Everything Cinderella Man Doesn't Tell You About The True Story

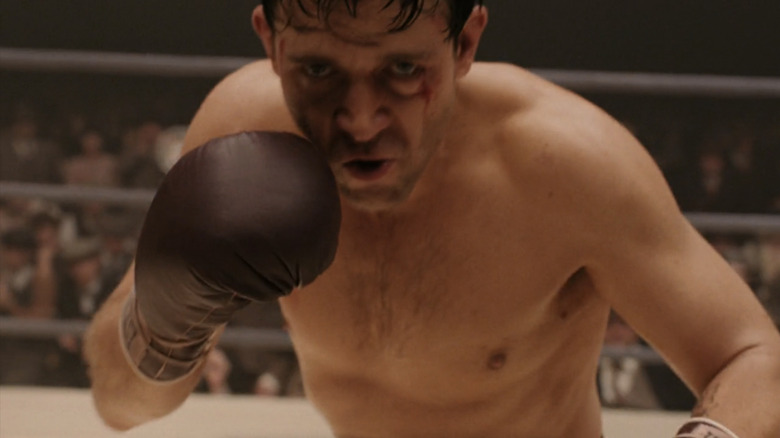

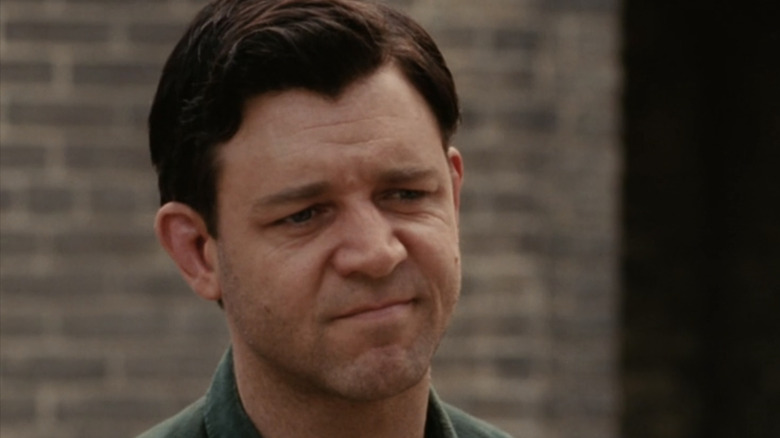

Ron Howard's 2005 crowd-pleaser "Cinderella Man" tells the true story of James J. Braddock (Russell Crowe), an up-and-coming boxer in the 1920s whose career hits a series of setbacks; by the mid-1930s he is taking shifts as a dockworker in New York City in order to provide for his wife Mae (Renée Zellweger) and their three children. But with the support of Mae and his longtime manager Joe Gould (Paul Giamatti), Braddock makes an improbable comeback in the ring and gets a shot at the heavyweight title, currently held by the fearsome Max Baer (Craig Bierko).

It's an old-fashioned sports flick, not terribly different from the kind of boxing melodramas that were popular when Braddock's comeback was making headlines. Apart from some fictionalized characters like Paddy Considine's stockbroker-turned-longshoreman, the film presents an improbable comeback more-or-less as it actually happened.

Braddock's triumph in the ring was celebrated, then as now, as a tribute to the working class spirit of America, struggling mightily against the Great Depression. But real life is always stranger, or at least more expansive, than fiction, even for a film as well-done as "Cinderella Man." Here are some details about the life and times of James Braddock that didn't make it into the finished film.

Plain Jim

Writer Damon Runyon, whose vivid chronicles of Depression-era New York City inspired the musical "Guys and Dolls," was particularly enamored of Braddock, and his coverage of the Baer fight in June 1935 for the New York American (via Deadline Artists) not only coined the nickname "Cinderella Man" but established the All-American symbolism that forms the backbone of Howard's film. Runyon first told the story of how Braddock's fortune (both in terms of money and luck) vanished in the 1929 stock market crash, how he was forced to go on the dole ($24 a month from the state of New Jersey) to support his family, and how he used his winnings from his 1934 upset over John "Corn" Griffin to pay back the state welfare office; Runyon at least qualifies that last improbable detail with a "so it is said."

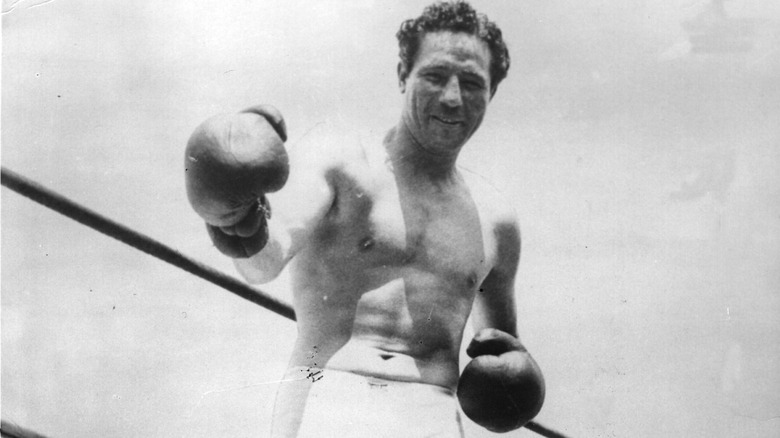

But Braddock had a number of nicknames over the years, and the one that perhaps suited him best was "Plain Jim," coined by newspaperman and early sportscaster John Kieran, according to Braddock's 1968 New York Times obituary. He was by all accounts a humble man out of the ring, soft-spoken in the best of circumstances (Runyon's column called him "inarticulate"), but even more so when compared to the boisterous and colorful Max Baer. Braddock let his fists and his indomitable spirit speak for him, as well as his blustery manager Joe Gould.

Long rounds, short years

Most boxers have very short professional lives, then as now. A very lucky, elite few have been able to last two decades or more at the top of their field: Muhammad Ali, Bernard Hopkins, Manny Pacquiao, Floyd Mayweather. For the vast majority, their time in the ring burns bright and fast, capturing the highs and lows of an entire career in just a handful of short years, and all but the luckiest of them wind up wearing those years on their faces and bodies — cauliflower ears, broken noses and fractured eye sockets, if not far graver injuries.

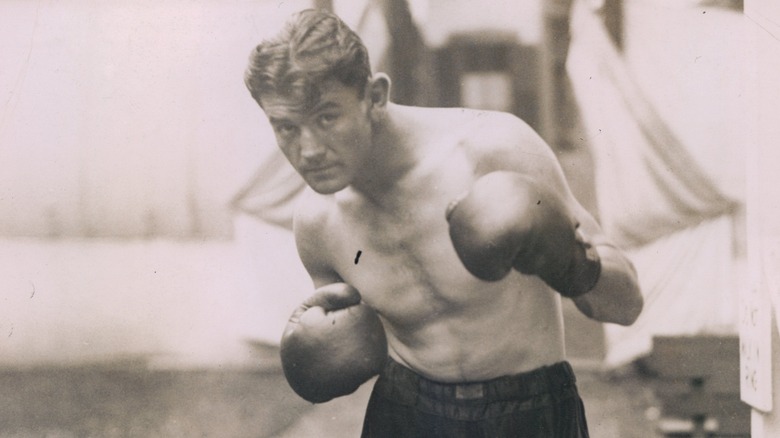

Braddock's face bore the marks of not just his struggles inside the ring, but outside, working as a longshoreman in between fights to support his family, bearing the worst years of the Great Depression on his shoulders like many of the men and women of his generation. When he faced Max Baer in 1935, having already washed out of boxing once only to stage an unbelievable comeback, he was only 29 years old; Baer was 26. To see pictures of them, you wouldn't be out of line to guess that they were older than that by at least a decade — especially considering how they were cast in the film. Crowe was 40 years old when the film was released, as was Bierko, making him a full 14 years older than the character he played.

From prospect to bum

The popular version of Braddock's life story, the one favored by Runyon and the 2005 film, pinpoints the start of his run of bad luck as his July 1929 loss to light heavyweight champ Tommy Loughran. Braddock went the distance with Loughran and remained standing at the end of fifteen rounds, but lost by unanimous decision. Coming just a few months before the 1929 stock market crash that began the Great Depression, the Loughran fight makes for a convenient turning point; Braddock fell on hard times just as the entire nation did the same.

But the truth is a little more nuanced. While the "Cinderella Man" myth would have you believe Braddock went from losing to Loughran at Yankee Stadium to working the docks the next day, he remained an active fighter through the early years of the Depression, fighting three more times in 1929 alone after facing Loughran. But while he had lost a few times in his career prior to Loughran, it's true that particular loss dimmed his star. Braddock would win only 11 fights out of more than 30 over the next three years, and was disqualified in his 1933 bout against veteran fighter Al Ettore in Philadelphia, apparently due to a lack of effort. A hand injury later in 1933 during a match against Abe Feldman kept Braddock out of the ring for nine months, the longest hiatus in his career up to that point, and the moment when the films finds him working the docks and drawing welfare, down but not out.

Hat in Hand

One of the film's most poignant moments happens in this period, when Braddock is injured and cannot make enough money to support his family. He's fallen behind on his milk and heat bills, and so he goes to the social club at Madison Square Garden, where Joe Gould and big shot promoter Jimmy Johnston (Bruce McGill) dine and drink with the other rich managers and promoters whom Braddock once rubbed shoulders with. Hat in hand, he asks them for help, only to be rebuffed by Johnston and the other fat cats who can't bear to look at him. Only Joe, tears in his eyes, stands to help his friend.

It's a wonderful moment for both Crowe and Giamatti (who earned the film's sole Oscar nomination for acting) and a turning point in their relationship. But did it actually happen?

Jeremy Schaap's 2005 book "Cinderella Man" (which was not used as source material for the film) tells a story of Braddock coming to Gould privately for money and Gould — often on the verge of financial ruin himself — giving him $35 dollars secretly on loan from Jimmy Johnston. While asking his former (and future) manager for a handout was no doubt a humbling experience for the proud Braddock, it was nothing like the public humiliation of the Hollywood version.

Joe Gould

Gould was in many ways Braddock's polar opposite. One was tall and Irish Catholic, the other short and Jewish. One was humble and self-effacing in public, the other was a showboat who threw money around, even (or especially) when there was little cash to go around. One was a monster in the ring but a soft touch outside; the other found that, after a fledgling attempt at bantamweight as a teen, he was much better at fighting on contracts than on canvas. The two had known each other since Braddock was a 20-year-old novice, and their personal friendship was just as important as their professional relationship; until Braddock won the championship, he and Gould's business agreements were all settled via handshake.

Gould died in 1950 after a short battle with leukemia, and while his partnership with Braddock would be his most lasting legacy, there was also a darker chapter in the later years of his life. Once the United States entered World War II, he and Braddock both joined the war effort and were assigned to the New York port of embarkation, thanks to Braddock's knowledge of shipping and dockwork. However, in 1944 Gould was dishonorably discharged and sentenced to three years of hard labor for accepting bribes in exchange for awarding Army contracts; it is unclear whether Gould served the entirety of his prison term.

Max Baer

In a 2005 interview with Entertainment Weekly, Jeremy Schapp — whose book on Braddock, also titled "Cinderella Man," came out just months before Howard's film — expressed concern that the film, which he had not yet seen, would demonize Max Baer in its effort to exalt Braddock.

His instinct was correct; the film's depiction of Baer as a high-rolling loudmouth who takes an Ivan Drago-like pride in having killed a man in the ring is arguably its biggest departure from the real life story. In 1930, Baer faced fighter Frankie Campbell in San Francisco; in the fifth round a blow to the head from Baer's right hand put Campbell on the canvas, ending the fight. Campbell would die from his injuries a day later.

Though Baer was very much a boastful man in real life and cultivated a "bad boy" image, Campbell's death was not something he was proud of; the night would haunt Baer for the rest of his life and nearly ended his career. After a grand jury found him not at fault, he continued to fight and used his winnings to financially support Campbell's widow. Proudly Jewish, Baer wore a Star of David on his trunks, and in 1933 defeated German boxer Max Schmeling; like Jesse Owens' triumph at the Summer Olympics in Berlin three years later, Baer's win was celebrated as a symbolic victory in the fight against fascism.

The Jinx Bowl

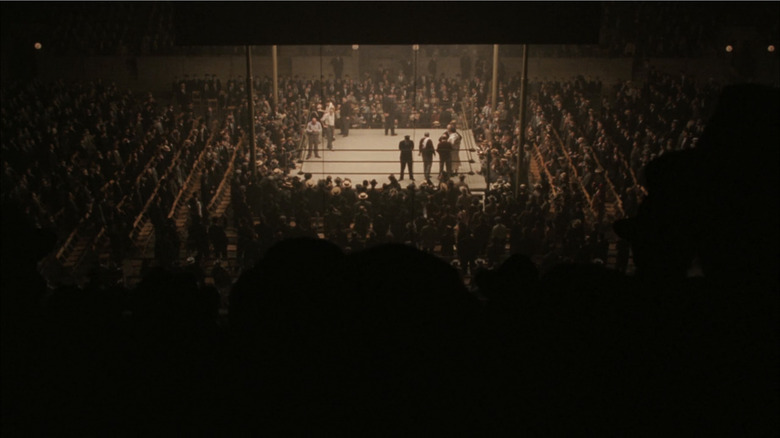

Both Braddock and Baer fought many times at Madison Square Garden, which sat then and now in the heart of midtown Manhattan. But for their one and only match together, the two men occupied a different venue: The Madison Square Garden Bowl, a 72,000-seat outdoor arena located in the Long Island City area of Queens. Though Braddock's defeat of Baer was an incredible upset, perhaps it shouldn't have been, as the Bowl had earned a reputation as a place where champions lost their titles, and an accompanying nickname: The Jinx Bowl. Runyon even commented on this strange phenomenon in his New York American article on the fight, naming it as "a place where no champion yet has defended his title."

Perhaps it had something to do with the fact that the Bowl's mastermind, boxing promoter Tex Rickard, died shortly before construction began in 1929, or that its first fight in 1932 was an upset, with Jack Sharkey winning the heavyweight crown from Max Schmeling. Perhaps there was just something off about the location's vibes that made fights there especially unpredictable. In any case, the Bowl's time as a boxing mecca in New York City was short-lived; it hosted its final match in 1938 and was torn down soon after. The land where it sat would host a mail-sorting facility during World War II, followed by a succession of factories and shopping centers over the next eight decades.

Joe Jeannette

Howard's film plays the climactic Baer-Braddock fight for maximum drama, switching between multiple points of view: Braddock, struggling in the ring against Baer's deadly blows; Mae at home in their tenement apartment, listening on the radio as the announcer breathlessly narrates each moment; and Joe Gould and trainer Joe Jeannette (Ron Canada) anxiously watching from the corner. Jeannette's presence in the scene is interesting; according to Schaap's biography, Braddock trained at Jeannette's New Jersey gym in the mid-1920s before switching to the more well-known Stillman's Gym in midtown. There's no mention in the book or in Runyon's contemporary report that Jeannette was in Braddock's corner, nor can he be seen in the filmreel footage of the fight.

Jeannette's inclusion here may not be accurate to history, but it does shine a light on the very real racial barriers that were in place for African American boxers in the early decades of the 20th century. Jeannette had been a heavyweight fighter in the generation before Braddock, in the era when Black fighters were barred, officially or unofficially, from competing against whites. Even after his contemporary Jack Johnson officially broke the color barrier by defeating Tommy Burns for the heavyweight title in 1908, Johnson refused to fight Jeannette or any other Black challengers, effectively reinforcing boxing's segregationist policy for another generation. Jeannette retired from the ring in 1919 and worked as a referee and trainer, and eventually converted his boxing gym into a limousine rental service. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1997.

Braddock vs. Louis

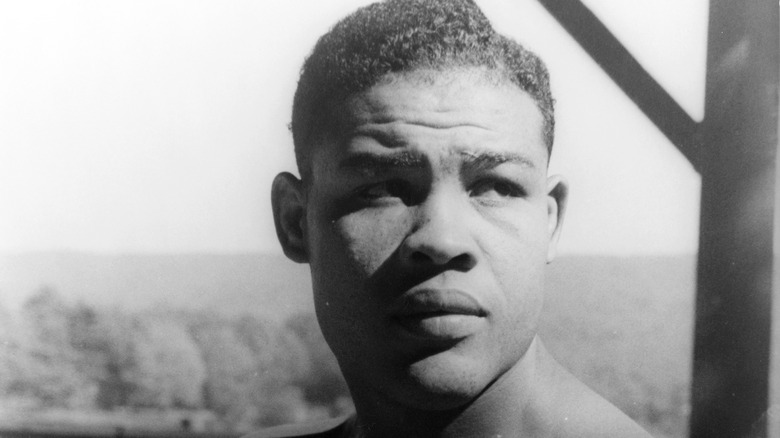

Considering his connection to Joe Jeannette, one of the great heavyweights of his era who never got a shot at the title, it's fitting in a way that Braddock lost the championship to Joe Louis, one of the greatest boxers of all time and only the second African American heavyweight champion ever.

Braddock's first and only title defense came a full two years after he defeated Baer; he and Louis met on June 22, 1937 at Comiskey Park in Chicago, home of the White Sox. The fight almost didn't happen, according to Schaap's biography (via the New York Post), as the Illinois Athletic Commission objected to it on racial grounds; the two men had to file a court appeal in order to force the commission's hand and allow the fight to proceed. After a first round knockdown by Braddock, Louis rallied and delivered a brutal knockout in the eighth round. For the first time in nearly three decades, a Black man held the greatest title in sports.

If that is all Louis had ever accomplished, it would have been enough to secure his place in the history books. But the Brown Bomber held onto that title for 12 years and over two dozen title defenses, the most of any fighter on record. Because of Louis — and, in a way, because of Braddock — there would never be another era when Black fighters were excluded from championship consideration. "[Braddock] broke the color barrier," said notorious promoter Don King, who served as a consultant for Howard's film. "That's what gave us the Brown Bomber."

Retirement and beyond

Joe Louis' eighth round stoppage ended Braddock's reign at the top of the heavyweight division, but it didn't end his career. Six months after losing to Louis, he faced British fighter Tommy Farr at Madison Square Garden. The fight was close, perhaps too close for Braddock's liking; despite winning by split decision, he announced his retirement less than two weeks later on January 31, 1938.

"I have spent 15 years in the game," Braddock said in a statement at the time, "and in fairness to everyone, but especially to my wife and children, I believe it is time for me to withdraw."

Braddock served in the Pacific theater in World War II as a captain in the Transportation Corps, where his experience on the docks of New York and New Jersey proved useful; he apparently was uninvolved in the bribery scheme that got his former manager Gould arrested and discharged. After the war, Braddock kept a low profile, working in construction and marine equipment and helping to construct the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in the early 1960s.

He died in November 1974, still warmly remembered for his incredible comeback story, immortalized by writers like Runyon and the fight fans who were there to witness it. Though his reign at the top was ultimately short-lived, he nevertheless earned his place amongst the lineal champions of the sport, a roster of pugilistic succession that stretches more than 130 years, from John L. Sullivan in 1885 to Tyson Fury today.