Wildest Giant Monster Fights In Movies

When it comes to monster movies, all the talented actors and top-shelf special effects don't mean a thing if you don't deliver some spectacular kaiju-on-kaiju fight scenes. After all, watching two colossal creatures battling for supremacy is a primal satisfaction on par with enjoying the most delicious comfort foods.

And ever since massive beasts started showing up on the silver screen, monster fans have had their favorite fights, ranging from everybody's favorite oversized ape battling a T. rex in 1933's King Kong to Ray Harryhausen's Cyclops wrestling with a dragon in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. But then, there are the lesser-known and left-field monster fights, the ones where the strings and suit stuffing are showing or the ones that feature the least probable or most bizarre opponents.

These action scenes aren't masterpieces, but they stand out by virtue of their outrageousness, violence, or ineptitude. Even though these scenes aren't perfect, we love them for trying — or pretending to try. So get ready for some titanic battles as we take a look at the wildest, weirdest giant monster fights in movies.

Does The Black Scorpion feature a lost Kong fight scene?

There's just one monster fight in 1957's The Black Scorpion, but it's a doozy, and it even comes with a bit of a legend. The black-and-white creature feature by journeyman director Edward Ludwig concerns giant prehistoric scorpions in Mexico, whose appearance coincides with the formation of a new volcano. The scorpions themselves are hideous and aggressive carnivores, but the movie's pièce de résistance is a visit to the creatures' underground habitat. There, hero Richard Denning (and the audience) is treated to an onslaught of stop-motion monstrosities, including a stampede of scorpions that battle and devour alive a giant, tentacled worm before an even bigger scorpion emerges to polish off the victor with a ruthless stab of its stinger.

The impressive effects were supervised by Willis O'Brien, who created the groundbreaking stop-motion effects in the 1933 King Kong, and animated by Pete Peterson, who collaborated with Willis (and Ray Harryhausen) on the Oscar-winning Mighty Joe Young, among other films. Show biz apocrypha has long claimed that the worm and a trap door spider model that briefly appear in the scene were either holdovers from or inspired by models that O'Brien created for the infamous "spider pit" sequence that was trimmed from Kong. That's never been proven, but for Kong and classic sci-fi fans that have dreamed of seeing that lost footage, Black Scorpion is the next best buggy thing.

War of the Gargantuas is a king-sized sibling rivalry

If the giant monster fights in Toho's Godzilla series are the kaiju equivalent of a heavyweight boxing fight –- hard-hitting but lumbering –- then The War of the Gargantuas is the brutal street fight of the Japanese fantasy-science fiction subgenre. The 1966 feature -– a sequel of sorts to 1965's Frankenstein Conquers the World -– concerns two giant humanoids whose familial connection (both are spawned from mutated cells sloughed off from the previous movie's Frankenstein Monster) isn't enough to keep them from spending most of the film's running time beating each other senseless.

The battles between Sanda, the peaceful brown monster, and his ferocious green brother, Gaira, stand out from the rest of the Toho fight club for their sheer physicality. Haruo Nakajima (the first actor inside the Godzilla suit) and fellow suitmation actor Yu Sekita aren't restrained by layers of latex, and their fights have a speed and savagery that are largely unmatched by other Toho titles. The Gargantuas pummel each other mercilessly, use plenty of illegal holds and moves (Gaira is a biter), and decimate Eiji Tsuburaya's intricate sets with abandon. Their fights also have an amusing layer of familial aggravation, as evidenced by the scene in which Sanda discovers that Gaira has dozed off after eating a group of hikers, so he uproots a tree to thrash his snoozing brother.

Hammer goes haywire in The Lost Continent

Though England's Hammer Film Productions is best remembered for its long-running Dracula series, the company also took forays into other genres, including science fiction. Several of these efforts were taut, well-crafted features, most notably 1955's The Quatermass Xperiment. Of course, others were curiosities, like 1968's The Lost Continent.

Based on the 1938 novel Uncharted Seas by author Dennis Wheatley, Continent – which was written, produced, and directed by Hammer executive Michael Carreras – concerns a disparate group of ocean travelers who become stranded in an unknown region populated by living seaweed and descendants of the Spanish conquistadors under the leadership of a boy king (future British rocker Darryl Read). If that sounds like an unfocused mess, it is, but Lost Continent is also entirely watchable from a "what will they throw at the viewer next?" perspective.

And for two scenes, the film's answer to that question is giant sea creatures –- specifically, a king-sized octopoid monster and a giant hermit crab that, after dispatching the ship's bartender, has a grisly showdown with an equally sizable scorpion. Their fight is hampered by the special effects –- the two monster puppets are stiff and awkward –- but it's certainly a high point of lunacy in an altogether offbeat film

Gamera vs. Guiron is a cut above giant monster brawls

Giant monster fights can sometimes get bloody –- Godzilla spouts fountains of gore during his struggle with his robot double in Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla –- but they rarely stray into gruesome or sadistic territory. One notable exception is the incredibly dark bit of violence in Gamera vs. Guiron, the fifth of Daiei Film's adventures featuring the giant turtle. Save for its first entry (1965's Gamera, the Giant Monster), the Gamera series was known as a kid-friendly franchise that emphasized big but relatively G-rated brawls. Not so for Gamera vs. Guiron, though this foray into the gruesome is relegated to one brief but completely jaw-dropping scene.

Gamera's foe this time is Guiron, a giant reptile of sorts whose primary distinguishing feature is an enormous head shaped like a kitchen knife. Gamera gets the business end of that head on several occasions, but being top billed, he's not forced to suffer ignominy on top of injury. That falls to the pterodactyl-like Gyaos, a recurring heel in the Gamera universe and one who makes the grave error of misjudging Guiron's carving capability. After using the flat edge of the blade to send Gyaos' beam back at him and lopping off his leg, Guiron cuts off the poor creature's wings before decapitating the still-conscious monster. And then, Guiron slowly and methodically slices Gyaos' torso into sections while issuing a deep, carnival-nightmare laugh.

11 giant monsters fight it out in Destroy All Monsters

Intended as the final entry in Toho's original run of Godzilla films, 1968's Destroy All Monsters is by no means a perfect film. Its pace is at times sluggish, and it struggles to keep its human and monster storylines moving in tandem. But complaining about the film's shortcomings is a bit like kvetching over the calorie content of a juicy cheeseburger. No matter what perceived faults, Destroy All Monsters is still chock full of 100%, Grade A, satisfying giant monster mayhem.

Not only does it offer the second largest number of Toho kaiju in a single film — 11, including Godzilla and King Ghidorah, and surpassed only by 2004's Godzilla: Final Wars –- but it also showcases all of them in a no-holds-barred brawl that closes the film. The sheer logistics of coordinating the fight, which required not only suitmation performers like Haruo Nakajima (as Godzilla) but also an army of puppeteers in the Toho studio rafters operating wires for Ghidorah and Rodan's wings and all of the creatures' tails, is dizzying to consider. But director Ishiro Honda not only executes the fight with astonishing dexterity but also makes it exciting enough to stand up and cheer.

Can the Mighty Gorga beat up a kid's toy dinosaur?

Many an aspiring filmmaker's career began by staging their own action or science fiction epics with toys standing in for the human players or otherworldly creatures. That's perfectly acceptable for school-age kids ... but decidedly less so for a movie intended for a paying audience. But in the case of 1969's The Mighty Gorga, that's exactly what viewers got — a fight, in the broadest sense of the word, between the world's rattiest ape suit (with crossed eyes, no less) and what's basically a plastic Tyrannosaur toy with a snapping, flapping jaw.

Faced with what can only be considered a lose-lose proposition, co-writer/producer/director David L. Hewitt, who later designed special and optical effects for Willow and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, chooses frenzy over finesse and has the actor in the Gorga suit flail convulsively with the dino-toy until shoving it out of frame and dispatching it with a few stomps. The rest of Mighty Gorga, which concerns a circus owner's attempt to catch the colossal ape for his failing business, hews along these threadbare lines. The movie does feature one brief flash of special effects aptitude with the appearance of a dragon in a cave, but the footage is actually lifted from the 1960 sword-and-sandal film Goliath and the Dragon.

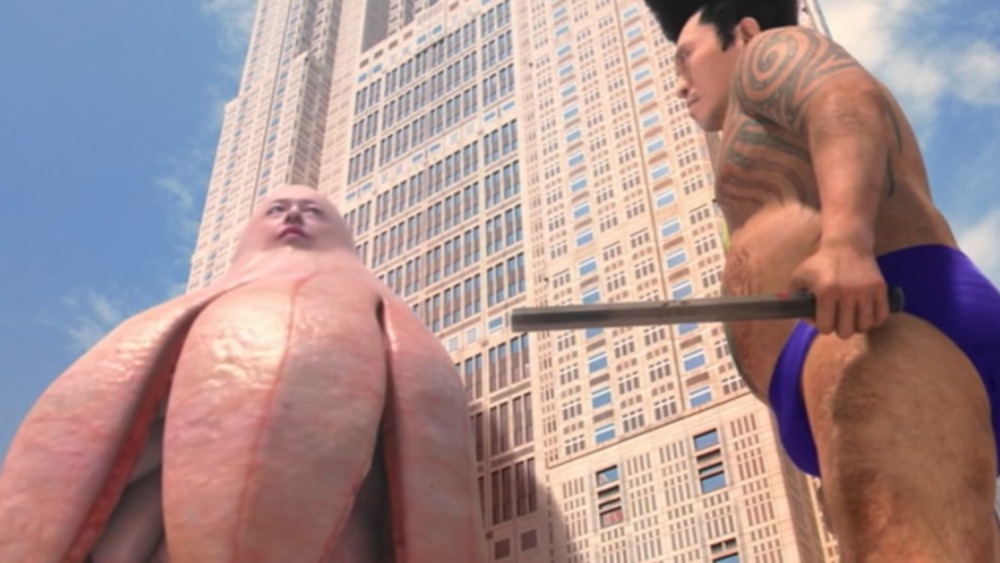

Daigoro vs. Goliath vs. the Bathroom

To be perfectly honest, the fights in Daigoro vs. Goliath aren't particularly wild. But it's context that distinguishes this 1972 Japanese fantasy-comedy –- a co-production between Toho, home of Godzilla and friends, and former Toho special effects creator Eiji Tsuburaya's eponymous production company -– and what you have in Daigoro is your only chance to see a potbellied dog/otter monster awkwardly brawl with a equally out-of-shape blue alien creature.

Yeah, you read that correctly, and before you ask, yes, Daigoro is aimed strictly at younger audiences who, by 1972, made up the majority of the moviegoing audience for kaiju films. Toho and Tsuburaya banked on the idea that a monster movie that was unequivocally for kids would be a windfall, and so they crafted Daigoro, the mild-mannered offspring of a monster killed by the Japanese military. Much of the film's running time is taken up with a core group of Daigoro's supporters urging him to get up the gumption to fight the rampaging space creature Goliath, which takes three long, pratfall-filled rounds before he summons up his mother's ability to breathe fire and best his opponent.

But in the interest of full disclosure (or warning), it's important to note that a significant portion of Daigoro is also devoted to its namesake's digestive habits, and the film closes with his visit to a skyscraper-sized outdoor bathroom. Again, you did read that correctly.

Martians meet their match in War God

A movie about giant, city-destroying aliens qualifies as awesome, without question. The same would apply to a movie about a king-sized, spear-wielding warrior. So a film about giant aliens fighting a huge warrior would be, in no uncertain terms, more awesome that anything previously considered. Said movie exists — it's a 1976 Taiwanese feature called Zhan shen, but it's known in English-language circles as War God or The Big Calamity, and it pits a trio of stubby but sizable Martians bent on ruining Earth for its nuclear arsenal against a gigantic manifestation of the 2nd-century Chinese warrior turned deity Guan Yu.

Director Hung-Min Chen brings the aliens to Earth after a rash of near-Biblical phenomena (time runs backwards, gravity is broken). Once on Earth, the aliens terrorize both city and countryside until a sculptor working on a likeness of Guan Yu decides to ask the god for assistance. One burst of low-tech visual effects later, and a massive Guan Yu, bedecked in period military garb, shows up to spoil the alien's plans (read: bloodless dismemberment and crushing). For classic kaiju and mythology fans, these sequences may feel like your most fervent movie fantasies brought to lunatic life.

A*P*E features some truly preposterous fight scenes

Let's be honest. The 3D South Korean-American co-production A*P*E is a terrible film. It features, among other insane sights, a goofy, matted rug of a big ape that staggers around like it's on the tail end of a bender, flips off the South Korean army, and attempts to forge a romantic connection with Growing Pains' Joanna Kerns. That, in and of itself, is ridiculous, but really no better or worse than anything you'd see in half a dozen other truly awful giant monster movies. But A*P*E* — which was directed by American filmmaker Paul Leder — does feature two astonishing monster fights during its brief running time.

Granted, the "astonishing" part isn't due to any technical aptitude or quality special effects, but it's more because they're so bald-faced in their utter disregard for anything resembling excitement, tension, or energy. The second and lesser battle pits the A*P*E –- which is named, conveniently enough, Ape -– against a "giant" snake so lethargic that Leder has to throw it at the camera to not only remind viewers that they're watching a 3D movie but convince them that the serpent is real and capable of movement (even though it doesn't move).

The real money match is between Ape and a giant shark, and it was undoubtedly intended to double down on the film's exploitation quotient by tagging both the Dino De Laurentiis version of King Kong and Jaws. The fight itself is brief but disturbing, as the shark appears to be not only real but also either dead or in the process of passing away, given its limp and pallid appearance. Ape wins that match, but it's no point of pride.

Fairy and the Devil is four amazing creature features in one

This one requires a bit of explanation, but stick with it because the payoff is worth the effort. Fairy and the Devil is a Taiwanese fantasy-adventure from 1982 that's earned a devoted following for several outrageous scenes involving brawling giant monsters. However, dedicated sleuths like Die, Danger, Die, Die, Kill! and Maser Patrol have determined that these scenes –- featuring two flying dragons, a red-haired monster in battle armor, a white ape that grows huge to fight the ginger beast, and a humanoid sea creature –- may have been culled from several other Taiwanese fantasy films.

Chief among these is Tsu Hong Wu, a 1971 historical epic (in both scale and length), also known as The Founding of Ming Dynasty, and the apparent source of at least one dragon, the white monkey, and the red-headed monster. The devil-faced sea creature appears from Monster from the Sea, while the dragon featured in aerial dogfights with another beast is from Sea Gods and Ghosts (which also features the ape and red-haired monster fight). What's interesting to note is that all four films are largely action-dramas with occasional forays into martial arts and/or monsters, so one may assume that the enterprising producer of Fairy and the Devil thought that featuring all these scenes in a single film would be a home run. He or she wasn't wrong, and for those willing to dig into the sources of these scenes, they'll be rewarded with some mind-bending monster action.

Big Man Japan focuses on the freaky side of fighting monsters

The loser-as-superhero trope has been explored in several films –- most notably in Will Smith's Hancock and memorably as Chris Hemsworth's "Fat Thor" in Avengers: Endgame –- but none have gone so deeply into bizarre territory as the 2007 Japanese comedy-fantasy Big Man Japan, one of the weirdest monster movies of all-time.

Writer-director Hitoshi Matsumoto puts a wry spin on the genre via the mockumentary format, which focuses on the decidedly unremarkable Masaru Daisato (played by Matsumoto), the latest in a long family line of heroes called to protect Japan against a seemingly ceaseless monster invasion. Matsumoto does well at skewering the heroic side of the superhero life, which, for Daisatso, is not only unpleasant (he has to electrify himself in order to achieve kaiju size) but also messy, painful, and regarded by his fellow citizens as something of a nuisance.

Adding insult to injury is the parade of monsters he has to face — a head attached to a foot that bounces and yells incessantly, a grumpy female monster and her immature, excitable suitor, and a furry torso with a single eye in a very personal area. The fights are really secondary to the picture. If anything, the movie's most enjoyable element is how the ridiculous personalities of the creatures provoke Matsumoto's Big Man to battle them. If Ultraman was played as a disgruntled traffic cop, it might resemble Big Man Japan.

Monster X Strikes Back is a knowing kaiju spoof

Japanese writer-director Minoru Kawasaki specializes in broad lampoons of kajiu and tokusatu entertainment, with an emphasis on the more ridiculous creations that populate those projects. His 2004 feature The Calamari Wrestler concerns a grappler whose ring career is imperiled when he turns into a giant squid, while Monster SeaFood Wars from 2020 concerns a special team of soldiers assembled to battle what's essentially a malevolent fisherman's platter.

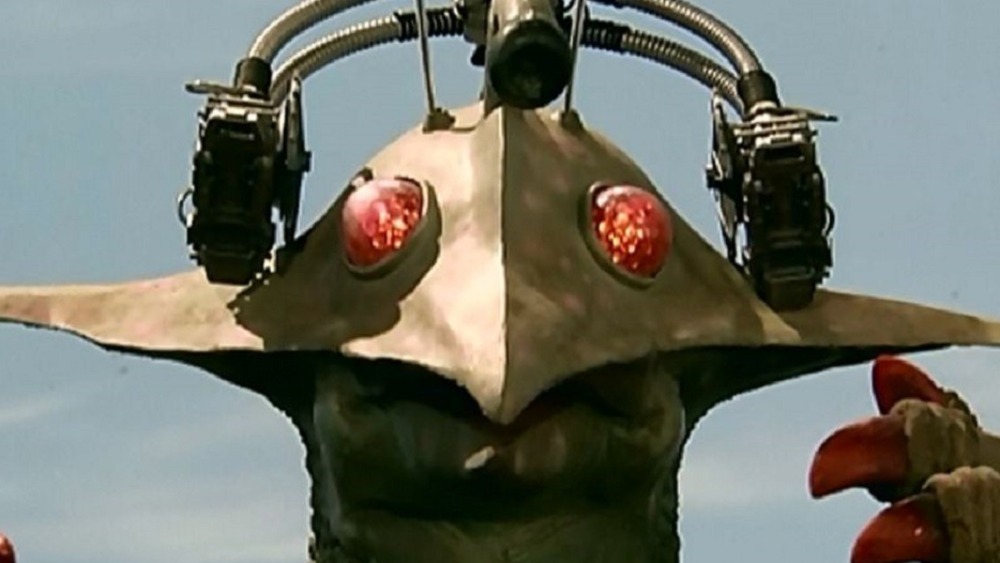

Between these efforts was his clever 2008 film Monster X Strikes Back: Attack the G8 Summit, which pokes fun at world politics and ineffective leaders while also spoofing two lesser-known giant creatures from the '60s. Monster X is actually Guilala, the extraterrestrial bird-reptile from 1967's The X from Outer Space, while its opponent, the multi-armed Take-Majin (voiced by Japanese cult actor/filmmaker "Beat" Takeshi Kitano) is a broad take on Daimajin, the avenging stone statue featured in three 1966 films from Gamera's home studio, Daiei. Their face-off is again played largely for laughs, but Kawasaki knows the right amount of explosions, tail-lashings, and left-field surprises (like Take-Majin's inventive ways of stopping a nuclear missile's progress) to keep giant monster fans both happy and amused.