We Finally Understand The Ending Of Akira

There has likely been no film more influential for the cyberpunk genre than Katsuhiro Otomo's iconic 1988 science-fiction anime "Akira." Yet, after more than three decades, the film's philosophical finale still has viewers questioning what all of the chaos and destruction means. It's a visually frightening bloodbath with an equally frightening yet relatively open-to-interpretation message.

Set in a post-war futuristic 2019, Neo-Tokyo is a self-imploding city laden with street gangs, terrorist attacks, and violent protests. The government is corrupt and refuses to inform its citizens what is going on, which has led to the formation of resistance groups and fanatical cults. Amidst this, biker gang leader Shōtaro Kaneda's childhood friend Tetsuo Shima is involved in an accident that awakens a troubling power within him. The government realizes that the power Tetsuo has is nearly identical to that of Akira, a telepath who was responsible for the destruction of the original Tokyo in 1988.

It's a race against divine power, government corruption, and of course, the clock as everyone struggles to stop the impending collapse of their city yet again. The action builds to an unforgettable climax, but what does the ending actually mean?

The morality of nuclear weapons and secret operations

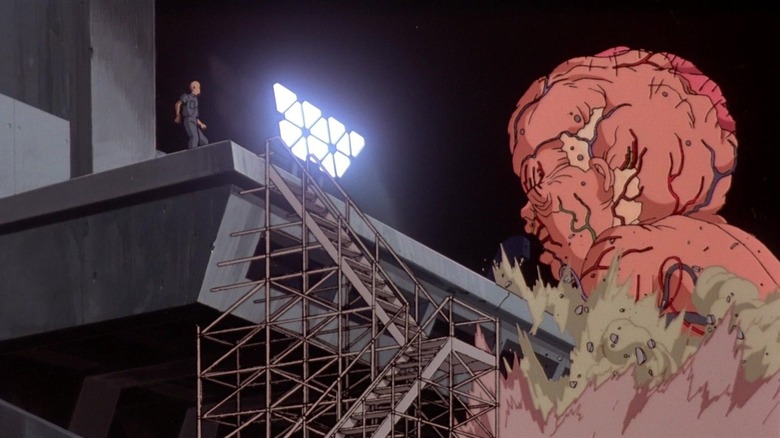

Cautionary tales about political violence don't usually culminate with a grotesque, crawling mass that absorbs an entire city. However, "Akira" uses said all-consuming, flesh-like being as a way to illustrate how becoming too powerful too quickly can be dangerous. Tetsuo is destroyed from the inside-out by this growing mass as he becomes increasingly out of control, and nothing can prevent this from happening because it's a side effect of previous wrongdoings.

It isn't a coincidence that both the singularity event and the Big Bang that follow resemble the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagaski. As outlined by writer Joe Marcynzki at Little White Lies, the film explores the morality of nuclear weapons through the lens of the children that are secretly being subjected to parapsychological tests by Tokyo's government. One way to view the parallels: the children themselves are the atomic bombs, Akira was the inciting incident, and Tetsuo can be viewed as Japan itself, struggling with whether or not to continue the cycle of violence — a government responding to a horrific attack by committing atrocities of its own.

Is it morally acceptable to hide the existence of warheads from public knowledge? Should the public be alerted to rampant, often cruel testing that is going on behind the scenes? How does a governing body reconcile with the damage that has been done by its own hand in the name of survival? "Akira" doesn't outright answer those questions, but rather leaves it up to viewers to debate the morality of such horrors.

'Big people' cannot play God

Tetsuo's inability to reckon with the divine powers is his downfall, as humans are not equipped to play God because they will only act in their self-interest. Tetsuo, an insecure, impulsive young man, almost immediately uses his power to lash out at anyone who challenges his newfound skills.

Kiyoko, one of the few children to survive the government's secret testing, expresses to Tetsuo that "big people" shouldn't possess such powerful abilities because they are impure and will only act out of self-interest. Tetsuo, unable to control the powers he has unwillingly received, sets off on a violent rampage. He denounces the existence of Akira, whom he initially sought out, and becomes drunk with power until it overtakes him. In the final moments, his former insecurity returns along with his blatant terror.

The prophetic, religious elements of the story are complex, but the battle between childlike innocence and adult selfishness is constantly at play. Children shouldn't have to grapple with the notion of playing God, either, but their purity prevents them from abusing power the way adults would be inclined to.

Tetsuo's self-realization

As the decaying remains of Neo-Tokyo crumble under Tetsuo's epic destruction, water fills in the ruins as though the city never stood there. The impurity has been washed away and replaced by something clean. And Tetsuo is ... gone?

After being pulled into a separate dimension, both Tetsuo and Kaneda undergo what could be considered spiritual transformations. Kaneda, who is rescued by the espers, experiences each of their childhoods and sees the testing, as well as his friendship with Tetsuo. He re-enters reality back in Neo-Tokyo, where he mourns his friend and leaves the city.

Tetsuo, on the other hand, is saved by Akira himself. He reemerges in a new universe, where Akira will guide him on how to control these telekinetic abilities. His closing declaration of "I am Tetsuo" implies that he now understands the extent of his godlike powers. He has transcended into a new existence; with the right guidance, perhaps his power will no longer perpetuate the cycle of destruction that began with Akira. Or maybe it will go on to destroy another society.

There is much to grapple with in the ending of "Akira," and the discussion will likely carry on until the years-in-the-making live-action remake is finally released.