Facts From The Dark Heart Of Deliverance

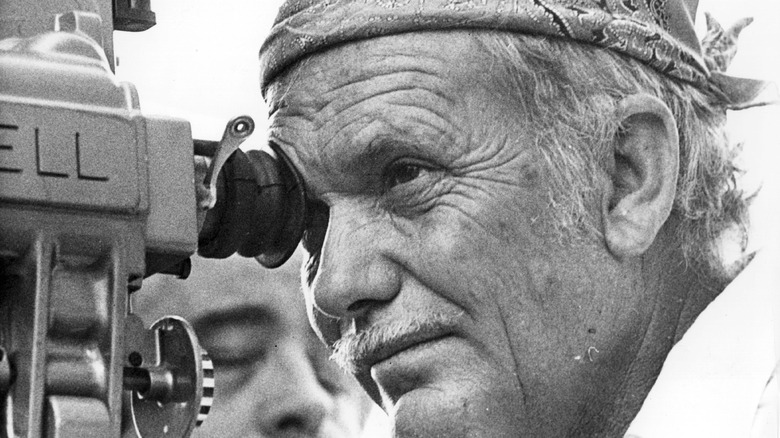

Heading downriver to get back to nature and enjoy a little bit of male bonding, fishing, and a few brewskis with the guys might sound like a great way to spend the weekend. But that will change as soon as you watch "Deliverance." Based on James Dickey's book, director John Boorman's 1972 classic about heading into the great outdoors in pursuit of lost notions of manhood and the simple life is a cautionary tale that has lost none of its visceral power.

The fictional Cahulawassee River where Lewis, Drew, Bobby, and Ed take their doomed canoe trip is much like the river in Joseph Conrad's novel "Heart of Darkness" and Francis Ford Coppola's "Apocalypse Now." It's symbolic of how civilization and all its niceties can be washed away almost overnight by a subconscious surge of savagery and primal fear.

Ironically, it's not the sadistic locals with their bad teeth and predatory smiles that are the biggest threat to the outdoor pursuit enthusiasts. It's their own prejudices and insecurities and the indifferent and unforgiving face of Mother Nature that prove their real undoing. "Deliverance" is a thrilling white-water rapid ride into the dark heart of the American wilderness and the primal subconscious. Here are some interesting facts about this harrowing classic.

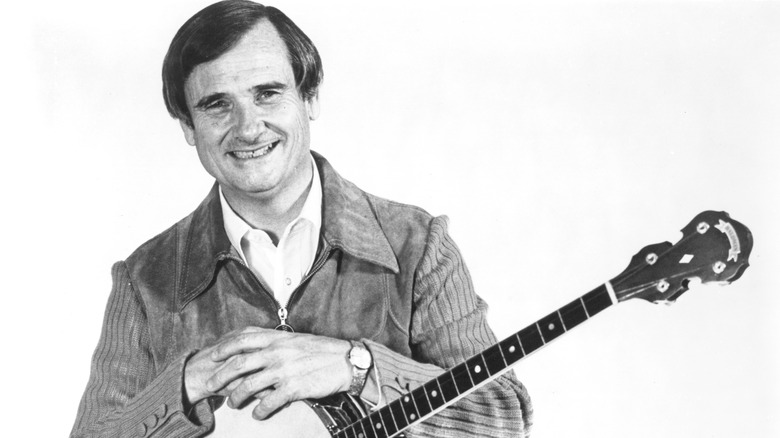

Banjo boy couldn't play his instrument

Aside from the horrific scene where Bobby is made to squeal like a pig, "Deliverance" is universally associated with banjos. The scene where Drew Ballinger (Ronny Cox) begins an impromptu jam with a curious-looking banjo player named Lonnie at a gas station is like the calm before the storm. On repeated viewing, it's almost like a weird kind of warning that things are about to go pear-shaped and fast.

The part of Lonnie went to a boy from Clayton named Billy Redden, who couldn't actually play the instrument he immortalized in the film. According to Garden & Gun, an early draft of "Deliverance" described Lonnie as "probably a half-wit, likely from a family inbred to the point of imbecility." Casting director Lynn Stalmaster explained that he asked a Clayton local where he could find a "very odd-looking boy" for the role. He was directed to a local grammar school. "Suddenly, this boy appeared," Stalmaster recalled. "He looked exactly like the kind of youngster John Boorman wanted."

The director told The Guardian, "We needed someone who looked inbred for the banjo player. Redden looked extraordinary, but couldn't play. So we made a shirt with an extra sleeve in it, and a musician crouched behind doing the fretwork as Redden strummed." Boorman added, "There was a lot written afterward about how Deliverance libeled mountain people. But the locals were thrilled with the film."

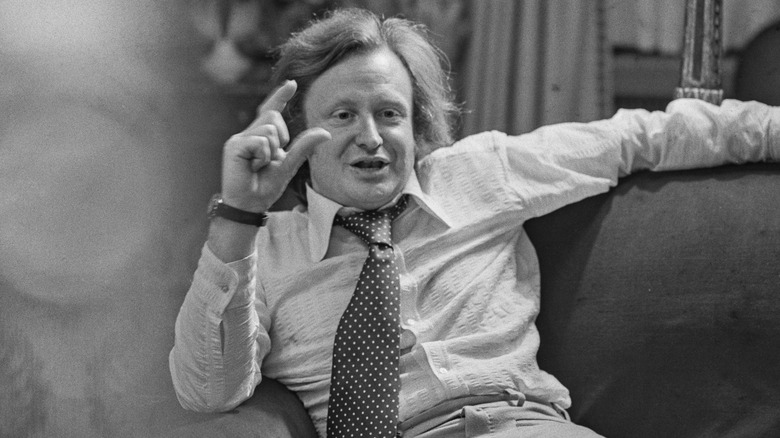

The composer of Dueling Banjos sued

"Dueling Banjos" is an instantly recognizable piece of music that manages to simultaneously inspire joy and — due to its connotations with the film — invoke a strange sense of unease. Yet the man responsible for its composition ended up suing Warner Bros. because they used the tune without his permission and failed to acknowledge him as its original composer. Originally entitled "Feudin' Banjos," the song was composed in 1955 by Arthur "Guitar Boogie" Smith. According to some it was inspired by a 17th-century jig, "In the Mountains." Upon hearing the Dillards' 1960s version of "Feudin' Banjos," "Deliverance" novelist and screenwriter James Dickey recommended it to director John Boorman for inclusion in the film adaptation.

New York City folk musicians Steve Mandell and Eric Weissberg recorded their version of Smith's song two years before "Deliverance" and renamed it "Dueling Banjos." In the wake of the film's success, the duo hit the touring and TV circuit as a band named, wait for it, "Deliverance." The tune was also used in Toyota and Mitsubishi commercials. Meanwhile, composer Arthur Smith had opened legal proceedings against Warner Bros. for their failure to credit or reimburse him financially. After being offered a paltry $15,000 to go away, Smith dug his heels in, took them to court, and eventually won all ownership and royalties. Now put that in your banjo and play it.

Rabun County locals believe Deliverance portrayed them as deviant, redneck hillbillies

Near the end of "Deliverance," there's a touching scene in which Bobby (Ned Beatty) and Ed (Jon Voight) are offered some much-needed warmth and hospitality at the table of a family of chatty and friendly locals. After the hell and horror they have endured in the wilderness, the domestic setting and the kindness of strangers prove too much for Ed who breaks down in tears. Of course, that's not this scene viewers tend to associate with the film's portrayal of the inhabitants of Rabun County. It's the one where Ed is tied to a tree, held at gunpoint by a toothless pervert, and forced to watch as Bobby is demeaned as a pig and sexually assaulted. It's little wonder that many in this corner of Georgia were concerned about the damage "Deliverance" might have on their collective reputation.

On the 40th anniversary of "Deliverance," Rabun County Commissioner Stanley "Butch" Darnell told CNN, "We were portrayed as ignorant, backward, scary, deviant, redneck hillbillies. That stuck with us through all these years and in fact, that was probably furthest from the truth. These people up here are a very caring, lovely people." Darnell added, "There are lots of people in Rabun County that would be just as happy if they never heard the word Deliverance again." But Billy Redden, who played Lonnie the banjo boy and still lives in the area, begs to differ. He explained that people shouldn't be bothered by things that happen in the film. "I think they just need to start realizing that it's just a movie. It's not like it's real."

Screenwriter James Dickey claimed everything in Deliverance happened to him

In Garden & Gun, writer Pat Conroy describes "Deliverance" novelist and screenwriter James Dickey as "the kind of man who made Ernest Hemingway look like a florist from the Midwest." Director John Boorman, meanwhile, recalled that the first time he met Dickey, the native Georgian said, "I'm going to tell you something I've never told a living soul, and I want you to promise not to mention it to anybody: Everything in the book happened to me." Boorman couldn't wait to tell associate producer Charles Orme, who replied, "Yes, he told me the same thing."

Dickey can actually be seen in a cameo as Sheriff Bullard. He delivers one of the film's most memorable lines: "I'd kinda like this place to die peaceful." Film editor Tom Priestly praised this particular piece of dialogue, saying, "I think [it's] the best in the whole film. It says so much. He knows there's some strange business going on — let's not stir it up." Pat Conroy recalled an early screening in Atlanta, "When Jim came on the screen as the sheriff, somebody in the back of the theater jumped up and began applauding," Conroy said. "It was Jim. Applauding himself. He was clapping and yelling. 'Nice job!' I thought. That's how a poet acts."

Deliverance kickstarted the lucrative white-water rafting industry in the area

The Cahulawassee River (in reality the Chattooga River) rolls and coils its way through "Deliverance" like an unknowable and all-mighty serpent. If not for their desire to ride its currents one last time before its vitality and majesty is drowned by the proposed dam, Ed, Lewis, Bobby, and Drew wouldn't have been carried to a place where civilization ends and the wilderness begins. Yet any trip worth taking is about the journey and not the destination, and the white-water rapid rides in "Deliverance" make for some pretty breathtaking and exhilarating viewing. According to Larry Mashburn, owner of Georgia-based rafting company Southeastern Expeditions, "Deliverance" was responsible for popularizing the white-water rafting industry in the Southeastern United States.

At the beginning of "Deliverance," Lewis asks from off-camera, "You want to talk about the vanishing wilderness?" Apparently plenty of people did, and those people couldn't wait to make a trip to Rabun County, hop on a rapid, and feel the rush. In 2012 the Rabun County Convention and Visitor's Bureau reported that over a quarter million people visited the area yearly to travel down the same river "Deliverance" made famous. Real estate agent Debra Butler told CNN that millions in revenue from tourism helped bring had made Rabun County a very desirable place to live. "Once people come to Rabun County, they don't want to leave," explained Butler, who added, "This is a lifestyle that you have here. It's a way of life. 'Deliverance' depicts a backwoods, inbred kind of community. That is not Rabun County."

Sam Peckinpah nearly directed Deliverance

Before John Boorman came on board and directed the hell out of "Deliverance," novelist and screenwriter James Dickey had Sam Peckinpah in his sights to direct the movie. According to Salon, during a meeting between the writer and the director, Peckinpah told Dickey, "You and I are doing the same thing, me with my images up on the screen and you with your words on the page. We're trying to give them images that they can't forget."

Perhaps wary of the controversy that seemed to follow in the trail of the volatile director and his reputation of going way over budget on 1970's "The Ballad of Cable Hogue," Warner Bros. opted to go with Boorman in the director's chair. Boorman told Garden & Gun, "I had made 'Hell in the Pacific' with Lee Marvin and Toshiro Mifune under very difficult circumstances in the South Seas. We lived on a ship anchored off this island where we shot it, so I think Warner Bros. felt I was the kind of man to take on a very physical picture."

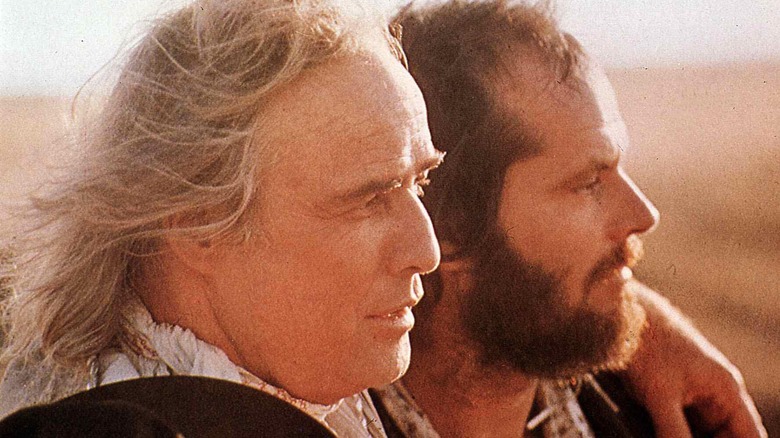

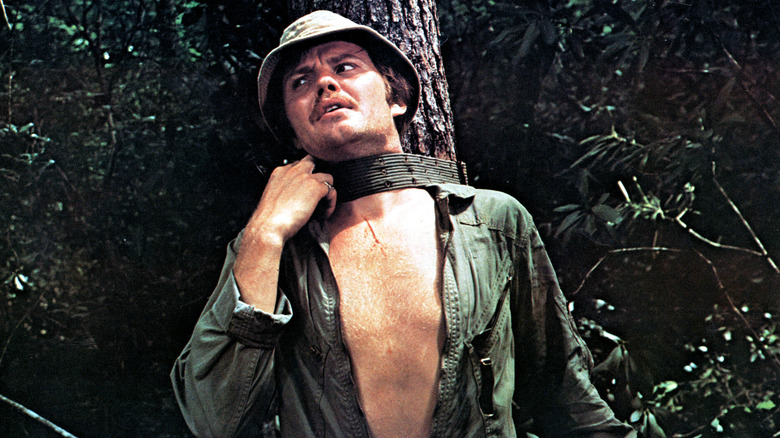

Jack Nicholson and Marlon Brando could have played Ed and Lewis

Lee Marvin and Gene Hackman were discussed as potential candidates to play Ed and Lewis in "Deliverance," but it was Jack Nicholson and Marlon Brando who very nearly took the roles that Jon Voight and Burt Reynolds eventually made famous. John Boorman told Garden & Gun, "Warner Bros. wanted two major starts, so I went to Jack Nicholson (to play Ed). He agreed to do it and asked, 'Who will you get to play Lewis?' I said, 'I don't really know yet.' He said, 'What about Brando.'" Boorman recalled paying Brando a visit during which the Hollywood legend eventually agreed to appear in the film. Because Brando didn't have an agent, when Boorman asked him his fee he simply replied, "I'll take the same as you pay Jack!"

When Boorman asked Nicholson's agent what his fee would be, he was given the grossly exaggerated figure of half a million dollars. Boorman revealed, "Nicholson had never got more than $75,000." When he told studio head Ted Ashley of Nicholson's fee, Ashley "almost went through the roof." Yet that was nothing compared to his reaction when he heard Brando wanted the same. Ashley exclaimed, "Brando? Oh, God. He doesn't mean anything anymore — he's box-office poison. I'd be laughed out of this town if I paid half a million for Brando." Deciding that paying through the nose for established stars wasn't the right tack to follow, Ashley advised, "Make it for a price, go with unknowns, and let's see what happens."

Deliverance was a huge influence on the hillbilly and backwoods horror sub-genres

In reality, a couple of days in the wilderness will usually amount to little more than a gruesome hangover, a lingering cold, and a newfound appreciation of the comforts of civilization. In the movies, though, when a group of friends set off on a jolly expedition into the great outdoors with high ideals of getting back to nature and finding their primal selves, it nearly always ends badly. On the trail of "Deliverance," there was a raft of films that appeared to suggest the world outside of the city was a lawless and primordial swamp populated by people with bad teeth, terrible haircuts, guttural accents, and a passion for hunting, torturing, and killing anyone incapable of wrestling an alligator or skinning a grizzly.

"Deliverance" played a pivotal role in the Southern Gothic genre which depicts "mountain people" as the alien other, and it had a huge influence on hillbilly and backwoods horror films such as "Southern Comfort," "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre," and "The Hills Have Eyes." Southern Gothic expert Dr. Bernice Murphy told BBC Culture, "The Southern Gothic generally depicts the region as a place that has been left behind by the rest of the United States, and which is dangerously in thrall to the self-aggrandizing myths of the Old South. 'Deliverance' is a superb example of the Southern Gothic meets backwoods horror narrative: the Georgia wilderness is here depicted as a place set apart from the rest of the world."

All four leads were involved in the white-water rafting scenes

Although all four leading men in "Deliverance" had a stunt double to carry the can as they approached the business end of things, John Boorman told the BBC that Burt Reynolds, Jon Voight, Ned Beatty, and Ronny Cox all stuck it out with gusto when it came to the white-water rafting scenes. "I had four good guys, who were very brave. I had a man ready to rescue them all the time and they thankfully managed to stay alive," explained Boorman.

After Beatty very nearly flipped his canoe and drowned he remembered thinking, "How will John finish the film without me if I drown?" Before musing, "That f***er will find a way to do it without me."

Boorman recalls that the inherent threat that the rafting scenes posed worked wonders on keeping things real and helping the actors claw a little deeper into their characters. In an interview with IndieWire, Cox revealed, "John canoed the whole river himself. He never asked to do anything that he hadn't done himself." Cox went on to explain just what he learned about rafting. "The places that are really the most dangerous never look dangerous. You can have the most horrendous-looking set of rapids and often times they are a piece of cake. There are other places that look pretty innocuous, and these are invariably the places where you get in trouble."

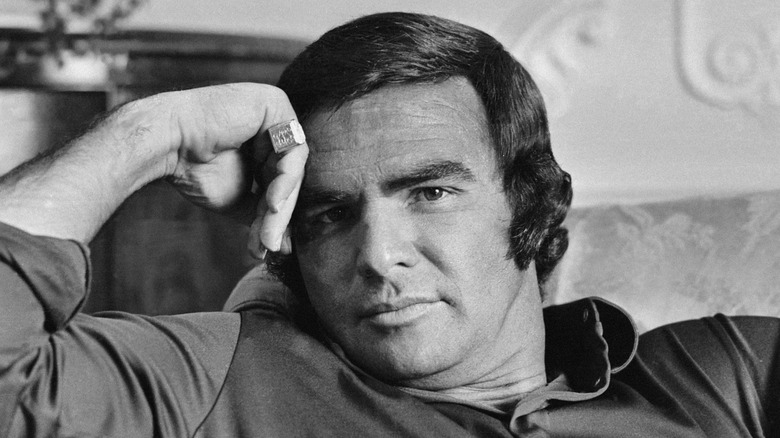

Burt Reynolds and Jon Voight faced injury and danger

It wasn't just near drownings that made "Deliverance" the sort of movie set that would send a health and safety official into an incandescent rage. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Burt Reynolds revealed that the film included the most memorable stunt of his career — one that ended with a cracked tailbone. "They had a dummy go over the falls and I said, 'I can go over the falls' ... [Boorman] said, 'Are you sure?' I said, 'Absolutely,'" he recalled.

"I heard this sound – I dream sometimes of the water coming – I looked around and there was a tidal wave coming at me," Reynolds continued. "I went over the falls and the first thing that happened, was I hit a rock and cracked my tailbone, and to this day it hurts."

Jon Voight also carries his own war wounds from filming "Deliverance." The actor told The Guardian that he almost got killed during the cliff-climbing scene. "I was about 10 feet up on the face, which was slippy and almost perpendicular. I told the two grips below me, 'If I start to fall off, I'm going to push off the rocks. And you'll catch me.' I started to slip, called out and one of them caught me. There was a sharp rock inches from my head."

The director and writer got into a fistfight on set

If near drownings and fatal falls weren't enough, the set of "Deliverance" was also plagued by the testosterone-fuelled antics of two of its alpha males — director John Boorman and novelist/screenwriter James Dickey. According to the Los Angeles Times, Dickey wasn't a fan of Boorman tinkering with his vision for how "Deliverance" should be captured on celluloid, and their constant disagreements came to a head one day after the writer had been on a particularly intense drinking spree. Deciding artistic differences were best settled with fists, Dickey took a swing at Boorman and cracked four of the director's teeth.

The writer was banished from the set in the immediate aftermath, and although Jon Voight explained that Dickey was upset by what he considered being stabbed in the back, Boorman's vision was anything but misguided. "It's very difficult to question the judgment of Boorman," the actor said. "It's all there on the screen. He edited the film on the set. He knew every shot and what it would like, and he knew when he had it and moved on."

Ronny Cox told Garden & Gun that Dickey believed Boorman's intention with the film was to steal his thunder and ruin his credibility. "Jim was a type-A male who wanted everything. He really thought he was going to go down there to Clayton and direct the movie and do everything else," explained Cox.

Burt Reynolds believes Deliverance forced a lot of men to confront the true horror of rape

Over half a century after its release, the rape scene in "Deliverance" remains one of the most disturbing and harrowing moments in cinematic history. It comes pretty much out of nowhere, and although short, appears to last an eternity. In the film's opening shot of the Cahulawassee River, we hear the voice of Burt Reynold's character off-screen talking about the proposed plan to build a dam across the river, and he rants about the "rape" of the landscape. It's a grim foreboding of events to come, but also an indication of how casually men use the word rape as a throwaway term.

In an interview with The Huffington Post, Reynolds explained he believed women have a better understanding of "Deliverance" because they never underestimate the terrible impact and threat of rape, and it's something that society has taught them to be constantly vigilant of. Alternately, it's not a danger that's on most men's radar, which can lead to a collective lack of empathy for victims of sexual assault. "For so many years men threw the word rape around and never thought about what they were saying," Reynolds said. "And I think the picture makes men think about something very important, that we understand the pain and embarrassment and the change of people's lives."

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Deliverance was shot entirely in sequence

As a rule, movies don't tend to be shot chronologically. Filmmaking is a bit like a jigsaw with no beginning or end, but whose final picture is only revealed when every piece falls into place. "Deliverance," though, was the rare movie shot entirely in sequence. As a newcomer to the world of movies, "Deliverance" was Ronny Cox's first taste of acting outside of theatre. "Both Ned Beatty and I thought that was how films were made," he told IndieWire. "Burt came to us and said, 'You don't know how lucky you are.'"

Cox explained that because it was largely set on a river and "went from A to point B," the production didn't use any location more than once, so it lent itself well to a chronological shoot. "The easy rapids were at the beginning of the film and the rapids got harder and harder as we go through the film," the actor continued. "So by the time we got to the really hard rapids, we had had canoe practice and had been on the water for five or six weeks of six or seven, eight hours a day. So by that time, we were all really good canoers. It made a lot of sense to shoot that film in sequence."

James Dickey refused to address the actors by their real names

To screenwriter James Dickey, Burt Reynolds, Jon Voight, Ned Beatty, and Ronny Cox were simply Lewis, Ed, Bobby, and Drew. The man Reynolds described to The Huffington Post as a bigger-than-life poet and alcoholic would refuse to address the actors by their real names and instead referred to them by the names of their characters. "He owned those characters," Cox said. "He owned Lewis. He didn't own Burt. He would come in with his cronies and say, 'Drew! Come over here and do that scene!' And want you to play that scene for his cronies."

Voight added that Dickey made a great sheriff in the movie and praised his presence. The actor told Garden & Gun, "He had great confidence in his persona — more than I have. I'm a person who questions everything, myself most of all. Dickey didn't have that gene."

Reynolds recalled that he was in the bar with Dickey one evening after a day's filming when the writer kept calling him Lewis. When Reynolds refused to answer, he got right in his face and said, "I'm talking to you, Lewis!" Reynolds replied, "You're not talking to me, Mr. Dickey, because my name is Burt and Lewis works tomorrow between seven and five." Dickey replied, "That's exactly what Lewis would have said."

Burt Reynolds believes his nude photo shoot ruined Deliverance's Oscar chances

Although "Deliverance" was nominated for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Film Editing at the 1973 Academy Awards, the film's trophy cabinet remains empty. Francis Ford Coppola's "The Godfather" won Best Picture, and Bob Fosse took the directing honors for "Cabaret." Burt Reynolds believes the reason that the film's river might have run dry at that year's Oscars was because of his saucy pin-up shoot for Cosmopolitan. Riding on the wave of success that "Deliverance" delivered, Reynolds famously bared all on a bearskin rug in 1972.

The folks at the Awards Academy may not have been so enamored of Reynolds in the raw, and the actor confessed in an interview with Piers Morgan Life Stories that he thought this could have damaged the movie's chances. "I really can't look at it. I'm very embarrassed by it," he said. "I thought it cost some actors in 'Deliverance' an Academy Award ... Jon Voight was incredible. I think it hurt Jon. I think it hurt Ned Beatty. He certainly deserved an Oscar nomination. I think it hurt me too. It was just the wrong timing."

Brian De Palma's Carrie ending is a tribute to Deliverance

The final scene of "Deliverance" sees Ed lost in a nightmare where an unidentified hand rises from the water in mute and eternal accusation of his and his friends' actions upon the river. He awakes to the sound of banjos and his wife telling him to go back to sleep. It's one of those ambiguous endings that announces in no uncertain terms that the horror will never be over and the devil always collects — today, tomorrow, or many years from now. The imagery of the dead hand rising out of the depths and being controlled by some unknown agency is an extremely powerful one that Brian De Palma would steal a few years later for the ending of his 1976 adaptation of Stephen King's "Carrie."

The scene in question involves survivor Sue visiting the remains of Carrie's burned-down house to lay some flowers. The tranquility of the scene is suddenly sliced in two by Carrie's bloody arm reaching up from beneath the ground, either in a desperate plea for help or to drag her friend back with her to the bowels of hell. It transpires that it's all a nightmare that Sue wakes from, but one you just know she'll be forever haunted by. Although the scene is often credited with setting the horror movie trend of sending the audience out with one last jump scare, it was actually an homage to what "Deliverance" had done before it. De Palma was merely paying tribute to a film that blazed a trail as winding, long, and fiercely engaging as the Cahulawassee River.