That's What's Up: What's Up With X-Force?

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: What's the deal with X-Force? — via email

Buddy, what isn't the deal with X-Force?

No, seriously: despite the fact that it springs from the pretty simple concept of being the X-Men but badass, the idea of X-Force has gone through a lot of changes over the years. At this point, it contains multitudes, and each different interpretation, whether it seems like a return to basics or a wild new direction, fits with the others. And believe it or not, as important as he was, the roots of that big idea go back a lot further than 1991 and the arrival of Rob Liefeld.

X Marks the Start

If you really want to understand X-Force, then you have to understand the comic that it comes from: New Mutants. And if you want to understand that comic, then you have to take a look at the way it came into existence in the first place.

See, Marvel as a company has always been defined by long runs. That makes sense, when you consider that it started with Jack Kirby and Stan Lee doing 100 issues of Fantastic Four, setting the tone that would pretty much carry on for the next six decades. Don't get me wrong, DC has some good long runs that I'll be happy to tell you about some other time, but looking back at Marvel, it seems like that was the place where creators staked claims on books that they'd be on forever. This was the company where Larry Hama wrote 155 issues of G.I. Joe, where Walt Simonson defined Thor over the course of five years, and where Mark Gruenwald was on Captain America for ten. Even stacked up against long runs like that, though, there's one easy pick for the heavyweight champion.

Chris Claremont was on X-Men for 16 years.

Seriously: after Len Wein and Dave Cockrum relaunched the book with Giant Size X-Men #1 in 1975, Claremont took over with the next issue, #94, and stayed there until #279 in 1991. He'd also come back to the franchise more than a few times, but that original tenure is regarded as one of the all-time greatest superhero runs, for good reason. Along with artists and co-plotters like Dave Cockrum, John Byrne, Brent Anderson, and John Romita Jr., Claremont penned classics like the "Dark Phoenix Saga," "Days of Future Past," God Loves, Man Kills, and that one issue where Wolverine tricks Colossus into getting into a bar fight with the Juggernaut. If you can think of a classic X-Men moment, there's like an 80 percent chance that Claremont was at least the one writing dialogue.

New Mutants

The only problem was that Claremont was one of the people who made the X-Men ridiculously popular.

As for why that's a problem, well, Sean Howe goes into detail in the great Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, but the short version is that by the '80s, Marvel wanted to capitalize on the success of the X-Men by launching a spinoff or two. This was going to happen regardless, but if Claremont wanted to maintain control over the characters that his own career had become synonymous with, he'd have to be the one who wrote them. That's why Claremont's there for the launch of Wolverine, although he only stayed on that one for eight issues, and for Excalibur, where he turned in about 30. In 1982, though, the book that spun out of X-Men was New Mutants, which Claremont would write for 54 issues after the oversized special that launched it.

I'm going to be real with you for a second here; "New Mutants" is a terrible name for a superhero team. As the title of a comic, however, it works, largely because the book lived up to it. It wasn't just that the cast was full of new characters, although all of the, uh, new mutants in the book had made their debut in the graphic novel that preceded the series. It quickly became the X-Men book that had as much to do with being new as it did with mutants.

Demon Bears and everything after

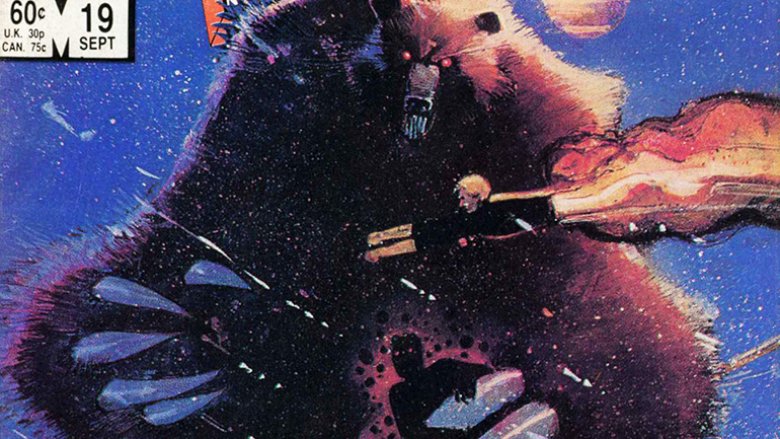

You can see it just by looking at the art style. The books starts off with Bob McLeod and then moves to Sal Buscema — who is exactly the dude you should be thinking of if you see the words "old school Marvel artist" — but starting with the cover of #17, Bill Sienkiewicz shows up and pretty much changes everything.

At the time, Sienkiewicz was still a relatively young artist. He'd arrived at Marvel to do the art for Moon Knight on the recommendation of legendary Batman artist Neal Adams, who told editor-in-chief Jim Shooter that he "had a 19 year-old kid who draws like me" looking for work. That might've been true in 1980, but by the time he got the job on New Mutants, Sienkiewicz had developed a style that was about as far removed from Adams as he could get. His scratchy, nightmarish visuals — which would reach their dizzying high point in books like Elektra: Assassin alongside Frank Miller — helped to define the Demon Bear Saga, the story that many readers consider to be the definitive New Mutants story.

With that, the division between the titles was clear. X-Men was the flagship, but New Mutants was the scout, ready to bring the next big thing to Marvel Comics. And by the dawn of the '90s, there was nothing bigger or more "next" than Rob Liefeld.

Cable and Deadpool

I might just be imagining connections here with the benefit of hindsight, but I really don't think you get to Liefeld on New Mutants without Sienkiewicz paving the way for artists who could push the boundaries of what Marvel Comics could look like. Obviously, he wasn't the only one changing things up — of the seven artists who would later go on to found Image, you'd have to credit at least four of them with bringing some pretty huge changes to the page at Marvel, and that's if you're not feeling particularly charitable. Liefeld, though, was different from the others.

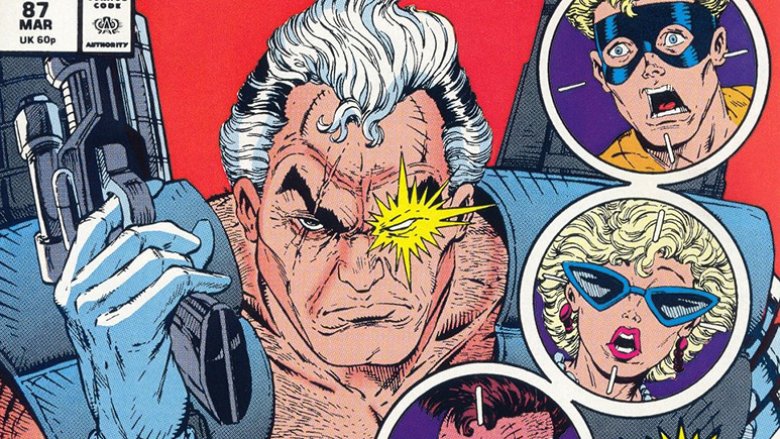

When he arrived on New Mutants with #86, paired with writer Louise Simonson — who had taken the reins from Claremont a few years earlier — the idea was that they'd introduce a character who could serve as a sort of ideological counterpoint to Professor X. He'd be a soldier rather than a pacifist, dedicated more to pragmatism and results than an overriding philosophy, something that would also distinguish him from New Mutants' longest-serving headmaster, a more-or-less reformed Magneto. Also, as Rob has said himself, it didn't surprise him that the most popular X-Man was the guy who had six knives coming out of his hands, so he wanted to make a character who you always knew was carrying his own share of knives. And guns. And everything else.

The result, of course, was Cable, and his arrival was the start of change so big that it wound up being the end of New Mutants. By the next year, Liefeld, with new writer Fabian Nicieza, would create Deadpool, Domino, Shatterstar, and a handful of other characters. So many, in fact, that there were enough cast members, and enough of a new direction, to completely divorce it from the "New Mutants" title — and, not coincidentally, launch a brand new title, poly-bagged with a trading card #1 issue just when the idea of comics as valuable collectibles were hitting their high point.

In April of 1991, New Mutants #100 marked the end of that series. Three months later, X-Force #1 hit the stands in its place.

A force to be reckoned with

Before we get into the content, I should probably mention the numbers. X-Force #1 debuted with record-setting sales of about five million copies. Two months later, in October, Jim Lee and Chris Claremont's X-Men #1 would break that record with six million sold. It's worth noting, though, that X-Men had the benefit of the past two decades, with a classic lineup of characters that everyone already loved. In other words, X-Men had Wolverine and 16 years of goodwill built up from great stories to hit that mark.

X-Force, on the other hand, kept Cannonball and Boom-Boom, but everyone else in the cast was pretty new — Cable had made his first appearance less than two years before X-Force launched. That it could rack up sales that were even in the same stratosphere as X-Men #1 was a pretty huge deal, regardless of the new direction.

But the new direction was there. As the title implies, X-Force was set in a superhero universe, but it wasn't really about a superhero team. It was about a strike force. It was militarized mutants taking on a different sort of threat. If you go back and read that first issue, it really does set the tone well — it's about X-Force taking on a terrorist group, and on page seven, Shatterstar chops a dude's hand off, all while dealing with standard-issue superhero stuff like clones and time travel. It's a pretty big departure, even from X-Men #1, which opens with the X-Men doing a training exercise with robots and Magneto chilling out in space in footie pajamas. That's not a judgment call on either of those comics — I can assure you that I love that '90s X-Men run to pieces, and I think my own work at Marvel will back that up — but it does represent the difference in those stories.

After Liefeld's departure for Image, though, X-Force struggled to find a real voice. The idea of militarized mutants had found a more permanent home in X-Factor, which had shifted from being a book about the original X-Men reuniting for new adventures into the story of a government-sponsored superhero team. Meanwhile, every new creative team brought onto X-Force seemed to have its own idea of what the book should be, including new lineups and bases of operations every couple of years. The closest it got to that original idea was when Warren Ellis, Ian Edgington, and Whilce Portacio — one of the seven artists who had left to form Image years earlier — recast the team as a black ops strike force working for a British secret agent who would go on to lead another team to fight off Dracula when he invaded England from his moon-base. I honestly think that only a few years later, that new direction would've been a hit, but at the time, it didn't work.

And then things got weird.

X-Force Reborn

In X-Force #115, most of the existing cast, including Cannonball and Warpath, appeared to die in an explosion. In the next issue, an entirely new team debuted courtesy of Peter Milligan and Mike Allred, with the hook being that they they were essentially reality show superheroes, and also mostly terrible people looking to get famous off their somewhat unfortunate mutations.

In its own way, putting Mike Allred on X-Force was as big a change as putting Liefeld on New Mutants. Allred was hardly the rookie superstar Liefeld had been in 1991 — he'd actually been a well-respected indie cartoonist for years with a long-running creator-owned book called Madman, and had even done occasional mainstream work on books like Sandman for DC's Vertigo imprint — but putting him on the book that still existed in a lot of people's minds as Liefeld's paramilitary mutant strike force was downright shocking.

Milligan's arrival was less surprising, but still pretty intriguing. He'd done plenty of superhero work before, including a couple of X-Men stories, but he always approached superheroes from an interestingly bizarre direction. If you need an example, look no further than Dark Knight, Dark City. It's one of my all-time favorite Batman stories, and arguably the single best Riddler story ever, but it's also a comic where a demon that was summoned into Gotham City by Thomas Jefferson in the 18th century possesses the Riddler and embarks on a scheme to make Batman accidentally perform satanic rites like bathing in blood (by detonating plastic explosives in a blood bank) and dancing before a goat (by shooting at him with a flamethrower while a goat just sort of happens to be there). It is buck wild, and the weirdest thing about it might be that it would wind up informing a whole lot of 21st-century Batman stories, but it's a pretty good example of the kind of sensibilities that Milligan could bring to superheroes.

Put those two creators together, and it was lightning in a bottle, with some truly strange results.

X-Statix

I mentioned earlier that the characters in Milligan and Allred's X-Force didn't have the kind of mutations that you might expect from superheroes, and that's true. The most conventional were probably U-Go-Girl, a long-distance teleporter whose abilities put her to sleep every time she used them, and the Anarchist, who had acidic sweat. The rest of the characters were more in line with their leader, Mr. Sensitive, whose over-developed senses made it incredibly painful for him to even exist outside of a special suit designed by Professor X.

And then there was Doop, the breakout star of the book. If you've never read it, imagine a lumpy green potato with eyes who could float and spoke only in a language that was represented on the page with a specialized font that was never translated in the comics themselves. He's canonically Wolverine's best friend, and once fought Thor with a broken beer bottle. Needless to say, he was the breakout star of the book, and wound up making it to the main roster of the X-Men on more than one occasion.

There was also Dead Girl, whose power was being dead, but she wasn't exactly alone in that regard. Milligan and Allred's X-Force had an incredibly high mortality rate. All but two of the characters introduced in X-Force #116 died in that same issue, and the rest of the cast (including Doop, who would eventually return) was killed off when the series ended. Please note that this is not the strangest thing to happen over the course of this comic.

Back From the Dead

The actual strangest thing happened in X-Statix #13. If you're wondering about the name change, that's a little weird too. At the time, Marvel was making what appeared to be an attempt to distance themselves from some of Liefeld's creations. Deadpool and Cable were temporarily renamed to "Agent X" and "Soldier X," respectively — and if you think it's weird looking back from today that there was a time when Deadpool wasn't Deadpool, you should see how that story unraveled itself in continuity — and Milligan and Allred's X-Force ended with #129 and was relaunched as X-Statix.

And then in 2003, they tried to add Princess Diana to the team.

If you've been paying attention, you might've already noticed that there are a couple of problems with this. First, Diana, Princess of Wales, was a real person and not a Marvel Comics character. Second, Diana died in 1997. Third, and probably most importantly, six years wasn't really enough time for the tragic death of someone called "the people's princess" to become something we could comfortably poke fun of in an X-Men comic.

X-Statix #13, which bore the title "Di Another Day," was announced as featuring Diana, and Allred drew plenty of art that depicted the late princess fighting alongside the team. Unsurprisingly, there was an immediate backlash, and Marvel backed down from that particular element. The story and the character did make it to print, though — Allred just drew a new brunette hairstyle for the renamed Henrietta Hunter that just made her look like Diana in a wig — but she was recast as a pop star instead.

The Uncanny X-Force

All that leads to the team's most recent incarnation, and as weird as it might sound, it exists at the nexus of all of those ideas. Like the original X-Force, they were a strike team dealing in covert ops that required extreme solutions. Like the post-Liefeld lineups, there were well-known X-Men characters like Wolverine, Psylocke, and Archangel involved, with a couple weirdos like Deadpool and Fantomex. And while it never got to the extremes of Henrietta Hunter or the fame-hungry aesthetic of the X-Statix, they dealt with some truly bizarre stuff. There was a teenage clone of Apocalypse in that book, and a genetic engineering factory that had been shrunk down to the size of a softball.

And that's X-Force. A bunch of different takes on the same high concept: new ideas, new directions, and an extreme version of the X-Men for whatever definition of "extreme" is most prevalent at the time.

It might seem complicated, but it's actually pretty simple. I mean, when we created a retro X-Force team in X-Men '92, Chad Bowers and I just stocked it with everyone who has a mutant power but uses a gun or a sword instead. It just felt right.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up.