Why Big Fish Is Tim Burton's Best Film

When people think of Tim Burton, they think of his cartoonish depictions of the macabre. Yep, even when they think of Pee-wee's Big Adventure – remember Large Marge? Few directors have been so deeply associated with a particular aesthetic as Burton, so when he decides to change things up, it's automatically going to make waves.

One such mold-breaking Burton movie is 1994's Ed Wood. But even then, there is an artifice to Wood's legend that matches Burton's vibe. Making a movie about Ed Wood didn't challenge Burton's approach so much as take it in a specific direction. Likewise, when Burton took on 2001's Planet of the Apes, he seemingly tried to do what he did with the first two Batman movies, squeezing the primary components into his peculiar aesthetic. Unlike Batman and Batman Returns, however, it didn't work. Fortunately for movie fans, Burton seems to have seen this failure as a sign guiding him to make a drastic change.

2003's Big Fish doesn't eschew Burton's "isms," but it does compartmentalize them. Thus, the film ends up being a great tribute to storytelling: Instead of just glorifying fantasies and whimsical visuals, it gives them real-world consequences and weight — something a Tim Burton movie hadn't yet fully achieved at that point in his career. This is what makes Big Fish Tim Burton's best film, among many other factors. Allow us to convince you.

Big Fish is about fathers and sons

Tim Burton has parent issues. From the murder of the Waynes to the passing of Edward Scissorhands' inventor to Ichabod Crane's mother being skewered in an iron maiden, the sins of the parents being visited upon their children is an ever-present point of his films. However, in nearly all of these examples, there is a distance between the two parties filled by magic or the macabre. When death comes, it does so in dramatic fashion.

Burton doesn't completely reject that approach in Big Fish, but he certainly opens up the narrative to a new vulnerability. Will Bloom (Billy Crudup) needs to spend time with his dying father, Edward (Albert Finney). Their relationship is difficult, as Edward forever recounts their family history as a fable-filled journey of nonsense, while Will just wants his dad to get real with him — or a least not embarrass him with more tall tales.

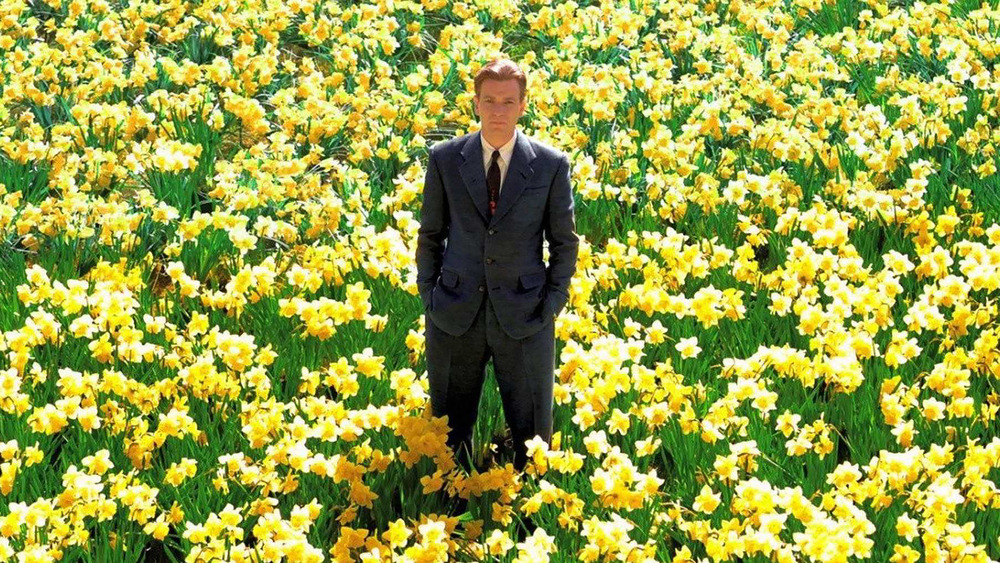

In between these raw moments, the audience goes on a journey with a younger version of Edward, played by Ewan McGregor, into the depths of his fantastic life. There is a truth every child must bear, whether they like it or not: They will never really know their parents as people. Big Fish focuses on those mysteries parents can never fully impart to their kids, no matter how hard they may try.

Big Fish's balance of fact and fiction

The central theme of Big Fish is the difficult task of understanding family history. A story about this topic doesn't have to be dark and gritty: More often than not, our histories are plain, unremarkable things. There's a lot of waking up and going to bed, with a few sandwiches in between. It is this basic, unremarkable side that Will Bloom wants from his father, but cannot have.

Edward is a storyteller and lives to embellish even his most banal moments a magical flourish. Will resents this opaque approach, having lived with these stories all his life, which furthers his estrangement from his dad. It is only when the most plain, unadorned reality of Edward's impending death intrudes that Will allows himself to let Edward back into his life.

In a heartbreaking scene, Edward, who has had a stroke, knows his time is short. He asks his son to tell him how it all will end. For Will, his act of compassion is to couch Edward's final moments in the language and stories he has long disdained. It is not until Edward's funeral that Will finally gets to meet the analogues of Edward's mysterious characters. They're more plain and unremarkable than he described, but still real. In his own way, Edward was honoring his friends and acquaintances by imbuing them with a more mystical side than reality allowed them.

A new kind of source material

While Tim Burton had already proven to be adept at working with established characters and franchises, Big Fish was his first true adaptation of a preexisting story: Daniel Wallace's 1998 novel of the same name. The book has a weight to it that is absent from Burton's pre-Big Fish films. While Burton would eventually inject a large amount of his filmmaking personality into Big Fish, the project put the director inside a unique new box. That limitation is one of the film's greatest strengths, as it forced Burton to stretch his wings within the realistic, dramatic sections of the film. As far as cinematic adaptations of books go, it's one of the best.

In a 2015 interview, Wallace reflected on the movie and what it meant to him to finally be published, and then to have his book adapted for the silver screen. The sweep of it all was hard to take in: "I didn't 'grasp' it so much as I decided just to enjoy it," he reflected. "And that's what I did."

A long partnership with John August

Tim Burton is known for retaining a core team of co-creators, including composer Danny Elfman, actor Helena Bonham Carter, and editor Chris Lebenzon. With Big Fish, Burton added screenwriter John August to his troupe — but it was more a case of happenstance than strategy. August was the one who got the ball rolling on a Big Fish movie, out of his own interest. Steven Spielberg was attached to direct it at one point, but ultimately stepped back.

The project appealed to Burton, as he himself was dealing with the grieving process prior to signing on as director of Big Fish. His father died in 2000, and his mother passed in 2002. The weight of this story, about a child coming to grips with the loss of a parent, wasn't initiated by him — instead, it sought him out.

The collaboration with August proved to be a winning combo. Burton would go on to work with August four more times, on Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Corpse Bride, Dark Shadows, and Frankenweenie. August also contributed to the book for the Big Fish Broadway musical, wrote and directed the film The Nines, and created the Arlo Finch young adult novel series.

Big Fish's cast goes beyond the Burton standbys

Tim Burton is known for his long relationships with trusted collaborators. The pairing of Burton and Johnny Depp is as cemented as Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro. Similarly, Burton's bond with composer Danny Elfman is as strong as Steven Spielberg's with John Williams.

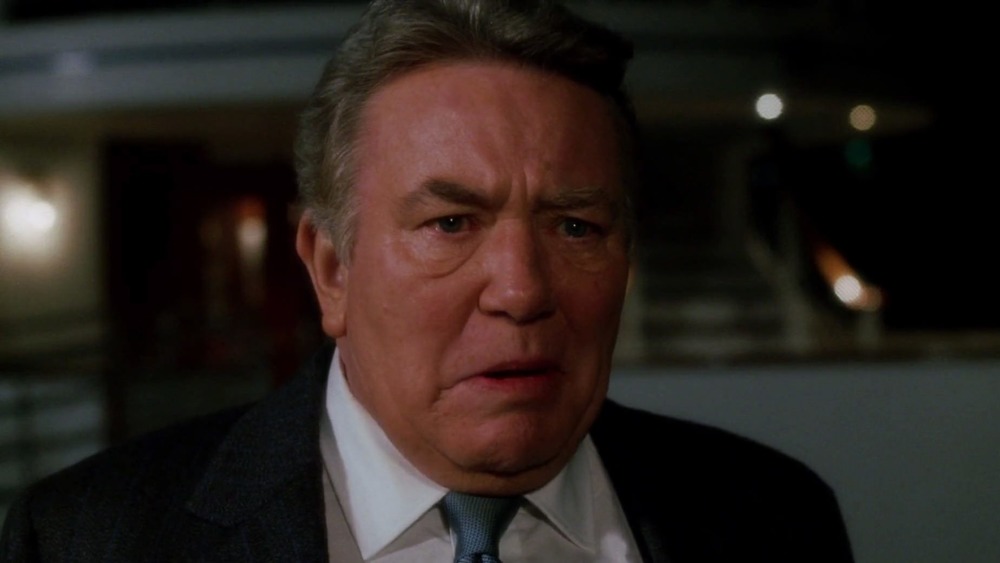

As such, there were expectations of who would be in the Big Fish cast. Helena Bonham Carter shows up, as does Missi Pyle and Danny DeVito. These Burton standbys all do remarkable work in the film. However, Burton's unexpected choices are what truly make the movie. Having Albert Finney play the gregarious, storytelling Edward as a man in his waning days is especially perfect casting. The same holds true for Billy Crudup as his son Will. The film's major coup was casting Jessica Lange, an actor with the chops to stand between Finney and Crudup in the most tense scenes of the movie. Her desire to have some sort of reconciliation occur between her husband and son before it is too late is the beating heart of the story.

Add in the likes of Alison Lohman, Ewan McGregor, Steve Buscemi, actor-musician Loudon Wainwright III, and even Miley Cyrus in a small role, and you've got cinematic magic. Big Fish augmented Burton's typical stable of actors and is all the better for it.

Tim Burton spends some time in the real world

Since Big Fish, Tim Burton has dipped his toes into more realistic waters, but only briefly. His gruesome 2007 adaptation of Sweeney Todd is very much within his comfort zone, for example, as is 2010's Alice in Wonderland. His 2014 film Big Eyes, about artist Margaret Keane, made some waves, thanks to the performances of its leads, Amy Adams and Christoph Waltz. But mostly, Burton has stuck to his twisted, wrought-iron guns in terms of storytelling.

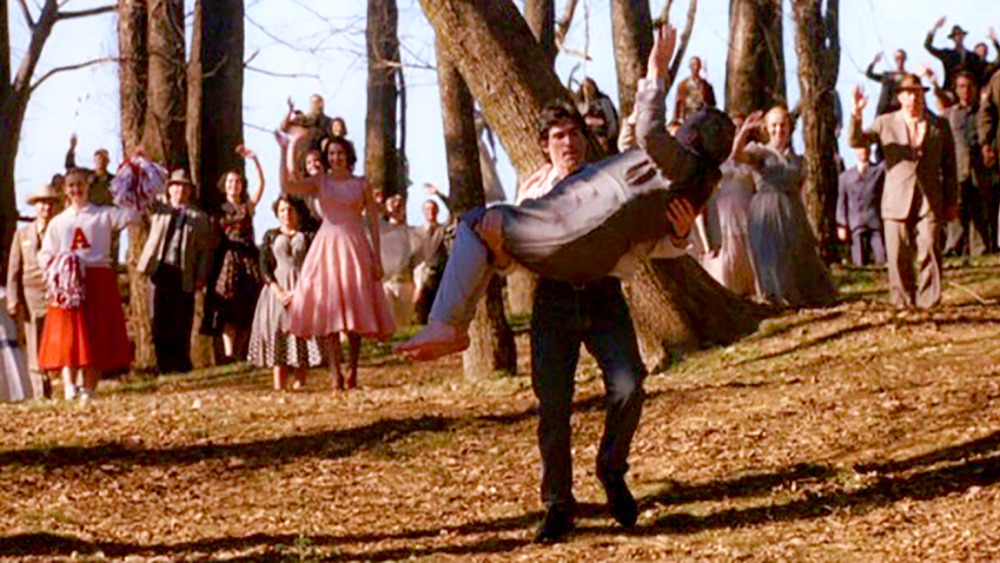

Burton sticking to what consistently works for him isn't a bad thing. But in departing from it, Big Fish is made all the more remarkable. Yes, there are the candy-colored Odyssey-lite vignettes seen through the eyes of young Edward Bloom, which play directly into Burton's established strengths. But the film truly impresses when it goes beyond these boundaries. In scenes that focus on Edward Bloom, his fed-up son, and Sandra, the wife and mom forced to play referee, one gets to see a whole other side of Tim Burton's abilities.

One has to wonder if part of the goodwill Big Fish has garnered comes primarily out of seeing Burton be this bold without the usual training wheels on. Given how rarely he's stepped back into that real-world setting since, we probably won't see much more like it.

Albert Finney and Billy Crudup

The soul of Big Fish resides in the difficult relationship between Edward and Will. While the storybook tales Edward tells comprise the larger part of the film, it is the glimpses of Edward and his son that give the narrative its weight, and, in an odd way, might give it a biographical edge.

This is a story we typically see with the roles reversed: The artist (perhaps a filmmaker) has their storytelling inclinations derided by a parent who wishes the child would just get a "real" job. Switching these roles around provides Big Fish with a unique and engaging set-up. We root for Edward and his flamboyant story, but we also side with Will's occasional embarrassment and continual frustration. He simply wants a real understanding of his father's life without the Disneyland trappings.

This is what makes casting Finney and Crudup as Edward and Will so pivotal. Finney makes Edward a gregarious raconteur, not a kook. Crudup makes Will recognizable as someone with a hole in his life who feels resentment that his father withholds information that might fill it. He's wounded, but he is not a jerk, nor ungrateful. In the hands of lesser actors — or a director unwilling to commit fully — it could all reduce down to a sludge of movie-of-the-week melodrama. Instead, Finney and Crudup make it matter.

Big Fish and life after awards season

Big Fish earned $123 million worldwide, a major success given its $70 million budget. Generally, the movie received positive reviews. Several critics, however, were indifferent to the film, praising its look but damning its whimsy. This viewpoint seemed to carry over to the Oscars, with only Danny Elfman's score getting a nomination. It did not win. The film did garner BAFTA and Golden Globe nominations for multiple key categories, including Best Director, Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Albert Finney, and Best Adapted Screenplay for John August. However, it won none of these.

Yet time has been good to Big Fish. When enjoyed years after its debut (we can only imagine the modern ad copy shouting, "It's Tim Burton's film for grown-ups!"), there is a tenderness and sense of purpose to the movie made apparent within the scope of Burton's filmography. Given that he directed it so closely to the passing of both his parents, the sentimentality shows through — and that is a good thing. The story was not initiated by him, but it landed in his life when he was at his most vulnerable, and it works. Burton is seldom a critic's darling, with many negatively citing his dominant style and inclinations. But Big Fish manages to get beneath the flash of Burton's approach and move the genuine heart at the center of the story.