Mistakes Marvel Can Never Erase

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The House of Marvel hasn't always been as big as it is today, and not all of the company's history is as heroic as the adventures of Captain America or Spider-Man. Since starting out as Timely Comics in 1939, they've created countless classics and repeatedly breathed new life into a troubled industry...and also done a few things they probably wish we'd forget. Here are a few of Marvel's biggest missteps.

Atlas distribution disaster

Marvel initially launched as Timely Comics before changing their name to Atlas Comics in 1951. That's when their problems really started. Publisher Martin Goodman distributed his own company's comics to newsstands until 1956, when he decided to outsource distribution to American News Company. Unfortunately for Atlas, American News Company completely collapsed soon after, the result of a lawsuit accusing the company of monopolizing the market.

Atlas' only choice was to distribute through their direct competitors' network, National Periodical Publications, who owned DC Comics. NPP was none too friendly to Atlas, and limited them to only eight comics a month—a huge drop from the 60 or so titles Atlas had previously published.

Atlas creator layoffs

Martin Goodman's distribution switch was a debacle on two levels. Not only did profits plunge, but because of the bottleneck imposed by National Periodical, Atlas had to fire almost all of their artists and writers. There was simply nothing for them to do.

At the time, Stan Lee was a gatekeeper for Atlas, approving and paying for any publishable comic pages, but Lee himself admitted much later in an interview with Comic Book Artist that he was a poor judge of quality. If he saw something he didn't like, he just assumed that he didn't understand it and paid for it anyway. As a result, the Atlas offices had a closet full of unused artwork that slowly chipped away at their budget. It was thanks to Lee's lack of judgment that Atlas had at least six months worth of comics to publish during their downtime—even if they might have been a little below the company's usual standard.

Tossing pages

Before comics were seen as collectible items for collectors to preserve under UV-safe plastic, original comic art was a means to an end. It was photographed, colored, printed...and then the originals were discarded. "We had no room for them. We gave everything away," Lee told Playboy. "Some kid would come up to deliver sandwiches form the drugstore and we'd say, 'Hey, kid, on your way out, take these pages and throw them somewhere.' If one of those guys had brains enough to save some stuff, he'd be a very lucky man right now."

While thousands of original, important pages have been preserved by collectors, early Marvel simply chucked countless others, not unlike the way the BBC tossed dozens of early Doctor Who episodes to make room. Today, finding any missing comic page is a victory for both collectors and comics historians.

Creator mistreatment

From the beginning, comics artists have generally operated under "work for hire" contracts with their publishers, and Marvel is no different. What this essentially means is that anything created for and bought by Marvel belongs to Marvel forever. Under these contracts, Marvel can do whatever they want with someone's work without further compensating or crediting the creator for the concept.

One of the worst examples of Marvel's questionable treatment of their creators is the case of Gary Friedrich, the co-creator of flame-skulled, motorcycle-riding anti-hero Ghost Rider. Friedrich took Marvel to court for compensation related to the merchandising of his famous character, but in 2010, he lost the lawsuit. As if that weren't painful enough, Marvel countersued Friedrich for $17,000, and forced him to stop selling anything Ghost Rider-related at conventions. Later, in 2013, a judge overturned the decision based on the questionable language of the old Marvel contracts, and both parties settled out of court.

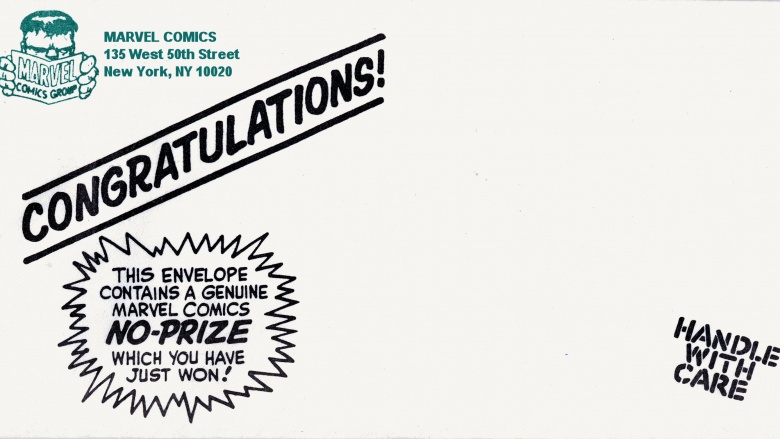

The No-Prize

In 1964, Marvel comics began asking questions of their readers, who would then respond and fill the letters pages of their favorite comics. Of course, such work couldn't go unrewarded, so Stan Lee started offering a luxurious "No-Prize," which was unfortunately a little too confusing for comic readers...because it was literally no prize but acknowledgement.

Lee upped the ante by inviting readers to spot continuity errors within Marvel's comics. Winners would be sent the No-Prize of an empty envelope. Still, this confused readers even more, who were disappointed upon opening empty envelopes from Marvel, and continued to demand actual prizes. Readers picked apart each panel of every comic in search of errors, the number of letters tripled, and ultimately, the practice was canceled in 1989 by then-Marvel owner Ron Perelman (although it has persisted, off and on, in some form over the ensuing years). But it was too late; nerds had been trained to nitpick comics into oblivion, ruining them forever for everyone who just wanted to have a good time.

Royal Roy

For a period, Marvel Comics also published Star Comics, a label almost exclusively dedicated to animated series tie-ins like ThunderCats and Fraggle Rock. This effectively kept Doctor Doom's malevolent magic away from the delicate minds of children. This was also the line that published the first issues of Peter Porker, Spectacular Spider-Ham, but that's best left forgotten.

Part of Star's modus operandi was to copy the success of Harvey Comics, both in their distinctive style and also in story. Star wandered a bit too close to Harvey's property, however, why they began publication of Royal Roy. The young millionaire was basically a copy of Harvey's Richie Rich, or a very lazy parody thereof. Complicating matters was the fact that an ex-employee of Harvey had created the character for Star. Harvey sued Marvel for infringing on their property, and Royal Roy was canceled after a handful of issues.

Ron Perelman

In January of 1989, Perelman bought Marvel for just over $82 million. Soon after that, he took the company public and increased comic prices, reasoning that real fans would follow along. Many did, but numerous Friends of Ol' Marvel thought their favorite books slowly lost their lustre. With a decrease in quality and an increase in price, Marvel was part of—and, possibly, a major contributing cause of—the great comic collapse in the '90s.

Perelman also used Marvel to purchase other trading card, comic, magazine, and sticker companies, sending the company $700 million into debt. The financial details get murky, but they're detailed in Comic Wars by Dan Raviv, in which Perelman is presented as a primary villain. Marvel ended this period on its last legs, and in the eyes of many fans, Perelman was largely to blame.

Film Rights

In the early '90s, Marvel didn't have any big plans to make movies for themselves, so they didn't really see a problem with licensing out their characters to a wide array of different studios. It was basically free money just for letting a studio leverage a well-known character, after all. Among the characters licensed out were the X-Men, Spider-Man, Black Panther, the Hulk, Black Widow, Captain America, Thor, and Iron Man—essentially splitting the Avengers into a half dozen different cinematic universes, years before the term had even been coined.

By 2005, Marvel had gained better financial footing and started buying back the rights to their characters—just in time for the rise of the superhero film genre. Over the next decade (and with the assistance of Disney's mighty four-fingered fist), Marvel reclaimed all of its properties except those stuck with 20th Century Fox: the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, and Deadpool. Spider-Man remained with Sony, but Marvel wrangled a special deal allowing the character to appear in Captain America: Civil War.

Captain America & The Fantastic Four

It makes sense that Marvel may not have seen the value of getting into theaters in the '90s. Every Marvel film prior to 1998's Blade was a failure, including (but not limited to) Howard the Duck, the terrible 1994 The Fantastic Four, and the unfortunate 1992 version of Captain America.

The first Fantastic Four was allegedly produced just so a small movie studio could legally retain the rights to the characters. When Marvel executive Avi Arad caught wind that it was actually headed for release, he quickly bought the film, reimbursed the production company for its costs, and buried it in a vault. It cost Marvel a few million dollars—on rights that were purchased for a quarter of that price—to try and save their brand from being cheapened by a low-budget flop.

This fiasco occurred only four years after the production of Captain America, which was stuck in development hell for eight years before finally being released direct-to-video. Made with a $10 million budget, the first Cap reported profits of just over $10,000. From these humble beginnings, Marvel's risen into one of Hollywood's biggest and most dependable moneymakers: the only Marvel-derived flop since 2000 is Punisher: War Zone (2008), which lost about $25 million at the box office.

Marvel Defiant

While most of Marvel's actions are arguably defensible, there are times when the company has been kind of a jerk. This is probably most evident in the case of Jim Shooter and Defiant Comics.

Shooter was hired by Marvel in 1976, and by the time he was fired in 1987, he had risen through the ranks to become the company's editor-in-chief. During his tenure, he was credited with revitalizing Marvel and implementing better treatment for creators, but at the same time, he insisted on strict deadlines and complete editorial control. This attitude alienated many top artists, who left to work for DC, contributing to Shooter's ultimate undoing. Marvel's ultimate revenge on Shooter occurred when his new company, Defiant Comics, announced an ongoing series called Plasm. Marvel's UK branch had ownership of a never-used character named Plasmer, and because the two names were somewhat similar, Marvel sued the life out of Defiant, costing the company $300,000 in legal fees and driving them completely out of business.

Marvel's Image

Creative ownership issues continued to plague Marvel even after Shooter's renovations, and tensions came to a head around 1992. Eight of Marvel's top creators went to Editor-In-Chief Terry Stewart and asked for a better deal: more money per page, more royalties for characters they created, and a fairer portion of what Marvel was raking in for their work. Stewart declined, and the artists left to form their own interconnected system of studios, all publishing together under the Image Comics banner.

When the news broke, Marvel's stock dropped, and the fallout was big enough to be featured on a 1992 episode of Moneyline. Image exploded and revolutionized how the comic industry valued creators, and while Marvel survived, they could have stayed ahead of the game—and saved themselves a lot of trouble—just by playing fair.

Guiding Light

In 2006, Marvel's EIC Joe Quesada thought it would be a great idea to partner with, of all companies, Procter & Gamble, mostly known for selling Pringles, bowel-loosening Olestra, and the soap opera Guiding Light. Because Wolverine couldn't be seen in diapers and Spider-Man has a known allergy to Pringles, that only left the soap opera.

To that end, Guiding Light aired an episode in which a long-running character was shocked by some Halloween decorations and briefly gained superpowers. Marvel wrote their own version of the story as a six-page mini-crossover, and though the hope was that the cross-promotion would encourage soap viewers and comics fans to walk on the other side, not many did, and Guiding Light only lasted a few more years before it was canceled.

Marvel's failed cross-promotions go back even further. In 1980, Casablanca Records came to Marvel and asked them to come up with a superhero comic which could tie into an as-yet-unnamed singer. The creation, called Dazzler, was given wicked disco clothes and the power to turn sound into energy. While Marvel produced the comics, Casablanca never actually secured a singer to perform as Dazzler on their label, leaving the publisher with a terrible disco-themed hero, just as disco was dying out. Marvel re-edited the premiere issue, which sold in huge numbers due to an unprecedented number of superhero cameos as part of Casablanca's demands. Today, Dazzler shows up mostly in X-Men comics, but is generally a pretty good reminder of how the comic world fares best when it doesn't try to create heroes on the whims of Underoos, Bombay Gin, or International Cardboard Manufacturers.

Firing the Gunn

Disney made headlines for all the wrong reasons when James Gunn was abruptly fired from his writer-director gig on Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3. The unexpected termination of the filmmaker took place mere months before production was set to begin on the spacefaring superhero sequel, and the circumstances behind the move remain controversial.

Officially, Gunn was axed in response to years-old social media posts full of bad attempts at dark humor. On its own, this wouldn't be the most contentious thing in the world — especially for the squeaky-clean Disney company. But as Guardians star Dave Bautista has repeatedly emphasized, the posts only re-emerged as part of a concentrated campaign by far-right agitators to get Gunn fired, presumably in response to Gunn's vocal stances against the alt-right.

For many commentators, it wasn't the fact that Gunn was fired that was so outrageous — show business can be brutal like that. What was most chilling, rather, was the swiftness of Disney's capitulation to an argument that, to many, reeked of political calculus and bad faith. Despite remarkable efforts by the cast to get the director reinstated, Disney stood by the decision — and some people still haven't forgiven them.

For his part, Gunn landed on his feet, being quickly scooped up by Warner Bros. to write and potentially direct a Suicide Squad sequel. But the firing has still left one of the MCU's best series feeling tarnished and potentially unfinished, leaving fans to wonder what could have been.

Marvel Studios waited far too long to make a female-led movie

Marvel made some important strides toward fair representation in Hollywood with Black Panther, but sadly it took the studio longer to find the nerve to do the same for gender equality. Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige has been discussing the possibility of a Black Widow movie for what seems like forever. Speaking at a press conference in support of the release of Iron Man 2 on DVD back in 2010 (via Screen Rant), the producer revealed that he had a few "concepts" for a Black Widow feature and had even spoken to Scarlett Johansson about them, but "The Avengers comes first."

The Black Widow movie was bumped to the bottom of the pile in favor of new male-led franchises and sequels in the years that followed. It wasn't until Warner Bros. and DC took the initiative with 2017's Wonder Woman and emphatically proved that female-led superhero movies could work that Marvel got on board with the idea, greenlighting Black Widow and fast-tracking Captain Marvel. But why did it take so long for Marvel to give a female superhero center stage?

"I think there are a lot of reasons," Feige told Entertainment Weekly. "Not the least of which was fighting for many years the erroneous notion that audiences did not want to see a female-led hero [film] because of a slew of films 15 years ago that didn't work. And my belief was always that they didn't work not because they were female-led stories, they didn't work because they were not particularly good movies."

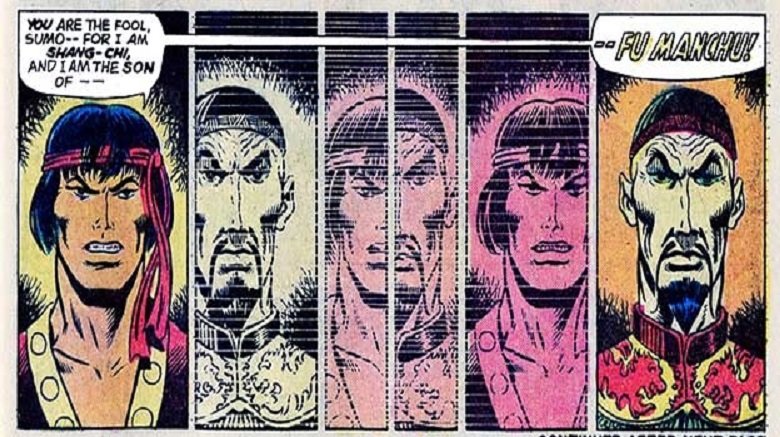

The curse of Fu Manchu

There was a time when Marvel would jump on any bandwagon that happened to come along in order to widen its audience. When the Kung Fu craze blew up in the 1970s, the company was all over it. The initial plan was to adapt the David Carradine TV show Kung Fu, but after failing to come to an arrangement over the property, Marvel purchased the rights to Fu Manchu instead.

Fu Manchu was created in 1912 by pulp novelist Sax Rohmer, who described the Asian villain as "the yellow peril incarnate in one man" during his debut appearance in The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu. Rohmer even likened Fu to Satan, calling him an enemy that embodies "all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race." It's not hard to understand why many fans were unhappy about Marvel's acquisition of this not-so-subtly racist evildoer. The character remains a black mark on the company's history, and the issue is set to become a hot one again as Marvel Studios enters Phase 4.

In 2018, news that a Shang-Chi movie was being fast tracked broke. Marvel reportedly hopes to recreate the magic of Black Panther, but there's one problem — Shang-Chi, an original Marvel creation, is actually Fu Manchu's son, a fact that has angered some Chinese fans. "You used Fu Manchu to insult China back in the day," one unimpressed Weibo user said. "Now you are using Fu's son to earn Chinese people's money, how smart."

That tone-deaf diversity interview

Kevin Feige made his intentions crystal clear when he announced that the cast of Black Panther would be 90 percent African or African-American — Marvel movies were going to embrace diversity going forward. We've already covered the upcoming Asian-led Shang-Chi movie and the fact that the studio is belatedly embracing female heroes, but that's just the movie branch of the company. For a while it seemed as though Marvel Comics was going to follow the same path, but in a 2017 interview, Senior Vice President of Sales David Gabriel appeared to complain about the company's new emphasis on diversity.

According to Gabriel, sales figures suggested that it wasn't what Marvel fans really wanted. "What we heard was that people didn't want any more diversity," he told ICv2. "They didn't want female characters out there... We saw the sales of any character that was diverse, any character that was new, our female characters, anything that was not a core Marvel character — people were turning their nose up against."

Naturally, the interview led to a backlash, and Gabriel was forced to release a statement clarifying his comments. He claimed that Marvel bosses were "proud and excited" about the new range of diverse characters, but they did little to push them. "Marvel hoped new, diverse characters would reach a diverse audience but it seems they hoped they would do so on their own," ScreenRant reported when the Marvel Legacy relaunch was canned less than a year after it was introduced.

The MCU timeline is broken

The Marvel Cinematic Universe is known for being a well-oiled machine, making the whole extended movie universe thing seem easy by planning ahead years in advance. That's true for the most part, but the MCU is far from watertight. In fact, its timeline has some major issues. When fans of the films began to point out these discrepancies, Marvel responded by releasing an official MCU timeline, which can be found in the Marvel Studios: The First 10 Years source book.

The questions began when viewers noticed that lines of dialogue and title cards in the Sony-Marvel collaboration Spider-Man: Homecoming stated that the movie takes place some eight years after the events of The Avengers. This didn't seem to tally, and Avengers co-director Joe Russo confirmed that it was indeed an error, telling journalist Ashish Chanchlani that "It was a very incorrect eight years." The official timeline rectified this (it confirmed that The Avengers took place in 2012, while Homecoming actually happened during 2016) but it raised more questions at the same time.

Dialogue in Infinity War states that the third Avengers film takes place two years after Captain America: Civil War, but the timeline places them just a year apart. "The most problematic is the moving of Black Panther, which dates itself just a week after Civil War; it hardly makes sense for T'Challa to leave his people without a king for a year," ScreenRant highlighted. Try as it might, Marvel just can't fix the timeline.

Political propaganda hidden in X-Men comics

In 2017, a Marvel comic made headlines across the world for all the wrong reasons. The company re-launched its X-Men line in April of that year, but what should have been a time for celebration quickly descended into controversy thanks to Ardian Syaf, a Muslim artist who decided to hide political and religious references in X-Men: Gold #1.

On top of referencing the date of a protest held in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta, Syaf drew X-Men leader Kitty Pryde (a Jewish character) in front of a jewelry store but made it so the first three letters of the word were particularly prominent. He also drew fan favorite Colossus in a T-shirt with "QS 5:51" daubed across the chest, a reference to an anti-Semitic and anti-Christian verse from the Koran.

"Do not take the Jews and the Christians as allies," the verse in question reads, per the BBC. "Whoever is an ally to them among you — then indeed, he is [one] of them. Indeed, Allah guides not the wrongdoing people." It's easy to see why readers were upset about the message Syaf was secretly peddling, a message that goes against the theme of X-Men comics.

"These implied references do not reflect the views of the writer, editors or anyone else at Marvel and are in direct opposition of the inclusiveness of Marvel Comics and what the X-Men have stood for since their creation," Marvel said in a statement. Needless to say, Syaf was fired.

HYDRA Cap

In August 2017, Marvel inexplicably spoiled the ending of its Secret Empire event, allowing The New York Times to print an in-depth preview of the then-unreleased 10th issue. It was seen as a jerk move by Marvel, but in truth this was just the tip of the iceberg — the company had been in a very public spat with fans since 2016's Captain America: Steve Rogers #1. It was during this explosive issue that Marvel's star-spangled Avenger turned to the dark (and by dark, we mean fascist) side, with Steve Rogers revealing himself to be a HYDRA agent.

The fact that HYDRA is essentially an offshoot of the Nazis didn't seem to matter to Marvel, though it mattered to fans. Petitions were started and hashtags like #SayNoToHYDRACap and even #BoycottMarvel appeared on social media. The company begged for patience, putting out a plea for calm via ABC News. Marvel even sent out HYDRA T-shirts to comic book stores, a tone-deaf move that didn't go down very well. "The last thing I want to do is force my queer, Jewish employee to wear a Hail HYDRA shirt," Greg Gage from Utah's Black Cat Comics told The Guardian.

Marvel kept telling fans to hang tight, and in the end HYDRA Cap was defeated. But was it worth it, or was the whole thing a huge mistake? "It's irresponsible to play sleight of hand with potentially volatile and offensive imagery just because 'it all works out in the end'," Polygon said during its Secret Empire autopsy.

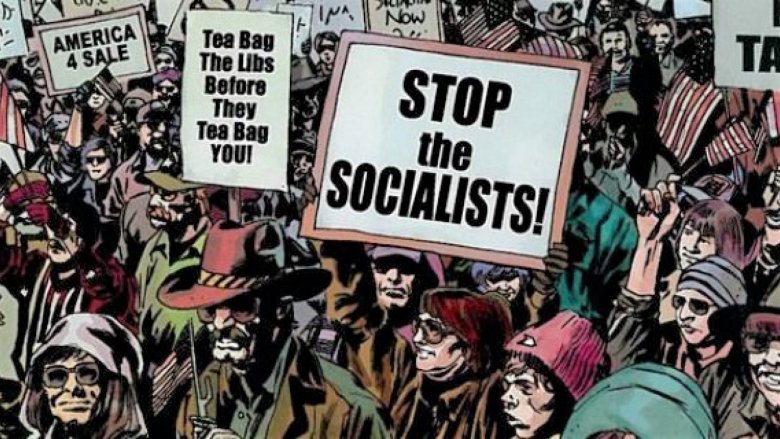

Marvel has a Tea Party

Secret Empire wasn't the first time a Captain America story arc kickstarted a political debate. Steve Rogers took a back seat in 2010's Captain America #602, with Bucky Barnes instead leading the line. During his investigation into an extreme right-wing group called the Watchdogs, Barnes and Sam Wilson find themselves surveying a government protest in small-town Idaho. There's nothing wrong with portraying a fictional protest, but this demonstration was quite clearly based on the Tea Party movement, a hot topic in American politics at the time.

The slogans on the banners carried by the all-white protesters were lifted directly from those seen at Tea Party gatherings, with phrases like "Tea Bag The Libs Before They Tea Bag YOU" making it pretty clear who these people were supposed to be. Fox News reached out to Ed Brubaker (writer of the controversial issue) for comment, and he told them that somebody in "lettering or production" must have added the slogans at the last minute. "I don't know who did it, probably someone who thought it was funny," Brubaker claimed. "I didn't think so, personally."

Joe Quesada (Marvel's editor-in-chief at the time) acknowledged the mistake in an interview with CBR, but for many, Marvel's real error was apologizing. "It may not play in every corner of the country, but for a company that makes its bread telling tales of heroic ideals, standing up for something might be just the kind of great responsibility that goes with their great power," Comics Alliance argued.

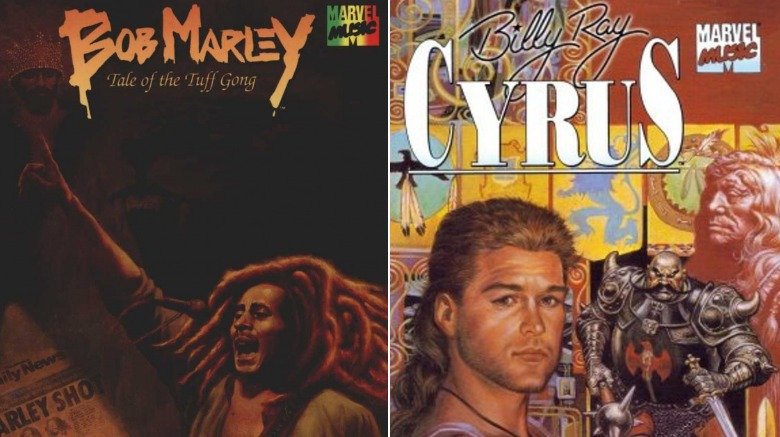

Marvel Music

Marvel has had some pretty wacky ideas over the years, but Marvel Music has to be one of wackiest. Rock legends Alice Cooper and Kiss had already starred in comics in the '70s when the company decided to resurrect the idea of inking musicians in the mid-'90s, at a time when comic books were once again big business. "The Marvel Music imprint aimed to not only revive the forgotten rock-comics genre, but elevate it to new heights, both artistically and commercially," Spin magazine's David Grossman said in a detailed piece covering this ill-conceived venture. "In the end, Marvel Music mostly served as a vehicle for the higher-ups at a newly rich company to hang out with rock stars."

Comics starring Billy Ray Cyrus, the Rolling Stones, and even Bob Marley were hastily put together, but Marvel just couldn't figure out how to market them, much to the dismay of Mort Todd, head of Marvel Music. "They didn't know how to sell anything that wasn't superheroes," he alleged. "So I was infuriated with Marvel and didn't renew my contract."

The dud imprint was pulled in 1995 and Marvel filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy the following year.

Avengers Disassembled

Brian Michael Bendis joined the Marvel writing staff in 2000 and quickly made a name for himself working on the Ultimate Spider-Man series. His Marvel career got off to a flying start, but his relationship with fans would turn sour in 2004 when he was given creative control over Earth's Mightiest Heroes. Buoyed by the success of his Spidey run, Bendis went in hot and decided to shake things up big time. Instead of easing himself into the title, he chose to "blow things up" and disassemble the Avengers, killing off Hawkeye and scattering the remaining team members.

"Some fans liked it, and some hated it," Bendis said. "There were a lot of arguments online, and a fan said to me, 'We're Avengers fans. All we buy is Avengers, and we have no idea who you are, but you came over and kicked all our toys over.'" The writer held his hands up and admitted to his mistake, but Avengers Disassembled would hang over Bendis for the rest of his time at Marvel.

In November 2017 — some 18 years after he first put pen to paper for Marvel — he jumped ship and signed an exclusive deal with DC. When he spoke to CBR a few months later, the new Superman writer pledged that he wouldn't make the same mistakes that he made on The Avengers. "It's not that I would have changed the story of Avengers," he explained, "but the glee with which I did things, I could have been more cool with."

The Akira Yoshida problem

Just weeks after Brian Michael Bendis departed for DC, Marvel's editor-in-chief Axel Alonso also left the company without explanation. Veteran writer C.B. Cebulski took his place at the top, but his reign was destined for a rocky start. The week after he was announced as the new head honcho at Marvel Comics, Cebulski admitted that he'd previously written under a pseudonym.

Akira Yoshida was once a mysterious character in the comic book world, gaining notoriety in the mid-2000s for his work with Marvel, who were desperate to find foreign writers that could create authentic stories for the American audience. As it turns out, Yoshida wasn't a fresh foreign voice at all. Cebulski had been masquerading as a Japanese writer, inventing a full backstory and conducting interviews. Marvel editor Mike Marts even claimed to have met the guy. "When we had lunch he showed me pictures of his immense Godzilla memorabilia collection," he said. "I was jealous!"

Among the outlets that managed to score a rare interview with "Yoshida" when he was active was CBR, and the website's Assistant Editor Jon Arvedon was not happy when he found out about Cebulski's deception. "One or more people were fully dedicated to perpetuating this nearly endless trail of dishonesty to maintain the false aura of authenticity surrounding the mysterious Akira Yoshida," he wrote. "Cebulski finally owning up to it is certainly a small step in the right direction, but the damaged reputations and the harm done to writers, artists and readers may take years to repair."