The Weirdest Movie Monsters In Fantasy Films

When it comes to monsters in science fiction and fantasy films, they seem to break down along lines that echo the title of a great Italian Western — the good, the bad, and the ugly. In regards to the good, genre fans might pick creatures like the Balrog and the Witch-king of Angmar from the Lord of the Rings trilogy, while the Scorpion King from The Mummy Returns could be a solid candidate for both the bad and the ugly.

However, there are some fantasy and sci-fi creatures that fall into a fourth category — neither exceptional nor terrible but incredibly weird in terms of design, origin, and behavior. Unique, original, offbeat, implausible, and just plain odd, these beasts stand out because, for better or worse, there just isn't anything else like them in the vast menagerie of movie monsters. And if you want to see some of these critters up and close and personal, the following are vintage and modern movies featuring an array of curious creatures and bizarre beasts from the United States, Mexico, Japan, and other points on the globe. No passport required.

Warning — there are spoilers below.

The Crawling Eye is a movie monster that's weird and gross

Consider the eyeball. It's an organ of crucial importance ... but it's also a little gross. It's soft and filled with all kinds of fluids, and it hurts a lot if you stick it with a foreign object. So does it stand to reason that moviegoers might be paralyzed with fear by the thought of a giant, rampaging eyeball? The Crawling Eye, a 1958 British science fiction feature (also known as The Trollenberg Terror), certainly believed they might. And for a considerable portion of its running time, the film –- adapted from a popular TV serial by frequent Hammer Films scribe Jimmy Sangster -– does manage to raise some chills with the gruesome murder of hikers found with missing heads, as well as a strange radioactive cloud spotted in the Swiss mountains.

But much of the suspense is dissipated once a visiting American (Forrest Tucker) susses out what's inside the cloud — huge, blob-like aliens that come equipped with one enormous, glaring eye and a mass of probing tentacles. Admittedly, the monsters look like rubber novelties, much to the displeasure of its designer, special effects creator Les Bowie, who later shared an Oscar for Superman. But you have to admire the sheer wacko chutzpah of a enormous extraterrestrial eyeball, which has undoubtedly endeared the film to the Mystery Science Theater 3000 faithful, as well as fans like Stephen King, who made a Crawling Eye-like creature one of the final forms of the interstellar menace in his novel, It.

From Hell It Came ... or maybe the garden store

Special effects creator Paul Blaisdell was responsible for some of the most unusual looking monsters and aliens from low-budget horror and science fiction in the 1950s. His handiwork, produced quickly and with scant funding, includes the triangular Venusian in Roger Corman's It Conquered the World and the proto-Xenomorph in It! The Terror from Beyond Space. All of Blaisdell's monsters look like they're sprung whole from a child's drawings (or nightmares), but Tabonga, the demonic walking tree in 1957's From Hell It Came, suggests that the child might've had one too many sips of cough syrup before bedtime.

When a South Seas prince is wrongly sentenced to death for murder, his body is then buried and abandoned in a hollow tree trunk. The combination of bad juju and radiation from tests conducted by American scientists animates the trunk, which sprouts legs and the meanest face this side of the apple trees in The Wizard of Oz, and then it slowly and stiffly pursues its victims. There's nothing inherently odd about a monster tree –- malevolent magnolias were featured in The Evil Dead and Poltergeist –- but one that struggles to stomp after its prey while wearing the stiffest face this side of a drugstore Halloween mask is a whole different kind of forest.

There are four freaky aliens aboard The Ship of Monsters

In the 1960 Mexican-made The Ship of Monsters, Beta and Gamma, two glamorous visitors from Venus, land in Mexico for the purposes of collecting male specimens in order to repopulate their war-torn planet. Cowboy Eulalio "Piporro" Gonzalez soon becomes their quarry and their undoing, as his bravado and way with a song (several, actually) captures Beta's alien heart, which drives a wedge between the two space travelers. However, Beta is soon revealed to be a space vampire, and she releases their collection of captured creatures for world-wrecking purposes.

The monster rally is the element that transforms director Rogelio A. Gonzalez's film from a good-natured mix of pulp thrills and Western comedy into a hallucinatory experience. Gamma and Beta's menagerie seems culled from the fevered imagination of a '50s-era elementary schooler with a jones for pulp sci-fi and horror and a limitless supply of sugar. There's a tiny, bug-eyed alien with an exposed brain, a grunting, bat-eared cyclops, a trembling spider thing, and a skeleton with a constantly flapping jaw. Budget and time constraints in Mexican genre filmmaking often produced some oddities –- e.g. the dirty rubber sheet meant to be an alien blob in Santo vs. the Killers from Other Worlds –- but the calamitous quartet in Ship of Monsters are unquestionably the most feverishly freaky exports from science fiction south of the border.

Please don't eat the Matango

While Toho Studios earned its enduring fanbase on the strength of its giant monsters, most notably their Godzilla movies, they also dabbled in more down-to-earth creatures, including 1958's The H-Man and 1960's The Human Vapor. But its most memorable and disturbing human-sized creation was unquestionably 1963's Matango, which English-language viewers may have caught on late-night television under a more spoilerish title: Attack of the Mushroom People.

And that's exactly what the passengers of a shipwrecked yacht encounter on a remote, fog-shrouded island, where its abundant fungi spur terrible mutations in anyone foolish enough to eat it. The transition from human to matango is particularly nightmarish. The victims are gradually subsumed by a slow-spreading fungus that ultimately transforms them into huge, ambulatory mushrooms, complete with fungal caps.

Matango really shouldn't work. It is, after all, a movie about people turning into toadstools. But the hideous creature design (overseen by the legendary Eiji Tsuburaya), an appropriately psychedelic landscape of the island (by special effects art director Akira Watanabe, among others), and an overall atmosphere of claustrophobia and paranoia from veteran Toho director Ishiro Honda (Godzilla) mesh well to produce one of the most unnerving and disorienting Japanese fantasy films of the 1960s.

Frankenstein and the Gargantuas: Toho's first family of fright

Toho Studios also counted more than a few bizarre giant monsters in its kaiju menagerie, but few had as complicated and strange a backstory as the Frankenstein "family." The saga begins in 1965's Frankenstein Conquers the World (aka Frankenstein vs. Baragon), in which the Nazis transport the heart of the Frankenstein monster to Imperial Japan during World II. Radiation from the bombing at Hiroshima causes the heart to regenerate into a sort of feral teenager that soon grows to several meters in height and takes on a dinosaur named Baragon that also happens to be running amuck before both are swallowed up in an earthquake.

Based loosely on an unproduced treatment by Willis O'Brien, who created the stop-motion effects for the original King Kong, Frankenstein generated a sort-of sequel in 1966's The War of the Gargantuas, which in the original Japanese release posited the notion that cells from the '65 Frankenstein somehow regenerated into two giant apelike creatures — the gentle brown monster, Sanda, and Gaira, a more aggressive green beast with an appetite for humans. Gaira's proclivities put him on the wrong side of his brown brother, and the pair wage a full-tilt battle before they, like their parent, are done in by a natural disaster (an undersea volcano).

Most American viewers were unaware of the connection between the two films due to co-producer Henry Saperstein, who replaced any reference to "Frankenstein" with "Gargantua" in the English dub. Despite its bizarro premise, Gargantuas is a favorite of classic kaiju fans, including Brad Pitt, who waxed rhapsodic about it on the 2012 Oscar telecast.

Night of the Lepus proves bunnies aren't scary

In the right hands, a seemingly innocent or harmless object can be quite disturbing. Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds and the Child's Play and Annabelle franchises are perfect examples. And in the wrong hands, you get something like 1972's Night of the Lepus, which attempts to pass off sweet, fluffy bunnies as colossal man-killing machines. If that sounds like a tall order, you're right.

Tasked with convincing audiences that experimental hormones have made desert rabbits grow to the size of Volkswagens, director William F. Claxton and producer A.C. Lyles -– both veterans of the Western genre, but with little experience in horror or science fiction — used miniature sets, slow-motion effects, and monster noises to make their stunt bunnies seem menacing. And according to some sources, human actors in rabbit suits were also employed to make the attack scenes seem more alarming.

But unlike rats, birds, or reptiles, there's nothing inherently terrifying about rabbits, no matter how much ketchup one splashes on them to suggest a gory repast. Using plump, perky domesticated rabbits instead of marginally less adorable wild rabbits only further detracted from the scare factor. MGM attempted to mitigate the impending disaster by eliminating any suggestion of rabbits from their press material -– the trailer refers to "mutants" –- but once the movie unspooled, the fuzzy, lop-eared truth was out.

The Godmonster of Indian Flats is a mutant sheep

An acclaimed artist whose work has been showcased in museums across America, the late Fredric Hobbs also tried his hand at filmmaking, which yielded four very strange experimental films, including 1973's Godmonster of Indian Flats, a creature feature/Western/comedy/ecological statement. Hobbs also constructed the titular beast, a sheep embryo exposed to fumes from a Nevada mine that grows into an awkward, bipedal tangle of wool and mutated limbs. The end result, while absurd by movie standards, does reflect Hobbs' signature style, a mix of natural and found objects and modern primitive sculpture, while also provoking a mix of laughter and pity for its ungainly appearance.

For much of Godmonster's rambling and disjointed running time, Hobbs uses the monster as a shambling metaphor for nature's revenge against all manner of social ills, including industrial exploitation and scientific misappropriation. It also manages to carry out a few traditional monster duties, though again, its Muppet-in-the-spin-cycle look doesn't generate much terror beyond breaking up a tea party of little girls, who run in shrieking terror from the thing wobbling towards them.

Meet Mr. Vampire, one of China's jiangshi

Most world cultures have a vampire in their mythology, but few are as unusual as the Chinese variant, known as "jiangshi." Though they share some similar traits with Western vampires -– pale or green skin, a mouthful of sharp teeth, a dislike for sunlight –- jiangshi don't drink blood. Instead, they feed on their victim's life force, or "qi'." And while Western vampires can adopt several modes of transportation to pursue their prey (floating, turning into mist, transforming into animals, etc.), jiangshi can only hop with arms outstretched, due to the stiffness caused by rigor mortis.

That particular trait has made the jiangshi a popular focus for horror comedies like martial arts great Sammo Hung's Encounters of the Spooky Kind in 1980 and Mr. Vampire, which Hung produced in 1985. The latter — which featured actor and stunt coordinator Lam Ching-ying, the man who assisted Bruce Lee in choreographing the fight sequences for his seminal martial arts films -– proved enormously popular throughout Asia, and it led to numerous sequels and spinoffs in the 1980s and 1990s. Like many movie monsters, jiangshi have also transitioned from grown-up terror to characters in children's entertainment, including Kung Fu Panda: Legend of Awesomeness, and as playable characters in numerous video games.

Hell Comes to Frogtown, warts and all

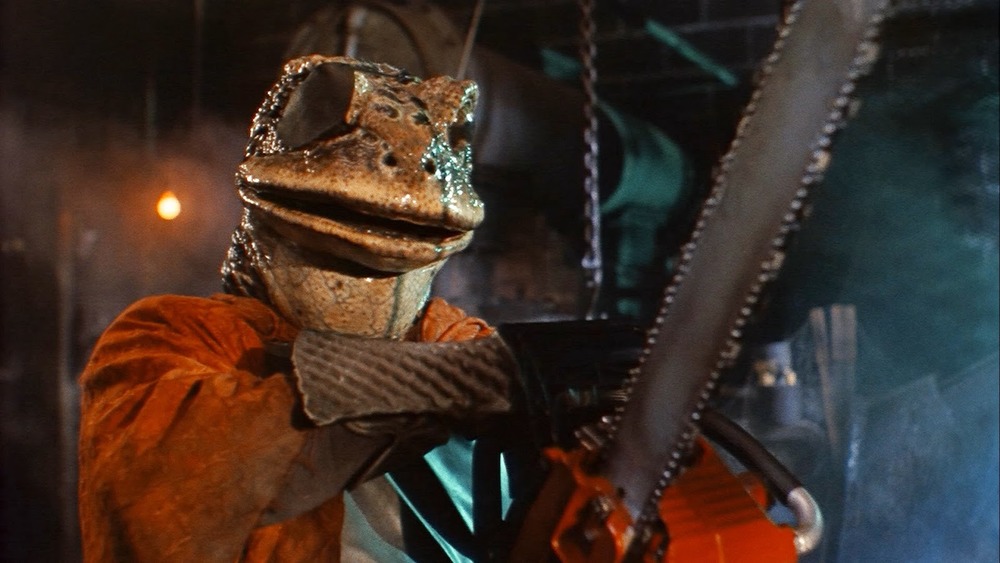

When the apocalypse finally hits, you should know that survivors will be divided into three groups — beefy he-men like Roddy Piper, industrious women, and giant, humanoid frogs with entirely inappropriate designs on that second group. Such is the breakdown for humanity in Donald G. Jackson and R.J. Kizer's (sticky) tongue-in-cheek, guilty pleasure sci-fi flick, Hell Comes to Frogtown.

In this 1988 film's post-apocalypse wasteland, it's not water or oil that's in demand but fertile men like Piper, whose wanderings are interrupted by Sandahl Bergman and a crew of military scientists with designs on repopulating the world. But when the frog mutants make off with the last remaining women, Piper is pressed into chew-bubble-gum-and-kick-butt mode in order to save humanity. An amusing spoof of post-nuke movie tropes, Frogtown also delivers a knowing nod to unlikely (and ungainly) science fiction monsters in its frog mutants, whose hormonal overdrive and low-wattage IQ evoke the lascivious monsters of pulp fiction and Depression Era serials.

Big Man in Japan fights big monsters with big problems

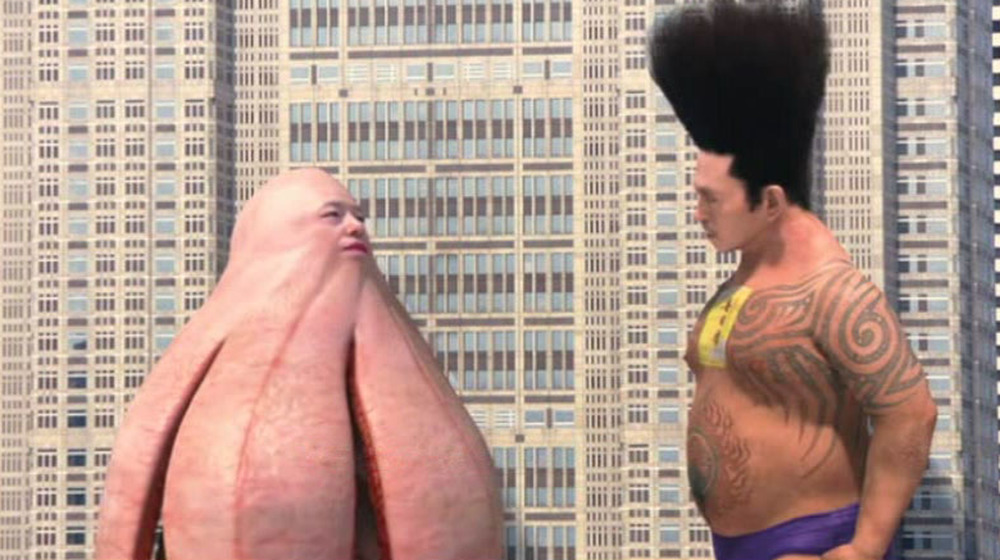

Giant monsters get the mockumentary treatment in Japanese comedian Hitoshi Matsumoto's very funny 2007 film, Big Man Japan. Matsumoto also stars in the title role, the latest in a long line of monster fighters assigned to protect Japan from its ceaseless hordes of invading monsters. When jolted with electricity, Matsumoto grows to skyscraper height (with appropriately gravity-defying hair) and tangles with an increasingly bizarre assortment of rampaging kaiju.

Much of the humor in Big Man Japan derives from its spin on the monster-fighting business. Rather than being heroic, punching out kaiju is shown as thankless and routine, and its heroes are more ultra-schlub than Ultraman (Matsumoto also pokes fun at Eiji Tsuburaya's alien-fighting family with the Super Justice brood, a gaggle of mean-spirited bullies). Its most effective gags come with its parade of monsters, which take the out-there creature design from decades of Japanese films and TV shows to the conceivable limit. The Leaping Monster is an agitated leg topped with a grinning human head, while the Evil Stare Monster sports a glaring eyeball on the end of a very personal appendage. Bodily functions are recurring gags for several monsters, including the Strangling Monster, which lays eggs with abandon in ruined cities, while the Male and Female Stink Monsters ... well, those two have issues.

The Hollowgasts want your eyes

The primary antagonists in both Ransom Riggs' 2011 book Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children and the 2016 film adaptation by Tim Burton, the Hollowgasts are pure nightmare fuel. They were once a group of scientists with exceptional powers –- known as "Peculiars" –- who attempted to gain immortality through the use of a time loop. The experiment failed, resulting in a devastating explosion and the transformation of the Peculiars into Hollowgasts –- shadow figures visible only to certain Peculiars, like the book and film's hero, Jacob Portman.

Their invisibility is a good thing because the true form of a Hollowgast is pretty horrible. It's a humanoid figure with a Lovecraftian tangle of tentacles sprouting from its mouth. The tentacles allow them to consume the souls of their chosen prey –- other Peculiars –- which grants the Hollowgasts a corporeal form known as a Wight, which looks more human with one unpleasant difference ... white eyeballs without pupils. The film version of Miss Peregrine ups the ugly in its depiction of the Hollowgasts, which are seen as tall, slim, and faceless monsters that bear more than a passing resemblance to creepypasta favorite Slenderman. The movie Hollowgasts also gain extra gruesome points for dining on eyeballs instead of souls.

Two heads are better than one with Jack the Giant Slayer's monstrous villain

If a giant humanoid is scary, shouldn't a two-headed giant be twice as terrifying? Well, if you're General Fallon, the leader of an army of man-eating giants in Bryan Singer's Jack the Giant Slayer, the answer is yes and no.

Fallon, whose voice is courtesy of the great Bill Nighy, certainly meets the criteria for frightening movie monster — enormous, warlike, and determined to conquer (and, most likely, eat) the whole of humanity. But Fallon is also outfitted with a second, smaller head that sprouts from his shoulder and appears to serve as Fallon's hype man, comic relief, and nagging conscience, all the while spewing volumes of gibberish (provided by John Kassir, the voice of the Crypt-Keeper on the HBO Tales from the Crypt series).

Fallon's little head (so to speak) is so animated and off-the-wall that it ultimately detracts from the big head's diabolical villainy and makes them more of a comedy team specializing in nagging humor. There is, however, a precedent for Fallon's twin heads. His design appears to be a nod to the 1962 Jack the Giant Killer, which features both single- and two-headed giants created by the Oscar-winning Project Unlimited, Inc., which designed special effects for The Time Machine and the Outer Limits TV series, among many other projects.