Movies Based On Board Games That Are Actually Good

When you're staying in, two of the most popular activity choices are movie nights and board game nights — so it makes sense that movies based on board games constitute one of the most popular genres of film.

Just kidding.

Movies based on board games are fairly few in number — while there are plenty of board games out there, it would be difficult to develop most of them, like Scrabble or Sorry, into a feature-length plot — and they rarely do well at the box office or in critical circles. A successful movie adaptation of a board game, then, is a pretty impressive feat, especially when you're not counting films that are so bad that they're good. There are many aspects that make this endeavor difficult, and one that few filmmakers dare to approach. The result is a sparse and subpar canon, but from that canon emerges a few shining examples of success that are all the more notable for their rarity. They may be based on games, but these films aren't playing around.

A sinking ship

One obvious reason board game adaptations seem to be a losing proposition is scant workable source material. It's easier when the games in question are themselves adaptations of human activity, like military confrontation in Battleship or quests in Dungeons & Dragons. But Hollywood makes movies about war and quests all the time, and although adapting a movie from a board game may seem like a unique idea, the aforementioned games rely on fairly formulaic underlying themes.

This was one of the chief complaints against Ouija, a "low-grade ripoff" of Final Destination, in 2014, as well as Battleship in 2012. The latter film was "too loud, poorly written, and formulaic to justify its expense," critics concluded on Rotten Tomatoes, suggesting that viewers would get more pleasure out of playing the game itself than watching the adaptation. But surely an adaptation of Dungeons & Dragons, a collaborative, creative game in which the story varies each time, would have a far-from-formulaic sense of direction? You could say that — the 2000 film didn't have any clear direction at all, judging by its nomination for "Worst Sense of Direction" at that year's Society Stinker Awards.

Board games are designed to be formulaic — literally to be "played by the rules" — and to have only as much sense of direction as dictated by the roll of a die. It's the film's job, difficult as it may be, to preserve the ingenuity of the game without sacrificing the hallmarks of narrative, and it's far easier said than done.

Go for the unconventional

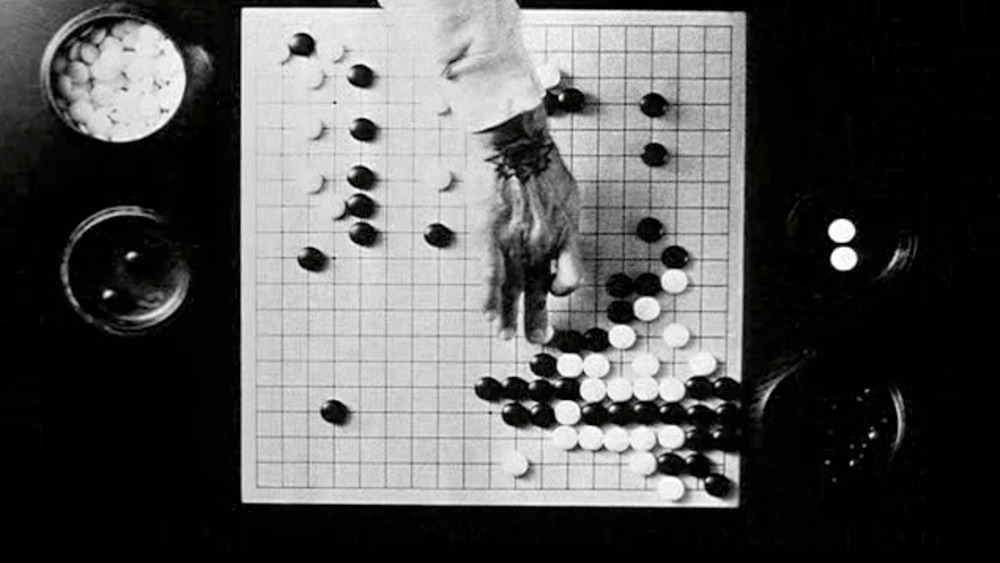

One oft-cited board game instructs us, "Do not pass Go," and in the case of The Divine Move, this is certainly advice worth taking: The 2014 film centering around the board game Go is not one we should consider passing up. Known as baduk in the film's home country of South Korea, the abstract strategy game serves as the locus for both the protagonist's betrayal and his revenge.

The title of this film suggests an especially brilliant moment of execution, and this can also be seen as a description of the film itself, which won the award for Best Editing at the 51st Grand Bell Awards. Director Jo Bum-gu acknowledged that baduk was an unconventional basis for an action film, given the inaccessibility of its jargon. The attempt to balance action, characters, and entertainment value was rendered even more ambitious by the fact that the game doesn't require any talking or action at all: It is simply a silent contest of the mind.

Rather than detract from the realization of this novel premise, however, it allows for more compelling psychological thrills and the way the power dynamics that rule the game of Go reflect the brutal realities of life. This makes the game, rather unexpectedly, the perfect foundation for an action-packed revenge story in which the white stone of wit and perseverance faces off against the black stone of violence, corruption, and domination.

From mini to max

The most popular miniature wargame in the world didn't beget the world's most popular film. That being said, Ultramarines: A Warhammer 40,000 Movie was well-received by advanced screening audiences ahead of its 2010 release, and praised for aspects of production for aspects of production like attention to detail.

Aside from some gripes with the CGI and animation of the film, the main issue with this feature is that it was made for such a specific audience. This is as much a shortcoming, however, as it is a hidden strength, because fans will enter into the experience with a sense of investment and understanding that exists independent of cinematic exposition. The plot may be regarded as simple by sci-fi standards — it's essentially the timeless story of a man on a mission to protect something valuable against powerful enemies on a cosmic scale.

This approach, though, is actually a brilliant preservation of the mechanics of gameplay and the manner in which tabletop games make each player a protagonist in their own epic for a short time. The film features mistrust and mystery buoyed by the details of character and set design, and whereas some board game films must elevate their source material in order to remain engaging in a cinematic sense, Ultramarines opts to capitalize on the aesthetic and logistical elements that make the game so well-loved in the first place.

A chess-inspired film gets the seal of approval

Don't think that a game of chess would make for a thrilling film? Try playing a harrowing match against Death himself, as star Max von Sydow does in the classic Swedish film The Seventh Seal. This mind-bending work from 1957 features heavy themes, from apocalyptic passages out of the Book of Revelation to the grisly years of the Black Death in Europe.

Chess is a game that requires a lot mentally from its participants, and the same can be said of the film. The medieval knight protagonist, Antonius Block, encounters many characters and circumstances that are not for the faint of heart. Block still begins the film by thinking he can beat Death at a chess game through a combined strategy of bishop and knight, whose ultimate failure is a metaphor for the ill-fated union of religion and military (Block has recently returned from the Crusades). He explores the connection between ideological fanaticism and religious wars, confronts his suspicion that his life has never held any meaning, and saves a girl from being sexually assaulted.

Block's escapades invite us to contemplate, as he does, the nature of mortality and God, before culminating in a Dance of Death. This departing dance at the end of the film is a nod to the artistic genre that illuminates the universality of death and its leveling power among all men.

Bend-all, be-all

The critically acclaimed animated sci-fi sitcom Futurama is just fanciful enough to pull off a board-game-based film, possibly because the series has already established itself as expert in the realms of spoof and parody, not to mention sci-fi and fantasy. Because of this, the 2008 direct-to-video film Futurama: Bender's Game has more latitude to explore a board game adaptation without taking itself more seriously than its source material warrants.

In addition to poking fun at the game Dungeons & Dragons, the film exploits classic fantasy and sci-fi film epics like Lord of the Rings and Star Wars and features the fan favorite foibles of classic characters already at home in a more mythical environment. The fact that the film is animated, rather than live-action, also helps steer it away from one of the "cheap look" pitfalls of the 2000 Dungeons & Dragons movie.

Instead, the film relies on the artistic sensibilities of Bender's "imagination processor" and the dark matter crystals that pull the characters into his fantasy realm, Cornwood, where everyone gets their own mythological analogue on a quest to wrest power back from Mom, the creator of the robots (or, as she is known in Bender's imaginary land, Momon). This movie succeeds because it employs familiar Futurama humor and whimsy to guide its viewers through a new landscape.

Secret weapon

Things didn't start off well for Clue, an adaptation of the murder mystery board game known by the same name in North America. The campiness might work on the tabletop, critics decided, but onscreen the concept veers toward farce, trading organic wit for the less effective weapon of mere novelty. The concept was undoubtedly a difficult one to execute, considering that the first writer on the project, playwright Tom Stoppard, worked for a whole year on the script before hitting a wall. Even after securing another writer and seeing the film through to completion, the initial reception suggested that it just couldn't be effectively pulled off.

But as with any mystery, not everything is what it seems. Over the years that followed the film's 1985 premiere, which included three alternate endings released in different theaters, the Clue movie has developed a real cult following. Writer-director Jonathan Lynn has recalled that he enjoyed the mental challenge of writing the script but still struggled to explain the endeavor to his friends, which is similar to how its fans feel when they try to justify their love to anyone outside the film's cult following. Exchanges like White stating that a man had threatened to kill him in public and Scarlet responding, "Why would he want to kill you in public?" are a sample of the endearing eccentricities that make this film delightful for those who "understand" its cryptic but quotable allure.

A creepy prequel

The second installment of the Ouija franchise did miles better than the first. In fact, uncannily enough, the 82% positive rating 2016's Ouija: Origin of Evil received on Rotten Tomatoes is 13.666 times better than the 6% rating earned by its predecessor, to which it serves as a prequel. In this case, these two infamously cursed numbers (unlucky 13 and 666, the Number of the Beast) seemed to confer some pretty good luck. If board game movies struggle to critically succeed, that strain is compounded by the uphill battle sequels and prequels often face. Writing for IGN, Adam DiLeo commented on this rare accomplishment and how terrific, in terms of both horror and comedy, the film Origin of Evil is its very first scene.

In Ouija, the main characters find themselves terrorized by the spirits of two girls and their mother who had an ill-fated encounter with the board decades earlier. The prequel tells the story of this family, immediately giving it access to more narrative depth than the original. The film offers us a consummate tale of family drama in addition to being surprisingly satisfactory in the scares department.

Ladder of success

With its subtitle "a didactic fiction about cartography" and original objective of promoting a new map exhibit at Paris' Pompidou Centre, taking its inspiration from a board game is probably the least obscure trait of the 1980 film Snakes and Ladders. Based on an ancient Indian board game on an ancient Indian board game whose modern version the U.S. is known as Milton Bradley's Chutes and Ladders, Snakes and Ladders slithers into the surreal when a man known simply as "H" wakes up in his car with no memory of how he got there and no sign of an accident.

You wouldn't expect a movie based on Chutes and Ladders to explore themes of truth, imagery, and the universe, but this "didactic nightmare," as the narrator calls it, does exactly that. Filmmaker Raul Ruiz believes that the "boring" moments are the most interesting in his preferred cinematic world inhabited chiefly by surreal images. In this movie, the surreal landscape is the ever-expanding cartography of the board game "H" has found himself immersed in after discovering two men playing it in a field.

Eventually, the scale increases to the size of the universe before the main character, who has identified the story as a nightmare, begins to wake up. While the film highlights the difficulty of "mapping" reality with images, even moving images, it maps (sur)reality pretty well.

A slice of life

It may seem like the references to Go in Pi are incidental, but what many viewers may not know is that this 1998 film — which marks writer-director Darren Aronofsky's feature debut — is symbolically based, at least in part, around a metaphorical interpretation of the strategic board game. The film all but comes out and says this when Sol, one of Pi's characters, explains that the ancient Japanese viewed Go as a microcosm of the universe.

By extension, then, its concepts underpin every story ever told, and particularly this story, which rests upon the idea that there are numerical patterns that explain the cosmos and all of life itself. Main character Max Cohen, a tortured, reclusive mathematical genius, stumbles upon a potential code from God — a narrative manifestation of the Go-inspired notion that infinite complexities can arise from a simple premise.

After chronic agony, Max seemingly finds peace at the end of the film. Because Sol's conception of Go can also be seen as a foundational metaphor for Max's mind: "Although when it is empty, it appears simple and ordered... the Go board actually represents an extremely complex and chaotic universe." Between comfort and chaos lie masterful movies like this one, which, with entertainment and suspense, challenge us to think critically about life in a way that doesn't give us knockout headaches.