Cinematographer Matty Libatique Takes Us Behind The Scenes Of Don't Worry Darling - Exclusive Interview

This article contains mild spoilers for "Don't Worry Darling."

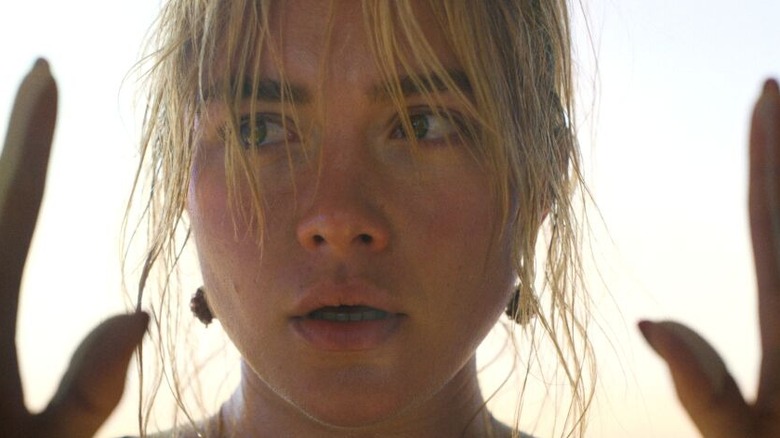

Olivia Wilde's newest film "Don't Worry Darling" is finally in theaters following its Venice premiere. The series stars Marvel A-lister Florence Pugh and songster Harry Styles as Alice and Jack, a happily married couple living in Victory. Jack and the other men of the neighborhood spend their days heading off to work on a mysterious government project, while Alice and the other wives spend time keeping home, raising kids, and keeping husbands happy in a technicolor 1950s wonderland. Everything goes smoothly until Alice begins to notice an escalating set of issues in Victory. Surprise, surprise — no one wants questions in this neighborhood.

Centered around Pugh's stunning performance with a complex mystery at its heart, "Don't Worry Darling" is also a gorgeously shot spectacle thanks to the beautiful camera work of Director of Photography Matty Libatique. We spoke to the famed cinematographer about collaborating with director Olivia Wilde, the use of dance and geometric imagery to tell the story, the film's influences, Harry Styles' ecstatic dancing, and more.

Signing up for a 1950s Palm Springs sci-fi spectacle

How did you come to be involved with "Don't Worry Darling," and how it was different to shoot from your first collaboration with Olivia Wilde on the short film "Wake Up"?

It wasn't that different in terms of the collaboration with her as a director. It's so easy for her. She's effortless in the way she could explain what she's after, and the atmosphere of it. It happened on the short we worked together on, and it happened on this film. Obviously, the film "Don't Worry Darling" was on a bigger scale so there was a little more to be concerned with, but the general core of it was an easygoing collaboration.

As we were shooting "Wake Up," she mentioned this film, but she was pretty vague about it. She said, "It's a science fiction film set in the 1950s about Palm Springs." Well, that sounds intriguing, but I was already on something ... and then the shutdown happened.

I didn't know this, but she was meant to shoot in June. It was the early summer of that year, in 2020. They had to push. I was on something else, so I couldn't even do the film, and then she called me sometime in late August or early September and said that she was rebooting and [asked if] I would consider coming on, even though she had prepped the movie.

I didn't ask too many questions about why or what had happened. I think she reconsidered the entire film and she was going into a recasting, and I was part of it. I ended up saying yes because I loved working with her, and I was intrigued by it. When she mentioned it before, I couldn't do it.

She pitched it on the phone — I was driving. I pulled over and wanted to hear more. She's mentioning things like the Rat Pack, this idyllic world, and the debauchery and the beauty and the sex, and I was like, "Okay, that sounds like something I would love to do."

I met her in person, and we started to chat about the images that were posted behind her on a wall in her office. Slowly but surely, I was getting more and more details [about] her vision about the film. It started there, and because I came in so late, the palette had already been set, the design was set. That first week of prep, I had to hit the ground running and get as much information from her as possible, and then amplify that with more information from her collaborators.

Wilde loves cinematic imperfections and happy accidents

Directors and cinematographers always have different styles of collaboration. What was it like working with her on this project?

It was very similar to "Wake Up" where it was ... For lack of a better term, it felt free, and things were predetermined in a sense — not in the shot list, but what the aims of each scene were. She knew she had to convey her intention to me because in many cases, she'd be in the scene. The challenge was in going in knowing that she'd be spending some time in the chair at the beginning of the day and I wouldn't have access to her, which meant that we'd have to prepare ahead of time in terms of what our coverage scheme would be. Whether it be an exterior with her and with Bunny and Alice on the outside of their house, or if it was a giant scene inside the Victory celebration where everybody was there, she sets the tone. [It was about] picking up on what she wants and the atmosphere of it.

She's so easy to be around and so good at conveying the atmosphere she's trying to create that I didn't have to communicate it singularly to each and every person, because everybody wants to be around to hear it. You have all our collaborators, and you have my crew that's listening in to her, and we can get off and running and set it up. Myself and the AD had to have a pretty tight relationship about what Olivia wanted to do, because we didn't have access to her at the beginning of the day, where she was in the scene. That was logistical, most of all.

But she loves happy accidents, and she loves the imperfections that became cinematic, so putting ourselves in a position to exploit those things was as important as getting the shots that told the scene in a very basic way. She loves to move the camera and keep the actors moving. We knew that, so [we worked] on blocking and shots and timing, and she was on the field with the other actors so she could create timing. A good example of that is at the Kaufmann House, where we're having Frank's backyard party that he's throwing and we're meeting Bill and Violet for the first time.

The cameras are flowing through this conversation and picking up bits of this conversation and little nuances like Bill being reprimanded by Nick Kroll's character, but then also, [we're] seeing Alice notice that. It's a bunch of actors who can see the camera in their peripheral vision and would time everything out to us. It was interesting having somebody who could help with that cadence and that connection between camera and performance. She cast each and every person because of their ability to bounce off and play this jazz-like orchestra of performance.

Creating the energy was harder than it looked

I loved the utilization of dance in this film. There's a lot of ballet; there's Busby Berkeley-type dance motions ... I know with "Black Swan," for example, you've had ample opportunities to shoot ballet before, but what differentiates how you approached this project versus others like "Black Swan"?

Everything's different. I wasn't as focused on the dance on this because ... The difference is the dances were attached to the theme of femininity within the ballet here. They're attached to a metaphor, but also a narrative vehicle in the Busby Berkeley material, so it was a part of a larger picture. I approached it from a standpoint of, "How do I help create this world that's already idyllic and beautiful?"

Within the performance and the writing, Olivia [Wilde], as a filmmaker, was setting it on its side, making it more like the Rat Pack, the world of Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr. From a photographic standpoint, I was trying to set it on its side a little bit by using lenses and optics that would have been a little more of an aberration amidst this beauty and perfection. That was more my concern — the overall atmosphere — because when she first talked about the film to me, it was very important that the place that we were in is believable. In the first few scenes, this is a movie about this awesome place, and we don't know where we're going to go from there.

Harry Styles exhausted himself doing the barrel rolls

I also loved that meeting where Harry Styles' character gets a promotion, and then Florence Pugh leaves, and he's dancing on stage in an increasingly feverish crescendo. It's almost fascistic. It's a lot of things. What was it like to shoot that scene, and what considerations went into it?

It was really tough for that scene because the energy that you feel was compiled through sound and editorial, because [it was] in the time of COVID. Typically, we'd have an entire crowd of people — we'd move them so the energy would be embedded in the shooting, but because of COVID, we had to clear it. If we were looking at the stage and we were cleaning up, we'd have to clear them out because of COVID safety, so that was harder than it looked in terms of creating that energy.

I have to give Chris Pine so much credit because he was working off of an empty house. What was great about it was that we tried to shoot, and we had this shot that's behind that action that sees the crowd. We tried to do that to set the tone. Then, when we got into the tighter coverage, the tone was already set, so it helped the performance or gave them at least the tools to be able to go there.

Going into it from a photographic standpoint, it was strategic in the sense that we did have to be [like], "How do we tell this story that this Victory world has a lot of people in it?" We show the model, and you see the environment of the model that we boom up on, and we see Alice looking at the party at Frank's house, but then we're at Victory. This is the grand celebration!

You're right — it's very fascistic ... It's a sea in the sense of the amount of people that were sitting there listening to their oracle. We had to be clever and construct our shots and get the wides done with 1) limited people and 2) in an amount of time that was COVID safe, [then] get them out, and then get them the core of the scene in clean coverage. We were bound by our restrictions — which, any movie is bound by its restrictions.

We had the camera on a remote head and a jib arm when Harry [or] "Jack" was doing the barrel rolls and dancing, because it starts slow. He's dancing, but once he starts going to the barrel rolls, we needed the freedom to back up and make sure we saw just enough to sell what he was doing. He was actually doing those things! We didn't want to shortchange it, but it was so beautiful. We wanted to see it from multiple angles. He was exhausted.

I'm glad it was really him because I was like, "If this is movie magic ..."

I said, "Did you practice those?" The rest of us were looking at it on YouTube: "How do you do a barrel roll?" But this poor guy in those shoes — I was like, "This is crazy."

A 'world created by men' with a feminine story at its core

I'm also interested in the many instances of geometric and circular imagery: irises, dancers, cul-de-sacs, coffee mugs ... What was the decision process to come to those motifs and that imagery?

That's all born out of Olivia [Wilde]. When I first met her and I saw the wall of inspiration, there was one striking image of an eyeball that she was so attached to, and it felt like she was carrying it around in her mind all the time. It was a theme, and [in] everything she was doing, she wanted the repeatability and consistency of that shape.

It's a world created by men, and within it, there's a feminine story, so the circle was this shape inside a square or a rectangle. The architecture of mid-century modern [is] straight lines, but then you always go back in the circle. I kept thinking that that was her — she was drawn to it, even the coffee cup. There's a shot of a coffee cup where it's endless coffee going in at the end of the film, [and] still you get left with that circle.

It's a very clever vehicle, reminding the audience what the point of the story is in a very subtle way. That's what I love about working with her — her ideas come from ... not just a narrative sense, where we are bound in cinema to be more literal in our storytelling. She likes to intersperse the poetry and the art of it into the films. I think that's why "Booksmart" was so successful, and why this one works as an entertaining ride is because she's able to incorporate those ideas and her intellect inside a told story.

"Don't Worry Darling" is now playing in theaters.

This interview has been edited for clarity.