Fictional Characters That Were Secretly Autobiographical

Roman à clef literally translates to "novel with a key." Its general meaning is a work of fiction featuring a character who's secretly a stand-in for a real person. There's also a subsection of this where a character is really a stand-in for the author, director, or other artist. Frequently, there are clues that point this out within the work of art itself (hence the "key"); other times, this information doesn't come out until much later. Sometimes the artist confesses this publicly, and other times personal details are revealed posthumously, making it relatively easy to identify.

It's an effective device, because it allows the author to go whole hog on describing an experience entirely from their point of view without worrying about how others might perceive it. Furthermore, it allows the author to smooth over certain facts to make a narrative flow better. It's a common device in all kinds of media, with a recent example coming in the form of Jason Sudeikis revealing that his character in "Ted Lasso" is largely based on himself. Let's take a look at nearly a century's worth of fictional characters that were secretly autobiographical.

Ernest Hemingway introduces the Lost Generation

Ernest Hemingway was one of the most decorated novelists of all time, winning both the Nobel and Pulitzer prizes for literature. In the early 1920s, however, he was still a struggling writer. Trips to Pamplona in Spain to see the running of the bulls, along with a great deal of high-tension drama with friends and lovers, directly inspired his first novel, "The Sun Also Rises." The novel detailed hard-drinking journalist Nick Barnes and his circle of friends, including the disaffected Lady Brett Ashley, her fiance' Mike, and her lover Robert Cohn.

The story followed the tension between Mike and Robert, including a fistfight, as well as the way the entire group was trying to drink away the trauma of World War I; Hemingway referred to this group as "the Lost Generation." Hemingway was in love with the real-life inspiration for Brett, Lady Duff Twysden. He resented Robert's inspiration, Harold Loeb (Hemingway's tennis partner), for having an affair with Duff, and he made him the ostensible villain of the novel. Hemingway engaged in amateur bullfighting just like Nick Barnes and suffered severe injuries to his legs from fighting in WWI, just like his stand-in. The one major difference is that Nick was impotent (and so could never have a relationship with Brett) and Hemingway was not — a bold wrinkle for a macho guy like Hemingway to add to a character that was otherwise like him in every other way.

Sylvia Plath explored her own mental illness in The Bell Jar

Sylvia Plath was best known for her poetry, published in collections like "The Colossus," but she did write a single, immortal novel: "The Bell Jar." Written under the pseudonym of Victoria Lucas so as to spare her mother's feelings, the novel depicts a younger version of Plath taking an internship at a flashy New York magazine. Plath herself attended Smith College and was awarded a guest editorship at "Mademoiselle" in 1953, an experience that wasn't what she had hoped for. In "The Bell Jar," Plath's stand-in was named Esther, and she was similarly haunted by her past and obsessed with the opposite sex.

Despite her success, Esther plunged into a depression spurred in part by feeling oppressed by society's expectations and standards. She wanted to be sexually liberated and not trapped in an oppressive marriage. Living at home again after the internship made everything worse, as her depression made her feel like she was under a bell jar. There was a sense of being trapped and suffocated, as well as seeing the world through a distorted glass. Esther was eventually institutionalized before regaining her mental health. Plath, tragically, took her own life just a month after the publication of "The Bell Jar."

Daniel Clowes is Enid Coleslaw in Ghost World

Cartoonist Daniel Clowes' best-known work is "Ghost World," which was later adapted into a film in altered form by Terry Zwigoff. It's the story of the dissolution of a friendship between two disaffected teenage girls who just graduated from high school. The main character, Enid Coleslaw, is based on Clowes' own experiences, just gender-flipped. Indeed, "Enid Coleslaw" is an anagram of "Daniel Clowes." Clowes said that "she has the same kind of confusion, self-doubts and identity issues that I still have — even though she's 18 and I'm 39!" Clowes is well-known for introducing thinly veiled autobiographical characters in his stories as a way of providing a buffer for his cynical viewpoints, but Enid remains his boldest attempt at this. Her self-hatred and misanthropy was obvious, but the story's focus on the crumbling friendship between her and Rebecca set it apart from his other work.

In the comic, Enid even meets the cartoonist at a book signing, and is repulsed by how weird and pathetic he seems, referring to him as a "perv." The haunted city depicted in "Ghost World" is a combination of Los Angeles and San Francisco, and Clowes moved from the former to the latter.

Bruce Robinson creates the ultimate British slackers

Actor and screenwriter Bruce Robinson created a cult classic with "Withnail and I," which was based on a particularly hard time in his life when he was a poor, aspiring actor. Robinson would go on to write "The Killing Fields" and other classics, but this film has been discovered and rediscovered by new generations of young fans who quote it back to its actors.

Robinson appeared in the Franco Zeffirelli adaptation of "Romeo and Juliet," playing the character of Benvolio. Robinson alleged that Zeffirelli frequently made sexual advances on him, referring to himself as "Bendrovio," and he based the lecherous character of Uncle Monty in "Withnail And I" on Zeffirelli, although the setting was removed to a British countryside vacation. Robinson based Withnail on a couple of people, but it was mostly his actor friend Vivian MacKerrell, who was possessed of a nasty wit and considerable charisma. The film resonates because this is the kind of friendship depicted in a particular moment in time when no one has any money and every moment, lived to its hilt, by its nature has an expiration date. The Robinson stand-in is never named (he's the "I" in the title), though he's referred to as Marwood in the film's credits. By the end of the film, the friendship falls apart, symbolized by Marwood's willingness to cut his hair to get a part.

Sofia Coppola's confusion seen in Lost In Translation

Sofia Coppola's breakthrough 2003 film "Lost In Translation" starred a young Scarlett Johansson as a lonely young woman named Charlotte living a transient existence in Tokyo. While whiling away the hours as her photographer husband is working, she meets a jaded movie star played by Bill Murray, and they strike up a platonic romance. Charlotte is based on Coppola's own experiences spending time in Japan while her ex-husband, director Spike Jonze, was busy working on various projects. Coppola grew up in a privileged, dreamlike setting thanks to being the daughter of famous director Francis Ford Coppola, but "Lost In Translation" reflects how even privilege and wealth doesn't guarantee meaning or purpose.

Charlotte's crisis mirrored Coppola's own, and included platonic relationships with older men. It was widely speculated that the ditzy actress played by Anna Faris was modeled on Cameron Diaz (to whom Jonze was linked during the filming of "Being John Malkovich"), although Coppola said it was based on a composite of people. Tokyo itself was important to Coppola, and she made sure to capture its dreamy, nighttime essence in the form of karaoke bars and neon lights.

Cameron Crowe: Boy reporter

Cameron Crowe spent his teen years on the road, writing stories about bands like Led Zeppelin, Yes, and the Allman Brothers for "Rolling Stone." Later, he became a screenwriter and director, with films such as "Fast Times At Ridgemont High," "Say Anything...," and the box-office smash "Jerry Maguire." That success allowed him to write and direct the labor of love "Almost Famous."

The movie fictionalized his years on the road, as his alter ego was named William Miller (played by Patrick Fugit). The band Miller follows after getting a gig from "Rolling Stone" was named Stillwater, and it's a composite of several bands, including up-and-comers Poco. The scene when Russell, the charismatic guitar player of Stillwater, jumps off the roof of a house into a swimming pool was based on a similar incident involving Duane Allman. Even the overprotective mom and estranged sister were based on elements of Crowe's life. Crowe even had to tell his mother not to bother Frances McDormand, who played William's mom in the film, too much on the set.

Bob Fosse dramatizes his near-death experience in All That Jazz

In 1975, Bob Fosse was editing "Lenny," a film he had just directed about the life of stand-up comic Lenny Bruce. Unhappy with star Dustin Hoffman's performance, he was trying to salvage it in the editing room. At the same time, he was trying to stage a production of "Chicago," for which he co-wrote the book. He was giving the latter his all for his wife Gwen Verdon, with whom he had a rocky relationship. Given his family's history of heart troubles, it was inevitable that he would suffer a heart attack. (Fosse recovered, scandalizing the hospital with multiple lovers coming to visit him, often at the same time.)

Fosse turned that into the 1979 film "All That Jazz," starring Roy Scheider as Fosse's stand-in character, Joe Gideon. In the movie, Gideon is editing a film called "The Stand-Up" while staging a play called "NY/LA." Gideon is a womanizer with a wife and a girlfriend and lives life to excess all the time. He also has a heart attack from all the stress in his life — although his story ends differently.

Federico Fellini attacks writer's block in 8 1/2

Italian director Federico Fellini was already considered to be a genius after directing such classics as "La Strada" and "La Dolce Vita." Having trouble coming up with a follow-up to the latter film, he made a film that was about a famous director who was struggling to make his next film. This metafictional trope is fairly commonplace now, but it was revolutionary when he did it in 1963 with "8 1/2."

In the film, director Guido Anselmi has been tasked to direct a science-fiction film, but he develops "director's block." His personal problems and mental issues get in the way of his even being interested in the movie. At one point, he hires a critic to help him with his ideas, but the critic tears them all to shreds. As Fellini introduces images from his childhood like his beloved family home, magical words that fulfill fantasies, dancing on the beach, and being punished by his Catholic school, the critic rips into them for being too sentimental. These are all Fellini's own memories, which he at once embraces and critiques in the course of the film. Fellini invented an entire catalog of tropes with which the concept of creativity could be examined, and allowed future creators to get as personal as they needed to be.

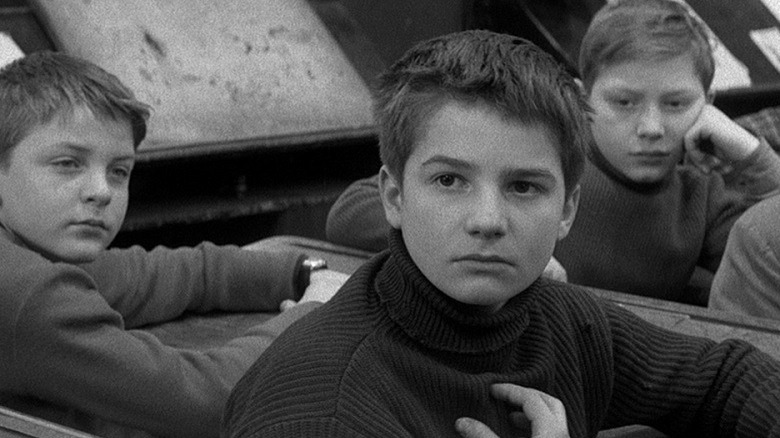

Francois Truffaut kicks off the New Wave with The 400 Blows

Francois Truffaut is the rare example of a film critic who put his money where is mouth was and created his own form of cinema. His first film, "The 400 Blows," is considered to be one of the greatest of all time — it launched the French New Wave. He dismantled the more regimented style of filmmaking that had become standard and made every aspect of it personal, coining the word auteur in the process.

The film was based on his own hardscrabble early life. Born into a poor family and rebelling against authority like the film's protagonist, Antoine Doinel, Truffaut committed petty crimes, skipped school, and was frequently targeted by his teachers for punishment. Doinel is sent to reform school after spending a night in jail, but in the end, he escapes and frolics in the ocean. New Wave films were often marked by a lack of typical three-act structure or plot development, instead focusing on a character's emotional narrative. Many of Truffaut's future films would also be autobiographical in nature, even if he was reluctant to go into details, but "The 400 Blows" remains his best-known movie. For him, the autobiographical details were less important than the feelings he explored.

Carrie Fisher gets frank about rehab

Carrie Fisher's book (and its subsequent film adaptation) "Postcards from the Edge" was clearly drawn from her own life experiences. It's about an actor who grows up in the shadow of her much more famous mother, and her subsequent issues with mental illness, men, and substance abuse. While all of these details are on public record, Fisher insisted that the film was a work of fiction and bristled at the idea that some considered it to be a memoir.

As the years have passed since the film was released in 1990 and Fisher returned to the "Star Wars" franchise, the sensationalistic details surrounding her own life have faded. As such, the assumptions made about the relationship between Fisher and her mother are not as much in the public eye as they once were, giving the film that sense of plausible deniability that she wanted when she fictionalized it. However, she made an important distinction between characters based on real people and actual memoir, explaining, "I wrote about a mother actress and a daughter actress. I'm not shocked that people think it's about me and my mother. It's easier for them to think I have no imagination for language, just a tape recorder with endless batteries." Her stand-in, actress Suzanne Vale, is more a parallel world version of Fisher than Fisher herself, especially with regard to her toxic relationship with her mom.

Harper Lee drew on her childhood for To Kill AaMockingbird

Harper Lee wrote one great novel, 1960's "To Kill a Mockingbird." It's another classic case of a work of fiction drawing heavily on personal details while altering others to create a more fluid narrative. Like her stand-in, Scout Finch, Lee was a tomboy who loved reading. Her best friend, Dill, was based heavily on author Truman Capote. Capote noted in the book "The Worlds of Truman Capote" that the mysterious Boo Radley character that both fascinated and frightened the children was based on an actual man who used to leave them gifts in a tree.

Lee's father was also an attorney who defended two Black men accused of murder who were convicted in 1919. Lee made him into the heroic lawyer Atticus Finch, who set out to defy lynch mobs and seek true justice regardless of race. There were any number of trials that Lee likely drew from for inspiration, from the Scottsboro Boys trial of 1931 to the lynching of Emmitt Till in 1955. Beyond the trial, the fictional setting of Maycomb, Alabama — crucial to the novel's complexity regarding how a place can be good and evil in unexpected ways — was based on Lee's own hometown of Monroe, Alabama.

Jack Kerouac goes On the Road

Jack Kerouac coined the phrase "Beat generation" to mean a number of different things: beaten down, exhausted, or on a musical beat. The 1957 publication of his "On the Road" heralded the popular consciousness of the Beat movement in opposition to the conformity of the era. It was based on a series of road trips he took with his friend Neil Cassady, crisscrossing the country and winding up in places like New York, San Francisco, Denver, and Mexico.

Kerouac's stand-in was Sal Paradise and Cassady's was Dean Moriarty. Together, they searched for the elusive "IT" of meaning as they traveled across America, listening to bebop jazz, drinking, and carousing. The novel was written in just three weeks on a looped piece of paper as a single paragraph, and it has the energy of a particularly enthusiastic letter. Kerouac was inspired by stream of consciousness writing, Cassady's letters, and the work of William S. Burroughs, and that enthusiasm is what transforms the novel's seedier elements into something more intimate, as it's really about the ups and downs of two friends. While Moriarty is a wild man that Paradise admires, he also has burden and commitments that Paradise can't understand. The sense of alienation explored in the novel was deeply influential, especially for the '60s counterculture.

Tennessee Williams and his family's pain in The Glass Menagerie

In his later years, Tennessee Williams admitted that he based his early plays on his family, and his mother and sister in particular. "The Glass Menagerie" is considered to be the most blatantly autobiographical of his plays. The narrator, Tom, even shares Williams' actual first name. Of course, even in the play itself, Tom is quick to warn the audience that the truth of this story is from his memory, and isn't necessarily exactly what happened.

Tom lives with his fragile younger sister Laura (based on Williams' sister Rose) and his mother, an aging Southern belle living in St. Louis. Tom is mostly an observer in the play, going along with his mother's desires to fix Laura up with a husband, or as she puts it, a "gentleman caller." Tom brings over a friend from work who shares an intimate moment with Laura before telling her that he was engaged. Her plans ruined, Tom's mother is furious at him. He reveals to the audience that he left home shortly thereafter, which is actually what happened. The portrayal of a family too toxic and broken to function remains powerful to this day.