Questionable Things We Ignore In The Toy Story Franchise

The "Toy Story" franchise is one of the most beloved movie series of all time. Starting with 1995's groundbreaking "Toy Story" and continuing through a series of touching, heartfelt films that concluded — at least for now — 24 years later with "Toy Story 4" in 2019, these computer-animated classics about toys that are secretly alive have become a cultural touchstone. Not only do the original adventures of vintage cowboy doll Woody, space ranger action figure Buzz Lightyear, and the rest of the toys still hold up decades later, but each subsequent film deepens these characters' stories, further endearing them to audiences of all ages.

As successful and revered as the franchise is, though, close scrutiny reveals there are plenty of things about the series that viewers can poke holes in, from faulty logic to head-scratching plot points and uncertainties about who the "Toy Story" films are really made for. We may have a friend in Woody, Buzz and the gang, but that doesn't mean their films always make sense. Here's our list of questionable things we ignore in the "Toy Story" franchise.

How has no one discovered that toys are alive?

The "Toy Story" franchise establishes a fantastical world where any child's plaything with a face is alive. The toys don't let the kids that love them or their families in on their secret, and Woody even indicates that there are rules that prohibit toys from revealing that they're living, thinking beings. While Woody deliberately breaks this rule in the first "Toy Story," for the most part, the toys keep the secret. However, they do it in such a half-hearted, unconvincing way, it's impossible to believe no one's noticed their true status.

Throughout the series, there are multiple times when people might discover toys are conscious. For example, in "Toy Story 2," when Buzz and several other toys go searching for a missing Woody, they hide inside traffic cones to disguise themselves while crossing a busy street, causing multiple accidents and all kinds of mayhem in the process. In "Toy Story 4," Bo-Peep has become a lost toy who engages in lots of derring do out in the open. Even if people mostly ignore toys or turn a blind eye to what they can't understand, it defies logic that no one's ever realized something strange is going on — especially if you multiply the antics of Woody and his pals by the billions of toys engaging in similar behavior around the world.

Woody often isn't a great leader — or a great guy

With the voice of Tom Hanks and the look of a sheriff straight out of the Old West, Woody has a warm, reassuring quality that makes it easy to see the good in him. But over and over again throughout the "Toy Story" franchise, Woody has demonstrated he can be jealous, insecure, selfish, and controlling, resulting in problems for the toys who look up to him as their leader. This is most apparent in the first movie when Andy gets Buzz as a birthday gift. Woody has always been Andy's favorite toy, but when he sees how cool and modern Buzz is, he quickly lets his jealousy get the better of him, and in an attempt to ensure Andy will pick him over Buzz to take on an outing to Pizza Planet, he accidentally sends Buzz out the window.

While Woody manages to overcome his insecurities and befriend Buzz, it's apparent he's still deeply flawed in the fourth film, when he puts his loyalty to his new owner Bonnie above everything else. Although his devotion is well-meaning, his desire to get Forky back from an antique store puts Bo-Beep and his other toy allies in grave danger. Even after they barely escape with their lives, he wants to try again despite their protests. Woody's inability to balance the needs of his followers with his goals makes him a terrible leader and an even worse friend.

The rules around toys dying are unclear

The issue of toys dying — or being murdered — is brought up quite a bit in the "Toy Story" franchise, but what would actually cause a toy to die is unclear. Throughout the four movies, the only time the toys face such catastrophic bodily harm that death is clearly imminent is during "Toy Story 3" when they get trapped in a trash incinerator and almost fall into the fire. Other injuries seem to have much less of an impact on them, even though the toys often seem horrified by the possibility of physical harm.

In the original "Toy Story," Potato Head accuses Woody of murder when he accidentally sends Buzz out the window, but Buzz is far from dead — or even hurt — by the fall. And even though toys have undergone all kinds of terrible ordeals in each of the movies in the series, from torture at the hands of children to de-stuffing and the threat of being run over, none of it has ever really kept a toy down. So the toys may talk about dying, and audiences may accept that it's possible, but there doesn't seem to be a whole lot that can actually take a toy out. Does that mean the "Toy Story" films simply mention the possibility of death to increase the drama? The franchise hasn't made that clear.

Why don't Buzz Lightyear toys know they're toys?

Most toys seem to know they're toys right out of the box. Somehow they understand their role in a child's life and the rules around pretending to be inanimate. Although they sometimes take on traits of the kinds of toys they are — for example, each Barbie seems to have a special devotion to her particular vocation and Rex, the timid T-Rex, still aspires to be ferocious — they ultimately know they're vehicles for a child's imagination.

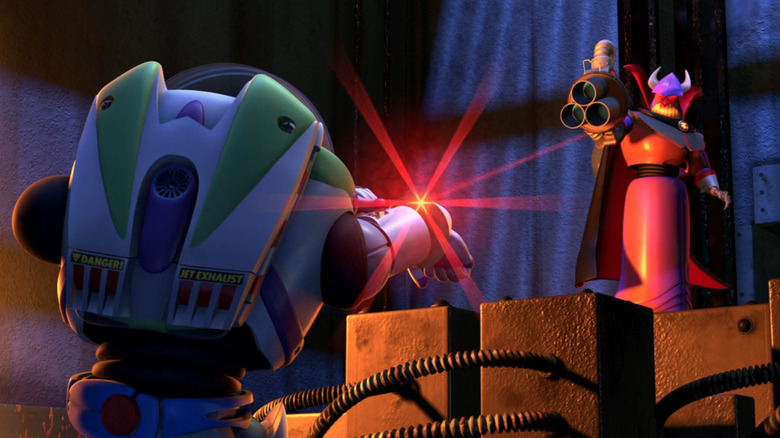

That's part of what makes Buzz's belief that he's a real space ranger so amusing in the first "Toy Story" installment, even if it doesn't make much sense. Buzz follows space ranger protocols and talks like he's on the intergalactic mission that makes up his toy line's backstory. He even believes he can fly. Fortunately, Buzz bounces back from his identity crisis quickly, but in "Toy Story 2," it becomes clear that all the toys in the Buzz Lightyear line believe the same thing Buzz originally did, including the action figure of the evil Emperor Zerg who escapes a toy store to go after Buzz. But why do only the Buzz Lightyear dolls seem to have this particular glitch? A flaw at the factory? Wires crossed when they were somehow infused with life? A convenient plot point? We'll never know for sure.

In the first movie, Woody scars a child for life

While the toy characters of "Toy Story" easily won over audiences, there was one character who didn't fare as well: Sid, the child who lived next door to Andy. Sid was notorious for the sadistic way he treated his toys. And after seeing how he pulled apart toys and recombined the parts to create something new, plus his use of fire to burn them and rockets to launch them into the stratosphere, some viewers labeled Sid a psychopath.

So audiences were on Woody's side when, after he and Buzz fell into Sid's clutches, Woody enlisted Sid's toys to scare him into treating them better. Woody had Sid's toys reveal they're alive and surround Sid as Woody told him to "play nice." Needless to say, Sid was terrified and probably scarred for life by the incident. However, while Woody may have gotten Sid to treat his toys better, many ignore the fact that Sid didn't really deserve what he got. After all, Sid didn't know toys were alive, so from his perspective, he wasn't hurting anyone with his rough play. If anything, he was expressing his creativity by designing new toys out of the ones he already had. Sid may not have been kind to his toys — and his parents' lack of supervision seems like a problem — but given what he knew about toys based on the rules the toys themselves followed, Sid wasn't nearly as bad as he seemed.

Forky's suicide attempts are played for laughs

"Toy Story 4" introduces the character of Forky, a discarded spork that Bonnie turned into a toy to comfort herself when she was scared and alone on her first day of kindergarten. Forky, however, was less than thrilled to discover he'd been reimagined as a toy instead of the trash he saw himself as. So when Bonnie took him home, Forky did everything in his power to return to a garbage can. Knowing how attached Bonnie was to Forky, Woody took it upon himself to ensure that Forky fulfilled his destiny as a toy, a scenario that sees Woody repeatedly doing everything he can to prevent Forky from literally throwing himself away.

Forky's desire for the sweet release of trash can be seen as a metaphor for suicide, and that makes the character's numerous attempts to stop his life as a toy and seek oblivion in garbage vastly more disturbing. And yet that's easy to overlook, since Forky's desire to end his life is presented as an amusing quirk that Woody has to fight against. While Woody eventually convinces Forky that life as a toy is worth living, the fact that Forky's belief that his usefulness has ended and he should be tossed away sheds a much harsher light on his plight.

There's a lot of sexual innuendo for a kids' movie series

From the opening of the original film, it's clear that despite being touted as a movie for kids and families, "Toy Story" won't shy away from sexual innuendo. As Woody gathers the toys for a meeting, he's approached by Bo-Peep, who suggestively tells him she can get someone else to watch her sheep so the pair can spend some time alone, leaving Woody so enamored, he's a sputtering mess. The movie also sees Mr. Potato Head hoping Andy is gifted a Mrs. Potato Head for his birthday and Woody ending the film covered in lipstick kisses doled out by Bo-Peep following his and Buzz's safe return to Andy's room. While none of this is explicit, the meaning behind it is clear, and the tradition continues in subsequent films.

Take "Toy Story 3." Buzz, who has had a crush on Jessie since the second film, suddenly becomes a lot more forward when he's switched to Spanish mode, a change Jessie clearly appreciates — and wants to revisit even after Buzz is reset to his English-speaking self. Then there's Barbie and Ken, whose instant attraction is marked by Barbie declaring she likes Ken's "as... cot," a compliment that's directed at his derriere, not his clothing. That's a lot of sexual overtone for a series about supposedly innocent toys. Even if it amuses adults and goes above kids' heads, it also may lead to some uncomfortable questions for parents.

The movie judges children (and pets) based on their treatment of toys

"Toy Story" is a series made for kids about kids' playthings. Playing with toys is an experience everyone will recognize no matter how old they are or how they treated their toys. That's part of the franchise's universal appeal. And yet, the movies can be surprisingly harsh in their judgment of kids — and even pets — based on their treatment of toys. The most obvious example is Andy's neighbor Sid and his dog Scud, who are painted as sadistic monsters in the first film. Sid and Scud are contrasted with Andy and his dog, Buster, who are gentler with their toys and use them in pretend play where no one's hurt.

In "Toy Story 3," children's varied treatment of toys is revisited when Andy's toys are donated to Sunnyside Daycare and are manipulated into being kept in the room where the toddlers play. The toddlers are terrible to the toys, sitting on them, using their heads as paintbrushes, gluing glitter and macaroni on them, and all sorts of other rough play. In contrast, the room with the slightly older children is shown to be a paradise with gentle play, hugs, and fun imaginary scenarios. However, toys are made for children, and even though it's understandable that the toys would want to be treated nicely, viewers may forget that toddlers' and even older kids' roughhousing is part of the job.

Toys' limited choices in life are a recipe for disappointment

In "Toy Story 4," Gabby Gabby, a doll who's been rejected because of her defective voice box, observes, "Being there for a child is the most noble thing a toy can do." It's an ethos Woody lives by with Andy and then Bonnie, but the sad reality is that toys don't have many other options in life. While their preference may be to be there for a child, that can only last for a few years before the child outgrows them, resulting in the toy being neglected, put in the attic and forgotten, or donated. Yet this is still better than the alternative: being displayed in a museum, relegated to an antique store, or becoming a lost toy with no purpose to fulfill.

So while "Toy Story" shows charming moments of playtime between Andy and his toys — and later, Bonnie and her toys — the reality is that a majority of toys' lives are depressing and brutal. While toys may have happy moments with a child, and if they're lucky, maybe even two or three, given how long their lives are and their limited options, the moments when they live up to their potential and are able to be there for a child are woefully fleeting. It's a reality that's at the crux of Woody's journey throughout the "Toy Story" films, even though it's one both Woody and audiences prefer not to pay too much attention to.

Most toys are terribly traumatized

Given that toys' best years end when their child hits their tween or teen years, most toys are terribly traumatized by the rejection they suffer. A good example is Jessie in "Toy Story 2," whose positive attitude hides a deep fear of getting placed in the darkness of storage. While she was once the favorite toy of a child named Emily, her interest in Jessie was replaced by an interest in beauty products, and eventually she gave Jessie away, plunging her into a life that was so sad, she welcomed the opportunity to be put on display in a museum even though she wouldn't have anyone to play with there.

Even toys in supporting roles are shown to have similar issues, like Duke Caboom in "Toy Story 4," an action figure based on a Canadian stuntman. Commercials for the toy showed him completing incredible feats, but when Duke's child Rejean learned Duke couldn't really do the stunts as advertised, he discarded him — a rejection Duke was still dwelling on after years in an antique store. The trauma suffered by toys is simply an unfortunate byproduct of their purpose in life, but it's one that's more comfortable to ignore, given that it may make us want to stop giving toys to children.

The plot of all four movies is essentially the same

The original "Toy Story" was a technical and narrative achievement. Yet while characters like Woody and Bo-Peep have evolved over the years, the plot structure of the franchise's films haven't varied all that much. Cue Randy Newman's "You've Got a Friend In Me" and scenes of Andy playing with Woody and the gang and you know you're watching the opening of a "Toy Story" film. After scenes establishing the toys' lives, something thrusts them into an adventure, usually one outside either Andy or Bonnie's rooms, whether it's Woody pushing Buzz out the window, Woody being stolen by the owner of Al's Toy Barn, the toys being donated to a daycare, or Woody and Forky getting lost during a road trip.

Finally, the third act involves some heavy action as the toys race to set things right, which can mean everything from ensuring they get on the moving van to Andy's new home or finally catch up with Bonnie and her family's camper. While it's absolutely true that the "Toy Story" movies are tightly constructed and each have unique touches that differentiate them, at their core, their plots follow the same basic outline. It's something we may even notice, but ultimately doesn't keep us from watching — and loving — these films.

The series resonates more with adults than kids

One of the biggest questions the "Toy Story" series brings up is who the movies are actually made for. While their bright, shiny animation, toy characters, and G ratings make them kids' movies in the eyes of the general public, the filmmakers include deeper themes in each film that only older viewers truly understand. From the inevitably of change to the desire to stay relevant or the challenge of letting go and moving on, the "Toy Story" films can get downright existential. Kids may understand the changes that come with growing up on a general level, but most are in a hurry to get there. On the other hand, many adults look back on their pasts with wistful nostalgia, something that's key to Woody's story across all four films.

That's why it's no surprise that it's often adults, not kids, that are reduced to tears by the movies in the series. So while "Toy Story" and its sequels may be considered kids' films, anyone who's seen one as an adult knows they're much more. Kids might enjoy the films at a young age, but they'll find them even more meaningful if they watch them in young adulthood and beyond.