The Son Review: Falls Short Of The Father's Triumph

- Vanessa Kirby is the film's one saving grace - the only performance (and character) that feels authentic.

- An emotionally manipulative look at depression that feels divorced from reality.

- An ensemble of inauthentic performances.

You'll struggle to find a cinematic study of mental health conditions more concerned with triggering an emotional response from the audience over sensitively depicting their harsh realities than director Florian Zeller's "The Son," which screened at London Film Festival.

In retrospect, it's a surprise that his previous film, 2020's award-winning "The Father," wasn't criticized for the same reason; it was an appropriately punishing watch, enveloping viewers in the hostile mindscape of Anthony Hopkins' elderly patriarch during the waning days of his battle with dementia.

But where that movie was effective in its approach, submerging its audience into its lead character's headspace via ingenious production design and an elaborate non-linear structure, "The Son" is much more straightforward, so uncomfortably melodramatic in its study of clinical depression it might make you wonder if "The Father" would also feel like a TV movie of the week if told more conventionally.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

A depiction of depression which leaves a foul taste

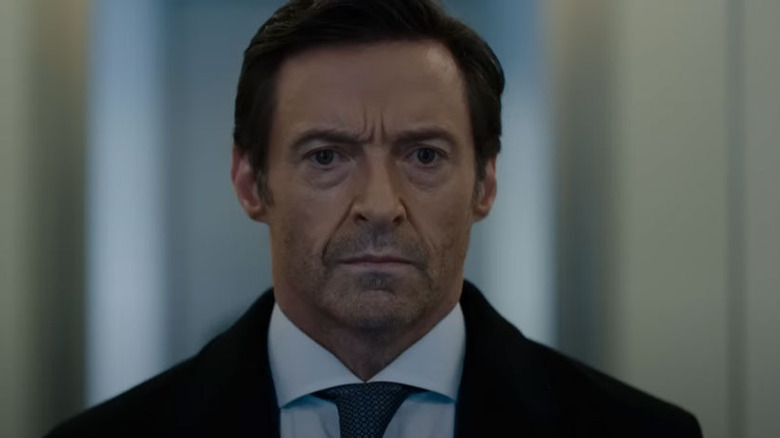

Like Zeller's prior film, this has been adapted from his acclaimed stage play of the same name — although, unlike his previous directorial effort, the acclaim from the stage has not translated to the screen. Hugh Jackman stars as well-regarded lawyer Peter Miller, whose personal life and career couldn't be in a better place: with new wife Beth (Vanessa Kirby), he's recently welcomed a baby, and he's in discussions to land a dream job running a presidential campaign in Washington. But his blissful home life (and by extension, his professional aspirations) are about to be dealt a blow after a meeting with his ex-wife Kate (Laura Dern), who has custody of his teenage son Nicholas (newcomer Zen McGrath). Suffering from clinical depression and suicidal tendencies, which Kate believes are a fallout from the parental divorce a few years prior, she recommends he move in with Peter, start attending a new school, and get his life back on track. Naturally, their lack of understanding of the severity of the situation, despite several obvious signs, has dramatic consequences for the family unit.

Much like a horror movie designed to make audiences yell at the screen not to enter an obviously haunted house, much of "The Son" feels cynically designed to manipulate by having its parental characters follow through with the worst decisions at every possible turn. Neither Peter nor Kate seem to comprehend the ramifications of severe mental health conditions, which frequently makes them seem like quasi-surrogates for Zeller and co-screenwriter Christopher Hampton (who previously translated the play on which the film is based into English), who jointly simplify teenage depression into its most melodramatically palatable form throughout. This leads to several sequences in which its two leads ignore the glaringly obvious signs of their son's illness, all of which are written in a fashion likely alien to those who have first-hand experience of the condition: clinical depression as a dramatic construct the audience are aware of, but the characters frequently overlook or downplay, yielding disastrous consequences. It is every bit as tastefully handled as it sounds.

As much as the chief responsibility for the mishandling of such weighty subject matter falls at the feet of Zeller and Hampton, the over-cranked performances from the ensemble don't exactly help elevate the material. Hugh Jackman, who was widely assumed to be the best actor frontrunner until the moment people first saw the film, has the near-impossible task of making an empathetic figure out of a man so self-absorbed he can't communicate with his own teenage son in the way he desperately needs to. There's an iteration of this film in which the struggles of Nicholas are communicated more effectively through the screenplay, where they appear less obvious on the surface and you can understand why both parents frequently struggle to see them, something which would feel far closer to home for those who have lived with or know those who have struggled with mental health conditions. Watching this a few days after Charlotte Wells' excellent directorial debut "Aftersun" really highlighted how lacking "The Son" was in this regard.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

It chooses emotional manipulation over sensitivity

Instead, the soap opera-style depiction of depression feels divorced from reality, which has drastic effects on every performer in the ensemble; both Jackman and Laura Dern's Kate feel like aliens with no grasp on basic human emotions due to how they keep conveniently missing every sign telegraphed painfully (not to mention unbelievably) to the audience. Only Vanessa Kirby's performance feels tethered to something approaching reality — her relationship with her stepson is deeply complicated, fearing that his emotional state makes him a threat to her newborn baby. The way the character's fear is driven by a prejudicial lack of understanding is the only time the film gets close to unpacking the ways in which those with depression are still viewed by many — a glimpse of authentic insight within a film that otherwise opts for the cheapest emotional manipulation at every turn. But this never remains in focus for as long as it should. It becomes increasingly apparent Zeller is more interested in breathing life into Jackman's character than making his son more than an outdated, insensitive archetype. This is most apparent in the way it attempts to draw parallels between Peter and his own father, an uncaring politician played in an excruciating cameo by Anthony Hopkins, to broadly highlight how the curse of being an absent parent is handed down between generations.

Since the film premiered in Venice to an overwhelming shrug of the shoulders from the press corps, the main talking point has become just how bleak the film is, building up to a climax so miserable it's become semi-notorious within critical circles. I find it hard to buy into the description of the film as bleak, as that would imply it has done an effective job of conveying the brutal nature of living with depression. Everything within the third act of "The Son" has been telegraphed from its earliest moments to the extent that you can imagine the ghost of Anton Chekhov repeatedly pointing at the screen every few minutes, Leonardo DiCaprio in "Once Upon a Time in Hollywood" style, by the time we approach the upsetting pay-off. It seems cheap to describe such a climactic development in this way, but Zeller's treatment of the subject matter feels designed to make audiences cry first and foremost. There's nothing that feels authentic here, just cynical emotional manipulation which feels disrespectful to those who have first-hand experience of what the film is depicting.

"The Son" isn't just a disappointing follow-up to "The Father"; it's an emotionally hollow exploration of subject matter which deserves more carefully considered treatment onscreen. It's a relief critics are seeing it as the empty vessel it is, and hopefully, audiences will follow suit.

"The Son" premieres in select theaters on Friday, November 25, and will release nationwide on January 20, 2023.