Things Only Adults Notice In My Neighbor Totoro

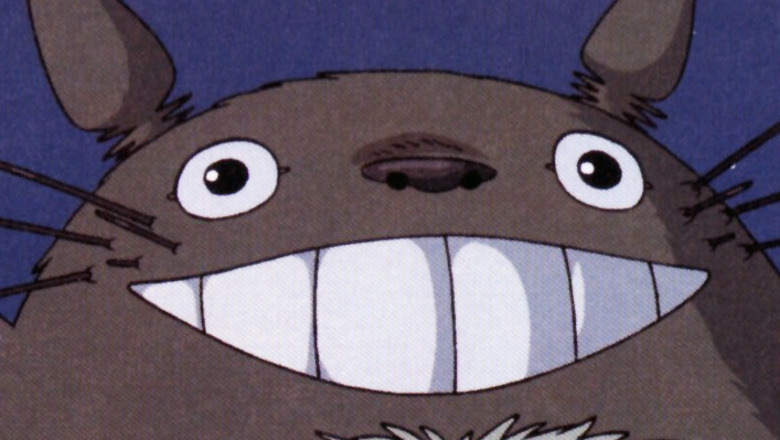

My Neighbor Totoro is something unique in the world of children's movies — or maybe it just takes what all children's movies are trying to do and does it better. The basics of the story are familiar: Two little girls, Mei and Satsuki, move into a new house and discover a magical world in the nearby forest full of strange spirits. But none of them are quite as memorable as Totoro himself. He's a huge, fluffy creature, somewhere between a bear, an owl, and a big shaggy dog. He's both a loving, protective father figure and kind of a big kid himself, full of curiosity and wonder.

Critics love to describe movies as "feel-good," but few of them wrap you up in warmth and contentment quite like My Neighbor Totoro. Master director Hayao Miyazaki made a masterpiece here — and that's saying something, considering he went on to direct Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, Ponyo, and many more classics than we have the space to list here. Totoro is the perfect movie for kids, but that doesn't mean it's just for them. There are depths within this movie that take adult experience to reach. Indeed, even a grown-up can find something new in Totoro every time they rewatch it. These are the artistic accomplishments, dark undercurrents, and deeper meanings we found looking at Totoro through adult eyes.

My Neighbor Totoro breaks the kids' movie formula

Totoro's rough outlines may align comfortably with the formula of other kid's fantasies, like Winnie the Pooh, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, and Lilo and Stitch. But Miyazaki fills in that outline in ways few other storytellers have ever dared to attempt.

Both Roger Ebert and Daniel Thomas find the best route to understanding Totoro is to look at what it isn't. Totoro's biggest departure isn't just from the rules of kids' movies, but from the first rule we ever learn about narrative: That it requires conflict. Until the devastating final act, there are no obstacles to overcome, and no real friction between the characters. Even the parents, who in any other fantasy would be grim killjoys denying the magic their children have discovered, are loving and nurturing. We can't be sure if Mei and Satsuki's father really believes in Totoro, but we know he sees no problem taking their reports at face value.

Ebert says it best: "Here is a children's film made for the world we should live in, rather than the one we occupy. A film with no villains. No fight scenes. No evil adults. No fighting between the two kids. No scary monsters ... A world where if you meet a strange towering creature in the forest, you curl up on its tummy and have a nap."

My Neighbor Totoro is a lesson in patience

My Neighbor Totoro's biggest departure from the kiddie movie formula isn't in the story itself, so much as the way it's told — specifically, the fact that it doesn't have much story at all. Most family flicks evince a desperate desire for kids' attention, frantically throwing loud noises and flashing lights in their face whenever they might be tempted to look away. Miyazaki accomplishes something much more difficult in Totoro: He makes the kind of stillness that typically has kids jumping for their video games not just interesting, but mesmerizing. You don't really notice how little happens, because you're so wrapped up in watching it slowly unfold. The thrills here aren't from fight scenes or explosions, but from the magic of sunlight on spring leaves.

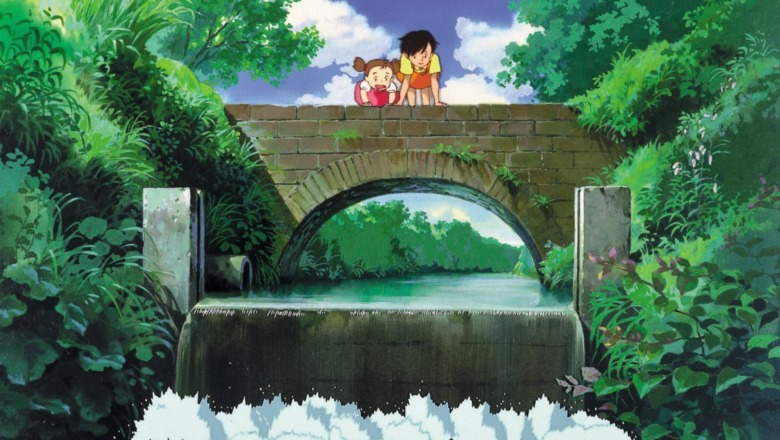

Miyazaki's not the first director to make a movie this way, even if he's one of the most successful. You can see the model for his technique in the work of Yasujiro Ozu, whose Tokyo Story was voted the third-best film of all time by Sight & Sound. Ebert summed up Ozu's style best by celebrating the director's so-called pillow shots: Images that don't have anything to do with the plot, but exist for their own sake. There are plenty of those in Totoro, depicting chimneys, rivers, rain, and other seemingly mundane sights. They have nothing to do with the story, but everything to do with the mood — and that's what really matters in Totoro.

It captures real kid behavior in ways only adults can see

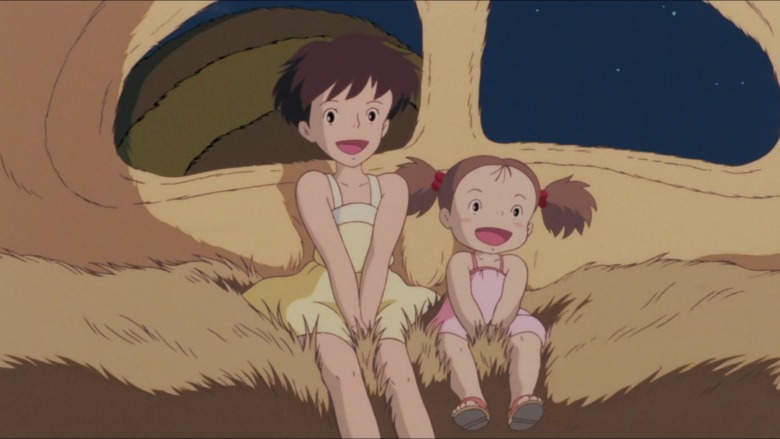

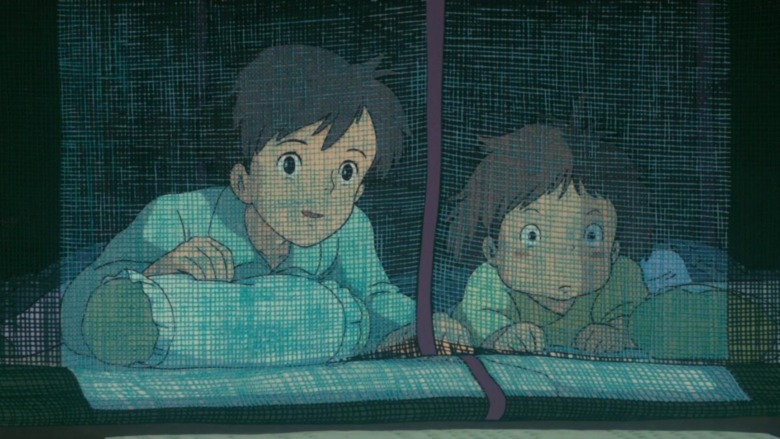

Mei and Satsuki would be more at home with real kids than with most of their cinematic peers. You never get the sense they're performing cuteness for an audience, for one thing. For another, Studio Ghibli's animation captures something true about childhood that most moves miss: Kids, having yet to fully absorb adult social norms, are weird.

This is the kind of thing you can only see in children once you're an adult. Kids, for example, don't get the same thrill of recognition adults do from scenes like Mei meeting Totoro for the first time. If an adult fell down a rock chute and landed on the stomach of a 10-foot-tall behemoth, they'd run screaming for the hills ... but Mei just asks his name. Then there's the way Satsuki turns looking for the stairs into a game, proudly announcing, "It isn't in here!" over and over again, while Mei runs behind her and does the same thing. Kids are goofy, strange, curious, and odd. Totoro captures that with unique honesty.

This honesty also applies to the portrayal of childhood's painful realities. When Mei breaks down crying when she thinks her mom might die, her mouth opens cartoonishly wide — but that exaggeration conveys a deeper emotional truth. Add in the animation of snot and tears running down her face, accentuated by Chika Sakamoto's earsplitting voice acting, and you've got an all-too-real portrayal of juvenile grief.

Death isn't totally absent from Totoro's innocent world

Totoro creates an untroubled world where viewers escape the tribulations of their real lives. But if that was all the movie offered, it would feel as false as every other milquetoast cartoon. Miyazaki understands that kids may not bear the weight of reality that adults do, but that the darkness of life, and even death, affects little ones as well, no matter how hard adults try to shield them from it.

The threat of death is always lurking under Totoro's placid surface. Principally, Mei and Satsuki move to the country because their mother is in the hospital. That threat finally emerges when Mei and Satsuki get a telegram that says their mother has taken a turn for the worse. This is stated clearly enough to get through to kids, but what they may not realize is how close Mei herself is to death when she runs away to the hospital. Kids are blissfully unaware of how helpless they are in the dangerous world, but adults are painfully aware of it, especially if they have kids of their own. Thus, what seems like standard movie peril to kids is downright harrowing to adults. That's especially true when Granny finds what she thinks is Mei's sandal floating in the lake. Most kids won't grasp the terror this induces in adults, but it's hard for their elders to miss, especially when we see the neighbors dragging bamboo sticks through the lake.

My Neighbor Totoro takes place in a dark time for Japan

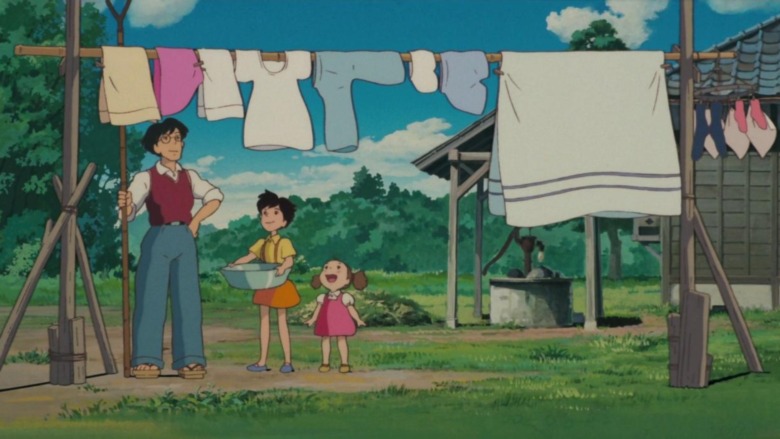

At first glance, Totoro seems to take place in the same timeless, rural world so many other children's stories do. But adults should be able to spot Miyazaki's hints that he's making a period piece: Consider the fact that the girls wash laundry by hand (or foot) and hang them out to dry, and that the phone Satsuki uses to call her dad looks like it might belong to Alexander Graham Bell. Other critics have placed Totoro in Miyazaki's own postwar childhood, and Miyazaki himself narrows it down to 1955 in The Art of My Neighbor Totoro.

As anyone who knows their history can tell you, this wasn't a good time for Japan. The country was still reeling from the devastation of World War II, a time Studio Ghibli chronicles in heart-wrenching detail in Grave of the Fireflies, which screened alongside Totoro in its initial release. Even a decade after the war's end, the strain of rebuilding, the end of imperial rule, and the Allied occupation had Japan in a state of upheaval. Totoro's carefree setting coexists with all that painful transition. Knowing where that transition goes adds an even more melancholy subtext to the movie: As Den of Geek points out, Totoro's untouched forest isn't long for this world. The following decades of Japanese history would bring the country rapid industrial progress and environmental ruin.

The animation of the tree evokes some traumatic history

To thank Mei and Satsuki for lending him their umbrella, Totoro gives them a bundle of seeds "wrapped in bamboo leaves and tied with dragon whiskers." One night, Totoro comes back with the umbrella and his little cousins to lead Mei and Satsuki in a magical ritual that makes the seeds grow into an enormous tree. It's a beautifully animated scene that somehow makes the tree appear liquid in its constantly changing shape, without ever losing the solidity of the heavy, earthy wood.

In 100 Animated Feature Films, Andrew Osmond makes a startling suggestion about Miyazaki's imagery in this scene. He draws a parallel between the blooming, expanding tree and the mushroom cloud of the atomic bombs that destroyed the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This may seem like a stretch at first glance, but if you look at the scene again with that in mind, it's impossible not to see it. Miyazaki takes this very innocent, un-traumatic film and uses it to rewrite his generation's defining trauma. The scene is beautiful as it is, but it's even more impactful when you see what he's doing: Taking a symbol of death and turning it into one of rebirth, thus transforming destruction into creation.

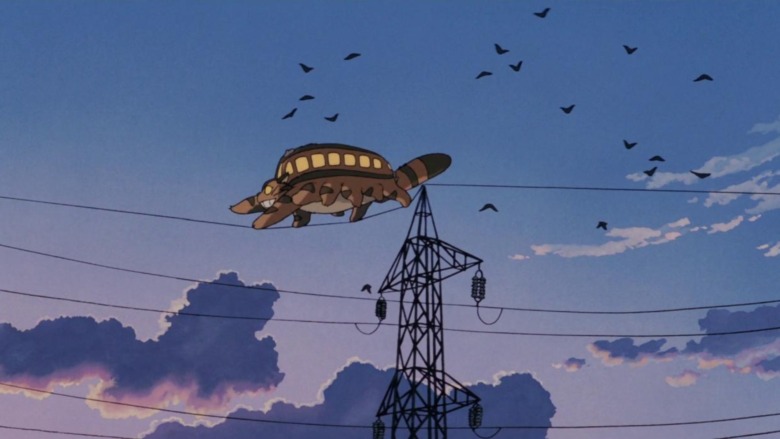

A bus really would seem magical to these kids

Totoro's themes of progress are most obvious in the Catbus, one of the film's most beloved characters. The Catbus is just what its name implies: It's an enormous, magical cat who runs on 12 legs, with headlight eyes and windows that turn into doors to welcome passengers aboard. The film drops several hints that adults could see everything Mei and Satsuki do if they'd only look. But Totoro is still a story of imagination, even if its magic is somewhat real within its world, and it's easy to see why the Catbus would be a figure of fantasy within this postwar setting.

Modern travel took a while to hit Japan. In the 1950s, the era in which Totoro takes place, few of the country's roads were paved to accommodate motor traffic. In that context, a bus really would seem just as magical as a 12-footed cat to two girls who'd never seen one before. The Catbus is also a modern version of a very old myth: Miyazaki drew on legends of mystical cats like the shapeshifting bakeneko and the monstrous nekomata in creating it. He makes this connection clear in the art book, revealing the backstory he invented for the Catbus: "The [Catbus] once assumed the shape of a rickshaw carrier, but the sight of a bus rumbling by excited it so much it turned itself into one."

The wrong kid's on the poster

The original Japanese poster for My Neighbor Totoro has become iconic. It recreates the scene of Totoro, with a leaf on his head and a hilariously blank expression, appearing at the bus stop. There's one key difference you may notice, though — instead of Mei and Satsuki beside him, the original image just shows one girl, who looks like a cross between the two sisters. She's not quite as old as Satsuki, or as young as Mei, and sports pigtails. Let's call her Meisuki.

So what happened? There's actually a surprisingly logical reason for this apparent goof. Miyazaki originally developed Totoro with just one protagonist, until he realized that his four-year-old character couldn't realistically be independent enough to do everything his story called for. So he gave his heroine an older sister to take care of her. This very scene ended up inspiring the change: As Miyazaki once said, "If she was a little girl who plays around in the yard, she wouldn't be meeting her father at a bus stop, so we had to come up with two girls instead." We don't have the paper trail to confirm what led to the episode of poster miscommunication, but Poster Pagoda does offer some of Miyazaki's concept art, depicting this scene with just one girl that seems likely to have been the basis for the poster.

The script is full of bilingual wordplay

Miyazaki may have been tossing in a little in-joke for his coworkers and fans in the know when he named Mei and Satsuki, but only bilingual viewers will catch it. As previously established, Mei and Satsuki began as one character, later split into two sisters. Believe it or not, they both retained the same name — sort of. As Dani Cavallaro notes in The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki, Satsuki is the traditional Japanese word for the month of May, and "Mei," of course, is pronounced as "May" is in English.

That's not the end of Miyazaki's wordplay. Satsuki describes Totoro as being "just like in my picture book," though no such book exists. In fact, Totoro is a totally original Ghibli invention who takes his name from the English word "troll." Sharp-eyed fans will notice another original creation in the house's soot sprites. In the original Japanese, they're called "susuwatari," which means "wandering soot," or "makkuro-kurosuke," a compound of "kuro" (black) and "makkuro" (jet-black). They were obviously too good a creation to only use once — you can see them again in Ghibli's rapturous Spirited Away, made almost 20 years later.

The characters have gravity-defying hair

The animation in My Neighbor Totoro is remarkably lifelike. But sometimes, Studio Ghibli conveys the characters' emotional reality by departing from their literal reality. They use some of the same tricks otaku will recognize from other anime: Most obviously, characters' mouths can expand to take up most of their faces, or vanish altogether when they're closed. But there's another, subtler trick pulled off with the characters' hair, which seems to float and ripple to emphasize their emotions.

Once you notice this, you'll see it everywhere. It's present when Mei and Satuski yell to scare the soot sprites, and when Satsuki cries after getting the telegram. When Mei sticks her finger in a soot sprite nest, her hair and skirt stand straight up, like they're being electrified. Even Totoro gets in on the act, his fur frizzing like a cat's to show how much he enjoys the sound of rain falling on his umbrella. Gravity-defying hair has become a Miyazaki trademark you can spot in nearly all his films. Perhaps the most memorable use of this visual device occurs in Howl's Moving Castle, when Howl's hair floats as he calls up dark spirits.

Satsuki almost sees Totoro before she meets him

One result of Totoro's leisurely pace is that Totoro himself doesn't actually show up until over half an hour into the movie — and another 20 minutes pass before he meets Satsuki. At least, that's the way it seems on the surface, but Dani Cavallaro makes an intriguing observation that suggests this might not be true. Totoro's magical creatures are connected to the invisible force of the wind: When the Catbus races to find Satuski near the end, it runs right past two oblivious adults, who only react to the wind the Catbus kicks up. Recall also the scene in which Totoro takes the girls for a ride on his flying spinning top, during which Satsuki says, "We're the wind!"

With those two scenes in mind, take another look at the earlier scene of the windstorm. It's a perfect metaphor for the whole movie: The girls sit in their cozy home while something dark and terrible rages outside. Or maybe it's not so terrible after all — the storm begins with a gust of wind that churns the grass like the ocean and scatters Satsuki's firewood. She looks up like she sees something — could it be Totoro?

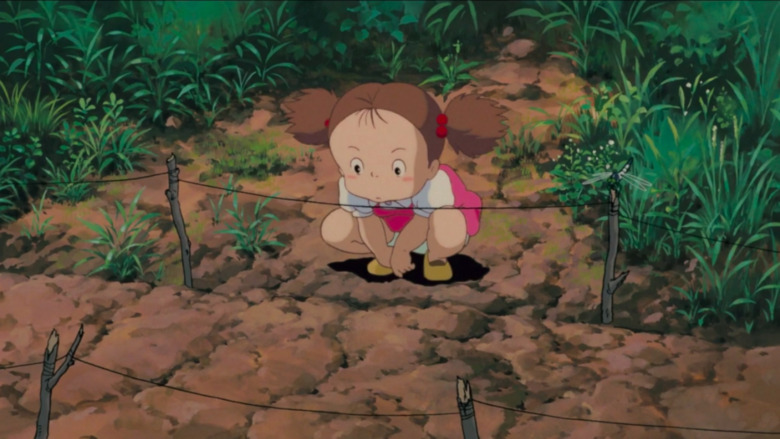

Satsuki has a specific crab in mind when she describes Mei

When the girls receive their seeds from Totoro, Mei parks herself in the dirt where they planted them with a look of adorably intense concentration on her face, as if they'll grow right in front of her. In her letter to their mother, Satsuki says Mei looks just like a crab, and even includes a doodle as a visual aid. She does indeed look crustacean-ish, with her knees splayed out like a crab's legs and her arms hanging down like claws. But to Totoro's original Japanese audience, this scene has an added meaning. As Cavallaro points out, Miyazaki has a specific crab in mind who would have been familiar to his domestic audience: The crab from a popular folktale involving a crab and a monkey.

In this story, a crab with a rice dumpling meets a monkey who has nothing to eat but a persimmon seed. The jealous monkey tricks the crab into trading him the dumpling for the seed, convincing him that he may enjoy the dumpling now, but the persimmon seed will grow into a tree and provide him much more food in the future. But the monkey has outsmarted himself: The crab really does plant the persimmon seed, and sits and waits for it to grow, just like Mei.