The Ending Of Mike Explained

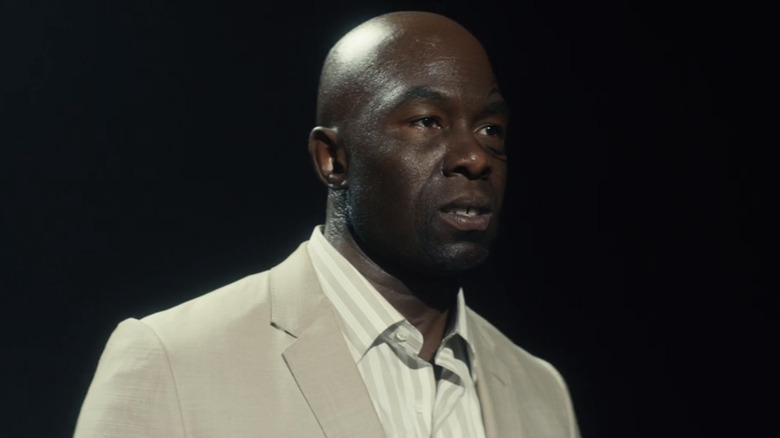

The Hulu miniseries "Mike" ends as it begins, with former heavyweight boxing champion Mike Tyson (Trevante Rhodes) on stage in a crowded theatre, pondering what exactly he is, and what his story means in the grand scheme of American life. Born into poverty and violence, Tyson's phenomenal boxing skills were discovered while he was serving time in an upstate New York juvenile detention center. Trained in his early years by the legendary Cus D'Amato (Harvey Keitel), Tyson became the youngest heavyweight champion in history when he defeated Trevor Berbick in 1986 at age 20.

Over the decades Tyson has been seen as pretty much everything, often all at once: A hero, a pariah, a sex offender, a sideshow attraction, an addict, a criminal. His life is arguably too large for even a four-hour miniseries, and creators Steven Rogers and Craig Gillespie ("I, Tonya") take a Wikipedia-style approach, hitting relevant details via near-constant narration before moving on to the next big event. The final episode moves through the last two decades of Tyson's life at a breakneck pace, barely stopping for major events like the death of his daughter in 2009, on the way to answering the question posed at the very beginning: Just who is Mike Tyson, really? This approach loses a lot of crucial context and leaves some moments frustratingly unclear. Let's take a look at some of the real-life details that help explain the ending of "Mike."

Fraught beginnings

Tyson's life story has been told onscreen before, most notably in the 1995 HBO biopic "Tyson" starring Michael Jai White. Actor Jamie Foxx, who used to parody Tyson on "In Living Color," has been trying to get a biopic of his own off the ground for years. But when Hulu announced in early 2021 that it was moving forward with an unauthorized Tyson miniseries from Rogers, Gillespie, and Margot Robbie, the braintrust behind the 2017 Tonya Harding biopic "I, Tonya," it was met with angry protests — mostly from Tyson himself, who accused Hulu of "cultural appropriation" in a statement to Entertainment Tonight.

As the series approached its premiere in August 2022, Tyson took to social media to express his displeasure with some harsh language, accusing Hulu not just appropriation, but of literal slave trading. He also praised friends of his, like UFC owner Dana White, for not helping to promote the series. In their defense, Rogers and showrunner Karen Gist explained to the Television Critics Association (via Entertainment Tonight) that their unauthorized version of the story was a legal necessity, as the rights to Tyson's life were tied up with other parties; they couldn't have consulted or paid Tyson even if they wanted to. "We just wanted to tell an unbiased story and have the audience decide what they think or feel," Gist explained during Hulu's TCA presentation.

Undisputed truth

So in the end, does "Mike" provide an unbiased view of its subject? It's difficult to say, as the series is told almost entirely from Tyson's own perspective and in his own words. Rogers and company lean heavily on Tyson's 2013 memoir "Undisputed Truth" and the accompanying one-man show that Tyson performed in Vegas, Broadway, and on HBO. The miniseries uses a fictionalized version of that show as its framing device, as Tyson performs his life story for a rapt audience, and seems to have taken a number of specific details, especially in its early episodes, from the memoir; a scene in Episode 2 in which trainer Teddy Atlas accuses a teenage Mike of stealing appears to have been adapted directly from this excerpt reprinted in New York magazine.

Elsewhere, the series mitigates the allegations of abuse in his eight-month marriage to actress Robin Givens (Laura Harring) by focusing on his dubious manic depression diagnosis and the lithium prescription that was forced upon him (in the show's telling) by Givens and her mother. In Episode 5, "Desiree," the story of Tyson's 1992 sexual assault conviction is told through the perspective of his victim Desiree Washington (Li Eubanks), which is meant to be respectful to her experience but has the unintended consequence of distancing Tyson from the facts of his own crime. By the final episode, the series takes his claims of healing and sobriety with the support of his third wife Kiki at face value. Tyson's anger at Hulu hijacking his life is understandable, but at the end of it all, he could hardly have wished for a more supportive telling.

The Bite Fight

The final episode begins in the aftermath of Tyson's infamous 1997 rematch with Evander Holyfield, better known as "the Bite Fight." After Tyson lost his first match with Holyfield in 1996, he and his team complained that he had been on the receiving end of several intentional head-butts. When Tyson was once again head-butted toward the beginning of the rematch, he retaliated by biting Holyfield's right ear so hard he severed a piece of cartilage and shoved Holyfield to the canvas. Referee and future TV judge Mills Lane called a timeout and deducted two points from Tyson. When the action resumed, Tyson bit Holyfield's left ear, at which point Mills disqualified Tyson.

Tyson's actions in the ring were a massive public scandal, arguably bigger than the Desiree Washington case five years earlier. To emphasize exactly what a big deal it was, the series switches tactics in depicting the public's reaction. Where previous episodes used meticulous recreations of Tyson's interviews with Joan Rivers, Barbara Walters, and others, Episode 8 opens with vintage television clips, as Ann Curry reports on Tyson's suspended boxing license for "The Today Show" and David Letterman cracks jokes during a "Late Show" monologue. Even president Bill Clinton weighs in on the incident, stating that he was "horrified" by it. The interview with Desiree Washington, however, in which she laments the media's attention to the violence against Holyfield when they had ignored the violence against her, appears to be an invention of the show; Washington has never spoken publicly about her assault since her interview with Barbara Walters in 1992.

The bite press conference

Much of Tyson's life is truly stranger than fiction, and it's to the series' credit that they often present his wildest moments more or less as they actually happened. The first fight of his life really was against a bully who had decapitated one of his pet birds. He really did crash his BMW into a tree in what many at the time believed to be a suicide attempt. And he really did bite Lennox Lewis in the leg during a melee that broke out in the middle of a press conference for their 2002 fight in Memphis.

After Tyson's 15-month suspension for the Bite Fight ended, he returned to the ring with a vengeance, notching six fights from early 1999 to late 2001. The spring 2002 fight against IBF, IBO, and WBC heavyweight champ Lewis was his first chance at a title since fighting Holyfield. As the press conference began, Tyson stood on stage alone, dressed all in black. When Lewis entered from the other side of the stage, Tyson advanced on him and immediately started throwing punches. Soon the stage was filled with members of the two men's teams, and as Lewis attempted to crawl out of the ruckus, Tyson grabbed him by the leg and bit his calf. The incident cost Tyson over $300,000 in fines and put the fight — the biggest in history up to that point — in doubt. In the end, the fight continued and Lewis knocked Tyson out in the 8th round to retain his championship belts. It would be the last time Tyson was ever in contention.

Tyson and the King

The final episode brings to a close Tyson's complicated, combative relationship with boxing promoter Don King (Russell Hornsby). The final collapse of their relationship occurs in 2003, when King picks up Tyson and a friend from the Miami airport, only to have an inebriated Tyson attack him while driving. What's amazing about the scene is that not only is it based on a real-life incident, but that the real-life version was even wilder than the show depicts. On a 2020 episode of his podcast "Hotboxin' with Mike Tyson," he tells fight announcer Jim Gray the whole story: Not only did he attack King and his driver, but after chasing King around the car and getting left on the side of the road, he punched out another member of King's detail who was driving behind them.

But Tyson's battles with King were not just on the highway. In 1998, he sued his former manager for $100 million he claimed had been stolen over the years. The series doesn't get into their courtroom battles, other than a quick scene in the finale when Tyson barks "Where's my f***ing money?" at his lawyer, who can only offer a sheepish "Ask Don King" in response. The lawsuit stretched on for six years and wouldn't be settled until 2004, the year after their automobile altercation. The final number awarded to Tyson was just $14 million, all of which went to paying off his various creditors and his ex-wife Monica Turner (played in the series by Clark Backo).

The final fight

By the time King and Tyson settled in 2004, Tyson was still seriously in debt, but his professional boxing career was about to come to a close. After losing to Lennox Lewis, Tyson scored an easy first-round knockout of Clifford Etienne in 2003, but back-to-back losses to Danny Williams and Kevin McBride in 2004 and 2005 put him on the canvas for good. The series shows us the final moments of his fight with McBride as Tyson, now sporting his famous face tattoo, slumps against the ropes, exhausted and unwilling to go on. The scene then cuts to the post-fight interview in which he regretfully announces his retirement.

All of what is shown is true to the real fight and its aftermath, but like Tyson and King in the car, the series leaves out the fight's most outrageous moments. In some ways it was as bad a night for Tyson as the Bite Fight, with the one-time champ intentionally head-butting McBride and attempting to break his arm just as he had in his foul-laden 1999 match with Francois Botha. McBride would later claim that Tyson had tried to bite his nipple off at one point. At the end of Round 6 after falling from a push by McBride, Tyson quit in his corner, refusing to come out for Round 7. The baddest man on the planet had finally reached his limit.

Kiki

Tyson's divorce from Monica Turner, whom he married in 1997 just months before his rematch with Holyfield, happens offscreen. When the episode picks back up with his domestic life, it's after the McBride fight and Tyson is living with a woman named Kiki Spicer (Ash Santos). Tyson has said that his union with Spicer, which began when he met her as an 18-year-old in 1995, was "a lifesaving experience" (per the New York Post). Spicer would go on to co-write the "Undisputed Truth" stage show, but before that, she served six months in jail for fraud in 2009 while pregnant with Tyson's daughter Milan.

The show is more interested in the image of a visibly pregnant Spicer sitting in a jail cell — which is a bit of dramatic license, as Spicer had just found out she was pregnant a week before her sentence began — than fleshing out the details of why she was incarcerated. From 1999 to 2001 she was involved in a scheme with her mother Faridah Ali, brother Osh Spicer, and others to defraud the government as faculty members of the Sister Clara Muhammad School in Philadelphia, pocketing money earmarked for adult education classes that never actually happened. After her sentence was complete, she came home to find Tyson apparently deep into a drug addiction; he credits her with getting him through the toughest moments in his life at that time.

Therapy session

Tyson has long had a troubled relationship with parental figures, both real and surrogate. The miniseries gets much of its drama in its early episodes from contrasting his bitter, alcoholic mother Lorna (Canadian actor Olunike Adeliyi, giving arguably the series' best performance) with the warm encouragement of surrogate father Cus D'Amato. But no one is all saint or all demon, and it takes a session in the final episode with another surrogate parent, therapist Marylin Murray (Patricia Bethune), to make Tyson see that.

In real life Tyson began seeing Murray, who specializes in trauma recovery, after being released from prison in 1995, but the series saves her for a key moment in the final episode in which she lays out his issues with his parental figures in a perhaps too-tidy way, noting that despite his professed hatred for his mother, he still had her body exhumed and moved to a new burial plot — essentially moving her to a nicer house once he became rich and famous. And even though Cus treated him like a son, he instilled many of Tyson's most negative qualities — his fearsomeness, his violence, his dependency. It's a moment of clarity, if for no one else but the audience; Tyson isn't quite ready to accept the truth.

Exodus Tyson

In the finale's mad dash to the finish line, less than a minute of screen time is spared for the 2009 death of Tyson's daughter Exodus. Exodus and her brother Miguel were the children of Tyson and his ex-girlfriend Sol Xochitl, briefly played in the series by Andrea Andrade. Exodus was playing alone at her home in Phoenix, Arizona when she accidentally got tangled up in the cord from Xochitl's treadmill. Miguel found her unconscious and alerted their mother, who called 911 and administered CPR until the paramedics arrived. Exodus was admitted to the ICU but died the next day. Tyson, who was in Las Vegas at the time, flew to Phoenix immediately after being informed of the accident, but unfortunately arrived at the hospital after his daughter's death.

Tyson, as he revealed in a 2013 interview on HBO's "Real Sports," was left in a mindless rage by the death of his daughter: "This is my best thinking at the time: Get my gun ... and just go crazy." When asked who he would have attacked in this line of thinking, he just shook his head: "Regardless. That's just my first thought." Tyson spiraled into a heavy cocaine binge, which the series dramatizes with a shot of him on the floor with lines of cocaine on a tray nearby, but out of that pain came a new dedication to his remaining family. He and Spicer were married a week after Exodus' death.

Me, I'm the American dream

So after four hours and eight episodes, has "Mike" achieved Gist's stated goal of telling "an unbiased story" about one of the most famous athletes of the 20th century? Perhaps more importantly, does "Mike" offer any further insight than the scores of books and magazine articles that have been written about Tyson over the years, the interviews and documentary features he has taken part in, the one-man show that he co-wrote and performed across the country, or even his Wikipedia page? The final episodes move so fast that they seem like a stylish reading of facts with the occasional bloody ear flying through the air, but the early episodes make an earnest attempt to depict Tyson's upbringing and the forces that shaped him into the man he is.

The finale ends with a montage of moments and characters from earlier in the series — his mother, Cus D'Amato, Robin Givens, and Desiree Washington — set to the insistent beat of Nina Simone's "Sinnerman." "Me, I'm the American dream, red state and blue," Tyson narrates. "The good and the bad, just like you." In the real "Undisputed Truth," Tyson's summary is less grandiose, focusing not on what he means as a symbol, but what it means for him to stand in front of an audience and bear his soul, "naked as I came into the world." He sounds grateful to be standing on a Broadway stage when he just as likely could have been shot dead in Brooklyn as a teen, just a few miles away. It's a simple insight, but one that "Mike" ultimately can't grasp, aside from Trevante Rhodes' transformative performance.