The Ending Of Tetris Explained

Tetris is an abstract puzzle game that took the world by storm in the '80s — and likely has a million bootleg versions in your friendly neighborhood app store to this day. The Apple TV+ movie "Tetris" tells the impossible — and more than slightly fictionalized — tale of what it took to bring those little falling blocks out of the Eastern Bloc and into hands and Gameboys (and eventually smartphones) all over the world.

While a movie about a video game might sound like a joke out of "30 Rock," "Tetris" has a little more meat on its bones — and a lot of fun and thrills exploring themes of greed, gaming, and how one wins at life. Making "Tetris" a thrill ride isn't as difficult as one might first think, and the cast and crew pull out all the stops to make the movie worth the screen time audiences could otherwise spend playing the actual game itself.

Noah Pink's original script was called "Falling Blocs" and its angle on fighting the Cold War via video games is what initially attracted director Jon S. Baird to the story. Baird told Big Issue, "It wasn't that the heroes are coming from the West and the baddies are from the East. It was very much like a case of there's good and bad everywhere." Read on as we connect the dots and arrange the blocks to win the game — and give you the ending of "Tetris" explained.

Capitalist cowboy

Henk's commitment to capitalism is very entertaining, very Western, and very dangerous. Even though Henk Rogers (Taron Egerton) is Dutch, his ability to kill colleagues with conversation and inability to take no for an answer rings a very "American Entrepreneur Movie" note. But while Henk's dedication and unwavering pluck in the face of failure makes him charming and admirable, his desire to always be closing — or finally be closing — might just get him killed.

Henk starts "Tetris" wanting to keep Bullet-Proof Software, the company he co-founded with his wife, from going under. He takes out loans, spends time away from home, and travels to the heart of anti-capitalism to wrest the future he believes he deserves from the iron fist of '80s-era Cold War Moscow. Henk starts the movie off meaning well, and ends it meaning better, but spends the entire film being reckless with his family, with money, and with the K-G-freaking-B.

Of course, Henk also does "win" the game of capitalism by winning the rights for Tetris. One might cheer for him at the end of the film, but not so fast. What makes warm, charming, well-meaning Henk a wild card is that he knows how much danger he's putting himself, his family, and Alexey's family in — but he does it anyway. Henk stops at nothing to get what he wants — and needs — when it comes to Tetris.

Cold War kid

Alexey Pajitnov (Nikita Efremov) creates the game of Tetris to experience some joy. While Henk is all bright colors and sunlight, Alexey and his world are literally muted. Viewers can see the toll living in Soviet Russia has taken on Alexey as he trudges through a gray existence, rocking sad-sack knitwear and a hangdog look. Alexey smiles when he creates games, especially Tetris, and the delight of playing and sharing them is his own act of quiet revolution.

Alexey seems resigned to hide his true self and full potential from his own country — until he meets the relentless Henk Rogers. It isn't that Henk activates Alexey's independent spirit, or inspires a lust for money. Henk's love of Tetris reminds Alexey not to hide his light under a bushel — or his falling blocks. Alexey is the embodiment of individualism the Soviet Union (and the KGB) seeks to suppress — as well as a team player to the bone.

Alexey creates Tetris out of joy, and sees how Henk can help him share that joy with the world — but Alexey's desire to serve the greater good with his game is tempered by fear. Alexey's no cowboy — he can't disregard the very real (and violent) repercussions his family faces if he flies in the face of authority. Alexey doesn't want what happened to his father to happen to him, or his loved ones. If Henk's philosophy runs on "no risk, no reward," Alexey's is more "no risk, no watching my children get killed in front of me by the KGB."

For the love of the game

Henk Rogers (Taron Egerton) really does love Tetris — possibly as much as the mega-check he hopes will accompany it when he finally secures the handheld rights. Cringey motivational sales slogans and "Wall Street"-esque movies might go on about what really separates the men from the boys, but what sets Henk apart from his fellow capitalist vultures is his literal love of the game — and all games.

Alexey and Henk have their first magic moment when Henk turns off the sales speak after a secret (and highly illegal) dinner at Alexey's apartment, and the two play Tetris together. The duo even end up making some improvements to the game on the fly, and two stories are told by the smiles on their faces: First, that games are fun, not just endlessly licensable, profitable "products." Games create joy, and joy makes life better. Second, a partnership is born, whether the men are aware of it or not.

Before these two truly partner up, Henk is pure aspiration, and Alexey is pure submission. The pair need each other to temper one another, and present a united front to the Greedy Guses that surround them. Henk and Alexey's partnership is the ultimate reward for all their risk. Forged by illicitly sharing other non-products like dinner, drinks, and conversation, the fledgling friendship between the men is what leads them to improbable success — and survival.

What is a computer?

A spy thriller is nothing without its paperwork, and "Tetris" is nothing without its paperwork that does or does not accurately define the word "computer." Robert Stein (Toby Jones) is the publisher and president of Andromeda Software. Stein thinks he's scored the worldwide rights to Tetris after brokering a deal with the Soviet, state-owned Elektronorgtechnica (ELORG).

Of course, Stein's mistake (or theft) doesn't work out as planned, and while he does have video game rights, arcade rights are still up in the air, and handheld rights might just be anyone's game. Stein is ready to make a mint off royalties after granting the Maxwell family's Mirrorsoft company distribution rights. This is seriously tense stuff, and we haven't even gotten to the contract missing a countersignature yet.

Henk catches a loophole Stein missed (or created) in the original contract with ELORG, which allows for a wide definition of "computer" and would permit Stein to sell worldwide handheld rights for Tetris to anyone he wanted to. Henk points out the loophole and advises ELORG head Nikolai Belikov (Oleg Stefan) that both Stein and the Maxwells are insultingly low-balling ELORG with their offers. Henk does this even though he doesn't know if he'll eventually win over Belikov, but the helpful move later turns the tide for Tetris — and saves Henk, Belikov, and Alexey's skins.

Greed is actually not good

Greed is a major theme that runs through "Tetris" just like a midi version of the game's theme, "Korobeiniki," runs through the original game. Henk's greed is an everyman's greed — a good-natured greed, if you will. There's a fine line between greed and drive, and Henk's friendly, mostly honest nature keeps greed from fully corrupting him. Greed is painted with a more villainous brush when it comes to Robert Maxwell (Roger Allam.) While Henk is a little fish in a shark tank, Robert is the shark from "Jaws."

Robert doesn't need to be scrappy like Henk — he just bribes people, cooks the books, and shreds the proof. All Robert does is win — until he fails spectacularly. When he learns of Stein's slip-up with the rights, Robert tries to steal them for himself, via KGB bribery and standing on ceremony — plus lying about having a million dollars in a week to placate ELORG. If Henk's honesty is what keeps his character clean in "Tetris," Robert's lies make his sinking character stink. Even pressuring Gorbachev to nix the deal Henk brokers with ELORG on behalf of Nintendo can't save him in the end.

My Bloody Valentin

KGB heavy Valentin Trifonov (Igor Grabuzov) is the parallel character in "Tetris" to the greedy, duplicitous Robert Maxwell. Both men are willing to lie to get what they want, and Valentin is willing to also directly destroy lives for it.

Valentin blackmails Henk, threatens to murder Alexey's children, and gets Alexey's family kicked out of their home in the blink of an eye. Valentin does all this as an official agent of the state, and uses his hollow "belief" in what the Soviet state stands for to search for better opportunities for himself, and destroy anyone standing in his way — until, of course, what goes around comes around.

A fairly capitalist greed for money and power is also what drives Valentin to ruin. The sly head of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs manipulates every system and soul available to him to get what he wants, negotiating payment after payment for his services. Valentin's selfish greed kneecaps Soviet success, terrorizes anyone in his orbit, and ultimately gets him thrown in jail by one of his own agents.

Panic and perestroika

Even though everyone in "Tetris" has a selfish stake in the fate of Tetris, the fact that the game could go international at all is culturally significant. Alexey creates Tetris in 1984, and the events of the film hover around that year and 1985 — the same time U.S.S.R. premier Mikhail Gorbachev (Matthew Marsh) starts to shake up the long-suppressed, long-distressed Soviet Union.

Cold War panic up until this point has the Eastern Bloc and the West pitted against each other ideologically, as well as economically. Western countries assume the worst of comrades abroad, and Bloc-heads know Western countries to be selfish and craven lands of excess. Of course, ideology is often a lot easier to understand than reality, and the reality in which Alexey creates Tetris is about to get even more complicated.

In "Tetris," Gorbachev has not yet ushered in perestroika and glasnost — an era of open discussions, some decentralization, and the adoption of some markedly "Western" economic ideas to help improve living conditions in the U.S.S.R. Tetris being open for a very international and lucrative sale — or even trade — is an unprecedented move in unprecedented times. However, hardliners who enjoy the old ways of life and power, like Valentin, won't let times change too easily — they never do. Panic around a Soviet partnership with the West makes the finale of the film (and the real life story of) "Tetris" a truly high-stakes game.

Don't kid a kidder

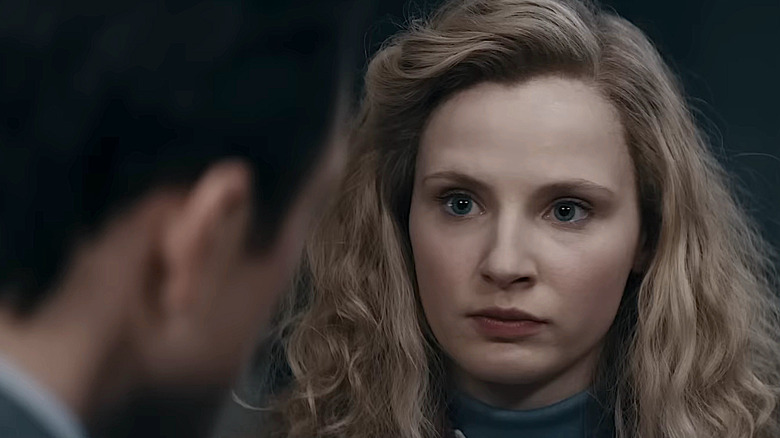

Sasha (Sofia Lebedeva) is so much more than just a friendly face ready to translate for Henk in Moscow — she's a KGB agent with what just might be a heart of tarnished gold. Sasha doesn't have any issue with befriending Henk and helping him translate during his contract hijinks, then trying to seduce him so Valentin can blackmail him off the game board, because she does it all for a cause.

Sasha really does subscribe to the ideals of Communism, and does her dirtiest deeds for the love of country and in service of improving the Soviet Union by protecting it from Western corruption. Of course Sasha is disgusted and heartbroken when she discovers Valentin betrays the greater good of the country for his own personal gain. Sasha is a parallel in some ways to Kevin Maxwell — Robert's son, who likes throw his weight around but has no idea that his true power comes from his father's bribery of the KGB, rather than bottomless wealth and honest business practices.

While Kevin simply steps back from the stink his father creates, Sasha gets her hands dirty — again, for the cause. She brings Valentin in and runs to Gorbachev for assistance, proving that Sasha isn't afraid of the future and the changing face of her home.

Nintendo Switch

Henk gets as far as he can get by himself in Moscow, which isn't half bad. But even though Henk is able to point out on hiw own lies and loopholes in Nikolai Belikov's original contract with Stein, he doesn't have the money — or the correct visa — to make any sort of deal. Henk heads home – but not before bonding with Alexey and Belikov.

Even though Henk wants to turn a profit on Tetris, his love of the game garners him Alexey and Belikov's trust and respect. Henk doesn't try to fleece Belikov — he informs him of Tetris's true valuation, and how badly he's being played by both Stein and the Maxwells. Belikov wants what's best for Russia, and knows the deal with the Maxwells is a bunch of trash. Belikov reaches out to Alexey, and the two help Henk call Mirrorsoft's bluff at great personal risk.

Henk doesn't squander his Russian friends' bravery. Instead, Henk returns to Moscow backed by his own world superpower: Nintendo. Henk now jockeys for a deal with a high-stakes negotiation that, in true '80s spy movie fashion, relies on faxes sent under pain of death. Nintendo wins the deal, which is great for Tetris, and — for a moment, anyway —international relations. It's also a moment in the film that speaks to how much an individual can achieve for themselves and the group when they receive support that isn't hindered by sheer greed or powerlust.

Road blocs

Everything should be gravy for Henk Rogers after he gets Nikolai Belikov to go with Nintendo, right? Nope. Valentin is desperate to change the course of history, and he and his KGB goons give hot pursuit to Alexey and Henk on the streets of Moscow.

The chase is a mash-up of Tetris sound effects and "Grand Theft Auto" driving skills, won by the new partnership of Henk and Alexey. This high-speed, car-door-shaving chase puts even the Super Mario Bros in "Mario Kart" to shame, even if it certainly didn't happen in real life. Still, it thrillingly represents the magnitude of what did. With the Tetris deal, the previously closed-off Soviet Russia opens its doors to new ideas and partnership — even if that door is only open just a crack.

Henk escapes by the skin of his passport, giving Valentin the slip at the airport, and promising he'll send for Alexey. The moment is a reminder that despite the business win, the Iron Curtain could still come crashing down on everything — and Henk could still prove himself to be as selfish as the other business bros in the movie. Will he ditch Alexey, now that he's used him to make the deal of a lifetime?

The golden ticket

Henk gets home to Tokyo in one piece. While he's shaken the KGB's beatdowns and blackmail, he still has a big boss to confront — the consequences of his own actions. Henk has been reckless, and an absentee father and husband to say the least. While part of what makes Henk so winning is Taron Egerton's genuine, heartfelt performance, Henk the character also ultimately follows through on his promises, even if he's a little late.

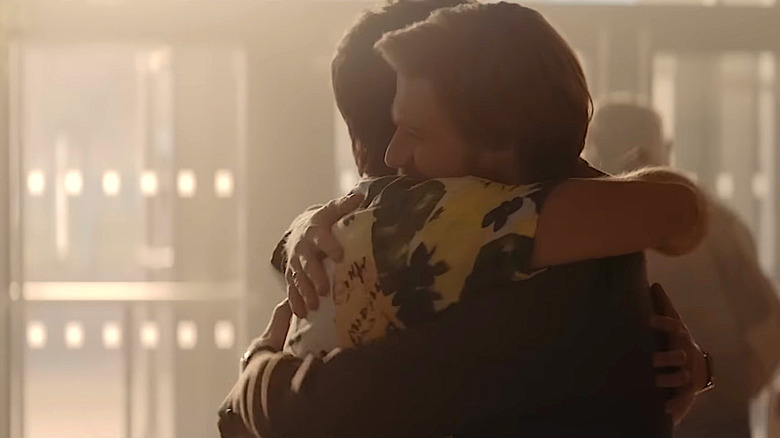

Henk makes good on his promise to his daughter, and his wife Akemi, by recreating the dance recital he missed in their tiny Tokyo apartment. Nintendo's check for $5 million doesn't hurt his relationship with Akemi either, but the sense that Henk seems ready to reconcile and build their business rather than run after the next Tetris wins her over.

Henk also makes good on his promise to Alexey, helping him and his family get out of the U.S.S.R., and into business with him.

The truth of Tetris

"The movie brings my story to the masses and turns what took a year and a half into a two-hour drama on steroids," the real Henk Rogers told USA Today. While the real Henk and Alexey Pajitnov acknowledge the "Hollywood" liberties taken with their story, both agree that the film is based on fact, and that even some exact lines are lifted from real life.

While the depiction of Henk and Alexey's friendship is heartwarming and seemingly accurate, not everyone agrees with the angle the dramatization takes. Robert Stein's granddaughter, Claire Stein, says Stein thought he did have the legitimate rights to Tetris, telling the BBC, "He was not quite understanding there was much more at play when it comes to Russia." There are other details left out of the "Tetris" story that are even stranger than fiction, such as the rumors surrounding "The Tetris Murders" and Robert Maxwell's mysterious death.

In real life, Alexey wasn't impressed by Henk at first, but told Big Issue, "What melted my heart is...that [he] was the first game designer I had ever seen in this world besides myself. So it was a very rare opportunity to look [into the] eyes of a colleague." The genuine connection between the two men, and the fact that they kept working together after the events of the film, puts a human heart into what could have easily been a movie slinging sales slogans about greed masquerading as innovation. Henk and Alexey win the game — and help games win, as well.