Things You Forgot Happened In Inception

Is all that we see or seem but a dream within a dream? That's the question Edgar Allan Poe asked almost 200 years ago, which Christopher Nolan takes a step further in "Inception." What if that dream was within another dream ... within another dream ... within another dream? The movie is a standalone blockbuster that still takes up a huge chunk of the cultural consciousness years after its release, without a single sequel or spinoff to keep it in the public eye. You'd have to go all the way back to 1999's "The Matrix" to find a movie that so successfully combines mind-bending concepts with good ol' meat-and-potatoes action.

In "Inception," Nolan takes the well-worn heist formula and turns it into something totally new by moving the action from a bank or museum to the human unconscious. As professional dream-extractor Dominic Cobb says, "Once an idea has taken hold of the brain it's almost impossible to eradicate." "Inception" itself is one of those ideas — but just because it's stuck in all our brains doesn't mean our memory of it is necessarily accurate.

Amid all the movie's twists and turns, there's a lot you might have forgotten about "Inception," if you even caught it in the first place. But those details are worth revisiting, and that's what we're going to do today. These are the details, twists, and revelations you forgot happened in "Inception."

Scenes were rarely dreamlike

The possibilities of a movie that takes place mostly (or, depending on what you think of the ending, entirely) within dreams should be endless. So it shouldn't be surprising that many viewers were disappointed with what they actually got. Most of the settings of "Inception" — a warehouse, a hotel, a bunker — aren't anything you couldn't find in the average action movie. And while the rules "Inception" sets up aren't much less arbitrary than the ones in real dreams, they're much more rigid, to the point of being quasi-mathematical: The body's position in one dream level affects the gravity of the next level, time slows down in predictable intervals the deeper you go, and so on. But viewers who complain about this apparent lack of imagination may have forgotten that there's a concrete narrative reason these dreams seem so undreamlike.

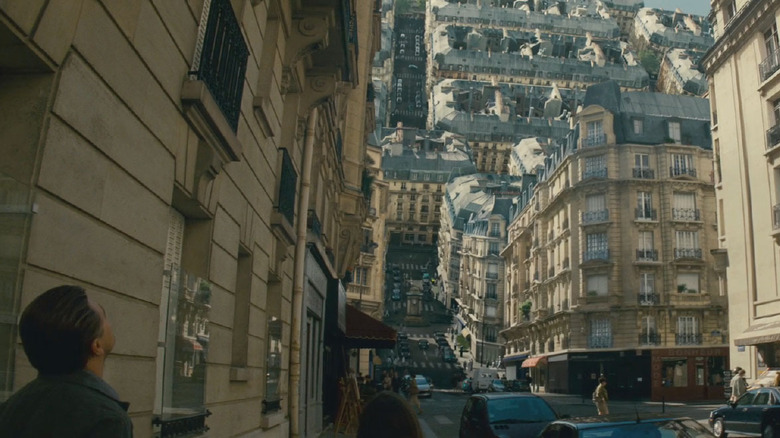

The one time Nolan cuts loose is when Dom's protégé, Ariadne (Elliot Page), tries out dream design for the first time. Surreal imagery, like the city streets that run straight up into the sky, ensues. But Dom soon explains that it's dangerous to have this much fun in a real extraction. Every time the infiltrator uses dream logic to do something impossible, it alerts the victim's unconscious that something's up. That's bad news for the extractor, as Ariadne finds out the hard way when the inhabitants of the dream world swarm her.

The characters all pronounce Saito's name differently

Nolan told Entertainment Weekly he thought of Dom's team as a film crew. That would make Ken Watanabe's character, Saito, the producer: He hires the crew for a project, to convince Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy) to break up his company, and he puts up the money. Like a lot of producers, he gets pretty hands-on with his investment, hanging around the "set" while the crew is working. If Saito really does represent the producer, it must have been cathartic for Nolan to make him regret micromanaging the mission, since he gets shot in the dream and nearly dies in reality.

Watanabe had worked with Nolan before, appearing as the decoy Ra's al Ghul in "Batman Begins." Apparently, the director didn't absorb any of the Japanese star's native language from their relationship, because the pronunciation of Saito's name in "Inception" wanders all over the place. For most of the first half, DiCaprio and other actors pronounce the first syllable like the English word "say." But in the second half, it sounds more like "sigh." (For the record, the second one is correct.) At least "Inception" isn't as inconsistent as the "Avengers" movies, which use apparently every possible pronunciation of "Thanos" at one time or another. Then again, at least those movies have the excuse that his name comes from a dead language.

Most scenes begin in the middle

Twice, Cobb explains a surefire way to tell if you're dreaming: "You never really remember the beginning of a dream, do you? You always wind up right in the middle of what's going on." Of course, movies are that way too. Filmmakers only have a limited amount of time to tell their stories, and they have to fight to keep viewers' attention. They're not going to waste a minute of their precious two-ish hours giving the audience information they can fill in for themselves — that way lies "Birdemic." Thus, you rarely see movie characters walking into houses or out of cars.

If that's true of most movies, it's even truer of "Inception." Once you know to look for it, this detail adds even more uncertainty to the question of whether or not the entire affair is a dream. Nolan introduces Tom Hardy as Eames talking to Cobb in a bar halfway around the world, with no word of how Cobb got there. In the bunker dream, we see an entrance to a secret tunnel, but we never see anyone crawl into it — they just appear inside the tunnel. And in the famous scene of the characters washing up on the shore of limbo, we never actually see them wash up — they're just lying in the water, then on the beach, then walking inland.

Inception plays with you just like the dream does

Even within the fiction of "Inception," it's hard to fathom the amount of effort it would take Dom's team to create an entire world. Yet he tells Ariadne it's simple: "You create the world of the dream, you bring the subject into that dream, and they fill it with their subconscious." Movies are the same. Over 100 years ago, Russian director Lev Kuleshov famously proved that if you see two images juxtaposed, your mind will create connections between them.

Nolan has a lot of fun reminding viewers that they're doing the same thing watching his movie as Dom's marks do with his dreamscapes. We see Dom take Fischer's drink on the plane, and we see him hand it back to him, but we never actually see Dom drug it. In the flashback to Dom's decision to go on the run, we see an unknown figure hand him a plane ticket, and we see Dom holding it, but we never see him take it. We see a lot of characters fall off buildings, or at least we think we do — in reality, we never see any of them land. And of course, a PG-13 movie could never show Dom and Mal (Marion Cotillard) getting crushed by a train, but that doesn't mean you don't remember seeing it.

Fischer accidentally predicts where he'll go next

Dom's plans are already in shambles, but they only get worse when Mal turns up in the third level and abducts Fischer. To get him back, Dom and Ariadne have to go to a level he calls "Limbo," which he and Mal explored years earlier. Since the two of them created it through lucid dreaming and it isn't at risk of waking an exterior target, it's one of the few places "Inception" gets to explore truly dreamlike surrealism. Every house the pair ever lived in sits side by side, with a suburban cottage next to an urban brownstone. Most striking of all is the entrance: It's a beach lined with a massive collection of crumbling buildings.

This scene shouldn't be a surprise if you were paying attention. The very first shot flashes forward to Dom washing up on that beach, and flashbacks throughout show Dom and Mal at work building Limbo. But there's another bit of foreshadowing in the level directly above Limbo. It's a less surreal but still exotic location: An Arctic bunker inspired by the James Bond classic "On Her Majesty's Secret Service." It's fun to watch, but apparently not as much fun to trudge through — Fischer complains, "Couldn't somebody have dreamed up a g**d**** beach?" He gets his wish, even if he gets there a lot more violently than he would have liked.

Dom chooses an ironic theme song

"Inception" doesn't skimp on expensive action and big science fiction ideas, but Nolan still grounds it all in basic human emotions. Dom isn't a happy-go-lucky action hero or a stoic badass, as other movies might have made him. Instead, he's a man haunted by regrets — literally, given the ghostly Mal who follows him through his dreams — over his role in Mal's death and his forced separation from his children. His attempts to make enough money with his unique talents to get home again only pile on more regrets, as disappointed clients send murderous goons after him all around the world.

To wake up from their dream mission, extractors use a "kick," usually represented by a fall. You can get a kick any time in an ordinary dream, but these heists demand precise timing. The team coordinates a kick by playing a song on the dreamer's headphones, which echoes through each layer of the dream. The specific song Dom chooses has a special irony, in light of all the guilt he struggles with: He plays French chanteuse Edith Piaf's classic "Non, Je Regrette Rien," which translates to "No, I don't regret anything." If that's not enough, there's yet another instance of musical irony that almost got cut for being too obvious: At the same time she's playing Mal, Marion Cotillard is also playing Piaf in "La Vie en Rose."

Dom's mission may be more personal than he lets on

"Inception" finds many ways to echo Dom's regrets. To manipulate Fischer, the team has to go after his weaknesses. They find a big one in his strained relationship with his father, Maurice (Pete Postlethwaite), who takes more interest in his work than his son. When the crew starts profiling Robert, his father is dying. Even when Maurice can barely speak, he still finds the strength to tell his son he's disappointed in him. By the time Dom gets to work, Maurice is dead. This is the perfect opening for the team to incept the idea of breaking up the company in Robert's head — his overwhelming sense of grief and conflict can be used to manipulate him with relative ease.

But nothing in "Inception" is there by accident. It's one heck of a coincidence how much Dom's "one last job" connects to his motivation for taking it, huh? Dom is also a father whose work has kept him from his children, though it's against his will instead of by choice. Can he see his own future in Maurice? Is he afraid his own children will resent his distance just as much as Robert resents his father's? If so, his insistence that the simulation needs to give Robert catharsis becomes all the more meaningful — it's a way for Dom to find catharsis for himself.

You get manipulated right along with Fischer

If we look at "Inception" as a metaphor for its own creation, the crew's ends are just as relevant as their means. They're creating fictional worlds and narratives to manipulate their viewers' emotions — in other words, they're making movies. Dom even insists, "Positive emotion trumps negative emotion every time. We all yearn for reconciliation, for catharsis." Translation: The audience wants a happy ending.

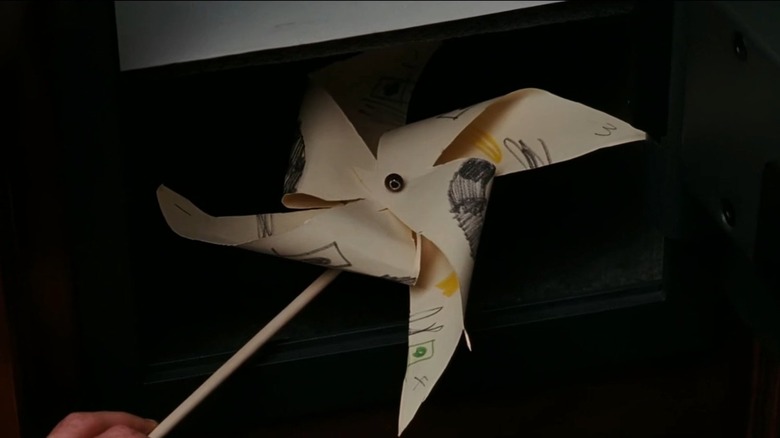

Dom gives one to Fischer when he finally gets him to open the locked room hidden in the Arctic bunker. It's designed to resemble the hospital bed/office where we last saw his father — ergo, a callback. Inside, there's a safe, containing a new will giving Fischer the power to break up the company. More importantly, there's also a pinwheel, which is a remnant of Fischer's one positive memory of his father. It reveals that deep down, his father cherished their relationship just as much as his work.

Written out like that, it's all clearly a transparent con job. But that's not how it appears on film. We know Dom has manipulated Fischer into this emotional breakdown, but Nolan's filmmaking, Murphy's acting, and Hans Zimmer's score all make us feel the catharsis right along with him. It's hard enough to make a viewer feel what you want them to feel. But to flat-out tell them you're taking them for a ride and get them to willingly go along with it anyway? That's art.

That top isn't Cobb's

For all its flashy effects, the most iconic image in "Inception" is also one of the smallest: Dom's top, the "totem" he always carries to check if he's in a dream or reality. If it falls, it's real. If it never stops spinning, it's a dream. It's the centerpiece of the movie's unforgettable ending, which cuts out before we learn the answer.

At least, that's the way you may remember it. In fact, the top isn't Dom's totem at all. When Ariadne presses him to tell the whole story of his traumatic history with Mal, he reveals it's actually hers.

This puts the top's meaning in a whole different light. If it's not Dom's totem, what does he learn by spinning it? Was he able to take it as his own? Is it a reminder of his guilt? Or is he afraid that he's trapped in Mal's dream? No matter what, it shows the dangers of ignoring Arthur's (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) advice. Each totem has something unique about it that only the dreamer can recognize — for instance, Arthur carries a specially weighted die. He warns Ariadne not to let him touch hers — "That would defeat the purpose," because then he'd be able to replicate it. If only Dom and Mal had listened, they might not be in this mess.

An earlier scene spoils the ending

The ending of "Inception" has divided fans since it debuted. It's perfectly designed to do so — after we think we've seen the happy ending, the camera changes focus to that darned top, spinning away. It sounds like it's just about to fall over, but it never does. You can find all kinds of evidence for and against the last scene being "real," at least within the reality of the narrative. Even Nolan refuses to give away the secret, and his few cryptic statements suggest he doesn't think his answer would be definitive anyway.

All these arguments take the same premise for granted: That it's important whether or not Dom is dreaming. You may have forgotten an earlier scene that spells out that this actually doesn't matter at all — at least not to Dom. He tells Ariadne, "I just need to get home. That's all that matters." Everything else is irrelevant, including whether he's really home or not. Even if Dom's trapped in an illusion, as long as he believes in it, he doesn't care. Notice that he leaves the top in another room instead of watching it intently, like he does every other time he uses it. If that's not enough evidence, consider Nolan's other movies. Both "Memento" and "The Dark Knight" end with the heroes discovering a horrible truth and choosing to either believe or convince others to believe in a more reassuring illusion.

The credits are a wake-up call

As we've outlined, "Inception" uses dreams as a metaphor for movies. The dreams have a director (Dom), actors (Eames), and a screenwriter/production designer (Ariadne) who fills a "set" with visuals and narrative for the benefit of a viewer (Fischer). Like a movie, a dream takes place in the dark, until the lights go up and the viewers go back to their waking lives.

That last detail is hammered home in the movie's credits. It's nothing unusual for movies to play a song from the soundtrack over the credits, unless the producers decide to spring for an original jam to try and get in on that "Best Original Song" Oscar action. "Inception" takes the first route by replaying "Non, Je Regrette Rien" as the names roll by. But remember, that song isn't on the soundtrack just to set the mood — It's the kick, reminding the dreamers it's time to end the dream. And isn't that just what the audience is doing when they leave the theater? The dream is over — time to wake up.