Things That Happen In Every National Lampoon's Movie

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 1970, Harvard graduates Doug Kenney and Henry Beard took their acclaimed undergraduate publication, the Harvard Lampoon (home of the popular "Lord of the Rings" parody "Bored of the Rings") and spun it into National Lampoon Magazine. Like its less-vulgar contemporaries, Cracked and MAD, National Lampoon established a foothold in American humor in the 1970s, leading to radio shows, theater productions, books, feature films — and at least one dog who was nearly murdered.

The movies began with "Animal House" in 1978 (not counting the TV film "Disco Beaver From Outer Space"), a pretty good start, as the Kenney-written, John Belushi-starring film became a phenomenon. Eventually, the "Lampoon" stamp got a bit watered down, particularly after the 1980 death of Kenney; rather than being "spin-offs" written by the magazine staff and showcasing actors who had performed on "The National Lampoon Radio Hour" (like Chevy Chase) or the stage show "National Lampoon's Lemmings" (like Belushi), the "National Lampoon's" moniker would became a bankable star itself, licensed to (typically raunchy, teen-focused) films for a fee.

Through company shifts, the disbanding of the magazine in 1998, and multiple changes in ownership, the "National Lampoon" has remained recognizable, if no longer an indicator of guaranteed laughs — as exemplified by films like 2011's "National Lampoon's 301: The Legend of Awesomest Maximus," 2006's "National Lampoon Presents Electric Apricot: Quest For Festeroo" or "National Lampoon's Van Wilder: The Rise of Taj."

All together, over 30 movies with the Lampoon brand etched above their title have been released in the 44 years since "Animal House," with 2018's "A Futile and Stupid Gesture" memorably depicting its origins, shortcomings and enduring legacy. As fun as "Loaded Weapon 1" and the original "Van Wilder" may have been, below is a look before the "Jake's Booty Call" days, when the original 1978 – 1989 films succeeded in not only making some great films, but also establishing a unique flavor all its own.

Satire of Contemporary Lifestyles

Just as National Lampoon Magazine earned its stripes by satirizing hot button issues of contemporary America, the flagship's movies set out to do the same. Beginning with "Animal House" in 1978, which mocked the perverse masculinity and flatulent raunchiness of college fraternities, it was clear that the Lampoon and its writers had a knack for knocking parts of the real world down a few pegs.

Subsequent films like 1982's "Class Reunion" and 1984's "Joy of Sex" wouldn't make nearly as much money, but would tout "the makers of 'Animal House'" tackling high school culture and virginal values, with the latter part of an '80s sex comedy movement that would eventually be revived by "American Pie." 1982's "Movie Madness" felt more akin to the Zucker/Abrams/Zucker classic "Kentucky Fried Movie" or Ken Shapiro's "The Groove Tube," this time with the Lampoon making fun of sketch comedies, variety specials, and, ultimately, itself. None of those films did terribly well; the latter sits at 0 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, with critic Scott Weinberg commenting: "Leave this one as history has intended: unknown, forgotten, and detested by the unfortunate few who've actually seen it."

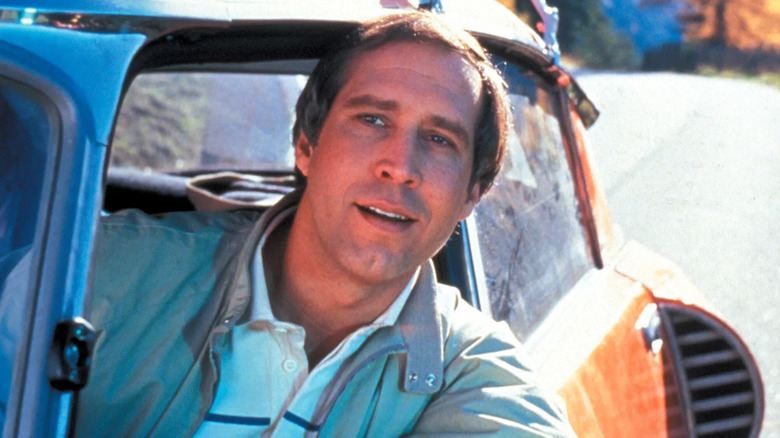

No less than John Hughes would save the day beginning in 1983 with "Vacation," based on childhood memories he originally wrote for a vacation-themed issue of the "Lampoon" magazine. After Hughes adapted his article into a screenplay, Chevy Chase and director Harold Ramis rewrote it to tell the story from the father's point of view rather than that of the 12-year-old son, and a comedy franchise was born.

That original Griswold adventure would be followed by 1985's "European Vacation," and 1989's "Christmas Vacation," as Lampoon began to re-focus its gaze from frat houses to the nuclear family. Although fraternity and road trip comedies aren't nearly as ubiquitous as thy were in the '80s, now and forever they all owe a debt to "Animal House" and the "Vacation" series.

Recurring Actors

Far more than today, movie stars were still a big deal in the '80s. Almost regardless of plot, hits were made by what names were put above the title.

Fortunately for the Lampoon, it held long-established connections with some of the biggest comedic names of the era, and these films were also adept at minting new stars. Belushi, Chase, Ramis and others had come up with the "Radio Hour," "Lemmings" and the magazine, and emerging stars like John Candy, Eugene Levy and Kevin Bacon all had key roles in those early Lampoon films.

But far and away, the most prominent featured player was Chase, who'd headline every "Vacation" movie. Chase's ties to the Lampoon went as far back as the origins of the magazine, joining "Radio Hour" in 1973 before becoming the face of "Saturday Night Live" a few years later. He had a rapport and friendship with Lampoon co-founder Kenney (as depicted in "A Futile and Stupid Gesture") that translated into a continued loyalty with the company; long after Kenney's death, Chase kept appearing in films with the "National Lampoon" moniker, his last being "Vegas Vacation" in 1997.

Christopher Lloyd was also a loyal steward to the Lampoon, appearing in "Joy of Sex" and "Movie Madness"; Randy Quaid, already an established actor and Oscar nominee for 1973's "The Last Detail," stretched himself with a breakout comedy role in "Vacation," and the Cousin Eddie character would prove to be his most enduring, even getting his own 2003 spinoff.

Improvisation

Names like Christopher Guest, Chevy Chase, Bill Murray and Harold Ramis would come to define much of what American audiences consider the great comedies of the next several decades — and one thing they had in common was that they honed their improvisational techniques working on Lampoon projects like "Lemmings."

Decades later, many classic movie moments were the result of such training. In the "Animal House" cafeteria scene, when Belushi spits out his food and says "I'm a zit, get it?", he made it up on the spot; "Fletch," a non-"Lampoon" classic, was largely powered by Chase's off-the-cuff spontaneity. So were some of Bill Murray's best lines in "Tootsie" and, well, pretty much every other Bill Murray film.

The "Lampoon" films really gave these comedy greats full liberties to improv at will. Take, for instance, when the Griswold family has stopped for lunch at a rest stop in the original "Vacation," all digging into sandwiches that are conspicuously wet. As Ellen (Beverly D'Angelo) realizes Aunt Edna's (Imogene Coca) dog Dinky urinated on the picnic basket, Clark (Chase) notices the elusive girl in a red Ferrari (Christie Brinkley) off in the distance. The dance Clark does with his sandwich was completely improvised by Chase.

Then there's "Christmas Vacation," where Clark's famous meltdown about his boss (Brian Doyle-Murray, Bill's brother and similarly an early "Lampoon" favorite), was mostly ad-libbed — even if Chase's co-stars were wearing cue card-like signs to offer helpful suggestions for the 23 different adjectives ultimately woven together to describe him. When police invade the Griswold house and tell everyone to freeze, Beverly D'Angelo famously rests her hand on Chase's crotch; D'Angelo was more classically trained than her "Lampoon" co-stars, but the open-minded nature of such sets enabled such a moment of inspiration.

Influence from National Lampoon Magazine

Before National Lampoon became a Hollywood heavyweight in the 1980s, it was a successful humor magazine operating out of New York City. Co-founded by Kenney and Beard, its influence would include movies, radio shows, theater productions, and a bevy of books.

Kenney not only penned "Animal House," but also "Caddyshack" two years later. Comedic progenitors like Anne Beatts, Hughes, and Michael O'Donoghue all stood out in those early days.

Co-written with Ramis and Chris Miller, Kenny's "Animal House" script was inspired by college fraternity stories the Lampoon had previously published; the specific plot of the film took beats from Ramis' experience in the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity at Washington University in St. Louis, Miller's in Alpha Delta Phi at Dartmouth, and producer Ivan Reitman's time at McMaster University. Five years later, "Vacation" would arise from the stems of Hughes' "Vacation 58" story.

Actors in Their First Feature Film

Although the "Animal House" cast would become household names, it was primarily composed of, at the time, unknown faces beyond Belushi (on "Saturday Night Live" at the time) and Donald Sutherland (a veteran actor in such films as "The Dirty Dozen"). Tim Matheson (Otter) voiced the main character in the original "Jonny Quest" series.

Other cast members, especially future Academy Award-nominee Tom Hulce and Michael Mann favorite Bruce McGill, had only appeared in a few, unknown titles. Kevin Bacon and Karen Allen, far from the household names they would become, made their feature film debuts in "Animal House."

Five years later, in "Vacation," then-unknown Anthony Michael Hall would play his first high-billed movie role as Rusty Griswold. A year later, he'd become an integral part of Hughes' 1980s stable, appearing in "Sixteen Candles," "The Breakfast Club," and "Weird Science" in a 15-month span. Future "30 Rock" Emmy nominee Jane Krakowski made her film debut in "Vacation" as Eddie's daughter Vicki, delivering the immortal "Daddy says I'm the best at it" line. "Christmas Vacation" gave "Big Bang Theory" star Johnny Galecki and "Yellowjackets" actress Juliette Lewis key early roles, along with Julia Louis-Dreyfus, who'd had an underwhelming run on "SNL" and was just starting "Seinfeld."

Great Soundtracks

Alongside their classic moments of comedic genius, National Lampoon movies often contained memorable soundtracks.

"Animal House," in particular, featured historical, all-time songs that have long been pillars of party music. Ranging from Sam Cooke to the Kingsmen, the Chris Montez classic "Let's Dance" to Percy Faith's "Theme from A Summer Place," if any movie fan hears them it's hard not to flashback to key scenes, like Bluto's dining hall food fight.

Meanwhile, for "Vacation," Fleetwood Mac star Lindsey Buckingham penned his Billboard-charting song "Holiday Road" specifically for the film. "Blitzkrieg Bop" by the Ramones and "Mister Blue" by the Fleetwoods also make appearances.

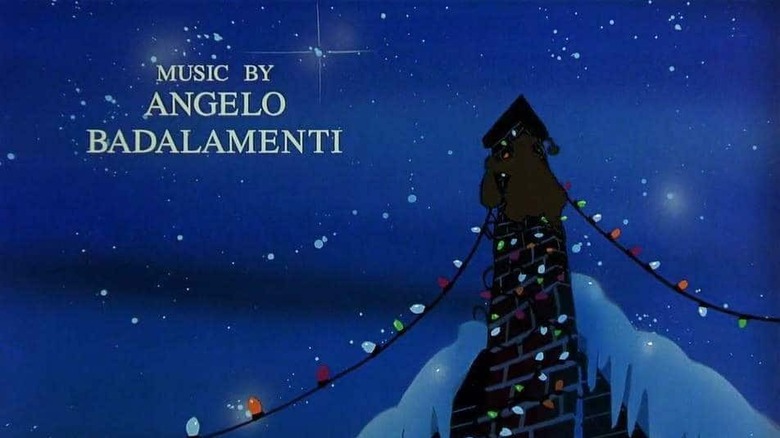

While far less iconic, "Class Reunion" featured Chuck Berry in a cameo singing "My Dingaling," and "Movie Madness" contained tunes from Dr. John and Don McLean. Plastic Bertrand's "Ça plane pour moi" would make an appearance in "European Vacation," while Mavis Staples would sing the title sequence theme song in "Christmas Vacation," which also featured Bing Crosby's "Mele Kalikimaka" and Ray Charles' "That Spirit of Christmas."

Iconic Cars

Hollywood loves iconic cars ("Smokey and the Bandit," "Back to the Future," "Ghostbusters"), and so did '80s Lampoon films.

In "Animal House," Flounder finds himself in possession of his brother's black 1964 Lincoln Continental for the weekend. During a wild night out, the Lincoln Continental is damaged; it gains a second life, however, when the Delta fraternity modifies it into the "Deathmobile," using it to wreak havoc on the homecoming parade.

"Vacation" had the "Griswold family truckster," purchased from a slimy car salesman (Levy) before their cross-country trip to California. The hideous, wood-paneled station wagon would go on to become iconic to the point where in 2022 people are still putting inflatables of it on their front lawn. Of course, Clark Griswold originally wanted a sportster, but was left with the oversized station wagon after the car dealership hauled away his trade-in and crushed it. The "family truckster" would go through the ringer, getting vandalized in St. Louis, then crashed in Monument Valley.

Saturday Night Live Alumni

1980's stand-up, improv troupes, and sketch comedy groups often overlapped. Before "Saturday Night Live" would absorb standout members of groups like The Groundlings in Los Angeles or The Second City in Chicago, it poached alumni from National Lampoon, many of whom would return for Lampoon films.

Before they were "not ready for primetime," Belushi, Chase, Gilda Radner, Bill and Brian Doyle-Murray, and Christopher Guest were regulars on the National Lampoon Radio Hour, created by humorist Michael O'Donoghue in 1973, which would run for a year. The program broadcasted nationally, reaching as many as 600 different radio stations. O'Donoghue would become the first head writer of "Saturday Night Live," and take Chase and Belushi (and later Murray) with him.

Belushi, Chase, and Doyle-Murray would go on to become integral parts of National Lampoon's film legacy, as well as other "SNL" players like Julia Louis-Dreyfus and Randy Quaid. Before NBC and "SNL" showrunner Lorne Michaels built a comedy mecca, the foundations were first forged in the National Lampoon offices, 15 minutes north in upper Manhattan. That influence would carry over into their film legacy, as Belushi and Chase, in particular, were instrumental in the company's cinema successes.

Rick Meyerowitz's Artwork

Known for his distinct, "New Yorker" cartoon-style, Rick Meyerowitz's artwork is all over the history of National Lampoon. In his early career, after graduating from Boston University, Meyerowitz was a frequent contributor to National Lampoon Magazine. His most memorable piece might be the "Mona Gorilla," a depiction of Mona Lisa as a gorilla, which graced the magazine's cover in March 1971.

While still contributing to the magazine Meyerowitz provided the poster artwork for "Animal House," a now-iconic image that depicts the Delta House, its pledges and fraternity brothers. Meyerowitz had a knack for making art that created a zany glimpse at the central themes of the film.

Four years later, Meyerowitz would go on to do the artwork for "Movie Madness," further solidifying his imprint on the Lampoon. In 2010, he put together a book, "Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Writers and Artists Who Made the National Lampoon Insanely Great," which features the work of founders Doug Kenney and Henry Beard, writers and editors Michael O'Donoghue and P.J. O'Rourke, and artists Meyerowitz, Michael Gross, and Bruce McCall, among countless others.

John Hughes' Scripts

Hughes began his career at National Lampoon Magazine in 1970, penning humor essays and short stories. After dropping out of the University of Arizona, he wrote jokes for Rodney Dangerfield and Joan Rivers before becoming a copywriter for Needham, Harper & Steers and later Leo Burnett Worldwide in Chicago. But once he got to the Lampoon, he impressed his editors with his work ethic, turning around stories in record time.

After "Vacation 58" became "Vacation" and his script for "Mr. Mom" became a sizable hit that same year, Hughes landed a three-film deal with Universal Pictures. Those films would become "Sixteen Candles," "The Breakfast Club," and "Weird Science" — not a bad return on investment. Hughes would go on to write the scripts for "Class Reunion" and "European Vacation," but found his greatest fame as a writer/director and producer on such classics as "Ferris Bueller's Day Off," "Planes, Trains and Automobiles" and "Home Alone."

Revenge Plots

Lampoon was heavy on revenge plots in their first wave of movies. After the Delta fraternity in "Animal House" is dissolved by Faber College, the remaining Deltas band together to enact revenge on the university at its annual homecoming parade; in "Class Reunion," the Lizzie Borden High class of 1972 features a psychotic alumni who escapes from a mental institution and begins killing his former classmates.

The most memorable Lampoon revenge plots, however, come in "Vacation" and "Christmas Vacation." In the former, after learning Walley World is closed, family patriarch Clark Griswold takes John Candy's security guard hostage and makes him go on the rides with the family. In "Christmas Vacation," well-intentioned Cousin Eddie (Randy Quaid) takes an off-the-cuff remark from Clark seriously and kidnaps his boss. While such revenge plots can be commonplace in comedies ("Horrible Bosses," "Swimming With Sharks"), Lampoon films did it with a unique mix of humor, heart and cruelty that still stands out.

Famous Score Composers

Sure, Lampoon wasn't using John Williams, John Barry, or Ennio Morricone — but when it came time to score their comedies, they did just fine.

"Animal House" brought in Oscar-winner Elmer Bernstein, famous for arranging the scores of "To Kill a Mockingbird," "The Great Escape," "True Grit," and "Cape Fear." Tasked with soundtracking the debauchery of the Delta fraternity, he delivered a whimsical, everlasting score that paralleled the goofy heart living deep within the movie.

Bernstein's son Elmer scored "Class Reunion," and saxophonist (and member of Garrison Keillor's "A Prairie Home Companion") Andy Stein scored "Movie Madness." But it was Ralph Burns, composer of "Vacation," that set a precedent in comedy scores. Burns, who attended the New England Conservatory of Music during World War II, was influenced by the works of Count Basie and Duke Ellington. He orchestrated numerous Broadway shows, including "Chicago" and "Funny Girl," but his film scores for "Cabaret" and "All That Jazz" would earn him Academy Awards. For "European Vacation," the Lampoon crew brought in "Wide World of Sports" composer Charles Fox.

Perhaps the most famous composer in a Lampoon movie, however, is Angelo Badalamenti. Just a year before providing the iconic sounds for "Twin Peaks," he scored "Christmas Vacation." Badalementi would go on to develop a long, fruitful collaborative friendship with filmmaker David Lynch, working together on such projects as "Lost Highway," best picture nominee "Mulholland Drive" and 2017's audacious "Twin Peaks: The Return."

Oscar Nominees

Though National Lampoon movies were not often serious, some actors who starred in the company's productions went on to receive Oscar nominations.

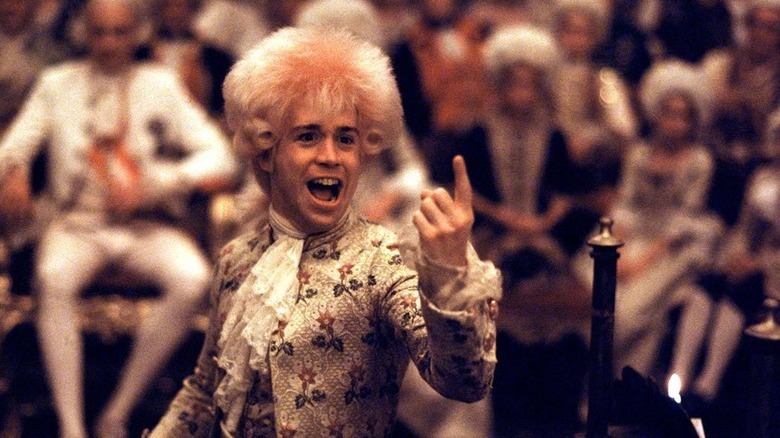

In "Animal House," a then-unknown Tom Hulce was cast as the naive-yet-lovable Pinto. Six years later, Hulce would go on to star in his most-memorable role, as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Milos Forman's Best Picture Oscar-winning "Amadeus." Hulce earned Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for his work, but lost out on both to his co-star, F. Murray Abraham. In "Class Reunion," Michael Lerner played a memorable leading role, but he wouldn't find the acclaim he deserved until 1991, when he'd earn a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination for his work in the Coen Brothers' "Barton Fink."

In "Movie Madness," the worst film of the Lampoon's original company run, a then-unknown, 17-year-old Diane Lane played a key role in the movie's first chapter, "Growing Yourself." Lane would eventually earn an Oscar nomination for her part in Adrian Lyne's 2002 film "Unfaithful." Though the Lampoon was never a hotbed for dramatic turns, it produced a bevy of actors who'd deliver important performances in Hollywood for decades to come.

Director/Writer Cameos

While even eagle-eyed viewers might not realize it, the early Lampoon films had a thing for sly writer/director cameos.

In "Animal House," writer/producer/Lampoon founder Kenney plays Stork, a member of the Delta fraternity. Stork's claim to fame is he is the character that marched the Faber marching band straight into a brick wall during the homecoming parade. Kenney only has a few lines, but all these decades later, it's nice to see a genuine comic genius immortalized in the film.

"Vacation," meanwhile, features director Ramis in a small, off-screen cameo, voicing one of the police officers at Walley World. He also provides the voice of Walley World mascot Marty the Moose. In "Class Reunion," writer Hughes has an uncredited role as the "girl with a bag on head." Lastly, in one of the more clever director cameos of the era, "Christmas Vacation" features a memorable scene where Clark is navigating a copy of People Magazine with sticky, sap-riddled fingers. The man on the cover of the issue? The film's director, Jeremiah S. Chechik.