The Untold Truth Of Conan The Barbarian

When we talk of barbarians these days, it's rarely in the context of the dismissive stereotype of less "civilized" cultures that the word once represented. Instead, we generally understand the barbarian as an archetype in fantasy fiction, or as a class in Dungeons & Dragons, which is almost the same thing. That idea of the barbarian as a brutal but often heroic warrior, frequently with many weapons and few clothes, comes primarily from one character. Before Dungeons & Dragons, before He-Man or Thundarr or Claw the Unconquered, there was Conan the Barbarian.

Conan was created roughly a century ago by writer Robert E. Howard. He's big, strong, and skilled at fighting. He's also smarter than you might expect from watching him swing his bloody sword in his loincloth and horned helmet. He's a wanderer, a warrior, at times a criminal, and at times a king. He has companions at times, and loves many women along the way, but he rarely gets too close to anyone. Before long, it's always time to move on to the next adventure.

Conan the Barbarian, who originated both a character archetype and a style of fantasy fiction, has wandered over the years from prose to comic books to film and TV. Let's follow those travels, and trace the history of an icon.

Created for Weird Tales magazie

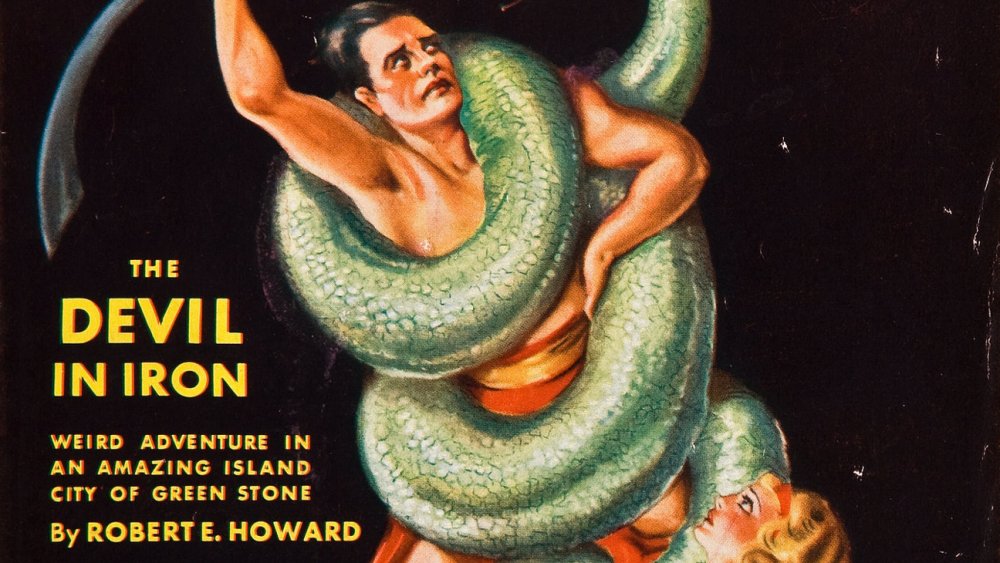

By the early 1930s, Robert E. Howard was already writing fantasy stories for pulp magazines like Weird Tales. He had previously created a barbarian hero named Kull, who lived in the legendary kingdom of Atlantis. In a 1931 story called "People of the Dark," which deals with reincarnation, Howard first mentioned a black-haired barbarian named Conan, who worshiped a god named Crom. He expanded on the character in 1932, when he rewrote a rejected Kull story into something new. He changed the title from "By This Ax, I Rule" to "The Phoenix on the Sword" and changed the hero from Kull to Conan.

The two characters were similar in many respects, although Conan was more interested in women. Also, whereas Kull hailed from Atlantis and had adventures on that mythical continent, Conan came from a place called Cimmeria, but never visited it in any of Howard's stories. Conan was always a wanderer, an outsider in the kingdoms where he found himself. Even when he became a king, as he did in that first 1932 story, it was through a combination of circumstance and his martial skill, never anything to do with birthright or inheritance. Conan swore by a god named Crom, but didn't exactly worship him, because Crom was a colder, more distant god than that.

Howard would go on to write a total of 17 Conan stories and novellas for Weird Tales, with the latter being serialized across multiple issues. An 18th Conan story by Howard was published in the magazine Fantasy Fan. By 1936, his interests as a writer had largely turned to Westerns, but that same year, upon learning that his mother was dying of tuberculosis and not expected to regain consciousness, Robert E. Howard died by suicide.

King of Paperbacks

The Conan stories remain Howard's enduring legacy. They were extremely influential among other pulp writers, and gave rise to the "Sword and Sorcery" subgenre of fantasy, marked by violent morally gray heroes, gritty — often personal — battles, and often at least a hint of sex, as opposed to the pure heroes and world-saving quests of more conventional fantasy.

Conan would move from magazine racks to bookshelves in the 1950s, with a series of collections by Gnome Press. The last of these, The Return of Conan, was the first Conan tale to be written by someone other than Robert E. Howard, in this case author Björn Nyberg. Another author, L. Sprague de Camp, revised the Howard Conan stories for these books and completed some unfinished stories, even rewriting some non-Conan Howard stories to make them about Conan. De Camp also revised Nyberg's book, giving the whole series a sense of cohesion.

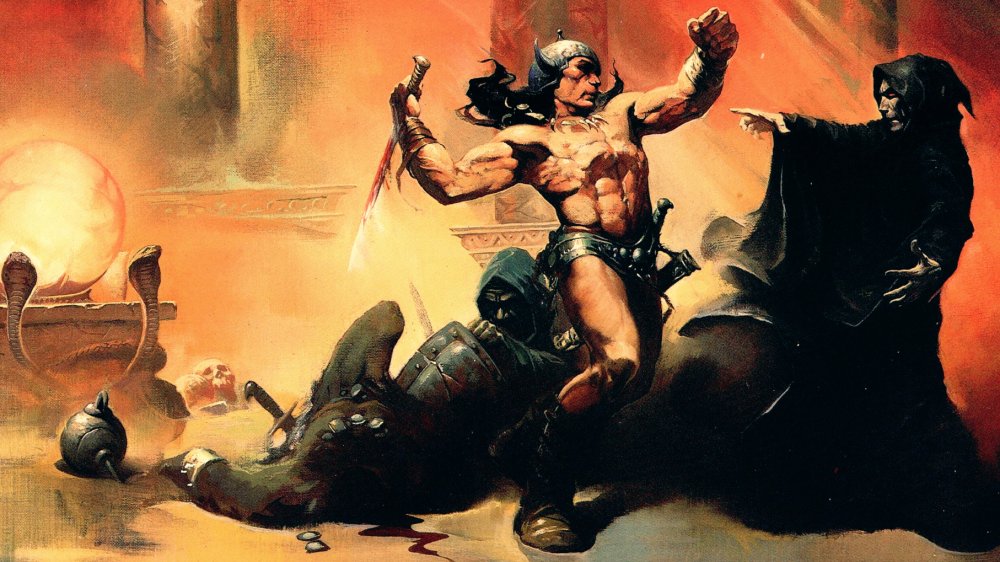

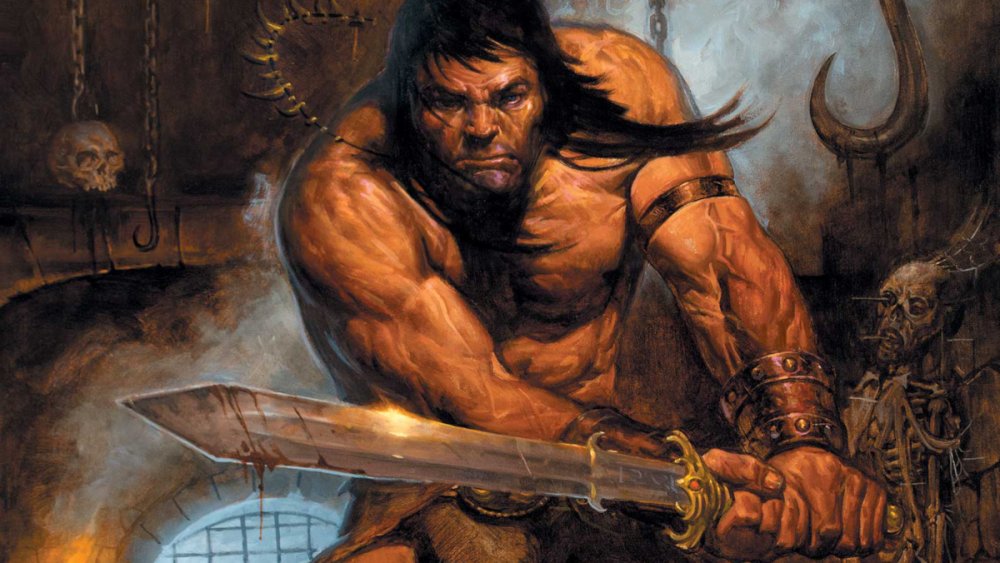

In the late 1960s, a publisher called Lancer got the rights to publish Conan in paperback, and it was these editions that would really cement the barbarian hero as part of pop culture. Of the 12 books published first by Lancer and then by Ace Books after Lancer went out of business, eight of them had painted covers by Frank Frazetta, who gave Conan his iconic look and cemented his own reputation as one of the greatest fantasy artists of the 20th century in the process.

Roy Thomas brings Conan to Marvel

In 1970, Roy Thomas was the executive editor of Marvel Comics. Over the course of the 1960s, Marvel had become hugely popular with college students and other readers somewhat older than previous comic books had catered to. As Thomas has explained in interviews, they would frequently get letters asking them to publish comics based on properties they didn't own, and one name that kept coming up was Conan. Thomas was a Frazetta fan who owned some of the paperbacks, but he hadn't really read them. Once he did, he realized how good Howard's stories were, and wrote to an address in one of the paperbacks asking if they'd license Conan to Marvel. The answer was yes, and Conan The Barbarian issue #1 was published in October 1970.

Roy Thomas himself wrote the comics, with talented newcomer Barry Windsor-Smith on art. As a duo their run on the character would become legendary in its own right, and over the course of the 1970s Conan became closely associated with Marvel. The success of Conan the Barbarian led to the launch of Savage Sword of Conan, a magazine-sized black and white comic that allowed for more adult stories. Thomas wrote the first 60 issues of that book too, this time joined by penciler John Buscema and inker Alfredo Alcala, among others. Both Barbarian and Savage Sword would last until the 1990s, with other Conan spinoffs along the way.

Conan The Barbarian (1982)

With Conan's popularity through the roof after more than a decade as a Marvel Comics star, it was only a matter of time before the Cimmerian wanderer made his way to the silver screen. It took several years for producers to get the movie made, but they knew early on that they wanted Arnold Schwarzenegger, then known mainly as a bodybuilder who'd appeared in the documentary Pumping Iron. His improbable build made him a perfect Conan, and the barbarian had never been verbose enough for Schwarzenegger's Austrian accent to be much of a hindrance. Anyway, Conan was always meant to be from a foreign land.

John Milius directed Conan the Barbarian, which was released in 1982 to some box office success, and it also became a big hit in the emerging medium of home video. Alongside Schwarzenegger, the film featured surfer Gerry Lopez as Conan's friend Subotai, and dancer Sandahl Bergman as Conan's doomed love interest Valeria as well as Mako Iwamatsu as the Wizard of the Mound. Max von Sydow and James Earl Jones brought some acting prestige to the production as King Osric and the evil Thulsa Doom, respectively. The story and characters strayed considerably from Howard's version of Conan, and they certainly had nothing to do with the Marvel comics, but Conan was still recognizable, and the adaptation was considered a success. It also made a Hollywood movie star out of an Austrian bodybuilder, enabling Schwarzenegger to move on to The Terminator, Commando, and Predator in quick succession.

Conan the Destroyer (1984)

When it came time to make a Conan sequel, to be titled Conan the Destroyer, the producers wanted something less violent that could be rated PG rather than R, which they figured would make more money. Veteran director Richard Fleischer was brought on to replace Milius, with only Arnold Schwarzenegger and Mako Iwamatsu reprising their roles. To fill out the cast, singer and pop culture icon Grace Jones was brought on to play the female warrior Zula, and basketball player Wilt Chamberlain, in what would be his only film role, played the guardsman Bombaata. Character actor Tracey Walter played Malak, an obvious replacement for Subotai. A teenage Olivia D'Abo made her film debut as Princess Jehnna.

The film is fun, especially for young audiences, but it doesn't come anywhere close to being as good as its predecessor. It's more memorable for the images of Schwarzenegger's Conan surrounded by the statuesque Jones, the absurdly tall Chamberlain, and the tiny D'Abo than for anything about its story or its set pieces. Wrestler Andre the Giant, who would go on to win hearts in The Princess Bride, makes a memorable albeit masked appearance as a big monster. If ever there was a movie that cast most of its stars for the size and shape of their bodies, it's Conan the Destroyer.

Conan comes to cartoons

In 1992, Robert E. Howard's gruff and violent barbarian completed his long transformation into a character for children with the debut of Conan the Adventurer, an animated series from Sunbow productions, the studio behind such Hasbro-based productions as G.I. Joe, Transformers, and Jem and the Holograms. Conan's animated adventurers would not prove quite as successful as those series, lasting two seasons before being rebooted as Conan and the Young Warriors, which in turn only ran for 12 episodes.

This version of Conan was friendlier and had a more conventionally heroic morality. In one episode, for example, he refuses to join a pirate crew because stealing is wrong, whereas Howard's Conan (or even Marvel's Conan) would steal if it served his purposes, and even joined forces with pirates in the course of his adventures.

This Conan led a team of adventurers created for the show. Zula was an African warrior similar to his Destroyer namesake, but male this time around. Jezmine was Conan's love interest, a former thief who'd reformed to join this law-abiding barbarian. Greywolf was a young wizard whose sibling had been turned into wolves, and he hoped to turn them back. Finally Snagg was a Viking-esque warrior from a rival nation to Conan's. The main villain of the series was Wrath-Amon, leader of a Set-worshiping snake cult who earned Conan's ire primarily by turning his parents to stone.

Conan the Adventurer (1997)

In 1997, Conan returned to TV for another series with the same title as his cartoon, Conan the Adventurer, but this time in live action. This was the era of the popular Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and its spinoff Xena: Warrior Princess, and Conan the Adventurer was an obvious attempt at achieving something similar — but it lacked those shows' charm, and ultimately their success.

With German bodybuilder-turned-actor Rolf Mueller as Conan, the series drew more from the Schwarzenegger movies than the original stories, but the character of Conan drifted even further from his source material. Mueller's Conan was friendly and jovial, and his power came more from pure brute strength than any particular skill or intelligence. Like in the animated series, he led a whole party of adventurers, featuring Danny Woodburn as the clever dwarf Otli, Robert McRay as a deaf warrior named Zzeben who communicated with sign language, T.J. Storm as the capoeira warrior Bayu, and Aly Dunne as Karella, the latest incarnation of Conan's fiery love interest.

Conan and his companions didn't even wander the world in this series. They spent their time attempting to free Cimmeria from the evil conquerer Hissah Zul (Jeremy Kemp), who was also responsible for the death of Conan's parents. Furthermore, the Cimmerian god Crom is no longer an absent, distant deity, but instead a central and active force in Conan's life. Conan the Adventurer only ran for one season.

Dark Horse brings Conan back to comics

In 2003, Dark Horse Comics obtained the rights to publish Conan, and over the next 13 years the barbarian was featured in a number of series which hewed closer to Robert E. Howard's original stories than any adaptation in recent memory. The first Dark Horse series, which was simply titled Conan, ran for 50 issues. It was followed up by Conan the Cimmerian, which lasted 25 issues. The third Dark Horse series, Conan: Road of Kings, lasted 12 issues and led into a comic with the familiar title Conan the Barbarian, which ran for 25 issues. Conan the Avenger also lasted 25 issues. The sixth and final Dark Horse series, Conan the Slayer, ran for 12 issues, ending in 2017. King Conan, a series featuring stories of Conan's reign as monarch, also ran for 24 issues, in parallel with the other books. There were also various miniseries and one-shots along the way.

The Dark Horse comics were very popular and proved the ongoing viability of Conan as a property. That led the company that brought Conan to comics in the first place, now backed by the Disney Corporation, to re-obtain the license from Dark Horse. Conan returned to Marvel Comics in 2019, with revivals of Conan the Barbarian and Savage Sword of Conan.

Conan The Barbarian (2011)

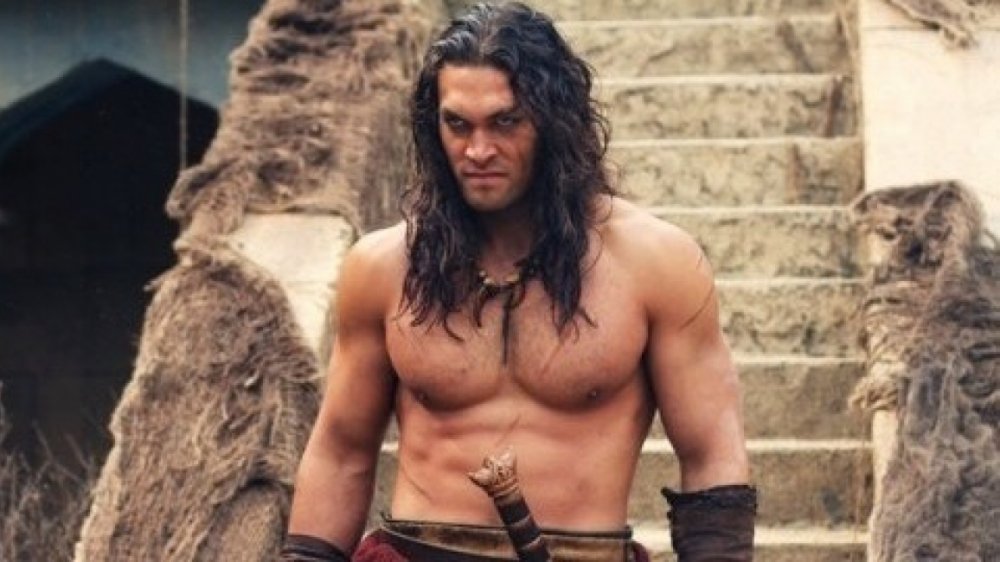

In 2011, with the Dark Horse comics going strong and a generation of adults with nostalgia for the Schwarzenegger movies, it seemed like time to relaunch Conan the Barbarian on the big screen. Jason Momoa, who at the time was playing the barbarian warlord Kal Drogo on HBO's Game of Thrones, seemed like a perfect choice to play the title role, and modern special effects could bring the Cimmerian's world to life on a whole new level. At least, that was the theory.

By all accounts, the movie just doesn't work. The writing is a mess, the dialogue is terrible, and the acting didn't win anyone over. And with those weaknesses, the level of violence, however faithful to Robert E. Howard it might have been, just didn't feel justified within the movie. Furthermore, it was filmed in 3D, which a lot of people seemed to be getting burnt out on by 2011, and it was criticized for particularly unnecessary 3D effects. The movie was a resounding box office bomb. The only one who escaped relatively unscathed was Momoa, who would go on to play another warrior-king, DC's Aquaman.

The Legend of Conan

At the very end of Conan the Destroyer, there's a shot of an older Conan — bearded, with graying hair — sitting grimly on a throne, a simple crown on his head. The narration lets us know that there's still a story yet to be told about how Conan became a king. That was going to be the third movie in the series, but it never came to pass. Or rather, it hasn't so far. In 2012, after Arnold Schwarzenegger's two terms as Governor of California had ended, and also after the attempt to launch a new Conan franchise with Momoa had failed, producers Fredrik Malmberg and Chris Morgan announced that they were bringing Arnold back for a third film, featuring an older Conan.

In a 2014 interview, Morgan compared the film to Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, a Western about a long-retired killer who decides to do one last job. It's easy to imagine the older Schwarzenegger as King Conan, having lived a relatively peaceful life for years, when something arises in his kingdom that requires him to take up his sword once more. Unfortunately, the project seems to have been dropped, but there's always a chance it will come back one day. In a world with movies like Rambo: Last Blood, Terminator: Dark Fate, and even Bill and Ted Face the Music, an elderly Schwarzenegger-played Conan may yet find his way to screens one day.

Netflix and beyond

Regardless of any possible future film projects, producers Fredrik Malmberg and Mark Wheeler started working with Netflix to bring Conan to streaming television. The developing deal would give Netflix the rights to all the Conan properties, which are owned by Cabinet Entertainment. Few other details are available so far, but there's exciting potential here. Looking at previous shows Netflix has made, one can imagine a Conan series with the dark fantasy imagery of The Witcher, the mature and engaging storytelling of Umbrella Academy, and even the unflinching violence of Ozark. If this show lives up to its potential, in other words, it could come closer than any other adaptation to what makes Robert E. Howard's Conan legendary.

Even if it doesn't, of course — even if this deal falls through, or the show that comes out of it isn't any better than Conan's last TV show (or his last movie) — Conan of Cimmeria will live on, and await the next project. Decades after his creation, Conan is more than a pulp fiction protagonist, a comic book hero, or a movie franchise. Conan the Barbarian has truly passed into legend.