The Ending Of Rocky Explained

The Best Picture race at the 1977 Academy Awards was a tight one, with five all-time classics vying for the top prize: Martin Scorsese's immortal portrait of urban decay "Taxi Driver," Hal Ashby's pastoral Woody Guthrie biopic "Bound for Glory," Sidney Lumet and Paddy Chayefsky's television satire "Network," Alan J. Pakula's Watergate docudrama "All the President's Men," and "Rocky," John G. Avilden's boxing drama that had a great underdog story both on-camera and behind the scenes. Star Sylvester Stallone was plugging away in bit parts when he wrote the screenplay — about a washed-up Philadelphia club fighter who gets a shot at the heavyweight championship — as a vehicle for himself. When Hollywood came calling, they wanted pretty much anyone else but Stallone in the title role, but he stuck to his guns (via Insider), and the result was not just the biggest hit of 1976 (per The Numbers), but one of the most successful film franchises of all time.

"Rocky" won the big prize that night, as well as best director for Avildsen (via Oscars.org). In hindsight, the film's critical and commercial success is often seen as the death of the pessimistic adult dramas of "the New Hollywood" in favor of big franchisable crowd-pleasers like "Jaws" the year before and "Star Wars" the year after. But "Rocky" has more in common with its fellow nominees than you might remember, a throwback to the working class melodramas of an earlier generation with little of the cartoonish, Cold War-winning fantasy that would come to mark the series, and an ending that finds victory in defeat.

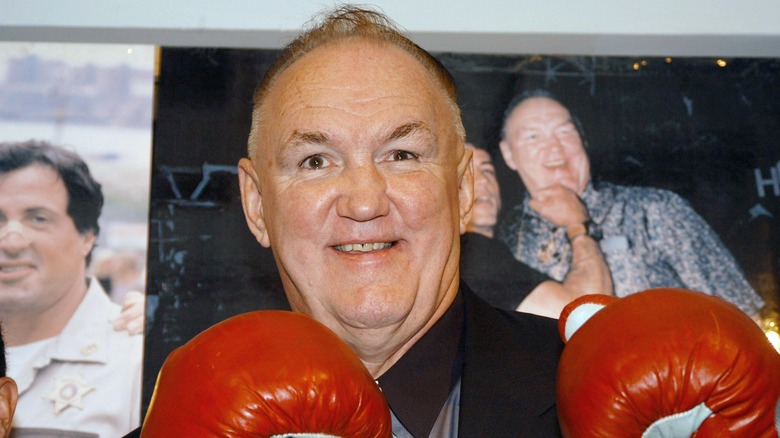

Ali vs. Wepner

"Rocky" is very much a work of fiction, a parable about second chances in life, but Stallone's inspiration came from a real-life event: the 1975 fight between heavyweight champ Muhammad Ali, who had just defended his title against George Foreman in the legendary "Rumble in the Jungle" match, and New Jersey boxer Chuck Wepner, nicknamed "the Bayonne Bleeder" for how often he was injured in the ring (via The Sportsman). Ali was an Olympian, a decorated champion, and one of the most famous men in history. Wepner, on the other hand, had never been a full-time boxer; he scheduled his training around his day job as a liquor salesman (via TIME). Despite Ali being a 10-1 favorite, Wepner held on for a punishing 15 rounds, getting in a lucky shot and dropping Ali in Round 9 before losing to the champ by stoppage in the final seconds of the fight.

Wepner and Stallone have had a contentious relationship over the years; Wepner was never officially credited or compensated for his life story, but has spent decades making appearances as the "real" Rocky, resulting in a 2003 lawsuit that was settled out of court (via the New Haven Register). He spent his post-Ali glory years fighting intermittently, including a 1976 novelty match with wrestler Andre the Giant that closely resembles a scene in "Rocky III," before serving prison time on drug-related charges. He has been the subject of two recent biopics, 2016's "Chuck" starring Liev Schreiber and Naomi Watts as Wepner's third wife Linda, and 2018's "The Brawler" starring Zach McGowan.

It doesn't really matter, does it

Other than the general premise of the film and the fighters' East Coast backgrounds, there actually isn't much alike between Wepner's life and "Rocky," and even the particulars of the climactic match between Rocky and Ali stand-in Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers) are not terribly similar. Wepner's fight with Ali was meant to be a small affair, a tune-up after his rope-a-dope war with Foreman, while Creed-Balboa is presented as the biggest fight of the year. But despite the differences, one thing between them is especially true: Neither man was there to win. Despite the claim that the fight is a celebration of America as a land of opportunity, giving an unknown fighter a shot at the biggest title in sports, no one thought that Rocky ever stood a chance.

The film illustrates this in a quiet scene just before the fight, as Rocky walks through the empty stadium and stares up at a giant banner hanging from the rafters with his likeness painted on it. On the other side of the ring, a banner with Apollo. He sees Apollo's manager Miles Jergens (Thayer David) and notes that the banner has the wrong colors on his trunks — white on red instead of red on white. Jergens smiles and takes the cigar from his mouth. "It doesn't really matter, does it?" he says, "I'm sure you're gonna give us a great show." It's a reminder of how little he is respected, and how his being there is considered a gimmick by just about everyone.

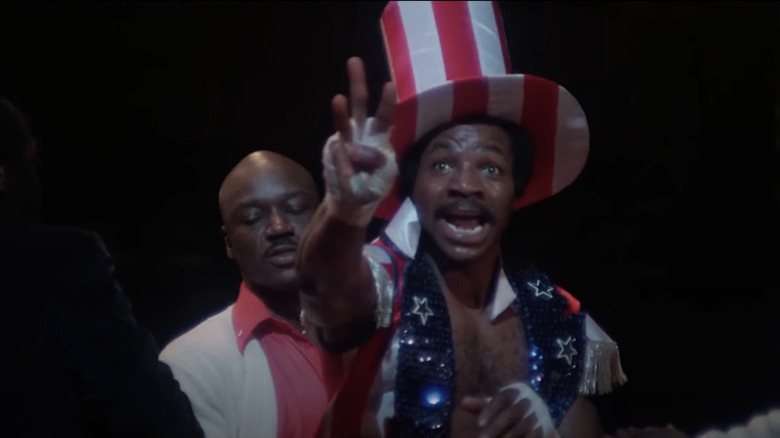

He looks like a big flag

Of course, Rocky is a gimmick, at least before the first bell rings. There is no world where this unknown fighter — so unknown, in fact, that he is chosen out of a printed directory of active Philadelphia boxers — would get such a shot at the heavyweight crown. The fight is a massive publicity stunt meant to bolster the reputation of Apollo, who enters the stadium on a parade float designed to look like Emanuel Leutze's famous painting, "Washington Crossing the Delaware," handing out coins to the crowd and flanked by women in silver body paint dressed as the Statue of Liberty. When he arrives in the ring, he doffs his Continental Army-like cloak and white wigs to reveal a pair of star-spangled trunks and waistcoat. Rocky looks on, dumbfounded. "He looks like a big flag," he says to his trainer Mickey (Burgess Meredith).

Of course, Apollo isn't just being patriotic, but playing on a year's worth of Bicentennial excitement. Celebrations for the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence carried on throughout 1975 and '76, with parades and special events, commemorative items, and even a Revolutionary War theme park, Libertyland, which opened in Memphis in 1976 (via Memphis Flyer). Apollo picks Philadelphia, home of Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, and a white Italian opponent specifically to stoke patriotic sentiment. The fact that "Rocky" also came out in 1976 makes it both a satire of Bicentennial fervor and a sincere example of the same.

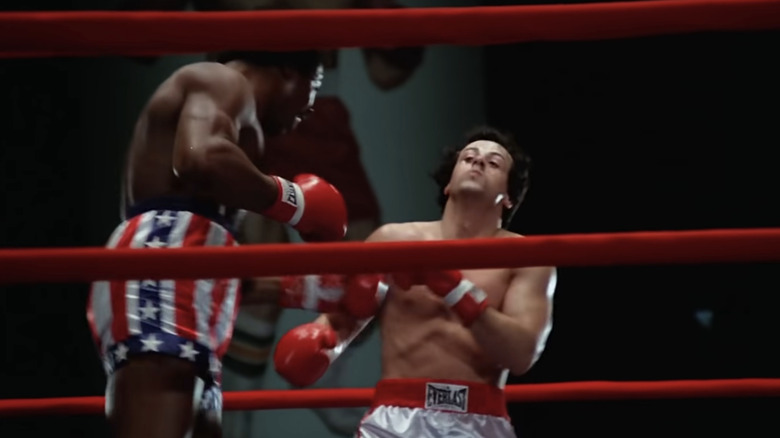

Big swings

Boxing is a subtle sport. Most fights are won on the scorecard through patience, determination, and strategy, and knockout victories are often so fast and so smooth that they often don't even register to an audience until a fighter is on the canvas. Take the so-called "phantom punch" that ended the rematch between Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston, for example, or the way that Canelo Alvarez's stoppages are not lightning bolts from the sky but rather the steady accumulation of punishment to his opponent's body. Boxing films, on the other hand, are very much unsubtle; the drama in the ring should be an expression of the drama out of the ring and vice versa.

The language of boxing in "Rocky," the big brutal hits that a later sequel would describe as "hurtin' bombs," was written by fight choreographer Jimmy Gambina (via Total Rocky). A part-time actor in the 1960s and early '70s, Gambina was initially hired by the production to train Stallone, but his work there eventually led to him choreographing Stallone and Weathers in the film's climactic match. For his efforts, he received a shout-out from director John G. Avildsen during his acceptance speech for best director at the Academy Awards the next year. In the years since, Gambina's worked as a stunt trainer and choreographer on "Saturday Night Fever," the Brian De Palma thriller "Snake Eyes," and many other boxing films (via IMDb). In 1990, he returned to the world of Philadelphia with a small acting role in "Rocky V."

Cut me, Mick

Despite Gambina's technical expertise, certain elements had to be bigger than life. One of the most famous (and parodied) moments in "Rocky" occurs in the final fight as Rocky, his right eye nearly swollen shut by Apollo's thunderous swings, tells Mickey to cut his eyebrow in order to relieve the pressure over his eye and allow him to keep fighting for the final round. "Cut me, Mick," he demands; Mickey looks around discreetly while his cutman (Al Silvani) makes a quick incision over Rocky's eye. Bright red blood spurts out from the wound, but Rocky is able to see again and carry on.

In real life, of course, the job of the boxing "cutman" is to repair cuts, not create more of them (via World Boxing Association). The tools of their trade include ice packs and cold compresses to reduce swelling, with petroleum jelly and adrenaline solutions to temporarily staunch any bleeding wounds. The inherent risk in a move like actually slicing open a fighter's swollen face to relieve the pressure is that the cutman might not be able to stop the bleeding in time for the next round, leading to a stoppage — and considering the damage already done to Rocky's face, a professional referee and/or ringside doctor would likely have stopped the fight long before such a move was necessary. In Gambina's hilariously terse 2004 interview with fan site Total Rocky, he chalked the moment up to "dramatic license."

Going the distance

While Chuck Wepner stood up to Muhammad Ali only to be knocked out in the final seconds of the fight, Rocky goes the distance with Apollo Creed. Both men are knocked down in the course of the dramatic, world-changing fight, but both end the final round on their feet, and the final victory is awarded by the judge's scorecards. While contemporary audiences would have needed no explanation as to why the fight lasted 15 rounds, modern-day audiences may be confused by this detail. It isn't Hollywood exaggeration; for most of the 20th century, the standard length for male championship boxing matches was 15 rounds. It wasn't until 1982 that the current 12-round standard began to be adopted.

As sadly often happens in sports and in boxing particularly, it took a tragedy to bring about reform. In 1982 American boxer Ray "Boom Boom" Mancini faced Korean fighter Kim Duk-Koo in Las Vegas (via Inquirer.net). It was Kim's first U.S. fight, and would sadly be his last. A brutal knockdown by Mancini in the 14th round put Kim on the canvas; after being brought back to his corner, he collapsed and was rushed to a hospital, dying in a coma several days later. A month after the fight, the World Boxing Council announced that it would reduce its championship matches to 12 rounds (via The Washington Post), and by 1988 all the other major sanctioning bodies had followed suit (via The New York Times).

Yo Adrian

The final bell rings and Bill Conti's iconic score kicks in as officials and each fighter's corner men rush the ring. Rocky's love Adrian (Talia Shire) pushes her way through the crowd as he bellows her name from the ring, and between the music, the noise of the crowd, and Rocky's shouting, it's barely audible that the judges have awarded Apollo the win by split decision. It hardly matters, though; the real victory is that Rocky proved to himself, to Adrian, and to the world that he has the heart of a champion. As the marble-mouthed fighter and the pet store clerk exchange tear-filled declarations of love and embrace in the center of the ring, the film fades to black.

That wasn't always the ending, however. Originally the film concluded on a more muted note, with Rocky and Adrian leaving the stadium together, quietly hand in hand, Rocky still in his trunks. In a 2021 interview with Yahoo! Entertainment, producer Irwin Winkler told how the film was screened for a small preview audience of friends, who were energized by the final fight scene, only to be brought down by the original lowkey end scene: "That whole high that we were getting from the audience suddenly dipped down to a real low." In the end, the final moment of Rocky and Adrian walking together may have been cut from the film, but it lived on as the inspiration for the film's theatrical poster.

The fight continues

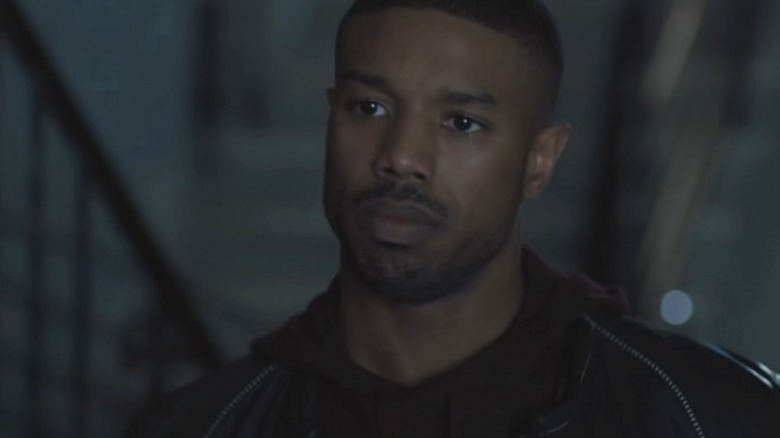

As Rocky and Apollo clinch in the fight's final moment, Apollo says, "Ain't gonna be no rematch." Rocky agrees; "I don't want it." But a $100 million at the box office and two Oscars can be very persuasive, and three years later the band got together (minus Avildsen; Stallone took over directorial duties himself) for 1979's "Rocky II." As Rocky struggles with his post-fight fame, pressure mounts to face Apollo once again in the ring; when they finally reunite to settle the score, it's Rocky who comes out on top and with the heavyweight belt. Then, 1982's "Rocky III" has the complacent champ claw back to glory after losing his title to the vicious Clubber Lang (Mr. T). "Rocky IV" goes all-in on the patriotic feeling that the first film lampooned, sending Rocky to the Soviet Union on a revenge mission against the inhuman Ivan Drago (Dolph Lundgren), while "Rocky V" in 1990 brought Avildsen back to direct what was supposed to be a back-to-basics sequel but ended up being the nadir of the series.

At a certain point, the number of "Rocky" sequels became a running joke, and the series was put on the shelf until the 2006 legacy sequel "Rocky Balboa," which had a 60-year-old Rocky reconciling with his son (Milo Ventimiglia) while lacing up the gloves for an exhibition match against the current heavyweight champ (real-life boxer Antonio Tarver). The film earned good reviews (via Rotten Tomatoes), but it wasn't until Ryan Coogler's 2015 reboot "Creed" that Rocky found a place in the 21st century. The film, starring Michael B. Jordan as Apollo's illegitimate son, earned Stallone his first Oscar nominations since the first film in the series (via IMDb).

Bad Blood

The "Creed" series has Rocky training young Adonis (Jordan) while dealing with his own issues. The first film gives him a cancer diagnosis, while 2018's "Creed II" finds him once again on the outs with his son (Ventimiglia, returning for a cameo). Shortly after that sequel's release, Stallone posted a video on his Instagram page announcing that he was officially retiring the role of Rocky Balboa, more than 40 years after his split decision loss to Apollo Creed. "My story has been told," he told a gathered group of "Creed II" cast and crew members (via Vanity Fair). "There's a whole new world that's gonna be opening up."

While at the time this appeared to be a magnanimous passing of the torch to Jordan, Coogler, and "Creed II" director Steven Caple Jr., in the years since, details have emerged painting a more fraught behind-the-scenes picture, especially as interest in the series revived upon the release of the trailer for 2023's "Creed III." In July 2022, when it was announced that Winkler and his son David were preparing a new "Rocky" spin-off based on Ivan Drago, Stallone took to Instagram once again and accused the Winklers of being vampires feasting on the corpse of Rocky (via Deadline). Then, in a November 2022 interview with the Hollywood Reporter, Stallone clarified that he had no role in the production of "Creed III" and was disappointed in the apparently darker direction the film takes with the "Rocky" mythology: "I just feel people have enough darkness."