Rules Filmmakers Have To Follow When Making A Scary Movie

No other genre of filmmaking can affect audiences in quite the same visceral manner as horror. A good horror movie fills you with an immediate feeling of fear and dread, even while you try to convince yourself that what you are seeing is fictional. Of course, this feeling is not easy to achieve.

That is why the number of genuinely scary horror movies is far outweighed by mediocre, downright terrible fare. Making a good horror movie requires far more than dressing up an actor in scary makeup and pointing the camera at them. In fact, the tone of horror is so difficult to strike that even the best horror franchises are often unable to keep up the quality of the series beyond the first one.

It further complicates matters that the definition of horror changes over time. What was once considered terrifying eventually becomes passé. Due to the audience's fickle nature and unwillingness to be scared by gimmicks they've witnessed in multiple films, smart filmmakers have to adapt their style of horror storytelling to keep up. In today's age, there are certain rules that filmmakers reliably follow in order to bring the scares. Here are 14 of those rules that help create a good horror movie.

Moving away from jumpscares

For the longest time, the "jumpscare" was seen as the calling card of the entire genre of horror filmmaking. The premise is simple. A seemingly peaceful scene is interrupted by the sudden appearance of danger, in the form of a scary ghost, a demon, or a madman, accompanied by a blaring piece of music to underline the dramatic shift in the mood of the scene.

For instance, how many times has Jason Voorhees popped up just behind a victim, despite being a huge, lumbering killing machine? Or how many times has an unsuspecting protagonist opened a bathroom mirror cabinet to take out medicine, and closed it again to see a ghost reflected in the mirror? The jumpscare has been used so often in so many movies (and not just horror) that it has truly become a cliché at this point.

The concept of the jumpscare has also been roundly mocked and satirized on the internet, like in an excellent 2013 "SNL" skit. The audience has become so trained in the art of spotting an oncoming jumpscare that it no longer frightens them. Now filmmakers are learning to move away from the jumpscare, or playing with the trope itself by showing a scene where a jumpscare is expected, but removing the monster from the scene.

Practical vs. CGI effects

For the longest time, it was generally agreed that computer-generated effects had no place in horror films. Since the genre plays out on an intimate scale with many close-ups, it is much easier for audiences to see when something is not really there but is computer-generated. Practical special effects impart a weight and realism to the horror scenes that are much more effective. Plus, the genre has a long, proud history of effects and makeup artists like Rick Baker ("An American Werewolf in London"), Stan Winston ("Aliens"), Tom Savini ("Dawn of the Dead") and many more.

But still, there is only so much you can do with practical effects. As horror filmmakers have grown more ambitious, and the state of CGI has improved, we are seeing more and more horror films make use of the technology effectively. The trick is to use the CGI for smaller details rather than big monsters. "Midsommar" made particularly effective use of small-scale CGI to bring the horror, like the scene where grass appears to grow on a character's hand.

Since humans are trained to notice when someone is a real human or not, CGI works best when it is used to show non-human horrors. For instance, the human form of Pennywise the Dancing Clown in "IT" was played by Bill Skarsgård, but the alien form of Pennywise with huge teeth and many legs was created using CGI.

Keep the monster a mystery

One of the truest axioms in horror filmmaking is "people fear what they don't understand." You can give the protagonist and the side characters as much backstory and motivation as you want, but keep the villain/monster shrouded in mystery. Because nothing works better for a villain's twisted backstory than what the audience's frightened brains come up with.

This is a particularly effective trope in "slasher" horror, which usually deals with a killer who takes lives for no understandable reason — much like ... death itself. What makes Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers such terrifying mythical figures is the fact that even after all these years, we still don't know why they kill. For years, Jason and Michael have been cutting down every person in their path seemingly at random, and that scares us because the danger you do not understand is a danger that cannot be reasoned with, neutralized, or circumvented.

Of course, it is not always possible to keep a villain shrouded in mystery. Often in the third act, the protagonist stumbles across answers regarding the villain's backstory and the why and how of their homicidal nature. This is also the point at which the mystique surrounding the villain lessens as the protagonist prepares to defeat them using the newly-discovered knowledge.

Build the tension

The opposite of the "jumpscare" is the "slow-burn scare." This is much more difficult — and labor intensive — to pull off, and that is why so few filmmakers are able to do it effectively. A slow-burn requires you to build tension throughout the movie, so that the audience is filled with feelings of dread and foreboding as they become more invested in the narrative.

A classic way to do the slow-burn is to show the lead characters starting to lose control of their environment as the story progresses. At first, the characters are happy/carefree as they move into a new house, or visit a cabin for a weekend party, or visit a hotel for a holiday. But then things start going wrong. The environment begins to behave in an unexpected manner and the characters are unable to handle the changes, like a haunted house where objects move on their own, or a lonely cabin with no means of communication with the outside world.

Once the characters are trapped and truly aware of their helplessness, the tension sets in. "The Shining" and, more recently, "Hereditary," are great examples of movies that deliver a slow-burn scare through the careful buildup of tension.

Corruption of Good

There are many theories regarding the mechanics of horror storytelling, and the very nature of the genre itself. At its center, the nature of horror is quite simple. "Horror" is a corruption of what is normally considered "good." When something you know to be good and safe and comforting turns into something dangerous and threatening, that is when you really begin to experience horror.

Consider the evil Nun from the "Conjuring" franchise. The creature is actually a demon called "Valak" that emerged from Hell. Yet for the purpose of striking terror in the hearts of audiences, Valak takes the form of a corrupted "Nun," a symbol of religious piety and righteousness. Similarly, the titular villain from 2013's "Mama" is so terrifying because she is the murderous, ghostly form of a mother who wants to lure children into her eternal embrace.

Sometimes the corruption is not of a human archetype but an entire environment, like a new house a family moves into. The idea that the house goes from being a welcoming abode to a sinister den of otherworldly menace can be a terrifying thing to contemplate. The horror in "The Shining" comes not from a monster or ghost, but from the hotel itself conspiring to end the lives of Jack and his entire family by driving him into a mad rampage.

The rules of the game

Most traditional horror stories are a sort of twisted game that the audience plays through the decisions of the lead characters. The characters are placed in a dangerous environment, and they are pitted against a supernatural villain. But the characters also have a chance at defeating the villain and escaping with their lives if they are able to play the game well.

For that last part to work, the game needs to have an established set of rules, or "lore" behind the horror facing the characters. For instance, the murderous ghost of Samara from 2002's "The Ring" waits 7 days before taking the life of a person that watches her videotape. Those 7 days allow the protagonist time to investigate Samara's origins and think of a way to defeat her. The "Saw" movies are another excellent example of horror movies that set out rules, then make the audience play along — if the characters act as they would, the conceit works; if the characters act in dumb, unrealistic ways, it falls apart.

Similarly the Cenobites from the "Hellraiser" series are all-powerful demons, but they are bound by the rules of the "Lament Configuration" that human characters use to interact with them. Without a set of rules, human characters would have little chance of surviving the first act of a horror movie. On the other hand, an interesting set of rules can keep the tension going as audiences wait to see if the protagonists can game the system to win the day.

Make the horror relatable

There are two sides to horror moviemaking. One is the "spectacle," which is the aspect of the movie that deals with what you see onscreen, whether it is a scary-looking demon or a terrifying ghost. But the spectacle can only work on a deeper level when it connects to something relatable in real life.

For instance one of the most popular theories in film circles is that "slasher" movies are a metaphor for death itself. Here a mute, inescapable killer like Jason Voorhees represents the Grim Reaper, who cannot be reasoned or argued with, and who inevitably comes to take your life no matter how much you try to escape. Similarly, movies like "The Exorcist," "The Babadook," and "The Conjuring" are about losing your loved ones due to your own mistakes or due to circumstances beyond your control.

This aspect of the genre is of particular use in "psychological horror," which is not so much about what you see onscreen but rather what you feel from watching the events of the story unfold. The idea is to ground the horror that audiences feel in something real, which cannot be so easily brushed aside by saying the whole thing is fiction. It's the type of horror that stays at the back of your mind long after the movie ends.

Stick to confined spaces

Horror films rely on a sense of immediate danger. And an immediate danger needs to be accompanied by a feeling that you are pinned in and unable to escape. It would be pretty pointless to make a movie about a guy being chased by a chainsaw-wielding maniac if the guy has access to a high-speed car. Or imagine being attacked by a slow-moving zombie in the middle of a giant football field.

The need for immediate and inescapable danger is why so many horror movies take place inside houses or other confined spaces. The idea is to make the audience feel trapped in the same situation as the lead characters from which they are unable to escape. Sometimes the confined space is more abstract. Like Freddy Krueger being harmless during the day, but being able to murder you in your dreams.

The bottom line is that the characters in the movie should feel like they are trapped in a situation from which there is no escape other than by confronting the monster. This sets up the final act of the movie, in which the surviving characters have no choice but to stand their ground and fight for their lives.

Hint at a bigger world

These days, movies are all about setting up their own cinematic universe. Horror movies are no exception. Slasher franchises were a thing long before Marvel began making movies — just take a look at the 12 Jason Vorhees movies, 11 "Halloween" films, 8 "Child's Play" and "Leprechaun," movies. Even "more serious" horror like the "Evil Dead" and "Conjuring" films prove the scares don't have to end with a single movie.

What makes franchises particularly effective for the horror genre is that they allow the filmmaker to hint at the existence of a larger, even more sinister world beyond the present movie. For instance, Pinhead is a great villain of the "Hellraiser" series, but it is revealed over multiple films that he is only one of many demons that reside in Hell, and there are even bigger threats looming over humanity, of which audiences have only caught glimpses.

Even if you do not intend to start a franchise, hinting at larger forces at work helps increase the evil aspects of a horror villain. "The Shining" has a pretty tragic villain in Jack. But Jack's descent into madness is but a tiny fraction of the true evil that resides within the Overlook Hotel, which drove Jack insane, and that evil hangs like a miasma over the entire film's narrative.

Use unreliable narrators

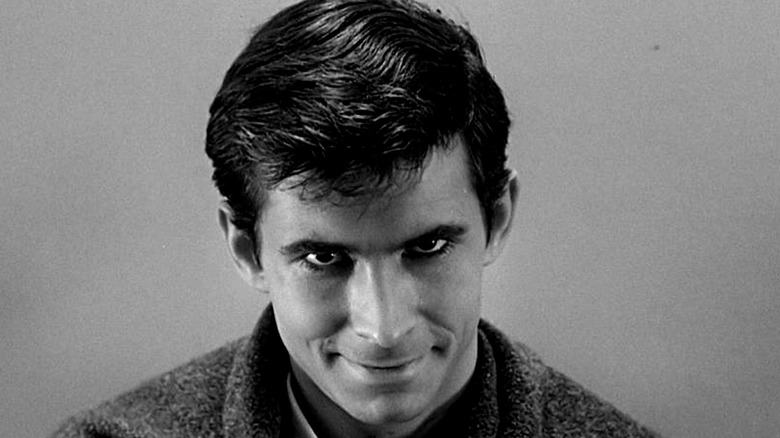

An unreliable narrator is a character in a horror movie who either by accident or design does not reveal the whole truth of the matter to the protagonist, and by extension the audience. For instance, Norman Bates from "Psycho" is an unreliable narrator, and the entire central suspense of the movie depends on what he is not telling the other characters about himself and his mother.

An unreliable narrator doesn't necessarily have to be a bad guy. But their purpose is to sow confusion and fear by revealing half-truths and lies. This allows for a horror movie to set up a big surprise for the audience by showing something that goes against what the unreliable narrator told them earlier. "The Sixth Sense" has Bruce Willis' character as an unreliable narrator whose ignorance of his own true nature leads to the biggest surprise of the movie, one that still gets talked about today.

Of course, care must be taken to not let the unreliable narrator take over the whole story, or the audience will not have anything real in the story to hold on to and get invested in. Like the villain's full motivations, unreliable narrators should be included sparingly and with great restraint in the story.

Morally grey characters

Characters in horror movies come in for a great deal of punishment at the hands of the film's monster. As such, it is useful to make the characters morally ambiguous rather than out-and-out heroes, since this makes it easier for the audience to see them suffer all kinds of horror as a sort of karmic retribution.

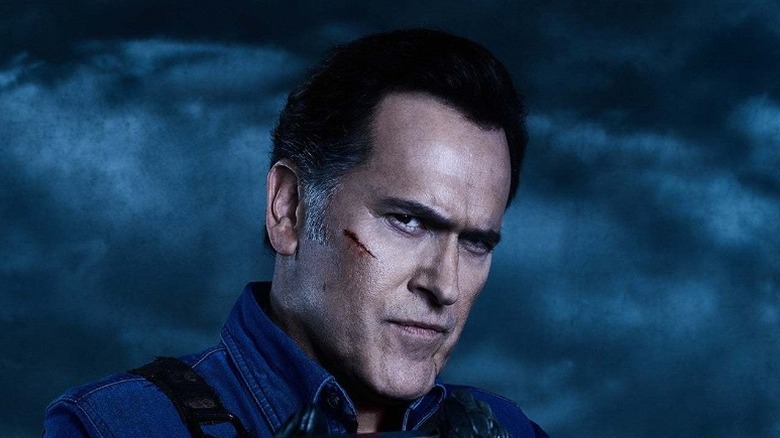

The "Hellraiser" series is particularly notorious for picking such terrible people as lead characters that you actually feel happy watching them get disemboweled by Pinhead and his crew. Similarly, slasher films used to frequently depict hard-partying, fornicating teens getting brutally murdered by the killer for the perceived sins of gluttony and lust. Even Ash Williams (Bruce Campbell) from "Evil Dead," possibly the most heroic horror movie character, is far from a saint and has done his share of messed-up things.

In general, horror stories are morality plays, and such plays need characters that have shades of grey in them. Those shades are then contrasted against "true evil," as personified by the movie's central monster, to remind audiences of humanity's insignificant place in the greater order of the chaotic world.

A legit chance at beating the monster

A movie where the characters are unceremoniously killed off by the monster would get boring very fast. That is why it is necessary to show the heroes as having a fighting chance at defeating the monster, no matter how faint that chance might be.

For instance, Freddy Krueger's victims are able to fight him by taking control of their dreams. Pennywise's victims are able to get over their fear of him and reduce the maniacal clown to a literal puddle of goo by calling him names. Even the Hellpriest Pinhead needs to play by the rules of the Lament Configuration instead of wreaking havoc however he pleases.

Usually any victory over the monster is only temporary, or the monster moves on to inflicting pain on a fresh set of victims. But it is important to stick to the rules that you set for dealing with the monster, or later films in the series can turn franchise lore into a muddled mess that requires a fresh reboot.

Make the camera a player

Perhaps no other genre requires active use of the camera as part of a scene as much as horror. That is because horror requires the audience to sometimes be unaware of its surroundings, living vicariously through reveals meant to simulate your eyes discovering that scary thing in the darkness.

For instance, so many horror movies show a closeup of characters staring in horror at something in their room, only to then suddenly pan the camera to the other side of the room to reveal a demon/witch standing before them. This kind of technique only works if the camera acts like a participatory member of the cast that reacts to the horror at the same time as them. Also consider the use of things like the "Evil-Cam" POV in Sam Raimi's "Evil Dead" movies, a shot that puts the audience on edge and gives you a peek from the evildoer's point of view.

Of course, the most inventive use of camera angles is seen in "found-footage" horror films like "The Blair Witch Project." That film never showed us a glimpse of the actual witch, but it still gave audiences nightmares based on what showed up on-camera, and what was hinted to be lurking nearby just off-camera.

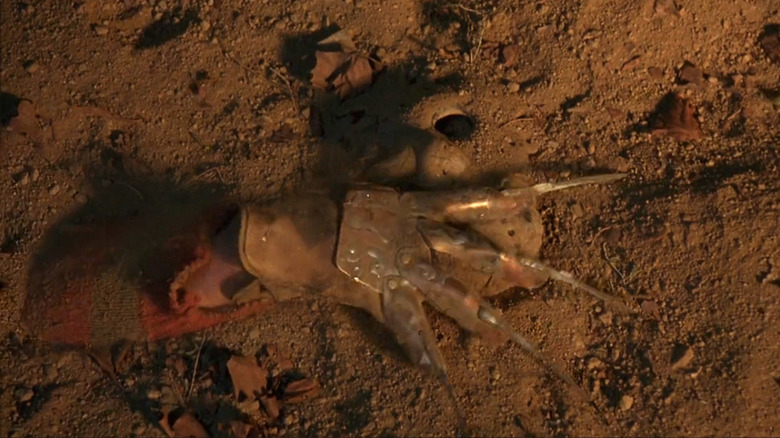

Leave a hook at the end

Crowd-pleasing horror movies needs to show the good guys winning over the evil entity of the film, no matter how high the odds were stacked against such a victory. But just because the characters have won the battle does not mean they have won the war — which you show by adding a hook at the very end of the movie.

For instance, how many times has Pinhead been banished from the realm of mortals, only for the cube that summons him to end up in the hands of some new character? Slasher movies are notorious for having a hook at the end that indicates the killer is still alive and kicking. Even the "Conjuring" series has a recurring villain in the form of Valak. Another classic example of this trope is the surprise ending of 1993's "Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday," in which the unmistakable arm of Freddy Krueger emerges from the ground and grabs Jason's signature match, setting up a storyline that would be paid off a decade later in the 2003 monster-movie-mashup "Freddy vs Jason."

What makes this sort of a hook particularly effective in horror movies is that it plays into the idea that the evil shown in the story is beyond human understanding, and can never truly be wiped out. No matter how hard you try, no matter how much you sacrifice, like a sliced-off head of a Hydra, the evil will grow back into a new form to terrorize humanity anew. Because ultimately, is there anything more terrifying than the idea of a monster that can never be destroyed?