The Untold Truth Of They Live

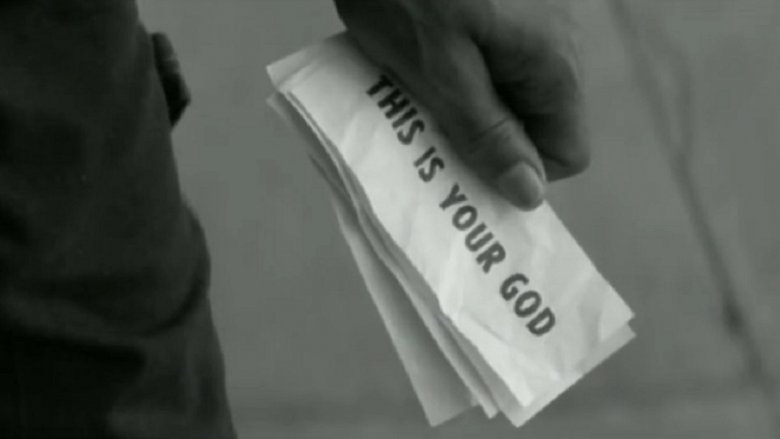

As John Carpenter's 1988 sci-fi/horror opus They Live approaches the 30th anniversary of its release, it's amazing to note how relevant the film's themes continue to be. A scathing indictment of capitalism and the culture of greed masquerading as a B monster movie about invading aliens, They Live featured professional wrestler "Rowdy" Roddy Piper as Nada, a homeless laborer whose world is turned upside down when he finds a box of special sunglasses that allow the wearer to see the truth. Namely, that subliminal messaging prompting us to "CONFORM" and "OBEY" is all around us, that our complacency in the face of exploitation and injustice is literally being beamed into our brains, and that many members of upper-crust society are not at all what they seem.

The film is one of Carpenter's greatest works and even more vital now than it was 30 years ago. As such, we're taking a close look at some of the interesting details that even hardcore Carpenter fans may not know about They Live.

Based on a short story

Carpenter's inspiration came in the form of a little-known short story from 1963: Ray Nelson's "Eight O'Clock in the Morning," which likewise featured a character named Nada who awakens to the fact that the world is secretly being run by snakelike aliens who control humanity's thoughts and actions. While many of the story's elements — such as the ubiquitous subliminal messaging, and the aliens' use of television as their means of keeping the public hypnotized — would later make it to the screen, Carpenter wisely added a few tweaks to the plot while omitting some of the story's more random details.

For instance, the literary Nada is told by one of the aliens — referred to as "Fascinators" — that his heart will stop at (wait for it) 8 o'clock in the morning, giving him only a limited amount of time to unravel their plot. This race-against-time element isn't present in the film, nor is the ridiculous means (a hypnotist's act) by which he wakes up to the alien presence. Instead, Carpenter uses the aliens' covert war against a small human resistance to add tension, and introduces the plot point of the sunglasses — manufactured by the resistance, of course — as a more sensible way for Nada to discover the truth. Nelson's story was adapted faithfully into a 1986 graphic novel titled Nada, which likely served as further inspiration for Carpenter to bring the story to the screen.

The mystery of John Nada

As in Nelson's story, Piper's Nada is so named because he is meant to be a blank slate, an everyman; he is given very little backstory and is never referred to by name in the film even once. Only his last name appears in the credits, although Carpenter has since let slip that the character's first name is John — and that he indeed has an extensive backstory, even if the filmmaker himself doesn't know what it is.

Speaking with Yahoo! Entertainment, Carpenter revealed that only one man knew what unfortunate circumstances befell the homeless Nada before the events of the film: Roddy Piper. "I had [Piper] work out some [backstory] of his own and never tell me," he says. "I didn't need to know, as long as he knew ... I believe his wife was killed by unintentional acceleration, which is something that happens with cars." Piper never went on the record to elaborate before his untimely death in 2015, but perhaps it's good that he didn't; it means that Nada will always remain as he was intended — a complete mystery.

The famous fight scene

At nearly six minutes long, the brutal alleyway fight scene between Nada and fellow homeless laborer Frank Armitage (Keith David) over the latter's refusal to put on the special sunglasses is one of the most celebrated in film history. It's been endlessly referenced, quoted and parodied (most notably via a nearly shot-for-shot re-creation in the South Park episode "Cripple Fight"), and it's inevitably brought up as a point of comparison every time a potential new "best fight scene of all time" emerges. The scene was conceived by Carpenter, Piper, and veteran stunt performer and coordinator Jeff Imada, who has worked on a laundry list of classic action films from Lethal Weapon to Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, with the idea of creating a fight scene that would be totally singular.

"I wanted to do this unique fight," the director said in a documentary, "and I brought Jeff Imada in, and brought Roddy in, and we all sat around and talked about ... what would make a fight unique, in the sense that you haven't seen anything like this. And I wanted to utilize some of Roddy's professional wrestling techniques and knowledge." David related how this knowledge helped to make the fight more realistic: "He teaches me about this stuff, reactions, when you get punched and when you get hurt." Piper's assessment of his costar's contribution to the scene was characteristically straightforward. "This guy," he told an interviewer, "hits like a mule."

The artist who rode it to fame

Artist Shepard Fairey, who designed the iconic HOPE poster which became a central (if unofficial) aspect of Barack Obama's successful 2008 presidential run, just might have Carpenter to thank for his career. In the late '80s, Fairey became somewhat well known for his "Andre the Giant Has a Posse" street art, which featured an image of the iconic wrestler. By the mid-'90s the concept would morph into a work that become pervasive, appearing on stickers and posters seemingly everywhere. It's known as "Obey Giant," and it's simply a stylized closeup of the wrestler's face with the caption "Obey."

The image kick-started Fairey's career, and he readily admits that he was struck by the imagery in Carpenter's film, as well as its underlying message. In a video posted to YouTube in 2011, Fairey remembers picking up a copy of the film on videocassette in 1993, and being blown away: "The film ... has a rather profound concept, which is that people don't realize they're being manipulated," he says. "The ads, instead of saying 'Vacation in Tahiti,' say things like 'consume,' 'watch television,' 'submit,' 'obey' ... Not only did the film impact me conceptually ... but also graphically." For his part, Carpenter says he's never met Fairey, implying that he doesn't mind being the source of his inspiration but that it might have been nice to be asked.

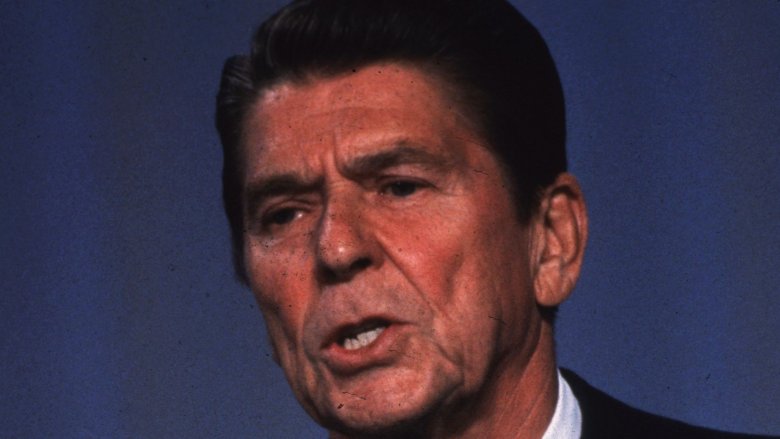

Sticking it to Reagan

If Carpenter intended They Live to be a ballistic missile lobbed at '80s materialism and excess, he's never been shy about who he ultimately saw as the symbol of that excess: President Ronald Reagan, whose economic policies widened the gap between the rich and poor and encouraged unchecked greed in the financial sector. Speaking with the magazine Starlog around the time of the film's release, Carpenter was clear on this point, calling the president and his cabinet "a bunch of crooks" and recalling his glee when the Iran-Contra scandal began unfolding in 1986. In the years since, Carpenter has been happy to elaborate on his contempt for ol' Ronnie whenever given the opportunity.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 2013, Carpenter said that under Reagan "a lot of the ideals that I grew up with were under assault, and something called a 'yuppie' came into existence, and they just wanted money. And so by the late '80s, I'd had enough, and I decided I had to make a statement ... and that's They Live ... I just love that it was giving the finger to Reagan when nobody else would." He went on to say that the studio wanted him to have his aliens eating people like proper monsters, but that he had insisted that money and resources should be their only motivation.

The cast was set from the beginning

When it came time for Carpenter to cast his film, there were few tough decisions to be made; he had envisioned Piper and David as his two leads from the beginning. The unconventional choice of Piper, a professional wrestler with limited acting experience, ended up being a perfect fit for Nada. "Unlike most Hollywood actors, Roddy has his life written all over him," the director told Starlog (via USA). "He has been hit so many times ... he is definitely not a pretty boy. He's the toughest guy I've ever met."

As for his costar, Carpenter was impressed by David's performance in his 1982 horror masterpiece The Thing, and wrote the part of Frank with the actor in mind. "Keith is such a fabulous actor," he says. "[He's] a big guy, and I needed a big guy to fight Roddy Piper. I also needed somebody who wouldn't be a traditional sidekick but could hold his own." He says that the two became friends on set and that "after they had kind of beaten each other silly, they became real, real close friends."

But could it happen in real life?

In the same interview, Carpenter offered a surprising anecdote that may make you wonder just how far-fetched — or not — the film's premise really is. The scene in which Nada discovers that all of the pages of every magazine on a newsstand are plastered with the aliens' subliminal messages was shot on location on a Los Angeles street, and the director was stunned at the reactions of passersby — or rather, the lack of any reaction — to the fact that their local newsstand now seemed to exclusively stock stark white magazines screaming ominous slogans in bold black print.

"People who didn't see the cameras walked by on the street," he says. "They literally paid no attention when the covers said 'obey.' They looked for a moment and moved right on. We had a big sign on a building which said 'conform.' People glanced up at it and didn't give it a second thought. It was hard to believe."

Screenplay by Frank Armitage... but not really

Sharp-eyed viewers may have noticed that the screenplay is credited to Frank Armitage, which happens to be the same name as Keith's character. This, of course, is a pseudonym. Carpenter wrote the screenplay but felt it was enough of a collaborative effort (with then-girlfriend and future wife Sandy King and Piper as well) to not take sole credit.

There was another reason Carpenter shared credit as well. As he told Entertainment Weekly in 2012, he wasn't comfortable with it: "It was a reaction to seeing my name all over these movies," he said. "I think the height of it was Christine. It was like, John Carpenter's Christine, directed by John Carpenter, music by John Carpenter ... What an egotist!"

The choice of pseudonym, by the way, reveals that, like his buddy Stephen King, Carpenter is a lifelong fan of classic horror author H.P. Lovecraft. The name is a reference to Dr. Henry Armitage, a character in The Dunwich Horror, one of Lovecraft's best-known works.

He's all out of bubblegum

Soon after Nada's unpleasant discovery about the world around him, he has a scuffle with a pair of cops (one of whom is an alien) and manages to get away with one of their shotguns by ducking into a building, which happens to be a bank. As the patrons react to Nada, still brandishing the weapon, he takes stock of a number of alien interlopers in the room, manages the tiniest of grins, and utters one of the most badass lines in film history: "I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass ... and I'm all out of bubblegum."

The line has become so embedded in popular culture that even those who haven't seen the film have probably heard it somewhere, and it wasn't Carpenter's creation — it came directly from Piper. In the same EW interview, he says, "Roddy came up with that. Traveling all around the country wrestling different people, those guys come up with a lot of stuff to hype matches in interviews. They have to come up with one-liners. Roddy had a book full of them that he carried with him ... he gave me the book when I was writing the script and that was the best one in there." It's easy to imagine Piper using the line in his "Rowdy" wrestling persona, where it may have been relegated to some long-forgotten interview in a wrestling magazine; putting it in Nada's mouth instead was probably the right choice.

It's all about economic inequality

Carpenter's choice to make his heroes down-on-their-luck homeless men up against alien invaders who all seem to be rich yuppies (and, more frighteningly, politicians) starkly underlines the film's ultimate message, which should be even clearer today than it was 30 years ago. The film is a parable — Carpenter has gone so far as to call it a documentary — for the exploitation of the poor by the upper class and an indictment of the rampant economic inequality that makes it possible. The director made sure to emphasize the gulf between rich and poor visually in the film, such as the opening scenes in the shantytown, which were shot in an actual homeless settlement (with its residents paid a day's wages to act as extras) framed against the glitzy high-rises of downtown L.A. in the background.

"It's morphed into something really bizarre," he told Yahoo! "The same problem — unrestrained capitalism — still exists. Listen, I'm a very happy capitalist. I love my country. I love the system that we're in, but not without some restraints on it ... the '80s never ended. The mentality that the '80s bred is really alive and well — that's the part that's so bad."