The Untold Truth Of Studio Ghibli

It's challenging to find anyone today who isn't familiar with the works of Studio Ghibli, even if they aren't into other Japanese films, animated or otherwise. The round-faced, expressive characters that populate Ghibli's films are instantly recognizable, whether they hail from kid-friendly fare like My Neighor Totoro or mature offerings like Princess Mononoke. And while Ghibli films have been available to North American audiences for a while now, it wasn't until 2001's Spirited Away made it to Western cinemas that the studio really got the attention of American audiences, especially after it took home the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.

But the groundbreaking animation work of Studio Ghibli goes all the way back to its founding in 1985. And the studio's scope goes well beyond your typical kiddie flick, as these movies appeal to audiences of all ages with timeless themes of determination, environmental justice, and the empowerment of the young. In other words, it's totally worth diving a bit deeper than Totoro and Spirited Away to get a look at some of the untold truths of Studio Ghibli.

The truth behind the studio's name

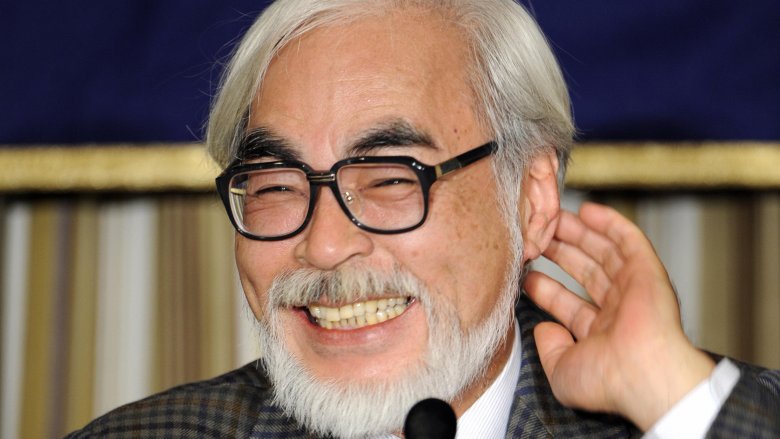

"Studio Ghibli" is a pretty unique name, but it doesn't sound particularly Japanese. That's because the name's origin lies in more Mediterranean climes. The term "ghibli" is an Italian adaptation of a Libyan-Arabic word that refers to the hot, dry winds in the desert. The idea behind choosing this name came from Hayao Miyazaki's desire to revitalize the animation industry, like a wind blowing through and stirring up change.

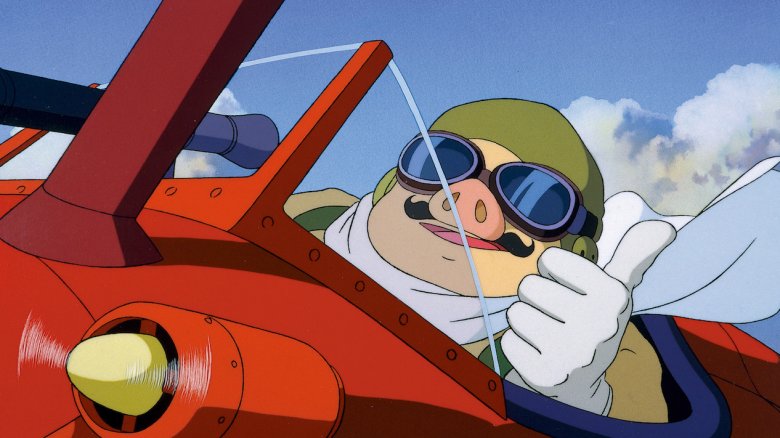

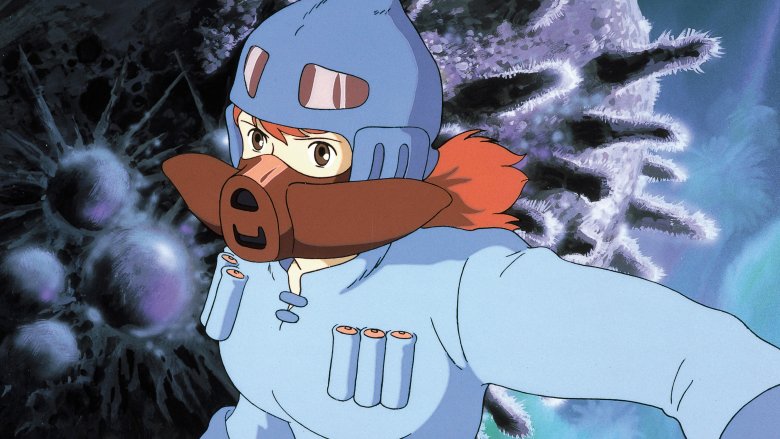

Ghibli is also the name of an Italian transport aircraft manufactured by a company called Caproni, and that's probably not a coincidence. Miyazaki's fondness for World War II-era aircraft is no secret if you've seen his films, especially Porco Rosso, which takes place in Italy during the rise of fascism, and The Wind Rises, which follows the exploits of real-life plane designer Jiro Horikoshi during wartime. Even his films that don't focus specifically on war-torn Axis powers and their flight advancements belie Miyazaki's passion for the themes of flight. Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind is an excellent example of Miyazaki taking his knowledge of aircraft and using it to construct a fictitious hovercraft. And blimps and fighter planes are prevalent in Castle in the Sky and, to a lesser extent, in Kiki's Delivery Service (which, of course, also features some incredible broom-flight sequences). In other words, this dude loves flying.

Studio Ghibli is more than Miyazaki

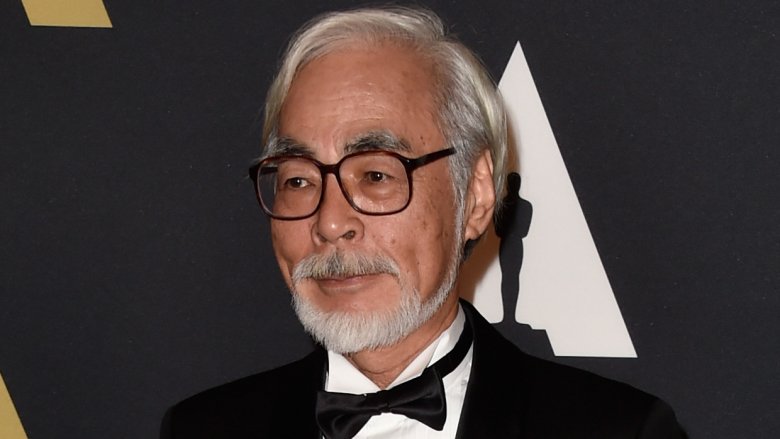

Studio Ghibli is far from being a one-man operation. Though Hayao Miyazaki is far and away the most prolific and most well-known of Ghibli's founders, the truth is that the studio was started up by four men: Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, Toshio Suzuki, and Yasuyoshi Tokuma. Suzuki and Tokuma were mainly producers, but Takahata, who passed away in April 2018, directed incredible features on the studio's behalf. His best-known work is the heart-wrenching, semi-autobiographical tale of post-war Japan, Grave of the Fireflies. This film is famously difficult for viewers to endure, and while it's widely regarded as a masterpiece, it's not exactly high on anyone's rewatch list.

Takahata didn't focus solely on tragedy, though his sense for the melancholic and dramatic was very strong. In 1994, Takahata took a turn for the whimsical with Pom Poko, which depicts the antics of a group of tanuki (Japanese animals similar to raccoons, which are rumored to have magical abilities) trying to reclaim their land from greedy developers. Even with the humorous angle of the sake-loving, transforming tanuki, the theme of the film is heavy: Mankind is destroying the natural habitats of countless animals. Most recently, Takahata adapted The Tale of Princess Kaguya, based on the 10th-century story The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. It's a beautiful, flowing film done in an ink-brush style that benefits from Takahata's excellent flair for melancholy, and it's proof that Ghibli is more than just Miyazaki.

There are plenty of guest directors working with Studio Ghibli

Though Miyazaki and Takahata have historically been the studio's in-house heavy hitters, Studio Ghibli has brought on other directors for some of their projects. Miyazaki's son, Goro Miyazaki, directed Tales from Earthsea, a loose adaptation of the first four books of Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea series of novels. In 2011, he came back to direct From Up on Poppy Hill, a period piece set in 1964 that focuses on a group of high schoolers who fix up an old school clubhouse and prevent its demolition, once again utilizing themes of pushing back against the blind pursuit of progress.

In 1995, Yoshifumi Kondo made his directorial debut with the playful coming-of-age film Whisper of the Heart. He was well on his way to succeeding Miyazaki as Ghibli's next big director, but unfortunately, he died in 1998 of an aneurysm before he was able to direct anything else. Seven years later, Hiroyuki Morita picked out a minor character from Whisper of the Heart and spun a sort-of sequel, The Cat Returns. And Hiromasa Yonebayashi, who would later go on to co-found Studio Ponoc, directed the 2010 film The Secret World of Arrietty (based on Mary Norton's novel The Borrowers) and 2014's When Marnie Was There. In other words, there's no shortage of directorial talent over at Studio Ghibli.

Joe Hisaishi's musical contributions

A good deal of what makes any Studio Ghibli film memorable is the incredible musical scores. Veteran composer Joe Hisaishi has worked on the majority of Miyazaki's film scores, and fans can instantly recognize songs like "A Town With an Ocean View" from Kiki's Delivery Service or the jaunty, bouncing opening theme to My Neighbor Totoro, aptly titled "Stroll." The majority of Hisaishi's work has been on Miyazaki's films, but he has had a few opportunities to branch out, as well. He's worked very closely with director Takeshi Kitano on his live action films Sonatine, Kids Return, Hana-bi, Kikujiro, and Brother, many of which are crime dramas. He's also had a hand in video game scores for Ni no Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch and Ni no Kuni II: Revenant Kingdom. Though soundtracks take up the bulk of his portfolio, he's also released multiple studio albums, beginning in 1981. Basically, when it comes to catchy tunes and emotionally moving music, Joe Hisaishi is the man.

The studio has a no-edits policy

In 1997, Studio Ghibli struck a deal with Disney to distribute some of their films to English-speaking audiences. Part of this deal involved a stipulation that their movies wouldn't be edited in any way or for any reason. Famously, producer Harvey Weinstein wanted to edit Princess Mononoke for better marketability, but in short order, Miyazaki sent him an authentic samurai sword with a note reading only, "No cuts."

Miyazaki also has a reign on any merchandising rights, preventing there from being an onslaught of cheap, chintzy, Ghibli-based toys in the American market. These policies might seem restrictive, but they've allowed these incredible films to be viewed the way they were intended. Miyazaki wants to keep the focus on the narrative and the characters. He wants people to appreciate Ghibli films as influential and important pieces of art, movies that aren't watered down by concentrating exclusively on market appeal. And yet the Ghibli films do have market appeal, and they've proven time and time again to touch the lives of audiences all over the world, even without being forced into the most easily-digestible Hollywood mold.

There's a Ghibli Museum

Though Ghibli has their deal with Disney, they've opted against the Disney theme park model. What they have instead is the Ghibli Museum, located in Mitaka, Tokyo, and about 20 minutes away from the studio in Koganei. This incredible museum invites guests to experience the exhibits fully, asking that they don't photograph anything in favor of engaging with their surroundings. Upon paying their fare, tickets guests receive actual pieces of original 35mm film used in theaters, and guests can hold their tickets up to the light to see what classic Ghibli scene they've acquired. The museum runs exclusive short film projects in their small theater, and has a reading room for attendees to browse through books selected by Miyazaki himself. After taking in all the various exhibits full of production art and cel sheets, guests are invited to browse the gift shop, called "Mamma Aiuto" ("Mama, help me," in Italian) after the airship pirates from Castle in the Sky. The grounds also house an impressive statue of a robot soldier from Castle in the Sky, as well as an enormous stuffed Catbus from My Neighbor Totoro for young fans to enjoy.

Ghibli isn't afraid to co-produce with other studios

Studio Ghibli's standards for their own work are clearly very high, but this hasn't prevented them from collaborating with other studios on projects. In 2014, Miyazaki's son Goro set out to direct his first anime series, Sanzoku no Musume Ronya, a computer-animated adaptation of Astrid Lindgren's fantasy tale Ronja, the Robber's Daughter. This was a project for Nippon Hoso Kyokai (NHK), Japan's national public broadcast station, and it was produced by Polygon Pictures and co-produced by Studio Ghibli. Yeah, that's quite a bit of collaborating right there.

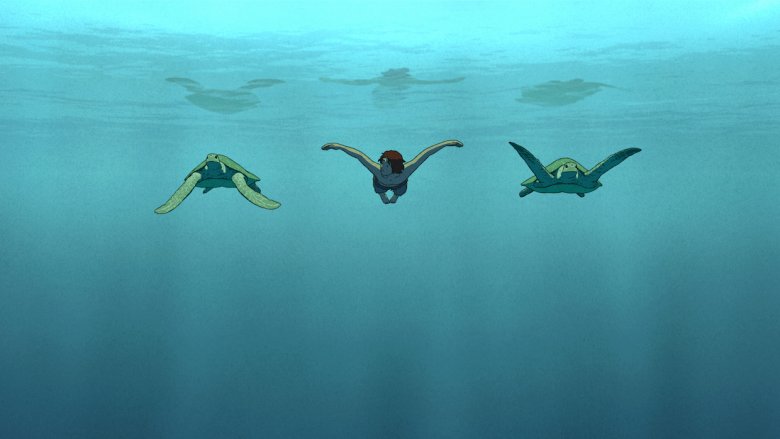

Just two years later, Ghibli teamed up with the German company Wild Bunch to produce The Red Turtle, co-directed by Dutch animator Michaël Dudok de Wit. The film is silent and short, running just 80 minutes, and it tells the tale of a man stranded on a resource-rich island. However, every time he tries to escape, he's thwarted by a large red turtle. It was nominated for the Best Animated Feature at the 89th Academy Awards, and while it was beaten by Zootopia, the movie still deserves all the praise for its touching story and gorgeous visuals.

So many legends have worked with Ghibli

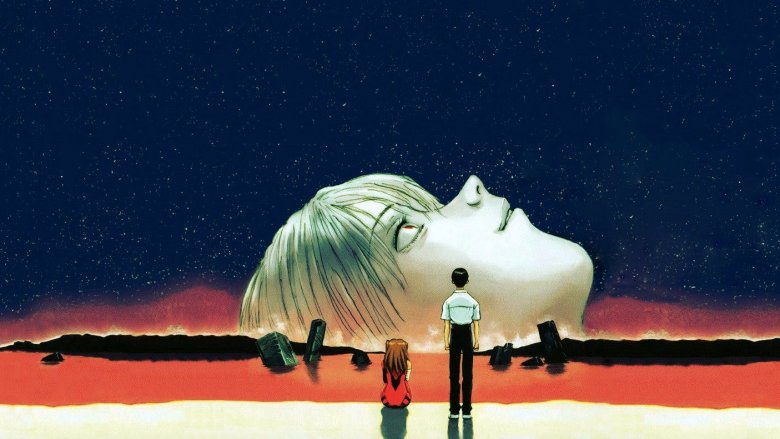

As it's one of the most prestigious studios on the planet, it should come as no surprise that plenty of famous and influential animators have made their way through Ghibli's roster of employees. Most readily recognizable is Hideaki Anno, the creator of the science-fiction robot series Neon Genesis Evangelion. His contributions to Ghibli include animation on Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (which technically predates the studio's founding) and Grave of the Firefiles, as well as acting as protagonist Jiro Horikoshi in The Wind Rises.

Kitaro Kosaka had a hand in many Ghibli films, from Nausicaa right through The Wind Rises. But Kosaka also provided animation for beloved films and series such as Akira, Master Keaton, and Monster. Makiko Futaki, whose portfolio is Ghibli-heavy, also lent her animation skills to Akira. And Masashi Ando had the opportunity to work closely with another impressive and influential director, the late Satoshi Kon, providing character designs for Paranoia Agent and Paprika, as well as animation for Tokyo Godfathers.

However, working at Studio Ghibli might not be as whimsical as watching their movies. According to former employee Hirokatsu Kihara, Ghibli is a stressful, somewhat restrictive place to work. That's disappointing to hear, but it can't be denied that some of Japan's best animation talent has been through the studio and come out with great successes to their names.

A focus on female protagonists, not female directors

It's obvious that Hayao Miyazaki particularly favors young female leads in his films. He's been asked about this predilection many times, and while his answers vary from "girls make better protagonists" to "I just like girl characters," viewers get the sense that he's really interested in telling stories from a new perspective, a perspective vastly different from his own. Many women and girls look up to strong-willed characters like San or Lady Eboshi from Princess Mononoke, or they identify with Kiki's struggles to find her own special talents in Kiki's Delivery Service. At a time when Disney was churning out countless princess films depicting a very specific view of femininity (not counting Mulan), it was refreshing to have some balance with Ghibli girls who weren't necessarily tomboys, but who balanced their girlhood with interests or preoccupations outside of the expected.

Up until this point, however, Studio Ghibli has not featured any female directors. In fact, Hiromasa Yonebayashi, who was Ghibli's president for a time, even stated that he didn't believe women were suited to directing fantasy films. His reasoning was that women are practical and realistic, while men are natural-born dreamers. Of course, this is utter nonsense, and it's deeply disappointing coming from a production studio that has had such an influence on the dreams of young girls.

Studio Ghibli loves its environmentalist themes

When it comes to thematic elements and powerful messages, Studio Ghibli films often focus on subjects like environmentalism and the drawbacks of unchecked progress. These themes are readily obvious in movies like Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, where Nausicaa lives in a post-apocalyptic world populated by the giant isopod-like Ohmu, with whom she learns to communicate. These themes are also pretty obvious in Princess Mononoke, where San, raised by wolf gods and identifying more as a wolf than a human girl, pushes back against Lady Eboshi's hunt for the forest spirit, with Eboshi's rifle serving as an analogy for unchecked progress.

But Miyazaki isn't the only director with these concerns. Isao Takahata's Pom Poko is very deliberate in its depiction of tanuki being forced to fight back against land developers who are pushing them out of their habitat. For a film chock-full of adorable animals, hilarious gags, and a great dose of whimsy, it ends on a despondent note, acknowledging that there's no happy ending when humanity seeks to control all of nature's resources. Plus, Goro Miyazaki directed From Up on Poppy Hill, which focuses less on environmental issues and more on protecting and utilizing institutions of the past, rather than pressing forward with progress for the sake of progress. The screenplay was, however, co-written by Hayao Miyazaki, so perhaps the theme shouldn't be a surprise.

Studio Ghibli versus Studio Ponoc

In 2015, former Studio Ghibli film producer Yoshiaki Nishimura founded Studio Ponoc. He borrowed the name from the Croatian word for "midnight," intending to signal the "beginning of a new day." One wonders if this is a direct dig at Ghibli by showing a desire to break away from the formulas that the older studio had developed.

Following Nishimura from Ghibli was Hiromasa Yonebayashi, who's directed both of the new studio's films thus far: Mary and the Witch's Flower and the anthology film Modest Heroes. Though Yonebayashi reportedly said that he wanted his Studio Ponoc films to be the "opposite" of his very last Ghibli joint, When Marnie Was There, audience members may notice striking similarities between that film and Mary and the Witch's Flower. The animation style borrows liberally from that established by Studio Ghibli (and Miyazaki in particular). The young studio only has a couple of works under its belt thus far, so it will be interesting to see how they manage to break the mold of their predecessors and continue to change the Japanese animation landscape for the future.

Will Miyazaki ever retire?

For many fans, Hayao Miyazaki is practically synonymous with Studio Ghibli. He's a founding member of the studio, as well as its most prolific creator and director. But even he can't live forever, and he's threatened retirement time and time again. The Wind Rises was supposed to be his final feature film for Ghibli, and it would've been a fitting send-off. It tells the story of a young man overcoming countless odds in wartime, all while questioning his career and his choices over and over again.

One imagines that Miyazaki identifies with protagonist Jiro Horikoshi to some degree, which would make The Wind Rises a deeply personal film for him. But it seems that Miyazaki can't decide what to do with himself in retirement, so now the septuagenarian artist is back at the literal drawing board. It's said that the man came out of retirement so he could create a film for his grandson. So what is his next movie going to be? Well, he's directing a Ghibli feature called How Do You Live?, set to come out in 2020. The film is named after a 1937 novel that features prominently in the main character's life — though that's about all we know regarding this new project. We'll have to wait and see whether How Do You Live? will actually be his final film, or if Miyazaki will keep working for (hopefully) many more years to come.