Barry Season 4 Follows A Harmful Prison Trope, And Future Antihero Shows Need To Avoid It

Slammer. Hoosegow. The box. Upstate. The prison system looms large over the American imagination, as evinced by the wide variety of synonyms and euphemisms used to invoke it. As well it should, since the United States incarcerates a higher percentage of its population than China, Iran, or even North Korea. Though home to only five percent of the world's population, the United States accounts for a quarter of its imprisonments.

Nowhere is our national fixation on the carceral system more visible than on television. Police procedurals air by the dozens, and even when a show is not explicitly about them, cops always seem to lurk about the periphery, implying — by their presence — the threat of incarceration. Prison is the background radiation of American culture.

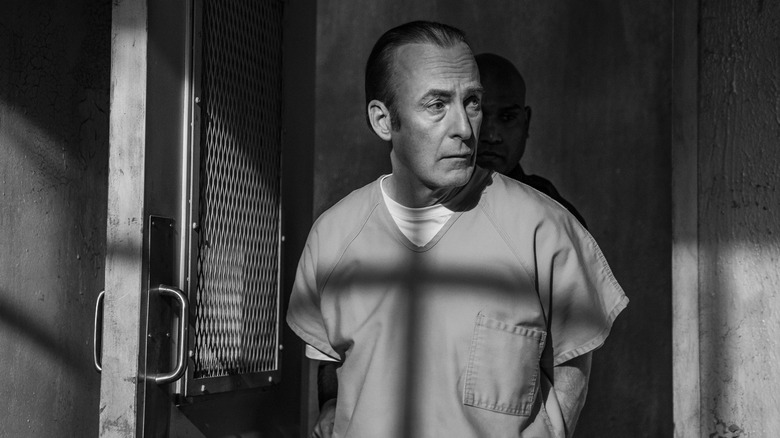

That's certainly true of "Barry," a show in which cops have played a key role from the get-go. Their presence is fair enough, since Barry Berkman (Bill Hader) is a seasoned assassin who's been doing an awful lot of murdering between his acting lessons. But with Season 4 of "Barry," the final chapter in Bill Hader and Alec Berg's HBO antihero dramedy, the titular hitman-cum-actor is now behind bars, having been arrested in the Season 3 finale for the murder of a police officer committed in Season 1.

On its own, Barry's imprisonment would be of little note. But taken together with several other dark, antihero comedies, such as "Better Call Saul" and "BoJack Horseman," that have turned to prison as a remedy in their final seasons, it becomes part of a disturbing trend that perpetuates harmful ideas about our criminal justice system and makes for unimaginative TV, that restricts the limits of our collective capacity to envision a better future.

Prestige and penance on antihero shows is a common theme, and Barry is following this trend

The rise in what has been called prestige TV brought with it a cavalcade of morally compromised protagonists. These characters, known as antiheroes, shock and delight us in equal measure. Though they may commit unforgivable sins, they are made sympathetic through a complex portrayal of their psychology. We are forced, when watching their exploits, to question the nature of humanity. The very core of the antihero genre is to ask whether people are capable of change, and, if so, whether penance is possible.

Penance, of course, being derived from the Latin "paenitentia," meaning repentance, the same word from which we take "penitentiary." Translated directly, a penitentiary is a place one goes to repent. The religious implications of the word are far from coincidental. In fact, the first solitary confinement cells in America were built by Quakers, who believed that separation from society would give sinners a space free from the influences of the world and their fellow man, a space of purity that would reconnect them with God.

Today's prisons, far more industrialized than ever before, are still widely conceived of as a space for rehabilitation. The notion of "serving time" takes on an almost ascetic aspect in our culture; just as the wayward monk wears his threadbare robes and fasts for his sins, the inmate solemnly endures his incarceration, dreaming of a glorious rebirth. Absolution comes to the monk from on high, but it comes to the American inmate from Uncle Sam.

That this is how we view prison is worth questioning, especially when it is repeated to us ad nauseum in popular media, as has frequently been the case with some of the best television series in recent memory.

An assasin, a lawyer, and a horse walk into a prison

For characters like Saul Goodman, BoJack Horseman, and Barry Berkman, the trip to prison becomes less an imposed punishment than a religious pilgrimage. Salvation comes in the form of three hots and a cot and mortification of the sinning flesh at the broadside of a billy club.

In the "Better Call Saul" finale, Goodman bares his soul to a higher power — not God, but a judge. Just as one cannot lie before the Almighty, the mythology of the American court demands honesty. Better to confess your sins and endure the penitentiary than to lie and remain free. After a lifetime dodging accountability, Goodman repents, and goes willingly to prison. Sentenced to 86 years, he will live out the rest of his days in a supermax facility. In the last shot of the acclaimed series, he stares knowingly from behind the prison fence with the weight of sin lifted from his shoulders.

In the final episode of "BoJack Horseman," the salvation of a supermax prison comes, too, for the worst horse in Hollywood. Asked what he's locked up for, BoJack answers, "Officially, breaking and entering, but I think it was kind of for everything." Even in a world of anthropomorphic animals, prison offers a chance at atonement.

Now, in the final season of "Barry," our titular thespian assassin is offered a chance at self-abasement. But unlike Saul or BoJack, he rejects imprisonment as a chance at purgation. In advance screeners provided to the press, Barry continues to insist, "I've been nothing but good to people. I'm a good friend. I'm a good person. That is who I am!" Because he has not accepted the purifying light of imprisonment, Barry cannot reap its cleansing rewards.

Fictional depictions of prison, as in Barry, cover up a horrifying reality

That the purpose of prison is to reform and rehabilitate is fundamental to the way these shows approach incarceration. However, it is an interpretation that causes very real harm. Not only do modern prisons fail to rehabilitate offenders, they've been shown to increase the chances that someone will reoffend after being released (via JSTOR Daily). But that's not all. As noted by the American Psychological Association, incarceration worsens prisoners' mental health, adding another barrier to a person's ability to rejoin society upon release. For the large percentage of inmates who already suffer from serious mental health conditions, there are seldom adequate psychological services to accommodate them, leading to further deterioration.

The body, too, is punished by imprisonment. Guards routinely inflict physical abuse with fists, batons, boots, and cattle prods. Inmates have been subjected to waterboarding, sleep deprivation, and mutilation — torture tactics that drew public outcry even when used against prisoners of war at facilities like Guantanamo Bay as pointed out by Human Rights Watch.

It can't be that bad, you may say. If it were, wouldn't there be outrage? Wouldn't we have changed things? Indeed, many activists have demanded prison reform for decades. But since the brutalities of prison are carried out behind closed doors against people for whom the general public has no sympathy, and who cannot advocate for themselves without risking further punishment, change is unlikely to happen without significant political support.

What certainly doesn't help is the continued depiction of prison as a solution to criminal behavior. Although Barry, BoJack, and Saul deserve their just desserts, doling out that comeuppance in the form of prison only further normalizes the everyday barbarities that occur behind those walls in real life.

Sending antiheroes like Barry to prison is a defense of the status quo

The depictions of prison in these and other antihero shows function as "copaganda," ideological propaganda that positions the American criminal justice system, especially law enforcement, as fundamentally necessary to and good for a stable society. At times, copaganda may even acknowledge negative aspects of the system, but even then, it only serves to hammer home the notion that, despite its flaws, the system is ultimately working. Barry may be beaten by guards, but it is framed as par for the course. By buying into the idea that prison can offer repentance or rehabilitation, shows like "Barry," "Better Call Saul," and "BoJack Horseman" end up conveying those same impressions to viewers, subtly influencing them to accept mass incarceration as a net good for society, or at least a necessary evil.

In fact, the carceral system could not ask for more effective propaganda vehicles than prestige TV series. When, in the course of abusing their power, law enforcement officials defend themselves in real life, the official narrative can be questioned, investigations launched, and journalistic reports published. But when representatives of the carceral system are characters in a work of fiction, no such rebuttals can be made. The political message is subsumed into the larger whole. Police and prisons are hardly the point of these shows, and viewers may not be focusing on the depictions of those elements within the narrative, allowing the propaganda therein to be absorbed subconsciously.

Sending antiheroes to prison is bad writing, and Barry should be do better

Isn't it more realistic, you might ask, for an antihero to end up behind bars? Isn't that what happens in real life to people like Barry Berkman? Perhaps, though real life police fail to solve about half of all murders even as the prison population balloons. However, television is not real life. Writers are not bound by reality, and even when attempting to recreate it, they can only create a platonic facsimile. The prison trope for antiheroes is a deliberate choice made by television writers — one that perpetuates harmful ideas about the realities of the justice system.

Plus, we are talking about shows where animated horses have Hollywood careers, hit men become actors, and lawyers deal methamphetamine. These shows are about as far away from reality as you can get, and to claim they sent their main characters to prison because it was the most realistic outcome ignores that their narratives are not fated, but written by people. Does the American obsession with prison have such a grip on our collective imagination that the people who are paid to invent new realities fail to do so?

Antihero shows used to know how to deliver an imaginative ending. The life and times of Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) was cut short in a moment of pure anxiety. Don Draper (Jon Hamm) got to meditate on a beach. And Walter White (Bryan Cranston) lived out his final moments caressing the steel instruments in a meth lab, the only place he ever found happiness.

As a metaphor for repentance, prison is a bleak one. As a plot point, it's boring. And as a trope, it's actively harmful. It's time to break out.