That's What's Up: The True History Of Infinity War

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: I've been thinking about Infinity War. How exactly did we get to this point? — via email

Okay, there are a couple of different answers to this question. If you want to know how we got there in the context of the movies, then I'd suggest watching, say, Iron Man 3, all three Captain Americas, both Guardians of the Galaxy movies, Thor: Ragnarok, Black Panther, and Spider-Man: Homecoming. Believe me, they're not going to be difficult to find, and they'll probably get you caught up enough so that you'll know what's going on when people start showing up and talking about this giant purple dude who wants to kill the universe.

If, however, you're asking about how we got to the point where the biggest movie in the world is about 40 superheroes fighting a dude with a power glove made out of magic stones, that answer's a little more complicated. When you get right down to it, though, it was inevitable that we'd get here. We've been building up to it for the entire history of superheroes as a genre.

If one's good, a thousand are better

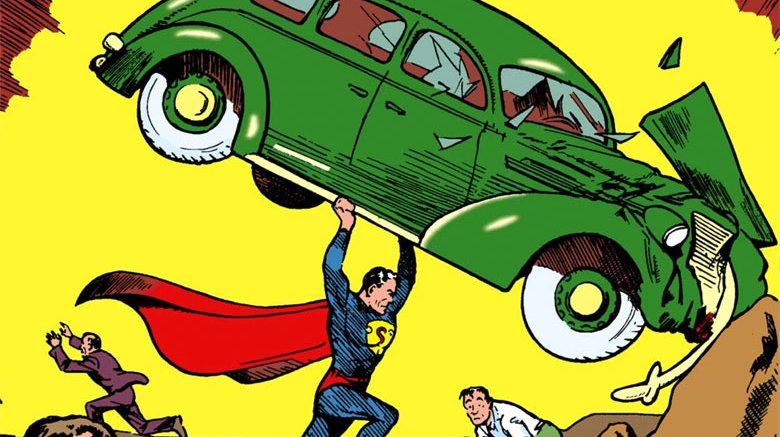

I'm not kidding about going all the way back to the beginning on this one. See, after Superman debuted in 1938, he didn't just kick off the genre that would grow to largely define comic books for the rest of the century. He made money, and although most of it was for National Publishing and not Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, it was a lot of money. This was an entirely new kind of character in a purely visual medium that was relatively cheap to produce for the publishers, and permanent for the consumers, unlike movies, radio, and the brand new upstart that was television. Those were all fleeting, almost ethereal experiences, and with movies, if you wanted to enjoy them again, you had to pay for it again, too.

The tradeoff to having static images on the page was that you could re-read them as much as you wanted, and see sights like a man in cape lifting a car over his head, or catch a glimpse of someone punching Hitler right in the mouth. You could even pass them around to other people — in the '40s and '50s, publishers would often estimate that their actual readership was three or four times bigger than the number of copies they were selling, because each issue would pass through that many readers on average. Honestly, I'm pretty sure that's why superheroes developed the kind of obsessive, detail-oriented fans that they did — if you start off as the a popular medium that's almost scientifically crafted to be read over and over and shared with your friends, you're going to wind up noticing all the small stuff and having conversations about contradictions and continuity.

The Golden Age Boom sets the stage

But that's a subject for another time. All of this is to say that with that huge success came a truly staggering amount of imitators, knockoffs, and other new superheroes, all trying to be the next Superman and get their share of that incredibly lucrative new market. Most of them were extremely bad — Siegel and Shuster had an advantage that a lot of other Golden Age creators didn't, in that they were actually good at making comics. Then again, that's not a problem confined to the '40s.

Every time a boom period brings a flood of new creators and ideas comics, from the black-and-white indie stuff of the '80s to the dawn of webcomics in the early 2000s, you're going to get a lot of terrible stuff. Most of it doesn't last, but in the case of Golden Age comics, it's easy to see why the ones that stuck around were, well, good enough to stick around. People like Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, Otto Binder, C.C. Beck, and Jack Cole were all creating great stories, and even the people who weren't had some pretty amazing high concepts making their way onto the page. Ask me about Nightmare and Sleepy sometime if you want to know how great those ideas could be when nobody knew the rules of comics yet.

While many of those characters were cropping up from other publishers who wanted to get their version of Superman — most famously Fawcett, whose Shazam-powered Captain Marvel managed to outsell the Man of Steel for most of his original run by improving on those basic ideas — a lot of them came from National, the company that wound up with Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, along with plenty of other lower-tier heroes.

With that many running around, it was only a matter of time before someone figured out that you should probably put them in the same story.

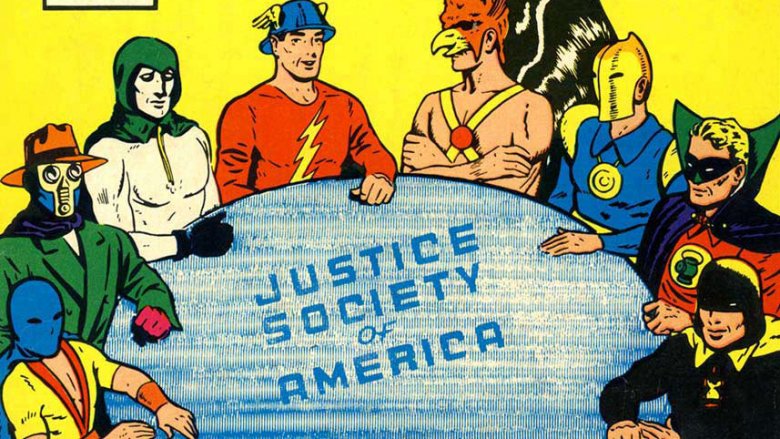

All Star Comics #3: It begins

That's what makes All Star Comics #3 such a big deal. That's the comic that introduced the Justice Society of America, the first super-team. It wasn't just that it was an ensemble cast, but that it was a team made up of established solo characters that had their own solo adventures outside of the team.

Like a lot of later teams, it was built on the pretty commercial idea of getting readers who were interested in one character to care about another. If you liked Wonder Woman or the Flash and picked up All Star to follow their adventures, maybe you'd get into Green Lantern or the Atom, too, and start reading their comics as well. This, incidentally, is how Marvel and DC would attempt to get people to care about Hawkeye and Aquaman, respectively, for decades.

The weird twist is that back then, there was this idea that characters like Batman and Superman, unquestionably the most popular characters in DC's lineup, weren't considered a necessary part of the team. You'd think they would've been the first characters thrown in there — even in 1940, there were a lot more people who cared about Batman than Hourman the Spectre — but I think the idea was that Superman and Batman were just too big to be there. They were, after all, meant to be unique, the only ones of their kind in their own little worlds of Metropolis and Gotham City.

That idea seems to be borne out by the way they appeared in World's Finest Comics. From the very beginning, Superman and Batman — and Robin, the often overlooked third part of that particular heroic triangle — appeared in every issue, and would hang out on the covers, usually playing basketball or goofing off with each other. They didn't actually start teaming up in the stories, however, until World's Finest #71, a full 13 years after that comic started.

Teams and Team-Ups

But here's the thing: mass media actually got there first.

In 1945, nine years before Superman and Batman would team up in the comics, Batman and Superman would fight crime together on the Adventures of Superman radio show. Again, this was commercially motivated — that series was hugely popular, and since reruns were unheard of in those days, Batman and Robin would occasionally take over when Superman actor Bud Collyer needed a break. That's really where it starts, but even with that, comics had something that a radio show didn't. They had a shared universe.

Eventually, though, comics figured it out. In 1960, DC reformed the Justice Society for a new generation, giving it the modern name "Justice League" because, and this is true, they figured kids would prefer a league to a society because of major league baseball. This time, they threw in all the big-name characters who were holding down their own titles, and used them to increase the profile of lower-tier characters who weren't. The big one, and this isn't just me clowning on him this time, was Aquaman — he wouldn't have his name on the cover until 1962, when he took over Showcase — but they also boosted second-stringers like Green Arrow, too.

These might not seem like the steps that would be contributing directly to Infinity War, but trust me. We're getting there, and the '60s brought two more very important elements. That's when comics invented... the Event.

Inventing the Event

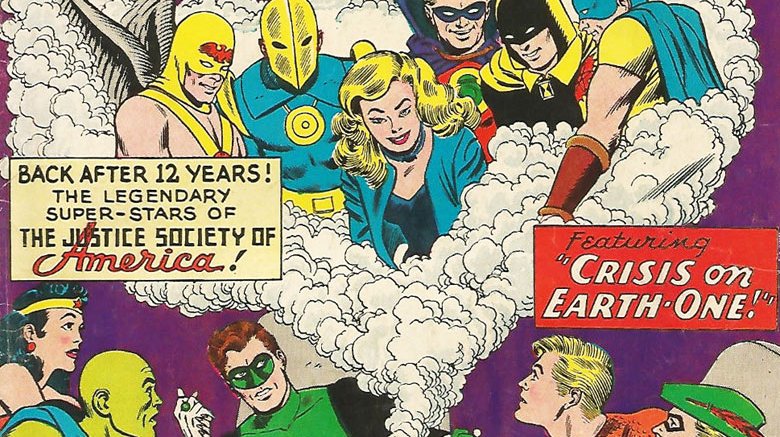

In 1961, Gardner Fox and Carmine Infantino had their all-new Silver Age Flash, Barry Allen, team up with his Golden Age counterpart, Jay Garrick. Looking back, it's a pretty weird story, especially the part where Jay only exists on Barry's Earth in the form of a comic book character, but it set the stage for what would happen the following year. In Justice League of America #21, Gardner Fox and Mike Sekowsky would expand the idea of a Golden Age character living on Earth-Two to revive the entire Justice Society for a cross-dimensional team-up.

This was, by any measure, a big deal. Not only was it an acknowledgement of a history to the DC multiverse, it presented the idea of a threat that even a team with the present day's most powerful heroes couldn't conquer without bringing in the heroes from another universe. It was successful, too, leading to a big multiversal team-up every year that would expand out to Earth-3, Earth-X, and, eventually, a Crisis on Infinite Earths. It was probably inevitable that Captain America would make a comeback, but I do wonder if Marvel would've been in such a hurry to bring back Golden Age characters like Cap and Namor if the JSA's return hadn't been a success.

Meanwhile, speaking of Marvel, Kirby, Stan Lee, Steve Ditko, and a handful of other creators were building the Marvel Universe around the idea that these were heroes who could always interact with each other. The flagship title was Fantastic Four, but the FF also appeared in the first issue of Amazing Spider-Man, and when they needed a lawyer, Daredevil would show up. In 1966, though, everything changed when a giant man in a big purple hat showed up and tried to eat the world.

"The Coming of Galactus" was the biggest story that Marvel had ever told, spread out over three issues with a world-threatening bad guy that even their most prominent heroes couldn't defeat on their own. But there was a crucial element to it: continuity. When the Silver Surfer was on his way to Earth, he didn't just fly through empty space, he passed by the Skrulls, a previous FF foe, so that they could talk about how this was an even bigger threat than they were. Galactus wasn't a threat to the FF on their own, he was a threat to the entire universe that characters like Spider-Man and Daredevil also shared.

This idea would come to its apotheosis at Marvel in 1984 with Secret Wars, the first Big Crossover Event that brought an entire universe together for one big story. Again, there are commercial concerns at play; it was named the way it was because a study by an action figure company showed kids liked the words "secret" and "war."

The shared universe

With the dawn of what Stan called the Marvel Age of Comics, the idea of a Shared Universe became one of the defining features, if not the defining feature, of superhero comics. It's a simple question of "if this, then this" — if Superman exists in this world, then there are people with super-powers and super-scientific technology, which means there's no reason that other characters who have those things can't also exist in that world. If Batman and Superman team up, then that means the Joker and the Riddler live in the same world as Lex Luthor and Brainiac, so why can't they team up too? If Spider-Man and Daredevil live in the same world, the same city even, as the Fantastic Four, then why doesn't Doctor Doom fight them?

Here's the weird part: while comics embraced that idea and answered all those questions and more, mass media studiously avoided it. Even though radio got there first, TV and movies studiously avoided shared universes. The closest you'd get would be sequels, spinoffs, or a continuation, like you see with Star Trek, but nothing spread out over multiple series and contained different genres in the way that comics did. Even within the same series, the focus was tighter. When superheroes moved to TV and movies, they followed suit, with a tighter focus that eliminated the idea of a universe around them.

It's worth mentioning that Batman '66 played a little bit with the idea of shared universes, and even featured a full on crossover with Green Hornet, which is mostly notable for a scene where Bruce Lee makes a pretty convincing attempt to kick Burt Ward's head off his neck and into the next county. Mostly, though, the idea was confined to cameos as Batman and Robin climbed up skyscrapers, and as much as I like the idea that the Addams Family, Hogan's Heroes, and a wealthy carpet manufacturer exist in the same universe, they never really pay that off.

Flirting with a universe

For years — decades, even — the only real mass media version of a superhero universe came from one of the most unlikely sources ever: a truly bizarre pair of live-action specials called Legends of the Superheroes from 1979. If you've never seen them, they're basically variety shows, complete with laugh tracks, full of DC Comics characters telling jokes and roasting each other while a villain makes a nominal amount of trouble. Adam West and Burt Ward come back as Batman and Robin, but the rest of the cast is made up of some truly deep cut characters. Solomon Grundy, Weather Wizard, the Huntress — Hawkman's in this thing. Hawkman's mom is in this thing!

But beyond that, everything had a much tighter focus, and again, it's not hard to see why. If you're making a movie about Superman, you don't need any other characters to add to the appeal. If you're making a TV show about the Incredible Hulk wandering around doing odd jobs, then having Iron Man show up might raise some questions that a TV budget is not equipped to answer.

This might come off as heresy, but it's one of the reasons that the DC Animated Universe, as good as it is, is built on a weird foundation that it doesn't really mesh with. Batman: The Animated Series presented its title character as utterly unique; even when someone like Zatanna showed up, it was in a very retro-pulp style. Like a lot of DC comics, it just wasn't originally meant to be a part of the universe it eventually expanded into.

The MCU and Infinity War

The MCU movies were different. From day one, literally the first movie in the franchise, there's an idea that we're building a universe. Nick Fury doesn't show up and ask Iron Man about making Mandroid armor for SHIELD, he talks about the Avengers, and the movies that follow focus on building individual characters to be a part of this universe before actually combining them into it.

That's what sets them apart from other film series. You'd never call Captain America: The First Avenger a sequel to Iron Man 2, but in a very real way, it is. They're all existing within the same universe and building to the next one even when they focus on individual characters, which makes them feel like a cohesive whole. And one of the reasons they work so well — and that stuff like Universal's hilariously botched attempt to create their Monster Mash universe doesn't — is that they're building on a structure that already exists. We've got at least 50 years of knowing how these characters are supposed to relate to each other, and seeing how these elements fit together in the big, complicated puzzle that is a shared superhero universe. They work because they have continuity.

As a friend of mine once said, "continuity" is just a fancy word for "stuff makes sense." It's that key element that makes a superhero universe work, that allows for characters to interact with each other while still retaining their core. It is, at heart, what people love about superhero universes, that simple flow from one thing to the next that gives them a logical consistency you can engage with. The Hulk exists in those movies because of attempts to recreate Captain America's super-soldier serum. Tony Stark creates Ultron because he's terrified of living in a world where the existence of superheroes is changing the rules in a way the smartest guy in the room can't understand. If you were wondering why the Shocker only has one gauntlet in Spider-Man: Homecoming, it's because they're actually the ones Crossbones had in Captain America: Civil War, and Cap only got one away from him before Crossbones blew up.

That's how we got to Infinity War and, to be fair, DC's shared universe CW shows, too. They embrace decades of comics built on the ideas that if one superhero can exist, then others can follow, and if multiple superheroes can join together for a team, then multiple teams can come together when there's a threat big enough. It's the logic and language to these characters that makes all of this possible. It happens because it has to.

If this, then this.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."