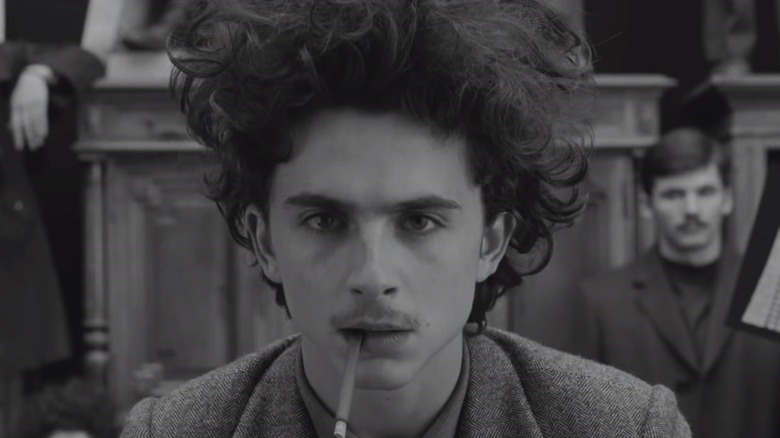

The director has stressed in interviews that the idea to make a triptych of stories set in France came long before he had any idea about what any of the narratives would be. And at times, it painfully shows, the New Yorker articles that loosely inspired each segment not always generating enough narrative intrigue to sustain interest. The middle section, a fantastical reimagining of the May 1968 protests, sees the director coasting on winking historical references, simplistic visual allusions to several French New Wave directors, and a blink-and-you'll-miss-it shot of Timothée Chalamet's penis. By the time we get to the finale, the second of two stories set in a prison despite having an entire fictitious city as a narrative playground, your patience is likely to be tested even more. It's a film where the limits of a seemingly boundless cinematic imagination are frequently exposed.

Hot off the press

The film is Anderson's love letter to journalism, and is dedicated to several former New Yorker writers he has created thinly veiled fictional surrogates for here. It's a typically niche source of inspiration for the director, who has been collecting vintage issues of the magazine since his teenage years, although it does help inform the initially ingenious structure. Set out like an issue of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, the triptych of stories at the film's center (designed as three "long reads" about various topics) are complemented by notes from the editor, smaller dispatches about life at the newspaper's French outpost, and an epilogue which confirms this is the publication's last ever issue.

The prologue first introduces us to editor Arthur Howitzer Jr (Bill Murray), the kind of supporting role Anderson can write for his most recurrent collaborator in his sleep. Inspired by New Yorker co-founder Harold Ross, Howitzer is a straightforwardly curmudgeon on the surface — a man with exacting demands for his publication, and even more so for the reporters he carefully hand picks to write for him. The energetic opening prologue, in which Anjelica Huston's narrator manages to accentuate the humor in what is otherwise the most expository moment in Anderson's filmography, is an inviting introduction to this world, almost immediately finding some warmth within a study of a man with a "no crying" banner above his door, who fires employees at will. The story, much like "The Grand Budapest Hotel," is initially framed in the past tense, an epitaph for a legend of journalism we are immediately told has just passed away. Anderson's reverential attitude towards him proves infectious because of this, with the opening moments managing to find a sense of melancholy within the madness, a profile not just of a man but of a commitment to the craft of journalism you suspect the director thinks is now a thing of the past.

It's when we leave the newsroom that his ode to the profession proves less than convincing. Travel writer Herbsaint Sazerac's (Owen Wilson) whistle-stop tour through the city of Ennui-sur-Blasé is an immediate high point, the segment most reliant on visual gags as it tries to cram an entire imagined history into the space of five minutes. This is the film at its funniest — although your reaction to the humor will likely depend on whether you rolled your eyes upon finding out the name of the city this film takes place in. After that, we settle into the three extended stories, where Anderson makes the critical error of leading with what is by far the strongest of all three.

Lost in the post

This story, entitled "The Concrete Masterpiece," also happens to be the segment of the triptych furthest removed from its real-life influences, feeling more joyously anarchic next to stories that struggle to balance their comedy with doting tributes to the people who inspired them. If other performers in the ensemble find themselves struggling to balance their comedic instincts with the director's required reverence towards writers from the New Yorker's golden era, Swinton embraces caricature. She narrates this segment while donning the customary wig and fake teeth that come out of the wardrobe seemingly whenever she signs on for a comedic role, with her reporter a fairly broad parody of a largely incompetent writer who seemingly got their job due to upper class connections.

It sharply contrasts with the playful story itself, in which incarcerated painter Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro) finds himself becoming a darling of the art world behind bars — only to infuriate those same critics when he drags his heels on exhibiting a new piece. In a film that lazily transitions between black and white and color at will, a surface level nod to French New Wave style, this segment is the only time this visual approach adds something to the story, routinely showing Rosenthaler's art and the limitations of inspiration behind prison bars in a new light.

We immediately follow the best chapter in the story with the weakest. "Revisions to a Manifesto" follows reporter Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand) as she profiles the student revolutionaries leading the protests that end up sweeping the entire nation. With this being a Wes Anderson film, the main cause of the protests here is students not being able to spend a night in the dorm rooms of the opposite sex — which leads to what is essentially a gallic retread of several stories about teenage kicks the director has told before, as Zeffirelli (Chalamet) aims to simultaneously consummate his relationship and bring about social change. It's in this segment that it becomes most apparent that Anderson had the idea of making a triptych set in France before knowing what any of the stories would be, and can't cover up treading familiar ground with his historical backdrop.

The final story, "The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner," is better, although this is entirely through Jeffrey Wright's performance as Roebruck Wright, an obvious surrogate for James Baldwin. In a film where it can often feel like several performers are getting lost within the ensemble, to the extent it feels like some are deliberately taking on thankless roles just to work with Anderson, Wright commands attention to the point where it becomes clear the chapter is only engaging because of him. This is the aforementioned second story set within a prison, and although the farcical kidnapping adventure is different from the earlier art world drama, it can't help but feel like a disappointment for how it returns the audience back behind bars. In smaller segments throughout, Anderson showcased a typically detailed history of the city, making it incredibly frustrating that we're kept from exploring it beyond brief interludes, the stories he chooses to tell serving only to make us wonder what is actually going on outside prison walls.

Ultimately, "The French Dispatch" showcases Wes Anderson at his very best and worst. One of his most lovingly designed films, featuring three stories that don't complement the grand canvas of a city he has created.