Small Details You Missed In Mank

This content was paid for by Netflix and created by Looper.

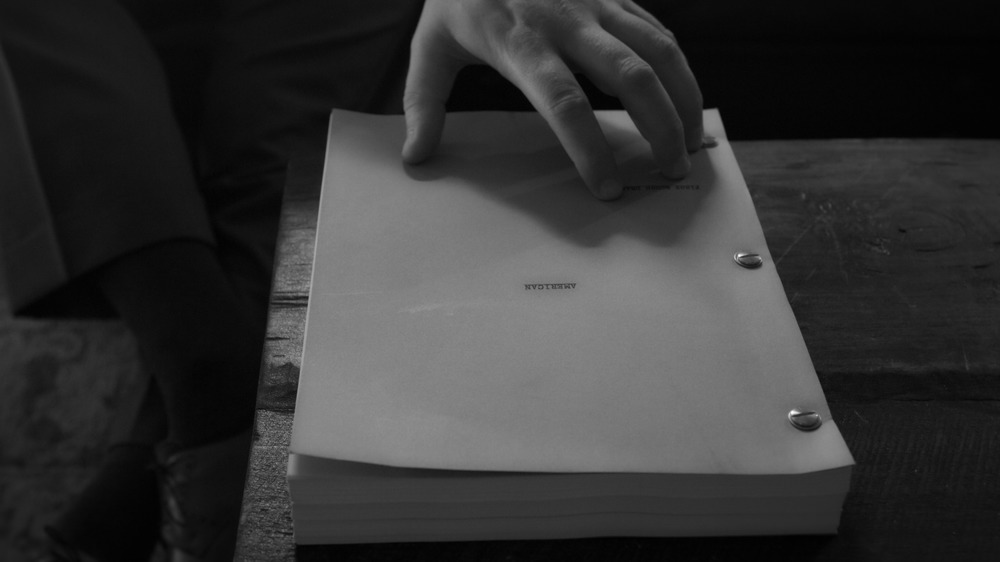

Mank isn't just a movie about Hollywood screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz. And it's not just about the long, winding road that led him to writing Citizen Kane, the Orson Welles film that's considered one of the very best ever made. It's also a harrowing look at how the people in charge wield their power, and how the people under their influence — willingly or otherwise — deal with them. It's a comedy, a tragedy, and a daring technical experiment. It's a showcase for top-tier actors like Gary Oldman, Amanda Seyfried, Lily Collins, and Charles Dance, as well as director David Fincher, who hasn't directed a feature film for six years.

Most of all, though, Mank is a love letter to Golden Age Hollywood. Not only does Mank look and sound like a movie from the '30s, but Fincher's affection for both Citizen Kane and its peers seeps through every frame. It's subtle, but Mank is loaded with small details that film buffs are all but guaranteed to go crazy for.

But you don't need to be familiar with the source material to enjoy Mank. Even if you've never heard of Citizen Kane, there's plenty here to enjoy. Still, if you don't have a film degree, there are some small details in the movie that you probably missed. Here are just a few of 'em.

Like Fincher, like Fincher

Director David Fincher, the man behind The Social Network, Fight Club, Seven, Zodiac, and Mindhunter, isn't the only Fincher in Mank's credits. The screenplay for the movie was written by one Jack Fincher, and yes, there absolutely is a relation: Jack was David's father.

As David tells it, his old man was a huge movie buff, and Citizen Kane was his favorite movie. David told Vulture that Jack started teaching him about filmmaking when he was only seven. He watched Citizen Kane by the time he was 12. After Jack, an accomplished journalist, retired, he decided to set his sights on writing a screenplay. David, who was just about to direct his first feature, was the one who suggested that Jack write about Herman J. Mankiewicz and the development of Orson Welles' signature film.

Jack worked on Mank throughout the '90s, with David planning to direct as early as 1997, after he finished The Game. Unfortunately, things didn't fall into place. Studios weren't keen on making black-and-white period piece about a 50-year-old movie, and young David couldn't relate to the more mature perspective offered by Jack's script.

Sadly, Jack passed away in 2003, and Mank sat on the shelf for years and years. Thankfully, it didn't stay there. After finishing the second season of his TV show, Mindhunter, in 2019, Fincher decided to revisit his dad's old script — and the result is the director's first feature film in six long years.

So, they actually do make them like they used to

Mank doesn't just tell a story about 1930s Hollywood. It also looks and sounds like a movie from the 1930s, even though it's a decidedly modern product. That is, of course, by design. While you're watching, you'll immediately notice that the film features stark black-and-white photography that resembles the work of Citizen Kane cinematographer Gregg Toland. The acting eschews modern innovations in favor of a heightened, old-fashioned style that recalls the performances of Hollywood's golden age.

But that's really just the tip of the iceberg. Mank's attention to period detail goes much, much deeper. Unlike most modern blockbusters, Mank's sound was mixed in mono, giving it a retro feel. The dialogue and music were recorded using vintage equipment, adding an old-school hiss that classic movie fans will find very, very familiar. Musicians Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, who composed and performed Mank's score, used period-appropriate instruments, not the synthesizers they're known for.

Visually, the Mank crew did the same. While Mank was filmed digitally, the picture was intentionally degraded, robbing the picture of about two-thirds of its detail and making it look like a movie from the '30s. Scratches were added during post-production to give the impression that Mank had just been discovered in some long-lost archive. Fincher also made another addition to the film in the form of cigarette burns — i.e. the small marks in the upper right corner of the picture that let projectionists know when it's time to change reels — even though Mank was made to be shown digitally. Listen carefully, and you'll even hear a subtle pop when the "reels" change, just like you would in a vintage film.

And then, of course, there are the specific nods to Citizen Kane itself. While Fincher never gets too cute with his references, Mank's non-linear structure parallels Kane's. Not only that, but take a look at the scene where Mankiewicz stands in front of a huge fireplace, face dominating the frame, during his last visit to Hearst Castle. If you mistook that for a shot straight out of Citizen Kane, well, no one would blame you.

Ranch (set) dressing

In flashbacks, Mank travels to glamorous locations like Golden Age Hollywood and William Randolph Hearst's stately pleasure dome in San Simeon, but the present-day story takes place in a much more modest setting. In an effort to separate Herman Mankiewicz from his worst impulses, Orson Welles whisks the screenwriter away to the secluded — and, more importantly, dry — North Verde Ranch in Victorville, California, roughly an hour-and-a-half drive away from Los Angeles.

Visually, the setting looks both like it's been plucked straight out of the '40s and put in front of David Fincher's camera, and like an excellent place to write a screenplay without any distractions. There's a good reason for both. Kemper Campbell Ranch, where those scenes were filmed, has been in operation since the '20s, and has changed very little since then. It's also where the real-life Mankiewicz shacked up and wrote Citizen Kane. In other words, Mank was filmed in the same location where the actual events in the film took place, albeit 80 years earlier.

Throughout the '30s, the ranch was a popular vacation hideaway for Hollywood talent, and hosted showbusiness legends like John Wayne, Greta Garbo, and Groucho Marx. It was renamed the Kemper Campbell Ranch in 1943. And while it closed its doors to general visitors in 1976, it's still available for group rentals and film shoots.

If I hadn't been very rich, I might have been a really great man

Orson Welles isn't physically in Mank all that much, but his shadow looms large over the whole movie. After all, it's Welles who hires Mankiewicz off to write his script, and it's Welles — and his 60-day deadline — that Mank is working so hard to satisfy.

As such, Mank tosses out a few references to Welles pre-Hollywood career, and not just his big hits like his radio show, Mercury Theatre of the Air, his politically-charged production of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, or his infamous, panic-inducing adaptation of War of the Worlds. For example, at one point, Mankiewicz mentions Welles' "voodoo Macbeth." That's not just a gag. In 1936, just a couple of years before Hollywood came knocking, Welles put on an all-Black production of the Shakespearean tragedy, which premiered at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem.

The play was highly controversial. The production was funded by the federal government as part of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, using money that many felt could be better spent elsewhere. Black audiences accused Welles — who moved the play's setting from Scotland to Haiti — of caricature, and wondered why a Black director couldn't be involved. White critics, meanwhile, responded with the expected racism of the era. And yet, the lavish production was a huge hit, earning a standing ovation after its premiere for all 750 members of its cast and crew.

In addition, throughout Mank, Welles is working on another big Hollywood project, an adaptation of Joseph Conrad's novel Heart of Darkness. That was also a real project, although unlike Citizen Kane, it never made it to the big screen. Studio executives refused to pay for Welles' elaborate production, and balked at the experimental methods he wanted to use to make the movie. So, Welles gave up and made Citizen Kane instead. Yes, that's right: One of the most famous and influential movies ever made was originally little more than Welles' back-up plan.

Back to the Golden Age

Mank is a celebration of 1930s Hollywood, but it doesn't hit you over the head with its classic film references. Still, if you look carefully, you'll find quite a few — most of which are a little more subtle than Herman's constant gripes about The Wizard of Oz (which he co-wrote, although he's uncredited).

For example, when Charlie Lederer first shows up on the Paramount lot, you can see large posters for Love Among the Millionaires, a comedy starring original "it girl" Clara Bow (co-written by Herman Mankiewicz, by the way) and classic Gary Cooper western The Virginian hanging on the side of studio buildings. When Mankiewicz and his team pitch their creature feature to the Paramount brass, you can catch a few more: One-sheets for The Four Feathers (a war film directed by King Kong's Merian C. Cooper and starring that movie's damsel-in-distress, Fay Wray), the Burlesque adaptation The Dance of Life, and the Emil Jennings vehicle Betrayal all hang on the walls.

There are a number of references to Mankiewicz's career thrown into the movie, too. Herman's constant references to the Marx Brothers make more sense when you realize that he produced a number of their films, including Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, and Duck Soup. The Lon Cheney movie that Mankiewicz wrote is The Road to Mandalay, a film that's been lost to time — only an abridged, low-quality, 33-minute cut remains.

And yes, Mankiewicz really did write a movie about Nazis that Hollywood was too scared to produce. It was called The Mad Dog of Europe, and told a deeply satirical and eerily prescient story about the rise of a dictator named Adolf Mitler. In fact, Mankiewicz wrote the film all the way back in 1933, the same year that the Nazis' first concentration camp opened, and years before World War II began in earnest.

The writers behind the words

In the '30s, films were largely written by groups of people, not individuals (although not everyone who contributed got a credit), and Mankiewicz's writer's room at Paramount is made up of a number of Golden Age Hollywood heavyweights. Charles Lederer, Marion Davies' nephew, wrote classics like The Front Page, His Girl Friday, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and the original Ocean's 11. George Kaufman was better known for his stage work, but he did contribute to a number of screenplays, including the Marx Brothers' A Night at the Opera. Humorist S. J. Perelman is responsible for Around the World in 80 Days. Charles McArthur won an Oscar in 1936 for co-writing The Scoundrel with Ben Hecht, another member of the group.

Hecht himself is practically show business royalty, with six Academy Award nominations (and two wins) and classics like A Star Is Born, Stagecoach, and Notorious to his name. He's considered one of the very best writers of the era, and was the real-life recipient of the telegram that Mankiewicz sent to Lederer in the film: "Millions are to be grabbed out here, and your only competition is idiots."

Finally, there's Herman's brother Joseph, who ended up becoming an extremely accomplished filmmaker on his own. Not only did the younger Mankiewicz write close to 50 screenplays, but he produced the Jimmy Stewart classic The Philadelphia Story and won back-to-back directing and writing Oscars for A Letter to Three Wives and All About Eve, which remains a favorite to this day. He was also in the director's chair for the big-screen adaptation of Guys and Dolls and Elizabeth Taylor's Cleopatra, which was, at the time, the most expensive movie ever made.

Let them eat cake

While Herman Mankiewicz is Mank's star, movie star and William Randolf Hearst's mistress Marion Davies also gets a lot of attention. In Mank, her story comes to a head late in the film, when she departs MGM for Warner Bros. after MGM's hotshot producer Irving Thalberg refused to cast Davies as the lead in Marie Antionette. Later, at Hearst Castle, MGM head Louis B. Mayer complains about how the movie is turning out, assuring Davies — not entirely truthfully — that it would've been better if she had starred.

That's all true, but Marie Antionette actually intersects with Mank's various subplots a little more than the movie lets on. For one, it was the last movie that Thalberg made at MGM. For another, after passing on Davies, Thalberg cast his wife, Norma Shearer, in the lead role. That's why Mayer says that the Marie Antionette star should've taken a sabbatical to get over her grief. As Mank shows, Thalberg passed away shortly before production began. Finally, Mayer's dissatisfaction with the film — "You can't tell those stories without overhauling them for a modern audience," he complains — is only to be expected. Mayer and Thalberg often clashed over what types of movies to make. In fact, Mayer actually demoted Thalberg in 1933 during one of Thalberg's health scares and replaced him with David O. Selznick, who was much more into the crowd-pleasing spectacles Mayer preferred than Thalberg's more "literary" movies.

In addition, despite what Mank's L. B. Mayer would have you believe, audiences loved Marie Antionette, which earned four Oscar nominations. However, with a staggering $2.9 million budget, Marie Antionette was also one of the most expensive movies of the '30s. Despite its popularity, it failed to make a profit.