From Hell BTS Facts Only Johnny Depp (& Jack The Ripper) Would Know

In the dying years of the 19th century, the streets of Whitechapel in London were plagued by the murderous hand of history's most famous serial killer, Jack the Ripper. The monster in a cape and a top hat killed and mutilated at least five women before he disappeared back into the shadows, taking his true identity and motives for his macabre butchery with him. For (per Science), hard and fast proof regarding the man behind the notorious murders has constantly evaded Ripperologists. What we are left with is hearsay, speculation, and conspiracies — some outlandish, some plausible.

In 2001's "From Hell," filmmakers the Hughes Brothers explore one of the more flamboyant theories surrounding Jack the Ripper. Adapted from the graphic novel of the same name by writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell, the movie barely pauses for breath as it drags the viewer across the cobbles, through the fog, and into the gaslit streets where Jack carried out his deadly trade. In "From Hell" the royal family, freemasons, high-ranking police officers, and well-respected surgeons are all up to their knees in the blood of the Ripper's victims. It's thought-provoking stuff that captures the darker side of the Victorian era perfectly. Here are a few facts about the film, plucked from the mist and murk of time.

From Hell was filmed in Prague

Although covered in a cloak of anonymity, Jack the Ripper remains the world's most notorious serial killer. He is also as much a part of London's old East End as the Blitz, the Kray twins, jellied eels, and West Ham FC. So it's something of a surprise that a film about the monster of Whitechapel was filmed in Prague. According to set designer Martin Childs, the decision was made to film in the Czech capital because the London of Jack the Ripper had all but disappeared (via The Guardian). Yet there was a problem with Prague. Childs explained, "None of it looks like London when you began to examine it; it just looks old."

An alternative plan was hatched to build a complete Whitechapel set on a field located just outside of Prague in the small village of Orech. Borrowed cobblestones from the streets of Prague added a touch of old-world authenticity but the rest of the 9,000-square-yard set was built from scratch. In the official "From Hell" production notes, Childs explained, "We couldn't find anyplace here that resembled Whitechapel from all angles, so we ended up building it in the middle of a field. It became the unexpected highlight of the entire enterprise." He added that due to restoration work in Prague they "were able to borrow cobblestones from the city." Castle Hradek, Opocno Castle, Castle Minisek, Prague Castle, Castle Kacina, and Castle Doksany were also used to shoot scenes. Queen Victoria talking in Buckingham Palace, the Freemasons meeting, the Elephant Man cameo, and the mortuary examinations were all shot in these stately and historic locations.

The From Hell set was hailed for its authenticity

Although much of it has been gentrified and homogenized by market forces, London's old East End had a definite character. To some, it may have been an unsavory and hard-to-digest character, but the dimly lit and winding alleys, the raucous public inns, the music halls, the markets, the doss houses, the crumbling slums, and the scattered courtyards are part of the reason that Jack the Ripper has not been buried by history alongside others of his ilk. The setting where he carried out his dark deeds conspires to evoke something striking in the modern imagination. Getting the environment just right is essential for anyone planning a film on the Ripper, and the Whitechapel in "From Hell" has been acclaimed as an authentic recreation by those in the know at Casebook: Jack the Ripper.

Getting in on the action, The Guardian even suggested that the spectacular set designed by Martin Childs should have been preserved to give future generations a taste of 19th century London. Whitechapel landmarks such as the Ten Bells Saloon, Christ Church, and Commerce Street were painstakingly and lovingly recreated in a bid to capture the essence and atmosphere of this particular part of London. In the production notes for "From Hell," co-director Albert Hughes explained, "We wanted to definitely portray the environment of Whitechapel, and this set is as close as we could possibly achieve." Johnny Depp, who plays Inspector Abberline, added, "I was stupefied the first time I walked down these streets. It was incredible. The Hughes brothers are sticklers for details. Martin (Childs) did an unbelievable job"

The Hughes Brothers considered other actors before Johnny Depp

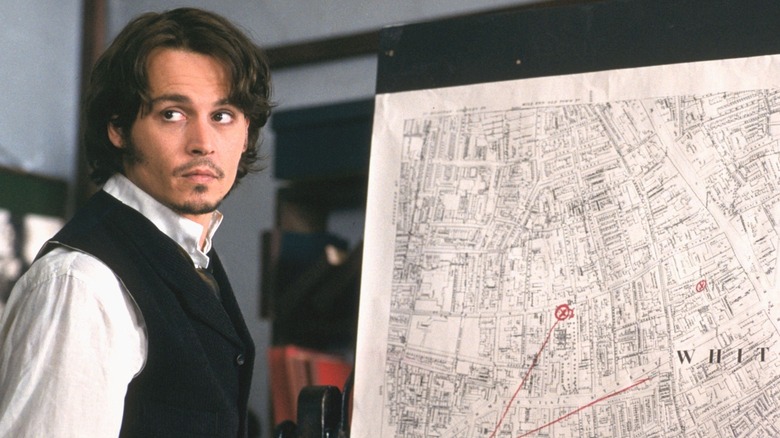

In most of his film roles, Johnny Depp brings something unique, engaging, and memorable to the table, even if it's an accent that ping-pongs back and forth between plausibility and hilarity. In "From Hell," Depp brings a melancholy and haunted air to the role of Inspector Abberline. He's no hard-bitten, cynical cop or even a man of action, but a soul who plods along trying to his best to do the right thing in a world gone wrong. Depp's restrained but engaging performance is integral to the film and his detached, civilized, and unruffled demeanor contrasts nicely with the savage glee and primal violence of Jack the Ripper.

Interestingly, Depp wasn't the Hughes Brothers' first choice for Inspector Abberline. The Guardian reports that Allen and Albert Hughes initially considered Daniel Day-Lewis for the role, and at one point Sean Connery was in the running. Discussions were also held with Brad Pitt and Jude Law before Depp came on board and made the role his own. The directors and Depp had previously discussed making a film on Howard Hughes together, but "From Hell" just felt right. Allen Hughes explained, "[Depp] was really into the material and he really wanted to do it. He has, like, 70 books on Jack the Ripper."

The real-life Inspector Abberline wasn't an opium addict or psychic

"From Hell" begins and ends with Inspector Abberline chasing the dragon in an opium den. In between, he has all sorts of disturbing and surreal visions regarding the Jack the Ripper murders. Yet in reality, Abberline was a no-nonsense and hard-boiled sort of cop and not the eccentric, drug-addicted dandy portrayed by Johnny Depp. According to Casebook: Jack the Ripper, when the Ripper murders began, Frederick Abberline was described in contemporary reports as being an overweight 45-year-old who looked like a banker. Sergeant Godly, played with thunderous bombast by the late Robbie Coltrane, was also Abberline's junior. In "From Hell" Depp's untroubled and unravaged appearance make it appear as if Godly is Abberline's senior.

Although Cinema.com reports that Johnny Depp is on record as saying, "Abberline has been beaten up by life. He lost his wife and child and relies on self-medication to get through the day," Abberline's drug use has no basis in reality. Rather, it may simply be a tool employed by the filmmakers to help explain the psychic visions that plague him in "From Hell." In Ripper lore and the graphic novel, there is a character named Robert James Lees, who believes he has psychic powers and contacts Scotland Yard to offer his services. The Inspector Abberline in "From Hell' appears to have incorporated aspects of both figures. As "From Hell" executive producer Amy Robinson explained, "Abberline is a character reminiscent of the protagonists of classic 19th century novels. He is a flawed hero enduring an enormous internal struggle while trying to cope with horrendous unfolding events."

Johnny Depp has a lifelong interest in Jack the Ripper

The case of Jack the Ripper has exerted a dark fascination and morbid curiosity over many who have stumbled across this bloodstained chapter in history. It remains a nightmare forever hovering on the edge of consciousness and a mystery that will never be solved. However, that does not stop hordes of would-be sleuths pulling on their Sherlock Holmes deerstalker and monocle and going on the hunt with every passing year. The study of the unidentified killer even has a word: Ripperology, and its students are referred to as Ripperologists. Now, while Johnny Depp may not be a fully committed and dues-paying member of the Ripperologist club, he maintains that he has held a lifelong interest in the murderer of Whitechapel.

IGN reports that during a roundtable interview in Los Angeles to promote "From Hell," Depp revealed his interest in Jack the Ripper developed as a little kid. "I can remember stumbling upon a documentary about the Ripper case when I was around seven or eight that sort of sparked my interest," he recalled. "Grisly murders left unsolved, and there are so many possibilities and theories ... it's all just fascinating." His co-star Heather Graham, who plays Mary Kelly in the film, elaborated that during their research for the film they met a Ripperologist who hit it off with Depp. Revealing that he has nothing but admiration for Ripperologists, Depp explained, "It's amazing the details these guys know. And I've read a lot of the materials, so I can hold a fairly steady conversation with them. But it's really a life's work for these guys."

Alan Moore wasn't a fan of the movie adaptation of his graphic novel

Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell's "From Hell" often tops the must-read lists of graphic novels, because it's all muscle and no fat and shows what comic books are capable of. Unfortunately, in common with many of Moore's other great works which have been adapted to the big screen such as "Watchmen" and "V for Vendetta," the writer was not exactly a fan of "From Hell." In an interview with Ian Winterton, he explained that because he and Eddie Campbell owned the rights to "From Hell" he was happy for it to be turned into a film and take the cash, but insisted from the get-go that the movie and the graphic novel would remain two distinct entities. He also revealed he had no real interest in watching the Hughes Brothers' adaptation.

Moore explained he didn't wish to insult or offend anyone involved with the movie, but insisted that movies as a whole weren't his cup of tea. Moore later attempted to watch "From Hell" and revealed, "I think I got ten minutes into it and realized that it had been a bad idea to watch after all. I thought the trailer was enough but I thought I should at least try to be fair. I just thought it was a travesty, so I turned it off." Style issues aside, the biggest difference between the book and the movie is the former reveals the identity of the killer ten pages in and the movie is a whodunnit that keeps the viewers guessing until near the end. Each has its merits and each medium plays to its strengths — variety, after all, is the spice of life.

The conspiracy theory From Hell is based upon has been discredited by most Ripperologists

The conspiracy theory that is the meat and bones of "From Hell" was influenced by Stephen Knight's book, "Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution" (via Casebook: Jack the Ripper). Within its pages, Knight makes the case for a conspiracy that involves Prince Albert, Freemasons, the artist Walter Sickert, and the Queen's surgeon William Gull. It's heady and intoxicating stuff that hints at cover-ups at the highest levels and a level of institutionalized corruption that beggars belief. Unfortunately, on closer examination (and if Ripperologists specialize in one thing, it's scrutiny), the dots don't connect and the facts don't add up. Casebook reports that the tale told firsthand to Knight by Walter Sickert's son Joseph involved Prince Albert recruiting his father's help to mix with the commoners in Whitechapel. One of these dalliances saw him getting shop girl Annie Elizabeth Crook pregnant. When his grandmother Queen Victoria found out, she was furious and unleashed hell in an attempt to cover up the royal indiscretion,

Before Crook was taken away for Gull to experiment on in the hospital, she had told her friend Mary Kelly of her affair with the Prince. Kelly in turn told her friends and they hatched a plan to blackmail the royal family. Big mistake. Gull was told to sharpen his knives and await the call. The rest is history. The theory falls somewhat short considering that Sickert later admitted he made the whole thing up not long after the book's publication. Additionally, there's a nagging lack of evidence to substantiate any of it. Nevertheless, it remains a splendid yarn and the stuff films are made of.

Trevor Jones was influenced by Freemasonry when composing the score for From Hell

Any film about Jack the Ripper requires a musical score that is tense, fraught, suspenseful, haunting, unnerving, and possesses a strange and savage beauty. In a bid to tick all those boxes and more, composer Trevor Jones employed the services of Bill Brooks. The bass-baritone was on board to lend a little Mongolian chanting to the score to try and capture the elements of conspiracy and freemasonry inherent in "From Hell." In an interview with Soundtrack.net, Jones explained that Brooks "did this Tuvan chant — it's a kind of Mongolian Buddhist chanting. It lent a wonderful aspect to the score."

Jones went on to explain exactly why he introduced the chanting. "I was looking for a mystical element. The whole of the Freemasonry thing is bound up with mystic symbols and rituals and I wanted to bring out that aspect of the organization."

He also revealed that he believed Jack the Ripper wasn't some murderous lunatic acting alone but an individual who had links to the British establishment and its tangled web of privilege, class, and conspiracy. Jones believes freemasonry to be an embodiment of that. The composer continued, "This is something that was almost part of the British establishment that had this bizarre thing steeped in mysticism — that part of the culture of this country that these people who belonged to the various castes and so on had this mystical aspect to them that resulted in virtually wiping out half a dozen women. It's unbelievable, really!"

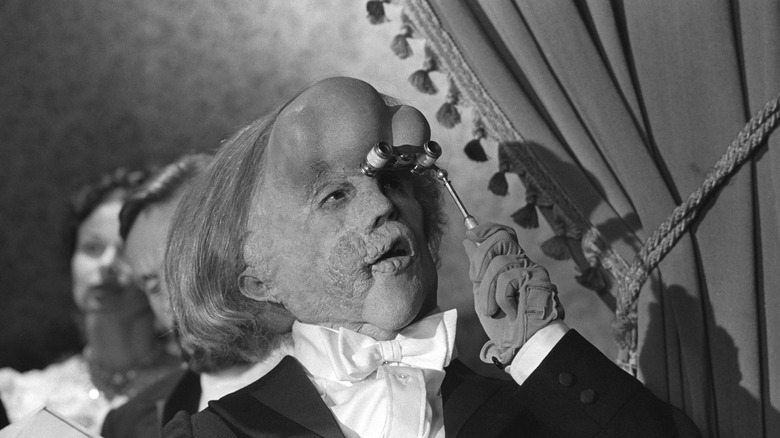

From Hell marks the first time movie audiences saw the Elephant Man in color

When David Lynch's "The Elephant Man" hit screens in 1980, the abuse, prejudice, and hardship Joespeh Merrick was forced to endure during his life touched a nerve with audiences everywhere. Played with pathos and sensitivity by John Hurt, the actor was completely unrecognizable under the layers of prosthetics make-up artist Christopher Tucker had used to capture Merrick's unique features. Dangerous Minds reports that Hurt would sit in the make-up chair for at least seven hours as Tucker slowly transformed him into Merrick. The results spoke for themselves and had a huge effect on the film's impact. But because "The Elephant Man" was shot in black and white, it wasn't until the release of "From Hell" in 2001 that Merrick's brief cameo allowed audiences to see his likeness in color for the first time.

According to Albert Hughes, Merrick's appearance in "From Hell" was used because of "the weird connection with him during that time period" (via Cinema.com's "From Hell" Production Notes). The co-director explained, "Merrick lived in a flat that was within walking distance of the murders. He was actually cared for in a hospital down the street." Millennium Effects spent months researching Merrick's body casts and six hours applying the final prosthetics. Steve Painter explained, "This is the first time audiences will see the Elephant Man in color and such graphic detail. He is beautifully tied in with the story, which enriches its sense of history."

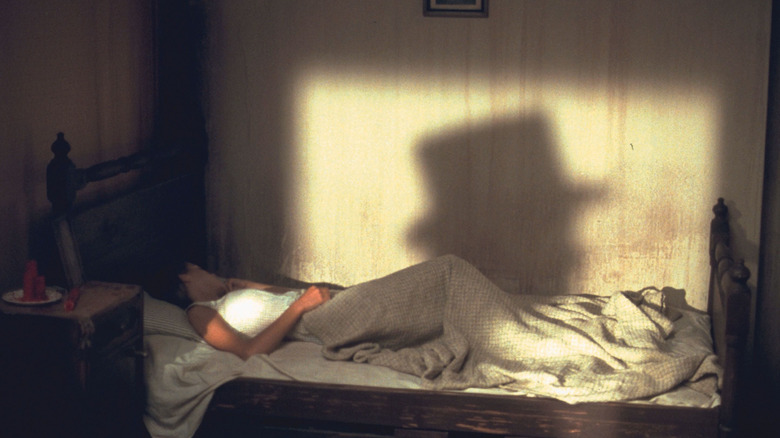

There is no evidence the Ripper's victims knew one another

Both the graphic novel and film adaptation of "From Hell" rely on the five canonical victims of Jack the Ripper knowing one another. For the royal conspiracy theory to work, Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly must have all been reasonably well acquainted. In reality, there is no evidence that any of the unfortunate ladies were anything but strangers to one another in life, before they were united in the worst possible way in death. In her groundbreaking book, "The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper," author Hallie Rubenhold makes the convincing case that not only did the canonical five not know one another, but there is no evidence to suggest that three of them were even sex workers (via The Sun).

Rubenhold writes, "The victims of Jack the Ripper and their lives have become entangled in a web of assumptions, rumor, and unfounded speculation." She adds that the narrative which defines their history is "male, authoritarian, and middle class," pointing out that the coroner's inquests found no evidence of sexual assault by the Ripper. She also draws the intriguing conclusion that because there had been no evidence of a struggle in the murders and that three of the ladies had been killed in reclining positions, the Ripper must have targeted his victims whilst they slept. She believes the police were so blinded by the cast-iron belief that the Ripper only murdered sex workers that they were missing his true modus operandi.

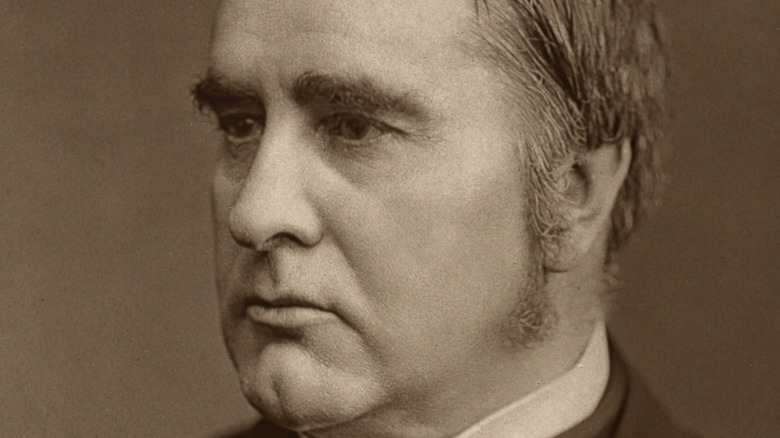

The real-life William Gull was an acclaimed physician

The surgeon William Gull gets something of a raw deal in "From Hell." Played with a fine mix of civilized menace and psychopathic rage by Ian Holm, the film is seemingly hell-bent on casting Gull's reputation in stone as a depraved monster who delights in torture and butchery. Gull is far from the only historic figure who has had his reputation mangled by the perpetually grinding wheels of the Jack the Ripper industry. History Collection reports that at some point, Lewis Carroll, Prince Albert, Walter Sickert, and forgotten songwriter Michael Maybrick all stalked Whitechapel delivering death and despair. Yet although it is conceivable one of them might have been the Ripper, it is just as conceivable to suggest they're all innocent.

William Gull spent his career developing treatments for diseases and disorders. He coined the term "anorexia nervosa" and was famed for his skills in diagnosis. He was also an early supporter of the then-radical campaign to ensure women were able to pursue a career in medicine. Even Eddie Campbell, the artist responsible for the "From Hell" graphic novel, believed Gull was given a bad rap. "He (Gull) was probably a great man. He's not just this obscure figure he did things that are still relevant to the present age," Campbell told Entertainment Weekly. "He was the first person to understand anorexia and give it a name, and we've made him into a madman. I prefer to think we've made a madman who just happens to have the same name as him. I think we've created a villain on the scale of Hannibal Lecter."

The title allegedly comes from Jack the Ripper himself

The expression "From Hell" is not one you're likely to forget in a hurry. It has punch, power, and a certain poignancy. Anything described as being from a place where all manner of infinite torment and suffering is carried out daily is going to leave a vivid impression. On October 15, 1888, the Chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, George Lusk, received a letter purportedly written by Jack the Ripper in red ink and signed "From Hell." The horror was compounded by the fact it was sent alongside a kidney the letter writer claimed to have belonged to Catherine Eddowes (via All That's Interesting). Eddowes had been murdered two weeks previously, and it was common knowledge she had been disemboweled and her kidney removed. There was also a distinct lack of scientific means to test if the kidney belonged to Eddowes.

Nevertheless, amongst the pile of letters sent to the police, the "From Hell" missive is thought to be authentic. The notorious and (perhaps deliberately) badly-spelled correspondence, reads, "From Hell. Mr. Lusk. Sor I send you half the kidne I took from one women preserved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nose. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer. Singed Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk." The letter vanished from the police archives not long after it was photographed and filed, but the title remains — scarred into the world's collective consciousness.