Unpopular Opinions About Batman That Raise Good Points

There is no supervillain in the Batman universe called "Devil's Advocate" (though there is a 1996 one-shot comic of that name centering on the Joker). But sometimes the devil's advocate is Batman's greatest nemesis. All too often, fans' attempts to think critically or reject widely espoused opinions results in a muddled discourse that detracts from the subject matter as well as the fanbase itself, just because a couple Reddit commenters wanted to offer an "edgy" take.

True, diehard fans would much rather people just stop calling Batman a sociopath for clout, or musing and then posting to Twitter with the hashtag #showerthoughts "Shouldn't it be 'He is the hero Gotham needs, but not the one they deserve,' and not the other way around?" (This revision of Christopher Nolan's famous line sounds like it'd be unpopular, but it's actually a common thread that the deeper fanbase needs to correct time and time again.)

When fans put a lot of thought — as well as genuine devotion to the canon — into their analysis of Batman, there are a lot of revelatory points to be made. Often, they correct the superficial errors made by overzealous fans and popularized by more mainstream audiences. The analyses of the diehard fan base may be unpopular, but not for the sake of being unpopular. Like Batman, they expose difficult truths.

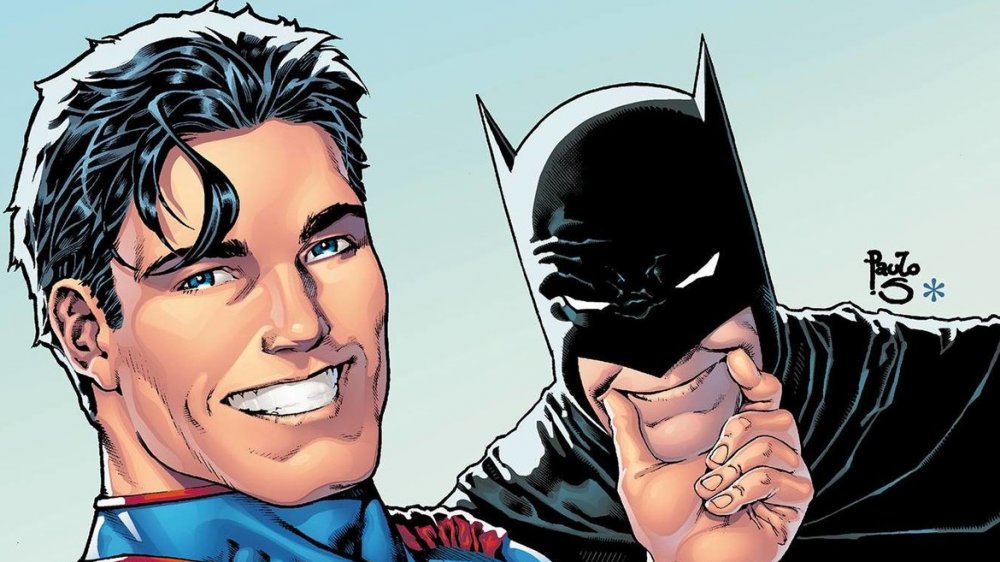

Batman and Superman should have a super-bromance

Batman and Superman should trust each other more and have a more pronounced allyship rather than the sometimes shallow "who would win" antagonism that appeals to some fans. The soured relationship between the two in Frank Miller's 1986 story The Dark Knight Returns wasn't very prominent before that point; in fact, Miller's comic inspired much of 2016's Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, if indirectly and decades later, due to the introduction of conflict into the foreground of their relationship.

On the other hand, Grant Morrison, the "anti-Miller," felt that the two should have more of a kinship or bromance, and there is a surprising if subtle intimacy reflected in his (and others') writing of the relationship. Both are orphans. Each provides a foil for the other, but this is inherent in each's personality and origin story and doesn't require an escalator conflict to be compelling.

In fact, more depth is achieved in the Morrison approach and with other writers who followed his pattern (as evident in the 2011 The New 52, 2003's Batman, and Justice League of America 1996 revamp, JLA) because there's actually a chance to explore rather than explode the relationship.

Holy Bat-dichotomy, Batman

In the realm of the Dark Knight, there is often little room for lighter gray areas. Most fans prefer to place Batman firmly in the camp of lucid or insane. A few, however, assert that the truth is much more nuanced than this simple dichotomy.

Batman exhibits extreme traits and behaviors, but even clinically significant symptoms are common. Some theorists go even further to speculate that he's a full-blown sociopath: The objectivity of his emotional void makes him a perfect vigilante. Others suggest that he simply acts from a strong sense of moral obligation that's derived from trauma.

It's easy to reduce Batman to a sociopath on one hand or a personally invested crusader for justice on the other. Proponents of the gray area would say that it's too idealistic to hope that underneath his dark mask lies a knight in shining armor with pure intentions, but on the other hand, you don't sound edgy calling him a sociopath — it's an insultingly simplistic take. While many opinions are controversial because they're divisive, the "gray area" view of Batman's sanity is controversial because it departs from the divisiveness of the debate, and detractors insist that it's overly complicated. Sociopath and savior are the two most popular and polarized positions on Batman's psyche, but maybe he deserves more. If he's the only thing standing between the innocent and the depraved, shouldn't his mental state also lie somewhere in between?

Miller the Batman killer

Frank Miller rewrote history. He took a license that went beyond poetic, comic, or literary — essentially giving himself a license to kill and rebirth the Dark Knight in order to conform the story to his own perceptions of the character. His execution was often brilliant, but he was also guilty of disregarding history in favor of grittiness — and revisiting his version of the Batman story with progressively more unpleasant results rather than quitting while he was ahead.

For a number of Batman fans, the darkness of Miller's vision was truest to the character, but it was eventually taken way too far. Eventually, Miller's Batman went on a problematic crusade against Muslim terrorists and descended into gratuitous violence. The very grittiness that gave Batman substance in Miller's earlier work ended up obscuring it later on.

At first, Miller let us see Batman bleed like never before, and we felt his wounds. But "like never before" shouldn't mean that Batman strays so far from what he ever was before that he essentially becomes a parody of himself, brooding and bleeding because that's what he does.

A villain's show

It's a tradition for the fanbase to freak out whenever a new Batman actor is announced. From Michael Keaton to Robert Pattinson, cinema's latest version of the character is almost always met with apprehension or downright disgust.

One section of the fanbase, however, contends that Batman is actually a relatively simple two-dimensional character, at least in the films. In the movies, the marriage of performance and writing is what makes or breaks the piece, and the opportunity to be compelling only lasts a few minutes at a time. This unique character challenge is one that we should demand the villains of the films to meet; whoever plays Batman isn't as big of a deal, because the burden of show-stopping should never be placed on his shoulders to begin with. After all, there's a reason we often discuss the best Batman movies in terms of the bad guys.

It's a way bigger deal when the villain sucks than when the hero does. Plot and character are driven by conflict, and conflict is driven by villains. The Batman franchise is a villain's show, full stop.

Man vs. Bat

When you get right down to it, the hardest part about casting Batman isn't actually casting Batman, it's casting Bruce Wayne. One of the central foundations of Batman's hero persona, and perhaps the way people expect or perceive him to be more three-dimensional than some fans think is warranted, is the fact that underneath it all, he's an ordinary human.

Batman has suffered human losses; he has ascended through the human ranks of wealth and society to amass his certainly super but not super-human resources; his backstory is one that connects him to the human experience and drives him to protect people because he is one of them, not because he is above them and chooses to be benevolent. Batman's motivation as a hero is unique because he understands what it means to need a hero and to build an empire that offers that protection. His vigilante alter ego gets all the attention, but these nuances can only truly be captured by the person playing Bruce Wayne.

The Grayson area

For most fans, Bruce Wayne is the only true Batman. Be that as it may, Dick Grayson should have gotten more time as Batman in Gotham. He deserved a shot like the tenure Wally West had between and concurrent with Barry Allen's runs as the Flash. (No pun intended.) Between the 2009 Batman: Reborn story arc and The New 52, which involved a bit of continuity alteration, Dick Grayson was somewhat unceremoniously ousted as Batman, reprising his role as Nightwing in the latter timeline. He deserved better than that as well.

Dick as Batman allows for more exploration of Bruce as the billionaire philanthropist and the power and scope that come with his resources. And this time, his own alter ego is his philanthropy. Dick's personality also brings a lighter tone to the Batman persona, without requiring the sometimes clumsy and heavy-handed ties to Frank Miller's dark and gritty Batman.

Over time, Dick has become more cynical like Bruce, which is itself an authentic depiction of a descent into darkness. Essentially, Dick Grayson's Batman opened up a lot of opportunities for the franchise — and too many of them were missed.

Bat's all, folks

Death is inevitable, even for comic book characters — and when his time comes, Batman shouldn't have some sort of meaningful death that ties up the depth of character and the intense story that fans love so much. Instead, he should just get hit by a stray bullet or his grappling hook should break, or maybe he should have a heart attack in the middle of hand-to-hand combat

Though the writer himself is polarizing, this is a bit of a Miller-esque take, one that highlights Batman's humanity and the ever-present reality of pain and mortality. Chance tragedy made Batman who he is, and chance tragedy should end him. Keep Batman Batman, especially in his last moments.

A related opinion is that while his gadgets do make him who he is, there should be a limit. There should be something differentiating him from Iron Man, who has similar resources but who definitely adopts a more flashy, arrogant, and performative attitude that defies constraint wherever possible. And on that subject, his mastery of just about every known martial art makes him almost reminiscent of Superman, too. Keep. Batman. Batman.

What's green all over and could be written better?

The Riddler is a great character, but not as he's historically written, because the writers don't properly understand him (and haven't devoted themselves to achieving that understanding the way they have with the Joker). He's not just some character from Saw or something along those lines. His greatest compulsion was creating and solving riddles. In fact, he occasionally attempts to pull something off without sending a riddle, but finds he can't resist.

This makes the Riddler a unique villain in that crime is not his true motivation. But he also doesn't need to be a "run-of-the-mil [sic] comic book psychopath," as one Redditor points out in an r/Gotham thread about the villain's wasted potential. Crime is simply the most urgent guarantee that the Riddler's compulsion can be satisfied. Of course people will solve your riddles if it's a matter of life and death. But where life and death are the ends of the Joker's schemes, for the properly nuanced Riddler, they can also be the means.

This, as the same thread points out, makes him a villain you can't technically defeat. If you solve the riddle and thwart the crime, he's still won: he's gotten you to play with him.

Villains, not vaudevillians

Not all the classic, campy Batman villains deserve a reimagining in the modern Batman. Of course, much of the original camp is inescapable and quite endearing — there's just something disarming about dressing evil in a brightly colored suit.

But that lightness doesn't have as much of a place in the Batman movies. For one thing, it would be difficult to capture onscreen without invoking slapstick humor or over the top performances. Even in the comics, where presentation leaves more room for humor without sacrificing impact, some villains just don't seem cut out for lengthy, recurring plots, and to bring them in here and there is also a waste of energy.

This opinion is more popular regarding less-loved members of Batman's rogues' gallery, but it also extends to supervillain tropes that fans believe are overcrowded by multiple characters. For example, the Mad Hatter is a green-clad obsessive-compulsive, like the arch-villain Riddler: though the mechanism of his mischief is different, does he really offer enough to the Batman canon to justify an entire additional character? Posing this question is what leads some fans to insist that certain goofier or redundant Batman villains should be left in the past.

More issues than Vogue

Most of Batman's mental issues (for those who argue they exist) are self-inflicted, which is a take that at first seems a bit insensitive to his trauma. One argument, though, is that if he's privileged enough to build a personal military arsenal, he can probably also afford a good psychiatrist (and hopefully not one who's also a villain, like the Scarecrow or Harley Quinn).

Some people like to think of the Batman persona as a triumph over past trauma and an aspirational, if warped, coming-of-age story. However, there is a lot of basis to the argument that Batman actually does more harm than good as far as addressing Bruce Wayne's traumatic past. Most therapists will tell you that dissociating from your own experience enough to create an alter ego isn't a great coping mechanism.

If we look at how Batman spends his days and nights, we see him directly causing Bruce Wayne to revisit many of the psychological wounds his actions were supposed to rectify. When he corners villains in an alley, is he reversing the strikingly similar trauma of his childhood, or re-inflicting it?

Dad-man

It isn't discussed as often as some of the other relationships in the canon, but Batman's long association with Jim Gordon is more important than Batman and Robin. Given that Gordon is often depicted as an older man, his relationship with Batman is in some ways the inverse of Batman's relationship with Robin — an interesting perspective that overlaps one father-son relationship in Batman's life with another. The only difference is whether Batman functions as the father or the son.

Adopting Robin gave Batman an opportunity to emotionally move forward from the trauma of losing his own father. However, it also opens the risk of Batman failing to protect his son where his father had ultimately succeeded in protecting him. Giving Batman a father figure in Jim Gordon is, on its face, perhaps less interesting. But it's what Batman deserves.

The Batman-Gordon relationship should also be free of the distractions of "monsters" except on occasion. Batman is there to help clean up Gotham. Many of his more outlandish antagonists make him feel more like a more ordinary superhero, and also distract from the Gordon relationship as well as his relationship with his personal mission. Family ties, whatever their form, are crucial to the character — their brutal severing is what gave us Batman in the first place.