The Untold Truth Of BoJack Horseman

There are roughly six billion viewing choices at any given moment, so TV aficionados can be forgiven when a quality show or two slips under their radar. But if you've never seen BoJack Horseman, it's time to set aside your Shark Tank marathon, toss your preconceived notions gently out the window, and dig in to what many critics are calling the best show on Netflix. Which critics, you ask? The ones who aren't calling it the best show on TV, period.

It's incredibly dense with jokes

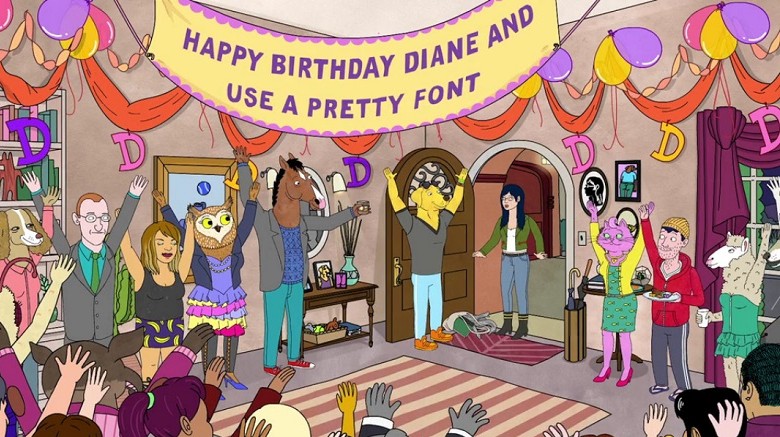

In the '90s, he was in a very famous TV show—but now he's just the washed-up former star of the cheesy sitcom Horsin' Around, about three orphaned kids raised by a horse. This isn't such an odd premise in BoJack's world, in which talking, anthropomorphic animals of all sorts live side by side with, work with, and even date and marry human beings. A great deal of comic mileage is gotten out of the quirks of various animal species, usually in the form of blink-and-you'll-miss-it background gags, but this is only one means by which the show's writers pack each episode to the margins with comedy.

For starters, there's usually a gag involved any time text is on the screen, no matter how briefly. Quick callbacks to past episodes—and, for that matter, call-forwards to future episodes—come at the viewer at a pace not seen since Arrested Development, and many seemingly throwaway jokes (such as BoJack stealing the "D" from the famous Hollywood sign) stick around far longer than you would expect (Tinseltown is thereafter permanently referred to as "Hollywoo"). The sheer volume makes it impossible to catch them all, making BoJack a show that demands—and rewards—repeat viewing.

The cast is stellar

Speaking of Arrested Development, BoJack is voiced to gravelly perfection by Will Arnett, who continually nails the series' constant shifts in tone (more on that shortly). In voicing BoJack's long-suffering yet relentlessly optimistic roommate Todd, executive producer Aaron Paul strays about as far as humanly possible from his portrayal of Jesse Pinkman in Breaking Bad, while Alison Brie and Paul F. Tompkins round out the core cast. These heavyweights are supported by the kind of regulars and guest stars that would make any casting director green with envy.

At one time or another, the cast has included: Angela Bassett, Mara Wilson, Fred Savage, Candice Bergen, Maria Bamford, Patton Oswalt, Stanley Tucci, Lisa Kudrow, J.K. Simmons, Olivia Wilde, Keegan-Michael Key, "Weird" Al Yankovic, and of course, character actress Margo Martindale—to name a few. Show creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg says of his cast: "There are actors who can do everything and make anything better. I feel like that's our cast... (they) know how to land a punchline, they know how to make the setup as funny as the punchline and they really get the emotional moments as well. They always knock it out of the park. It's such a joy to work with them."

The humor is really intelligent

On the surface, it seems like an animated comedy about talking animals should skew heavily towards silly humor. While many of BoJack's gags aren't afraid to embrace the goofiness—a woodpecker that can't keep from doing its thing, or a foxhole filled with actual foxes, for example—its best jokes reward a deep knowledge of pop culture, and the show revels in setting up viewers' expectations so it can gleefully subvert them. Even if you know there's a punchline coming, it's probably not the one you were expecting.

This is perhaps best illustrated by the frequent appearance of character actress Margo Martindale, who is never referred to without that descriptor and is voiced by the actual Margo Martindale. BoJack frequently enlists her acting talents to help him carry out ill-advised schemes, culminating in having her carry out an armed bank robbery, after which she's MIA for several episodes. When she reappears, she explains she's been hiding out among the cast of The Good Wife, having just completed a season-long stint. When asked how she could possibly hide out on a nationally broadcast TV show, her answer is dead simple: "I disappeared into the role. It's called acting, BoJack. You should try it sometime."

It's the Hollywoo(d) satire we all need

BoJack Horseman has a lot more on its mind than endless gags. But at its heart, it's a brilliant satire of Hollywoo(d) culture, or lack thereof. When it comes to the endless cycle of entertainment news, the shallow and fleeting nature of celebrity, and the creative bankruptcy of the Hollywood dream factory, BoJack is not afraid to cut—shallow, deep. and everywhere in between.

Examples of the former are almost too numerous to mention, such as the hosts of an E-News type program being referred to only as "A Ryan Seacrest Type" and "Some Lady" (who is occasionally replaced by "An Actress or Something, I Don't Know"). But many of the show's longer story arcs point out the deep underlying superficiality of Tinseltown, as when BoJack is nominated for—and convinced by his agent that he deserves—an Oscar for a performance that was entirely replaced by CGI in post-production. BoJack's attitude toward Hollywood is summed up nicely by agent Princess Caroline in a season 2 episode, as she attempts to convince "reclusive" author J.D. Salinger to return to television. When he laments that he's tired of getting hassled about his books ("well... book"), Princess Caroline replies: "What if I told you there was a place where nobody reads books? A place where people only read headlines, lists and pictures... a place where people hate reading so much, they hire others to do it for them, and don't even pay them a living wage!"

It's super dark, but not without purpose

It's been said by more than one critic that if BoJack Horseman weren't so colorful and inventive, it could easily qualify as the saddest comedy of all time. BoJack struggles constantly and mostly unsuccessfully with the darker aspects of his nature, and while this isn't new ground for a comedy series, the way in which BoJack uses its darker moments to explore human nature is singularly unique.

To put it bluntly, BoJack is a mess. He craves approval and understanding, yet has no idea how to ask for those things in any kind of straightforward fashion; he sabotages himself constantly, is allergic to responsibility, and is only drawn to self-reflection when it looks as though an important relationship might actually be doomed. Yet he isn't given these qualities for the sake of broad humor; for all of his faults, BoJack Horseman is most concerned with its main character's development—perhaps the one quality that sets it apart the most from its peers. It also doesn't hurt that BoJack's character flaws—sensitively portrayed by the writers, and masterfully expressed in Arnett's performance—make him far more relatable than a talking, alcoholic cartoon horse has any right to be.

It's a master class in tonal control

If you're worried that a show that's so silly on the surface yet dares to tackle such weighty themes would suffer from severe tonal whiplash, you're right...or you would be if we were talking about literally any other show. But BoJack avoids this pitfall in a number of clever ways, not the least of which is balancing out the darker, more troubled characters with an equal number of upbeat, positive ones. Also, perhaps no other show on television demonstrates such a complete understanding of pacing—specifically, how tightly controlled pacing can sidestep what might otherwise be serious tonal issues.

For example, the penultimate episode of season 2 (minor spoiler) contains perhaps the series' darkest moment, as BoJack is caught by an old friend in a compromising position with her underage daughter. The episode approaches this moment by gradually slowing its rapid-fire pace, incorporating more darkly humorous elements as it does; then, bringing this pace nearly to a halt, more in tune with the pacing of a serious drama. Pacing shifts like this one will always be upended in one of several ways, such as a cut to a different plotline or a well-placed joke, which the writers use to restore a more "appropriate" comedy pacing. This is accomplished so subtly that the viewer is simply left with the impression of a show that somehow manages to be hilarious, gut-wrenching and heartbreaking all at the same time.

It takes big chances, and nails them

BoJack is clearly unafraid to climb out onto some pretty shaky limbs, and it never fails to reward viewers for following. Its bread and butter is in the defying of conventions, and not just through its skillful handing of unexpectedly dark themes and situations. Visually, it's perhaps the most accomplished show of its kind, and nowhere is its convention-defying philosophy more evident than in the fourth episode of season 3, "Fish Out of Water."

In it, BoJack must attend a film premiere at the Pacific Ocean Film Festival, which takes place in a teeming underwater society that was hinted at (in one of those call-forwards) in the season 2 episode "Out to Sea." The vast majority of the episode proceeds with no dialogue—which is arguably the show's strong suit—as BoJack, his head encased in a soundproof bubble, tries to figure out a way to reconcile with director Kelsey Jannings (Bamford), whom he'd gotten fired from his big film project. This conceit, which could have gone terribly wrong, instead results in what might be BoJack's finest episode—an incredibly animated, riotously slapstick, devastatingly poignant half hour that illustrates what a strongly-drawn lead BoJack has become. Such a wild departure is the kind of chance few television series of any kind are willing to take, and it's in taking these chances that BoJack really shines.

It's better at portraying complicated relationships than most dramas

As an extremely character-driven comedy, BoJack gives its characters inner lives that are, shall we say, complicated. "Strongly drawn" never translates to "one-dimensional" here; BoJack and his circle of friends and frenemies are seen to lie, flip-flop, show favoritism and prejudice, and literally go to the ends of the Earth to avoid an unpleasant conversation—just like most of us have, at one time or another.

The fact that relationships are often messy and complicated is one that BoJack understands in a way few comedies attempt to, and that even many dramatic series struggle with. Waksberg has said that one of the show's themes is that actions have consequences, one reason that the writers avoid the "reset" at the beginning of each episode typical of other sitcoms: "A big part of the show is this accumulation of stuff that happens. The D in the Hollywood sign is gone, and now it's gone forever. Sarah Lynn burns BoJack's ottoman, and now the ottoman is burnt. That all cues the audience in that the emotional stuff carries over, too."

This is seen most plainly in BoJack's relationship with ever-upbeat deadbeat roommate Todd, who at the end of season 2 deserts his friend to join a cruise ship improv troupe that may or may not be a cult (because it's still a comedy). Todd's decision is the result of two seasons' worth of betrayals large and small, but he's convinced to return by a simple statement from BoJack that comes close to summing up his character: "Letting you stay with me was the best thing I ever did on purpose. I don't know if I ever told you that. But I should have."

It's the most accurate portrait of depression on TV

The strength of BoJack as a character is that despite his many faults, we can all identify with him in some way—but the strength of BoJack Horseman as a series may be its absolute refusal to label or judge its lead. It's been called a "frighteningly accurate portrayal of clinical depression," yet that word is never uttered on the show. BoJack's tendency to swing wildly between manic activity and gloominess, his way of lashing out even when he doesn't seem to want to, and his deep insecurity all strongly hint at this, however.

We also see, in BoJack's relationship with his mother—both in the present day and in flashbacks—a pretty clear indication of how he got started down this road. After landing his dream role and adopting a brand new upbeat attitude which doesn't quite take, he's brought crashing back down to Earth by his mother, who nails down exactly how he, and most everyone struggling with depression, can often feel: "You come by it honestly, the ugliness inside you. You were born broken... that's your birthright. And now, you can fill your life with projects, and your books and your movies and your little girlfriends, but it won't make you whole."

It's also profoundly optimistic

It's worth reiterating that there's a reason BoJack is such a compulsively watchable comedy despite such serious themes—it's hilarious. For all it has on its mind, it never forgets it's a comedy, and it uses some of the wittiest writing on television to keep things from ever getting too heavy. That BoJack himself never crosses over into being a completely unlikable character despite all of his flaws is a reflection of the series' underlying theme of growth, and the capacity of even the most damaged people (or horse-people) to change.

As Arnett explained, "BoJack... is self-serving to a point that it harms other people. That's what he is grappling with, and it's the first time he's becoming cognizant of it. A real narcissist wouldn't actually recognize that." For better and worse, BoJack's journey is one of self-discovery, and the show's true message is that even if—perhaps especially if—the journey is painful, it's still one worth taking. And you thought it was just a show about talking animals!