The Ending Of Wendell & Wild Explained

"Wendell & Wild" is, well, a wild ride of an animated movie. Out on Netflix just in time for Halloween, this spooky, punk-tinged stop-motion adventure is a collaboration between Henry Selick (of "The Nightmare Before Christmas" and "Coraline" fame) and Jordan Peele, who co-wrote the screenplay and stars alongside Keegan-Michael Key. The film is lovingly made, aesthetically in its own league, a little overwrought with a multi-tentacled story, and more complex than the vast majority of animated films in its subject matter and themes. Its blend of slightly bawdy humor, emo moodiness, and social justice issues means it's probably not for small children, and even adults might have some questions about what, exactly, is going on in this unique world Selick and Peele created.

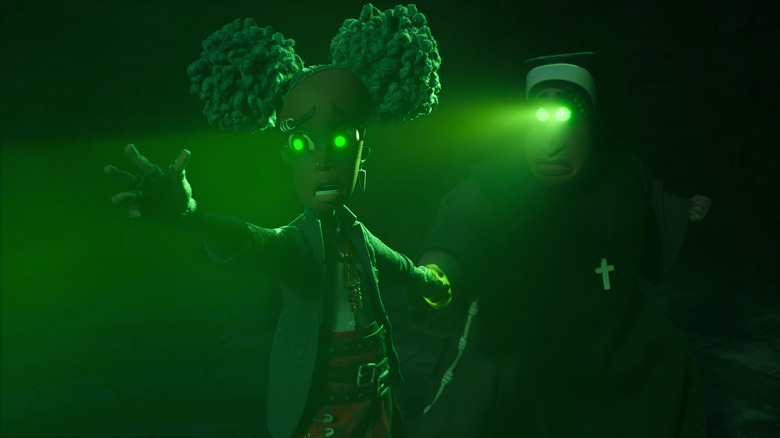

"Wendell & Wild" sees its protagonist, Kat, journey from her dilapidated hometown of Rust Bank to the creepy, under-attended Catholic school, with a few pitstops in an unnamed underworld where demons find amusement in torturing souls. A shady corporation wants the town for its latest project, which essentially amounts to a school-to-prison pipeline. The town council is investigating them for murder. And a nun and a janitor turn out to be demon hunters, well-acquainted with the Hell that lies just beneath their feet. And that's to say nothing of rooftop art projects, possessed teddy bears, and hair cream that can bring the dead back to life. There's a lot going on in "Wendell & Wild," especially for a movie that only runs 105 minutes, but we can help you figure out what happens and what it all means.

The dead parents trope gets a more realistic remix

Like countless kids' movies that have come before it, "Wendell & Wild" starts with the traumatic death of a child's parents. Seven-year-old Kat bites into a candy apple, a two-headed worm pops out, and her scream sends the family car careening off of a bridge and into the water below. Kat's mom, Wilma, tells her to take a deep breath and manages to free her from the vehicle before it sinks. Theoretically, this sets Kat — now without guardians to protect her — on a hero's journey in the vein of "James and the Giant Peach" (also a Henry Selick movie). But her burden isn't merely an obnoxious unfair aunt — when we catch up with Kat as a 13-year-old, she's being released from a juvenile detention center.

While the death of her parents as an inciting incident is arguably cliché, the way "Wendell & Wild" handles the aftermath of the tragedy is realistic and grounded compared to the average supernatural orphan story. Kat grew up believing she was responsible for the accident. She ended up in foster care and group homes, and was eventually incarcerated (that Kat is Black carries even more poignancy, as Black youth are disproportionately committed to detention centers). She's full of unresolved angst and is clearly self-destructive: Over the course of the film, Kat has to overcome very real emotional and systemic issues.

Klax Korp stages a hostile takeover

Before the car accident, a company called Klax Korp was attempting to buy her parents' root beer brewery, which employed a large number of Rust Bank residents. After their deaths, a mysterious fire leveled the brewery, killing all the workers inside. Many residents suspect arson, including Marianna (Raúl's mom and member of the town council that has been voting down Klax Korp's planned private prison for years), but there are no witnesses to testify. From conversations between Kat and Siobhan, we can tell that the Klaxes have already made a fortune from erecting similar prisons elsewhere. They insist their services are holistic and rehabilitative, but really, they're ultra-low cost, providing poor conditions and low wages as the Klaxes keep the profits. They use intimidation, corruption, and obscene wealth to get their way.

That "Wendell & Wild" chooses to make owners of private prisons the villain is no accident. Nor is it merely a coincidence that Klax Korp chose Rust Bank as the site of their new project. The implication is that Klax Korp targets economically depressed towns, like Rust Bank, assuming they won't get pushback the way they might if they tried to build a prison facility in an upper-middle-class enclave. They're preying on residents' desperation and counting on their apathy. We see that the corporation has forced out the types of locally owned businesses, like movie theaters and family-owned restaurants, that make a community vibrant. Blight is all that's left in their place.

Kat makes a deal with some devils

Kat already feels like an outcast at Rust Bank Catholic. In part, she uses her bad girl status to keep people at a distance, but she soon finds out that something deeper and darker is going on. When Sister Hellie presents a mimic octopus to the class, Kat walks to the front to see the creature. It turns demonic, and Kat feels an unexplained burn on the back of her hand. Hellie scurries her out into the hallway and inspects the wound, which looks strangely like a set of teeth. Her mark represents in many ways her trauma, the feeling of being permanently scarred or damaged because of her past.

Simultaneously, two purple devilish brothers — Wendell and Wild — see Kat in a hair cream-induced haze, and Wild can feel her hand. Turns out, she's more than a misfit: She's a Hell Maiden, a human with the ability to bring entities from "downstairs" up to the world of the living. This experience will mark her as Wendell and Wild's Hell Maiden. The brothers want to reach the surface because they have construction plans of their own: Instead of their devil dad's Scream Faire, they want to build a much more pleasant Dream Faire. But first, they need Kat to work her nefarious magic.

Except she wants something in return. Having realized that the hair cream can revive the dead, they promise to bring back her parents if she recites a spell with Bearz-a-bub, an extremely ominous stuffed animal. Kat agrees when they point out she has nothing left to lose.

She doesn't want friends, but gets some anyway

That Kat pushes people away is another completely plausible personality trait of someone who's been through the trauma that she has experienced. When she gets to RBC, she meets a group of three girls she calls "the Poodles," led by Siobhan Klax. She makes the acquaintance of Raúl in class, a trans boy who used to be one of the Poodles and who has a talent for art. Both the clique and Raúl want to befriend Kat, but she resists. Raúl accompanies her on her mission to summon Wendell and Wild, and when Father Bests and the Klaxes forbid the demon brothers from holding up their end of the bargain and raising Kat's parents from the dead, it's Raúl who steals the cream and does it himself.

But Siobhan proves herself to be a true friend to Kat, too. Once Kat confronts Siobhan about the nature of her parents' industry, she joins the protests against Klax Korp, much to her mother's dismay. Neither Raúl nor Siobhan judge Kat for her criminal record, her thorny demeanor, or even the fact that she's a Hell Maiden, once they see that she's gotten involved with creatures from the underworld. The film is a lesson in learning to trust that people will love you for who you are.

She's not the only one who's special

Another figure who steps in to help Kat and Rust Bank is Sister Hellie, who has more in common with the troubled teen than Kat initially understands. Since the Catholic Church isn't portrayed in the best light — dishonest and money-grubbing Father Bests stays in cahoots with the Klaxes even after they fatally club him in the head — there's an air of mystery as to whether Sister Hellie has Kat's best interests at heart. When she magically disappears and can travel through floors, we get confirmation that Hellie's special in some way, too.

It's revealed that Hellie and the janitor, Manberg, have been hunting demons at RBC for quite some time. He's got a collection of Wendell and Wild's siblings in jars on his shelf. Hellie's own name is a clue that she was once a Hell Maiden who probably brought some of these demons to the surface world with Bearz-a-bub, but she's since learned how to break the bond between human and hellion.

If the hand mark is symbolic of past trauma, we can surmise that Hellie's past is similar to Kat's. While other adults may have taken her in for financial incentives, in a vision at the film's conclusion, Kat tells her parents that she and Hellie are "doin' stuff" together — including opening a school with the goal of actually "breaking the cycle."

Kat faces her real demons

Kat's mark seems to be preventing her from acting of her own volition. When she swears allegiance to her demons, she loses some of her free will. Thankfully, Manberg and Hellie know what to do. Manberg first tries to suck the demon influence from her with the same device he uses to trap demons, but Hellie sees that the influence is too strong. The two Hell Maidens have to be bound together in blood.

With their hands sliced and wrapped, Hellie shows Kat the monster that's grown out of her fear, pain, and repressed memories. She's literally chained to this monster, and at first, it controls her like a puppet. It slaps her around, then punches her, then raises her into the air and drops her on the floor. Hellie tells Kat that she can only stop the monster by owning the memories. We see her parents' death, an incident in which she pushed a boy down the stairs, and the day she was sentenced to juvenile detention. Kat finds the bravery to face these thoughts unflinchingly, and the steampunk-like monster begins to fall apart. At one point, she's sucked into its dimension, where what remains of the monster looks small and scared. Rather than put it out of its misery, Kat hugs it, and her painful past becomes a part of her.

Through this process, Kat is given the gift of foresight. For practical purposes within the narrative of the film, this gives her the ability to see into the future. But it also reflects the fact that having worked through some of these issues, Kat can finally envision the future with a sense of hope and optimism.

Greed is the monster

"Wendell & Wild" intentionally leads audiences to believe that the demon brothers and their giant father, Belzer, are the big bad villains who Kat will eventually have to defeat during the climax of the film. But even young viewers probably guess early on that the Kluxes in particular and greed in general were the real sources of evil. In one of Kat's memories, we see that the foster parents who took her in only did so for the money, and that the children at the home weren't treated well. Father Bests at RBC has accepted her into the once prestigious school because it needs money, since there are too few affluent parents to send their children to private school in Rust Bank, and the building itself has fallen into disrepair. But like the foster families, he has no intention of providing Kat with the best possible services.

Wendell and Wild — who are demons — lie and scheme. They're willing to break their pact with Kat if it means they can achieve their dream of building their own afterlife amusement park. But the epitome of greed is Klax Korp. A model shows just how they expect to exploit what's often called the school-to-prison pipeline. Figures of children fall from a poorly run private school directly into a poorly run private prison, as Rust Bank becomes a factory of lost souls from which only the Klaxes profit. The lack of resources that go to the institutions of economically depressed areas, such as schools, and the clear conflict of interest related to the owners of private prisons being involved in local politics are serious, pressing issues in America. It's ambitious that "Wendell & Wild" takes them on.

Demons have dysfunctional families too

In addition to socio-economic concerns, "Wendell & Wild" is also interested in mental and emotional health. Though it's not the ley resolution to the main plot line, the way Buffalo Belzer grows as a father figure is another subverted expectation. We might think, once the enormous Satan figure emerges from below the Earth's crust, that he's going to be another villain that Kat and her cohorts will have to defeat. After all, he's looking for Wendell and Wild because he's miffed they've come to the surface without his permission. But as it happens, all those demons Manberg caught in jars were also escaped children of Belzer, discontent with the menial jobs they were given in his version of Hell. The whole time, he thought his children ran away and never came back, and (like Kat) grew ever more callous, probably in an effort to protect himself from further pain. When he sees they'd been captured and that he has a second chance to build a better relationship, he re-evaluates his iron-fisted parenting style.

There's a funny exchange between demon hunter Manberg and Belzer in which the former insists upon being called Manberg the Merciless, but the latter, happy to have his family back together, calls him Manberg the Merciful. The second moniker is definitely more accurate. Belzer sees that he hasn't let his children individualize, and goes back to his realm promising Wendell and Wild they can design the next amusement park.

Kat and friends use necromancy for good

The resolution to the main plot all goes back to the brewery we saw at the beginning of the movie. The Klaxes and Father Beats convince Wendell and Wild to use the cream to raise long-dead council members, who would then vote in favor of the sale of the brewery to the prison corporation. The zombies win the vote six to five, and bulldozers are readied to raze the town.

But when Father Bests dies a second time, everyone realizes the hair cream's effects are temporary. There's only a drop or so left, and Kat considers using it to spend more time with her parents. But although they're thrilled to have had the opportunity to see their daughter again, they encourage her to use the hair cream for the greater good, defeating Klax Korp once and for all. What Marianna needs are witnesses. Raúl uses the remaining cream to revive three victims of the brewery fire who can testify to the fact that it was not an accident, but arson, and that the Klaxes were responsible for it. They're arrested just before the bulldozers driven by zombies are able to knock over the water tower.

There's something coy and fun about the fact that a troubled goth girl, a trans boy, and some demons and zombies save the day in "Wendell & Wild." The film's final message is two-fold. First, Kat is able to assure her parents that she'll be okay, which is all any parent wants to know about the world they're leaving for their children. Second, Kat's vision of the future is of a culturally and economically healthy Rust Bank that's taking care of all of its people, not just the wealthy elite. The theaters and restaurants are reopening, as are the schools, and people are buying and fixing up houses again. In the end, "Wendell & Wild" is about the relationship between the well-being of individual citizens and their communities.